Stage-coach and Tavern Days

The bill is endorsed with unconscious humor, “This all paid for except the Ministers Rum.”

The book already referred to, called Notions of the Americans, tells of taverns during the triumphal tour of Lafayette in 1824. The author writes thus of the stage-house, or tavern, on the regular stage line. He said he stopped at fifty such, some not quite so good and some better than the one he chooses to describe, namely, Bispham’s at Trenton, New Jersey.

“We were received by the landlord with perfect civility, but without the slightest shade of obsequiousness. The deportment of the innkeeper was manly, courteous, and even kind; but there was that in his air which sufficiently proved that both parties were expected to manifest the same qualities. We were asked if we all formed one party, or whether the gentlemen who alighted from stage number one wished to be by themselves. We were shown into a neat well-furnished little parlour, where our supper made its appearance in the course of twenty minutes. The table contained many little delicacies, such as game, oysters, and choice fish, and several things were named to us as at hand if needed. The tea was excellent, the coffee as usual indifferent enough. The papers of New York and Philadelphia were brought at our request, and we sat with our two candles before a cheerful fire reading them as long as we pleased. Our bed-chambers were spacious, well-furnished, and as neat as possible; the beds as good as one usually finds them out of France. Now for these accommodations, which were just as good with one solitary exception (sanitary) as you would meet in the better order of English provincial inns, and much better in the quality and abundance of the food, we paid the sum of 4s. 6d. each.”

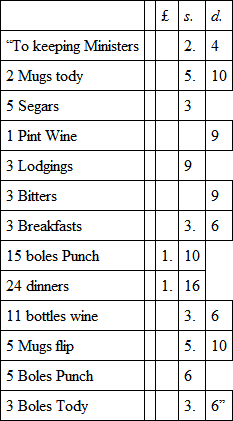

A copy is given opposite page 86 of a bill of the “O. Cromwell’s Head Tavern” of Boston, which was made from a plate engraved by Paul Revere. This tavern was kept for over half a century by members of the Brackett family. It was distinctly the tavern of the gentry, and many a distinguished guest had “board, lodging, and eating” within its walls, as well as the wine, punch, porter, and liquor named on the bill. It will be noted that the ancient measure – a pottle – is here used. Twenty years before the Revolutionary War, and just after the crushing defeat of the British general, Braddock, in what was then the West, an intelligent young Virginian named George Washington, said to be a good engineer and soldier, lodged at the Cromwell’s Head Tavern, while he conferred with Governor Shirley, the great war Governor of the day, on military affairs and projects. When this same Virginian soldier entered Boston at the head of a victorious army, he quartered his troops in Governor Shirley’s mansion and grounds.

The sign-board of this tavern bore a portrait of the Lord Protector, and it is said it was hung so low that all who passed under it had to make a necessary reverence.

While British martial law prevailed in Boston, the grim head of Cromwell became distasteful to Tories, who turned one side rather than walk under the shadow of the sign-board, and at last Landlord Brackett had to take down and hide the obnoxious symbol.

The English traveller Melish was loud in his praise of the taverns throughout New York State as early as 1806. He noted at Little Falls, then in the backwoods, and two hundred miles from New York, that on the breakfast table were “table-cloth, tea tray, tea-pots, milk-pot, bowls, cups, sugar-tongs, teaspoons, casters, plates, knives, forks, tea, sugar, cream, bread, butter, steak, eggs, cheese, potatoes, beets, salt, vinegar, pepper,” and all for twenty-five cents. He said Johnstown had but sixty houses, of which nine were taverns.

Another English traveller told of the fare in American hotels in 1807. While in Albany at “Gregory’s,” which he said was equal to many of the London hotels, he wrote: —

“It is the custom in all American taverns, from the highest to the lowest, to have a sort of public table at which the inmates of the house and travellers dine together at a certain hour. It is also frequented by many single gentlemen belonging to the town. At Gregory’s upwards of thirty sat down to dinner, though there were not more than a dozen who resided in the house. A stranger is thus soon introduced to an acquaintance with the people, and if he is travelling alone he will find at these tables some relief from the ennui of his situation. At the better sort of American taverns very excellent dinners are provided, consisting of almost everything in season. The hour is from two to three o’clock, and there are three meals in the day. They breakfast at eight o’clock upon rump steaks, fish, eggs, and a variety of cakes with tea or coffee. The last meal is at seven in the evening, and consists of as substantial fare as the breakfast, with the addition of cold fowl, ham, &c. The price of boarding at these houses is from a dollar and a half to two dollars per day. Brandy, hollands, and other spirits are allowed at dinner, but every other liquor is paid for extra. English breakfasts and teas, generally speaking, are meagre repasts compared with those of America, and as far as I observed the people live with respect to eating in a much more luxurious manner than we do. Many private families live in the same style as at these houses; and have as great variety. Formerly pies, puddings, and cyder used to grace the breakfast table, but now they are discarded from the genteeler houses, and are found only in the small taverns and farm-houses in the country.”

In spite of the vast number of inns in Philadelphia, another English gentleman bore testimony in 1823 that he deemed the city ill-provided with hostelries. This gentleman “put up” at the Mansion House, which was the splendid Bingham Mansion on Third Street. He wrote: —

“The tavern-keepers will not receive you on any other terms except boarded at so much a day or week; you cannot have your meals by yourself, or at your own hours. This custom of boarding I disliked very much. The terms are, however, very moderate, only ten dollars per week. The table is always spread with the greatest profusion and variety, even at breakfast, supper, and tea; all of which meals indeed were it not for the absence of wine and soup, might be called so many dinners.”

There lies before me a collection of twoscore old hotel bills of fare about a half century old. They are of dates when stage-coaching had reached its highest point of perfection, and the coaching tavern its glory. There were railroads, – comparatively few lines, however, – but they had not destroyed the constant use of coaches.

These hotels were the best of their kind in the country, such as the United States Hotel of Philadelphia, Foley’s National Hotel of Norfolk, Virginia, Union Place Hotel and New York Hotel of New York, Union Hotel of Richmond, Virginia, American House of Springfield, Massachusetts, Dorsey’s Exchange Hotel and Barnum’s City Hotel of Baltimore, Maryland, the Troy House, the Tremont House of Boston, Massachusetts, etc. At this time all have become hotels and houses, not a tavern nor an inn is among them.

The menus are printed on long narrow slips of poor paper, not on cardboard; often the names of many of the dishes are written in. They show much excellence and variety in quality, and abundant quantity; they are, I think, as good as hotels of similar size would offer to-day. There are more boiled meats proportionately than would be served now, and fewer desserts. Here is what the American House of Springfield had for its guests on October 2, 1851: Mock-turtle soup; boiled blue-fish with oyster sauce; boiled chickens with oyster sauce; boiled mutton with caper sauce; boiled tongue, ham, corned beef and cabbage; boiled chickens with pork; roast beef, lamb, chickens, veal, pork, and turkey; roast partridge; fricasseed chicken, oyster patties, chicken pie, boiled rice, macaroni; apple, squash, mince, custard, and peach pies; boiled custard; blanc mange, tapioca pudding, peaches, nuts, and raisins. Vegetables were not named; doubtless every autumnal vegetable was served.

At the Union Place Hotel in 1850 the vegetables were mashed potatoes, Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes, boiled rice, onions, tomatoes, squash, cauliflower, turnips, and spinach. At the United States Hotel in Philadelphia the variety was still greater, and there were twelve entrées. The Southern hotels offered nine entrées, and egg-plant appears among the vegetables. The wine lists are ample; those of 1840 might be of to-day, that is, in regard to familiar names; but the prices were different. Mumm’s champagne was two dollars and a half a quart; Ruinard and Cliquot two dollars; the best Sauterne a dollar a quart; Rudesheimer 1811, and Hockheimer, two dollars; clarets were higher priced, and Burgundies. Madeiras were many in number, and high priced; Constantia (twenty years in glass) and Diploma (forty years in wood) were six dollars a bottle. At Barnum’s Hotel there were Madeiras at ten dollars a bottle, sherries at five, hock at six; this hotel offered thirty choice Madeiras – and these dinners were served at two o’clock. Corkage was a dollar.

Certain taverns were noted for certain fare, for choice modes of cooking special delicacies. One was resorted to for boiled trout, another for planked shad. Travellers rode miles out of their way to have at a certain hostelry calves-head soup, a most elaborate and tedious dish if properly prepared, and a costly one, with its profuse wine, but as appetizing and rich as it is difficult of making. More humble taverns with simpler materials but good cooks had wonderful johnny-cakes, delightful waffles, or even specially good mush and milk. Certain localities afforded certain delicacies; salmon in one river town, and choice oysters. One landlord raised and killed his own mutton; another prided himself on ducks. Another cured his own hams. An old Dutch tavern was noted for rolliches and head-cheese.

During the eighteenth century turtle-feasts were eagerly attended – or turtle-frolics as they were called. A travelling clergyman named Burnaby wrote in 1759: —

“There are several taverns pleasantly situated upon East River, near New York, where it is common to have these turtle-feasts. These happen once or twice a week. Thirty or forty gentlemen and ladies meet and dine together, drink tea in the afternoon, fish, and amuse themselves till evening, and then return home in Italian chaises, a gentleman and lady in each chaise. On the way there is a bridge, about three miles distant from New York, which you always pass over as you return, called the Kissing Bridge, where it is part of the etiquette to salute the lady who has put herself under your protection.”

Every sea-captain who sailed to the West Indies was expected to bring home a turtle on the return voyage for a feast to his expectant friends. A turtle was deemed an elegant gift; usually a keg of limes accompanied the turtle, for lime-juice was deemed the best of all “sourings” for punch. In Newport a Guinea Coast negro named Cuffy Cockroach, the slave of Mr. Jahleel Brenton, was deemed the prince of turtle cooks. He was lent far and wide for these turtle-feasts, and was hired out at taverns.

Near Philadelphia catfish suppers were popular. Mendenhall Ferry Tavern was on the Schuylkill River about two miles below the Falls. It was opposite a ford which landed on the east side, and from which a lane ran up to the Ridge Turnpike. This lane still remains between the North and South Laurel Hill cemeteries, just above the city of Philadelphia. Previous to the Revolution the ferry was known as Garrigue’s Ferry. A cable was stretched across the stream; by it a flatboat with burdens was drawn from side to side. The tavern was the most popular catfish-supper tavern on the river drive. Waffles were served with the catfish. A large Staffordshireware platter, printed in clear, dark, beautiful blue, made by the English potter, Stubbs, shows this ferry and tavern, with its broad piazza, and the river with its row of poplar trees. It is shown on page 93. Burnaby enjoyed the catfish-suppers as much as the turtle-feasts, but I doubt if there was a Kissing Bridge in Philadelphia.

Many were the good reasons that could be given to explain and justify attendance at an old-time tavern; one was the fact that often the only newspaper that came to town was kept therein. This dingy tavern sheet often saw hard usage, for when it went its rounds some could scarce read it, some but pretend to read it. One old fellow in Newburyport opened it wide, gazed at it with interest, and cried out to his neighbor in much excitement: “Bad news. Terrible gales, terrible gales, ships all bottom side up,” as indeed they were, in his way of holding the news sheet.

The extent and purposes to which the tavern sheet might be applied can be guessed from the notice written over the mantel-shelf of one taproom, “Gentlemen learning to spell are requested to use last week’s newsletter.”

The old taverns saw many rough jokes. Often there was a tavern butt on whom all played practical jokes. These often ended in a rough fight. The old Collin’s Tavern shown on page 97 was in coaching days a famous tavern in Naugatuck on the road between New Haven and Litchfield. One of the hostlers at this tavern, a burly negro, was the butt of all the tavern hangers-on, and a great source of amusement to travellers. His chief accomplishment was “bunting.” He bragged that he could with a single bunt break down a door, overturn a carriage, or fell a horse. One night a group of jokers promised to give him all the cheeses he could bunt through. He bunted holes through three cheeses on the tavern porch, and then was offered a grindstone, which he did not perceive either by his sense of sight or feeling to be a stone until his alarmed tormentors forced him to desist for fear he might kill himself.

A picturesque and grotesque element of tavern life was found in those last leaves on the tree, the few of Indian blood who lingered after the tribes were scattered and nearly all were dead. These tawnies could not be made as useful in the tavern yard as the shiftless and shifting negro element that also drifted to the tavern, for the Eastern Indian never loved a horse as did the negro, and seldom became handy in the care of horses. These waifs of either race, and half-breeds of both races, circled around the tavern chiefly because a few stray pennies might be earned there, and also because within the tavern were plentiful supplies of cider and rum.

Almost every community had two or three of these semi-civilized Indian residents, who performed some duties sometimes, but who often in the summer, seized with the spirit of their fathers or the influence of their early lives, wandered off for weeks and months, sometimes selling brooms and baskets, sometimes reseating chairs, oftener working not, simply tramping trustfully, sure of food whenever they asked for it. It is curious to note how industrious, orderly Quaker and Puritan housewives tolerated the laziness, offensiveness, and excesses of these half-barbarians. Their uncouthness was endured when they were in health, and when they fell sick they were cared for with somewhat the same charity and forbearance that would be shown a naughty, unruly child.

Often the landlady of the tavern or the mistress of the farm-house, bustling into her kitchen in the gray dawn, would find a sodden Indian sleeping on the floor by the fireplace, sometimes a squaw and pappoose by his side. If the kitchen door had no latch-string out, the Indian would crawl into the hay in the barn; but wherever he slept, he always found his way to the kitchen in good time for an ample breakfast.

Indian women often proved better helpers than the men. One Deb Browner lived a severely respectable life all winter, ever ready to help in the kitchen of the tavern if teamsters demanded meals; always on hand to help dip candles in early winter, and make soap in early spring; and her strong arms never tired. But when early autumn tinted the trees, and on came the hunting season, she tore off her respectable calico gown and apron, kicked off her shoes and stockings, and with black hair hanging wild, donned moccasins and blanket, and literally fled to the woods for a breath of life, for freedom. She took her flitting unseen in the night, but twice was she noted many miles away by folk who knew her, tramping steadily northward, bearing by a metomp of bark around her forehead a heavy burden in a blanket.

One Sabbath morning in May a travelling teamster saw her in her ultra-civilized state on her way home from meeting, crowned, not only with a discreet bonnet, but with a long green veil hanging down her back. She was entering the tavern door to know whether they wished her to attack the big spring washing and bleaching the following day. “Hello, Teppamoy!” he said, staring at her, “how came you here and in them clothes?” Scowling fiercely, she walked on in haughty silence, while the baffled teamster told a group of tavern loafers that he had been a lumberman, and some years there came to the camp in Maine a wild old squaw named Teppamoy who raised the devil generally, but the constable had never caught her, and that she “looked enough like that Mis’ Browner to be her sister.”

Another half-breed Indian, old Tuggie Bannocks, lived in old Narragansett. She was as much negro as Indian and was reputed to be a witch; she certainly had some unusual peculiarities, the most marked being a full set of double teeth all the way round, and an absolute refusal ever to sit on a chair, sofa, stool, or anything that was intended to be sat upon. She would sit on a table, or a churn, or a cradle-head, or squat on the floor; or she would pull a drawer out of a high chest and recline on the edge of that. It was firmly believed that in her own home she hung by her heels on the oaken chair rail which ran around the room. She lived in the only roofed portion of an old tumble-down house that had been at one time a tavern, and she bragged that she could “raise” every one who had ever stopped at that house as a guest, and often did so for company. Oh! what a throng of shadows, some fair of face, some dark of life, would have filled the dingy tavern at her command! I have told some incidents of her life in my Old Narragansett, so will no longer keep her dusky presence here.

Other Indian “walk-abouts,” as tramps were called, lived in the vicinity of Malden, Massachusetts; old “Moll Grush,” who fiercely resented her nickname; Deb Saco the fortune-teller, whose “counterfeit presentment” can be seen in the East Indian Museum at Salem; Squaw Shiner, who died from being blown off a bridge in a gale, and who was said to be “a faithful friend, a sharp enemy, a judge of herbs, a weaver of baskets, and a lover of rum.”

Another familiar and marked character was Sarah Boston. I have taken the incidents of her life from The Hundredth Town, where it is told so graphically. She lived on Keith Hill in Grafton, Massachusetts, an early “praying town” of the Indians. A worn hearthstone and doorstone, surrounded now by green grass and shadowed by dying lilacs, still show the exact spot where once stood her humble walls, where once “her garden smiled.

The last of the Hassanamiscoes (a noble tribe of the Nipmuck race, first led to Christ in 1654 by that gentle man John Eliot, the Apostle to the Indians), she showed in her giant stature, her powerful frame, her vast muscular power, no evidence of a debilitated race or of enfeebled vitality. It is said she weighed over three hundred pounds. Her father was Boston Phillips, also told of in story and tradition for his curious ways and doings. Sarah dressed in short skirts, a man’s boots and hat, a heavy spencer (which was a man’s wear in those days); and, like a true Indian, always wore a blanket over her shoulders in winter. She was mahogany-red of color, with coarse black hair, high cheek-bones, and all the characteristic features of her race. Her great strength and endurance made her the most desired farm-hand in the township to be employed in haying time, in wall-building, or in any heavy farm work. Her fill of cider was often her only pay for some powerful feat of strength, such as stone-lifting or stump-pulling. At her leisure times in winter she made and peddled baskets in true Indian fashion, and told improbable and baseless fortunes, and she begged cider at the tavern, and drank cider everywhere. “The more I drink the drier I am,” was a favorite expression of hers. Her insolence and power of abuse made her dreaded for domestic service, though she freely entered every home, and sat smoking and glowering for hours in the chimney corner of the tavern; but in those days of few house-servants and scant “help,” she often had to be endured that she might assist the tired farm wife or landlady.

A touch of grim humor is found in this tale of her – the more humorous because, in spite of Apostle Eliot and her Christian forbears, she was really a most godless old heathen. She tended with care her little garden, whose chief ornament was a fine cherry tree bearing luscious blackhearts, while her fellow-townsmen had only sour Morellos growing in their yards. Each year the sons of her white neighbors, unrestrained by her threats and entreaties, stripped her tree of its toothsome and beautiful crop before Sarah Boston could gather it. One year the tree hung heavy with a specially full crop; the boys watched eagerly and expectantly the glow deepening on each branch, through tinted red to dark wine color, when one morning the sound of a resounding axe was heard in Sarah’s garden, and a passer-by found her with powerful blows cutting down the heavily laden tree. “Why, Sarah,” he asked in surprise, “why are you cutting down your splendid great cherry tree?” – “It shades the house,” she growled; “I can’t see to read my Bible.”

A party of rollicking Yankee blades, bold with tavern liquor, pounded one night on the wooden gate of the old Grafton burying-ground, and called out in profane and drunken jest, “Arise, ye dead, the judgment day is come.” Suddenly from one of the old graves loomed up in the dark the gigantic form of Sarah Boston, answering in loud voice, “Yes, Lord, I am coming.” Nearly paralyzed with fright, the drunken fellows fled, stumbling with dismay before this terrifying and unrecognized apparition.

Mrs. Forbes ends the story of Sarah Boston with a beautiful thought. The old squaw now lies at rest in the same old shadowy burial place – no longer the jest and gibe of jeering boys, the despised and drunken outcast. Majestic with the calm dignity of death, she peacefully sleeps by the side of her white neighbors. At the dawn of the last day may she once more arise, and again answer with clear voice, “Yes, Lord, I am coming.”

CHAPTER V

“KILL-DEVIL” AND ITS AFFINES

Any account of old-time travel by stage-coach and lodging in old-time taverns would be incomplete without frequent reference to that universal accompaniment of travel and tavern sojourn, that most American of comforting stimulants – rum.

The name is doubtless American. A manuscript description of Barbadoes, written twenty-five years after the English settlement of the island in 1651, is thus quoted in The Academy: “The chief fudling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor.” This is the earliest-known allusion to the liquor rum; the word is held by some antiquaries in what seems rather a strained explanation to be the gypsy rum, meaning potent, or mighty. The word rum was at a very early date adopted and used as English university slang. The oldest American reference to the word rum (meaning the liquor) which I have found is in the act of the General Court of Massachusetts in May, 1657, prohibiting the sale of strong liquors “whether knowne by the name of rumme, strong water, wine, brandy, etc., etc.” The traveller Josselyn wrote of it, terming it that “cursed liquor rhum, rumbullion or kill-devil.” English sailors still call their grog rumbowling. But the word rum in this word and in rumbooze and in rumfustian did not mean rum; it meant the gypsy adjective powerful. Rumbooze or rambooze, distinctly a gypsy word, and an English university drink also, is made of eggs, ale, wine, and sugar. Rumfustian was made of a quart of strong beer, a bottle of white wine or sherry, half a pint of gin, the yolks of twelve eggs, orange peel, nutmeg, spices, and sugar. Rum-barge is another mixed drink of gypsy name. It will be noted that none of these contains any rum.