Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's ships Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836

Robert Fitzroy

Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's ships Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836 Volume I. – Proceedings of the First Expedition, 1826-1830

MY LORD:

I have the honour of dedicating to your lordship, as Head of the Naval Service, this narrative of the Surveying Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836.

Originated by the Board of Admiralty, over which Viscount Melville presided, these voyages have been carried on, since 1830, under his lordship's successors in office.

Captain King has authorized me to lay the results of the Expedition which he commanded, from 1826 to 1830, before your lordship, united to those of the Beagle's subsequent voyages.

I have the honour to be,

MY LORD,

Your lordship's obedient servant,

ROBERT FITZ-ROY.

PREFACE

In this Work, the result of nine years' voyaging, partly on coasts little known, an attempt has been made to combine giving general information with the paramount object – that of fulfilling a duty to the Admiralty, for the benefit of Seamen.

Details, purely technical, have been avoided in the narrative more than I could have wished; but some are added in the Appendix to each volume: and in a nautical memoir, drawn up for the Admiralty, those which are here omitted will be found.

There are a few words used frequently in the following pages, which may not at first sight be familiar to every reader, therefore I need hardly apologize for saying that, although the great Portuguese navigator's name was Magalhaens – it is generally pronounced as if written Magellan: – that the natives of Tierra del Fuego are commonly called Fuegians; – and that Chilóe is thus accented for reasons given in page 384 of the second volume.

In the absence of Captain King, who has entrusted to me the care of publishing his share of this work, I may have overlooked errors which he would have detected. Being hurried, and unwell, while attending to the printing of his volume, I was not able to do it justice.

It may be a subject of regret, that no paper on the Botany of Tierra del Fuego is appended to the first volume. Captain King took great pains in forming and preserving a botanical collection, aided by a person embarked solely for that purpose. He placed this collection in the British Museum, and was led to expect that a first-rate botanist would have examined and described it; but he has been disappointed.

In conclusion, I beg to remind the reader, that the work is unavoidably of a rambling and very mixed character; that some parts may be wholly uninteresting to most readers, though, perhaps, not devoid of interest to all; and that its publication arises solely from a sense of duty.

ROBERT FITZ-ROYLondon, March 1839.

INTRODUCTION

In 1825, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty directed two ships to be prepared for a Survey of the Southern Coasts of South America; and in May, of the following year, the Adventure and the Beagle were lying in Plymouth Sound, ready to carry the orders of their Lordships into execution.

These vessels were well provided with every necessary, and every comfort, which the liberality and kindness of the Admiralty, Navy Board, and officers of the Dock-yards, could cause to be furnished.

On board the Adventure, a roomy ship, of 330 tons burthen, without guns,1 lightly though strongly rigged, and very strongly built, were —

Phillip Parker King, Commander and Surveyor, Senior Officer of the Expedition.

Gunner – Boatswain – and Carpenter.

Serjeant and fourteen Marines; and about forty Seamen and Boys.

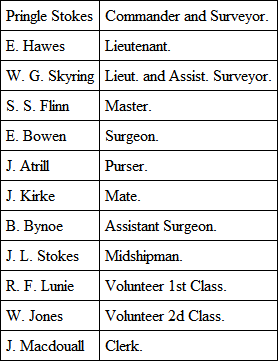

In the Beagle, a well-built little vessel, of 235 tons, rigged as a barque, and carrying six guns, were —

Carpenter.

Serjeant and nine Marines; and about forty Seamen and Boys.

In the course of the voyage, several changes occurred among the officers, which it may be well to mention here.

In September, 1826, Lieutenant Hawes invalided: and was succeeded by Mr. R. H. Sholl, the senior mate in the Expedition.

In February, 1827, Mr. Ainsworth was unfortunately drowned; and, in his place, Mr. Williams acted, until superseded by Mr. S. S. Flinn, of the Beagle.

Lieutenant Cooke invalided in June, 1827; and was succeeded by Mr. J. C. Wickham.

In the same month Mr. Graves received information of his promotion to the rank of Lieutenant.

Between May and December, 1827, Mr. Bowen and Mr. Atrill invalided; besides Messrs. Lunie, Jones, and Macdouall: Mr. W. Mogg joined the Beagle, as acting Purser; and Mr. D. Braily, as volunteer of the second class.

Mr. Bynoe acted as Surgeon of the Beagle, after Mr. Bowen left, until December, 1828.

In August, 1828, Captain Stokes's lamented vacancy was temporarily filled by Lieutenant Skyring; whose place was taken by Mr. Brand.

Mr. Flinn was then removed to the Adventure; and Mr. A. Millar put into his place.

In December, 1828, the Commander-in-chief of the Station (Sir Robert Waller Otway) superseded the temporary arrangements of Captain King, and appointed a commander, lieutenant, master, and surgeon to the Beagle. Mr. Brand then invalided, and the lists of officers stood thus —

Adventure (1828-30).

Phillip Parker King, Commander and Surveyor, Senior Officer of the Expedition.

Gunner – Boatswain – and Carpenter.

Serjeant and fourteen Marines: and about fifty2 Seamen and Boys.

Beagle (1828-30).

Serjeant and nine Marines: and about forty Seamen and Boys.

In June, 1829, Lieutenant Mitchell joined the Adventure; and in February, 1830, Mr. A. Millar died very suddenly: – and very much regretted.

The following Instructions were given to the Senior Officer of the Expedition.

"By the Commissioners for executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, &c.

"Whereas we think fit that an accurate Survey should be made of the Southern Coasts of the Peninsula of South America, from the southern entrance of the River Plata, round to Chilóe; and of Tierra del Fuego; and whereas we have been induced to repose confidence in you, from your conduct of the Surveys in New Holland; we have placed you in the command of His Majesty's Surveying Vessel the Adventure; and we have directed Captain Stokes, of His Majesty's Surveying Vessel the Beagle, to follow your orders.

"Both these vessels are provided with all the means which are necessary for the complete execution of the object above-mentioned, and for the health and comfort of their Ships' Companies. You are also furnished with all the information, we at present possess, of the ports which you are to survey; and nine Government Chronometers have been embarked in the Adventure, and three in the Beagle, for the better determination of the Longitudes.

"You are therefore hereby required and directed, as soon as both vessels shall be in all respects ready, to put to sea with them; and on your way to your ulterior destination, you are to make, or call at, the following places, successively; namely; Madeira: Teneriffe: the northern point of St. Antonio, and the anchorage at St. Jago; both in the Cape Verd Islands: the Island of Trinidad, in the Southern Atlantic: and Rio de Janeiro: for the purpose of ascertaining the differences of the longitudes of those several places.

"At Rio de Janeiro, you will receive any supplies you may require; and make with the Commander-in-chief, on that Station, such arrangements as may tend to facilitate your receiving further supplies, in the course of your Expedition.

"After which, you are to proceed to the entrance of the River Plata, to ascertain the longitudes of the Cape Santa Maria, and Monte Video: you are then to proceed to survey the Coasts, Islands, and Straits; from Cape St. Antonio, at the south side of the River Plata, to Chilóe; on the west coast of America; in such manner and order, as the state of the season, the information you may have received, or other circumstances, may induce you to adopt.

"You are to continue on this service until it shall be completed; taking every opportunity to communicate to our Secretary, and the Commander-in-Chief, your proceedings: and also, whenever you may be able to form any judgment of it, where the Commander-in-Chief, or our Secretary, may be able to communicate with you.

"In addition to any arrangements made with the Admiral, for recruiting your stores, and provisions; you are, of course, at liberty to take all other means, which may be within your reach, for that essential purpose.

"You are to avail yourself of every opportunity of collecting and preserving Specimens of such objects of Natural History as may be new, rare, or interesting; and you are to instruct Captain Stokes, and all the other Officers, to use their best diligence in increasing the Collections in each ship: the whole of which must be understood to belong to the Public.

"In the event of any irreparable accident happening to either of the two vessels, you are to cause the officers and crew of the disabled vessel to be removed into the other, and with her, singly, to proceed in prosecution of the service, or return to England, according as circumstances shall appear to require; understanding that the officers and crews of both vessels are hereby authorized, and required, to continue to perform their duties, according to their respective ranks and stations, on board either vessel to which they may be so removed. Should, unfortunately, your own vessel be the one disabled, you are in that case to take the command of the Beagle: and, in the event of any fatal accident happening to yourself; Captain Stokes is hereby authorized to take the command of the Expedition; either on board the Adventure, or Beagle, as he may prefer; placing the officer of the Expedition who may then be next in seniority to him, in command of the second vessel: also, in the event of your inability, by sickness or otherwise, at any period of this service, to continue to carry the Instructions into execution, you are to transfer them to Captain Stokes, or to the surviving officer then next in command to you, who is hereby required to execute them, in the best manner he can, for the attainment of the object in view.

"When you shall have completed the service, or shall, from any cause, be induced to give it up; you will return to Spithead with all convenient expedition; and report your arrival, and proceedings, to our Secretary, for our information.

"Whilst on the South American Station, you are to consider yourself under the command of the Admiral of that Station; to whom we have expressed our desire that he should not interfere with these orders, except under peculiar necessity.

"Given under our hands the 16th of May 1826.

(Signed) "Melville.

"G. Cockburn.

"To Phillip P. King, Esq., Commander

of His Majesty's Surveying Vessel

Adventure, at Plymouth.

"By command of their Lordships.

(Signed) "J. W. Croker."

On the 22d of May, 1826, the Adventure and Beagle sailed from Plymouth; and, in their way to Rio de Janeiro, called successively at Madeira, Teneriffe, and St. Jago.

Unfavourable weather prevented a boat being sent ashore at the northern part of San Antonio; but observations were made in Terrafal Bay, on the south-west side of the island: and, after crossing the Equator, the Trade-wind hung so much to the southward, that Trinidad could not be approached without a sacrifice of time, which, it was considered, might be prejudicial to more important objects of the Expedition.

Both ships anchored at Rio de Janeiro on the 10th of August, and remained there until the 2d of October, when they sailed to the River Plata.

In Maldonado,3 their anchors were dropped on the 13th of the same month; and, till the 12th of November, each vessel was employed on the north side of the river, between Cape St. Mary and Monte Video.

CHAPTER I

Departure from Monte Video – Port Santa Elena – Geological remarks – Cape Fairweather – Non-existence of Chalk – Natural History – Approach to Cape Virgins, and the Strait of Magalhaens (or Magellan)

We sailed from Monte Video on the 19th of November 1826; and, in company with the Beagle, quitted the river Plata.

According to my Instructions, the Survey was to commence at Cape San Antonio, the southern limit of the entrance of the Plata; but, for the following urgent reasons, I decided to begin with the southern coasts of Patagonia, and Tierra del Fuego, including the Straits of Magalhaens.4 In the first place, they presented a field of great interest and novelty; and secondly, the climate of the higher southern latitudes being so severe and tempestuous, it appeared important to encounter its rigours while the ships were in good condition – while the crews were healthy – and while the charms of a new and difficult enterprize had full force.

Our course was therefore southerly, and in latitude 45° south, a few leagues northward of Port Santa Elena, we first saw the coast of Patagonia. I intended to visit that port; and, on the 28th, anchored, and landed there.

Seamen should remember that a knowledge of the tide is of especial consequence in and near Port Santa Elena. During a calm we were carried by it towards reefs which line the shore, and were obliged to anchor until a breeze sprung up.

The coast along which we had passed, from Point Lobos to the north-east point of Port Santa Elena, appeared to be dry and bare of vegetation. There were no trees; the land seemed to be one long extent of undulating plain, beyond which were high, flat-topped hills of a rocky, precipitous character. The shore was fronted by rocky reefs extending two or three miles from high-water mark, which, as the tide fell, were left dry, and in many places were covered with seals.

As soon as we had secured the ships, Captain Stokes accompanied me on shore to select a place for our observations. We found the spot which the Spanish astronomers of Malaspina's Voyage (in 1798) used for their observatory, the most convenient for our purpose. It is near a very steep shingle (stony) beach at the back of a conspicuous red-coloured, rocky projection which terminates a small bay, on the western side, at the head of the port. The remains of a wreck, which proved to be that of an American whaler, the Decatur of New York, were found upon the extremity of the same point; she had been driven on shore from her anchors during a gale.

The sight of the wreck, and the steepness of the shingle beach just described, evidently caused by the frequent action of a heavy sea, did not produce a favourable opinion of the safety of the port: but as it was not the season for easterly gales, to which only the anchorage is exposed, and as appearances indicated a westerly wind, we did not anticipate danger.

While we were returning on board, the wind blew so strongly that we had much difficulty in reaching the ships, and the boats were no sooner hoisted up, and every thing made snug, than it blew a hard gale from the S.W. The water however, from the wind being off the land, was perfectly smooth, and the ships rode securely through the night: but the following morning the gale increased, and veered to the southward, which threw a heavy sea into the port, placing us, to say the least, in a very uneasy situation. Happily it ceased at sunset. In consequence of the unfavourable state of the weather, no attempt was made to land in order to observe an eclipse of the sun; to make which observation was one reason for visiting this port.

The day after the gale, while I was employed in making some astronomical observations, a party roamed about in quest of game: but with little success, as they killed only a few wild ducks. The fire which they made for cooking communicated to the dry stubbly grass, and in a few minutes the whole country was in a blaze. The flames continued to spread during our stay, and, in a few days, more than fifteen miles along the coast, and seven or eight miles into the interior were overrun by the fire. The smoke very much impeded our observations, for at times it quite obscured the sun.

The geological structure of this part of the country, and a considerable portion of the coast to the north and south, consists of a fine-grained porphyritic clay slate. The summits of the hills near the coast are generally of a rounded form, and are paved, as it were, with small, rounded, siliceous pebbles, imbedded in the soil, and in no instance lying loose or in heaps; but those of the interior are flat-topped, and uniform in height, for many miles in extent. The valleys and lower elevations, notwithstanding the poverty and parched state of the soil, were partially covered with grass and shrubby plants, which afford sustenance to numerous herds of guanacoes. Many of these animals were observed feeding near the beach when we were working into the bay, but they took the alarm, so that upon landing we only saw them at a considerable distance. In none of our excursions could we find any water that had not a brackish taste. Several wells have been dug in the valleys, both near the sea and at a considerable distance from it, by the crews of sealing vessels; but, except in the rainy season, they all contain saltish water. This observation is applicable to nearly the whole extent of the porphyritic country. Oyster-shells, three or four inches in diameter, were found, scattered over the hills, to the height of three or four hundred feet above the sea. Sir John Narborough, in 1652, found oyster-shells at Port San Julian; but, from a great many which have been lately collected there, we know that they are of a species different from that found at Port Santa Elena. Both are fossils.

No recent specimen of the genus Ostrea was found by us on any part of the Patagonian coast. Narborough, in noticing those at Port San Julian, says, "They are the biggest oyster-shells that I ever saw, some six, some seven inches broad, yet not one oyster to be found in the harbour: whence I conclude they were here when the world was formed."

The short period of our visit did not enable us to add much to natural history. Of quadrupeds we saw guanacoes, foxes, cavies, and the armadillo; but no traces of the puma (Felis concolor), or South American lion, although it is to be met with in the interior.

I mentioned that a herd of guanacoes was feeding near the shore when we arrived. Every exertion was made to obtain some of the animals; but, either from their shyness, or our ignorance of the mode of entrapping them, we tried in vain, until the arrival of a small sealing-vessel, which had hastened to our assistance, upon seeing the fires we had accidentally made, but which her crew thought were intended for signals of distress. They shot two, and sent some of the meat on board the Adventure. The next day, Mr. Tarn succeeded in shooting one, a female, which, when skinned and cleaned, weighed 168 lbs. Narborough mentions having killed one at Port San Julian, that weighed, "cleaned in his quarters, 268 lbs." The watchful and wary character of this animal is very remarkable. Whenever a herd is feeding, one is posted, like a sentinel, on a height; and, at the approach of danger, gives instant alarm by a loud neigh, when away they all go, at a hand-gallop, to the next eminence, where they quietly resume their feeding, until again warned of the approach of danger by their vigilant 'look-out.'

Another peculiarity of the guanaco is, the habit of resorting to particular spots for natural purposes. This is mentioned in the 'Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle,' in the 'Encyclopédie Méthodique,' as well as other works.

In one place we found the bones of thirty-one guanacoes collected within a space of thirty yards, perhaps the result of an encampment of Indians, as evident traces of them were observed; among which were a human jaw-bone, and a piece of agate ingeniously chipped into the shape of a spear-head.

The fox, which we did not take, appeared to be small, and similar to a new species afterwards found by us in the Strait of Magalhaens.

The cavia5 (or, as it is called by Narborough, Byron, and Wood, the hare, an animal from which it differs both in appearance and habits, as well as flavour), makes a good dish; and so does the armadillo, which our people called the shell-pig.6 This little animal is found abundantly about the low land, and lives in burrows underground; several were taken by the seamen, and, when cooked in their shells, were savoury and wholesome.

Teal were abundant upon the marshy grounds. A few partridges, doves, and snipes, a rail, and some hawks were shot. The few sea-birds that were observed consisted of two species of gulls, a grebe and a penguin (Aptenodytes Magellanica).

We found two species of snakes and several kinds of lizards. Fish were scarce, as were also insects; of the last, our collections consisted only of a few species of Coleoptera, two or three Lepidoptera, and two Hymenoptera.

Among the sea-shells, the most abundant was the Patella deaurata, Lamk.; this, with three other species of Patella, one Chiton, three species of Mytilus, three of Murex, one of Crepidula, and a Venus, were all that we collected.

About the country, near the sea-shore, there is a small tree, whose stem and roots are highly esteemed for fuel by the crews of sealing-vessels which frequent this coast. They call it 'piccolo.' The leaf was described to me as having a prickle upon it, and the flower as of a yellow colour. A species of berberis also is found, which when ripe may afford a very palatable fruit.

Our short visit gave us no flattering opinion of the fertility of the country near this port. Of the interior we were ignorant; but, from the absence of Indians and the scarcity of fresh water, it is probably very bare of pasturage. Falkner, the Jesuit missionary, says these parts were used by the Tehuelhet tribes for burying-places: we saw, however, no graves, nor any traces of bodies, excepting the jaw-bone above-mentioned; but subsequently, at Sea Bear Bay, we found many places on the summits of the hills which had evidently been used for such a purpose, although then containing no remains of bodies. This corresponds with Falkner's account, that after a period of twelve months the sepulchres are formally visited by the tribe, when the bones of their relatives and friends are collected and carried to certain places, where the skeletons are arranged in order, and tricked out with all the finery and ornaments they can collect.

The ships sailed from Port Santa Elena on the 5th December, and proceeded to the southward, coasting the shore as far as Cape Two Bays.

Our object being to proceed with all expedition to the Strait of Magalhaens, the examination of this part of the coast was reserved for a future opportunity. On the 13th, we had reached within fifty miles of Cape Virgins, the headland at the entrance of the strait, but it was directly in the wind's eye of us. The wind veering to S.S.W., we made about a west course. At day-light the land was in sight, terminating in a point to the S.W., so exactly like the description of Cape Virgins and the view of it in Alison's voyage, that without considering our place on the chart, or calculating the previous twenty-four hours' run, it was taken for the Cape itself, and, no one suspecting a mistake, thought of verifying the ship's position. The point, however, proved to be Cape Fairweather. It was not a little singular, that the same mistake should have been made on board the Beagle, where the error was not discovered for three days.7

From the appearance of the weather I was anxious to approach the land in order to anchor, as there seemed to be every likelihood of a gale; and we were not deceived, for at three o'clock, being within seven miles of the Cape, a strong wind sprung up from the S.W., and the anchor was dropped. Towards evening it blew so hard, that both ships dragged their anchors for a considerable distance.