Man on the Ocean: A Book about Boats and Ships

The famous “Rob Roy” canoe, which is now so much in vogue among boys and young men of aquatic tendency, is constructed and managed on precisely the same principles with the Eskimo kayak; the only difference between the two being that the “Rob Roy” canoe is made of thin wood instead of skin, and is altogether a more elegant vessel. An account of it will be found in our chapter on “Boats.” The South Sea islanders also use a canoe which they propel with a double-bladed paddle similar to that of the Eskimos. They are wonderfully expert and fearless in the management of this canoe, as may be seen from the annexed woodcut.

In order to show that the paddle of the canoe is more natural to man than the oar, we present a picture of the canoe used by the Indians of the Amazon in South America. Here we see thar the savages of the south, like their brethren of the north, sit with their faces to the bow and urge their bark forward by neans of short paddles, without using the gunwale as a fulcrum. The oar is decidedly a more modern and a more scientific instrument than the paddle, but the latter is better suited to some kinds of navigation than the former.

Very different indeed from the light canoes just described are the canoes of the South Sea islanders. Some are large, and some are small; some long, some short; a few elegant, a few clumsy; and one or two peculiarly remarkable. Most of them are narrow, and liable to upset; in order to prevent which catastrophe the natives have ingeniously, though clumsily, contrived a sort of “outrigger,” or plank, which they attach to the side of the canoe to keep it upright. They also fasten two canoes together to steady them.

One of these double canoes is thus described by Cheever in his “Island World of the Pacific:”—“A double canoe is composed of two single ones of the same size placed parallel to each other, three or four feet apart, and secured in their places by four or five pieces of wood, curved just in the shape of a bit-stock. These are lashed to both canoes with the strongest cinet, made of cocoa-nut fibre, so as to make the two almost as much one as same of the double ferry-boats that ply between Brooklyn and New York. A flattened arch is thus made by the bow-like cross-pieces over the space between the canoes, upon which a board or a couple of stout poles laid lengthwise constitute an elevated platform for passengers and freight, while those who paddle and steer sit in the bodies of the canoes at the sides. A slender mast, which may be unstepped in a minute, rises from about the centre of this platform, to give support to a very simple sail, now universally made of white cotton cloth, but formerly of mats.”

The double canoes belonging to the chiefs of the South Sea islanders are the largest,—some of them being nearly seventy feet long, yet they are each only about two feet wide and three or four feet deep. The sterns are remarkably high—fifteen or eighteen feet above the water.

The war canoes are also large and compactly built; the stern being low and covered, so as to afford shelter from stones and darts. A rude imitation of a head or some grotesque figure is usually carved on the stern; while the stem is elevated, curved like the neck of a swan, and terminates frequently in the carved figure of a bird’s head. These canoes are capable of holding fifty warriors. Captain Cook describes some as being one hundred and eight feet long. All of them, whether single or double, mercantile or war canoes, are propelled by paddles, the men sitting with their faces in the direction in which they are going.

As may be supposed, these canoes are often upset in rough weather; but as the South Sea islanders are expert swimmers, they generally manage to right their canoes and scramble into them again. Their only fear on such occasions is being attacked by sharks. Ellis, in his interesting book, “Polynesian Researches,” relates an instance of this kind of attack which was made upon a number of chiefs and people—about thirty-two—who were passing from one island to another in a large double canoe:– “They were overtaken by a tempest, the violence of which tore their canoes from the horizontal spars by which they were united. It was in vain for them to endeavour to place them upright again, or to empty out the water, for they could not prevent their incessant overturning. As their only resource, they collected the scattered spars and boards, and constructed a raft, on which they hoped they might drift to land. The weight of the whole number who were collected on the raft was so great as to sink it so far below the surface that they stood above their knees in water. They made very little progress, and soon became exhausted by fatigue and hunger. In this condition they were attacked by a number of sharks. Destitute of a knife or any other weapon of defence, they fell an easy prey to these rapacious monsters. One after another was seized and devoured, or carried away by them, and the survivors, who with dreadful anguish beheld their companions thus destroyed, saw the number of their assailants apparently increasing, as each body was carried off until only two or three remained.

“The raft, thus lightened of its load, rose to the surface of the water, and placed them beyond the reach of the voracious jaws of their relentless destroyers. The tide and current soon carried them to the shore, where they landed to tell the melancholy fate of their fellow-voyagers.”

Captain Cook refers to the canoes of New Zealand thus:—

“The ingenuity of these people appears in nothing more than in their canoes. They are long and narrow, and in shape very much resemble a New England whale-boat. The larger sort seem to be built chiefly for war, and will carry from forty to eighty or a hundred armed men. We measured one which lay ashore at Tolaga; she was sixty-eight and a half feet long, five feet broad, and three and a half feet deep. The bottom was sharp, with straight sides like a wedge, and consisted of three lengths, hollowed out to about two inches, or one inch and a half thick, and well fastened together with strong plaiting. Each side consisted of one entire plank, sixty-three feet long, ten or twelve inches broad, and about one inch and a quarter thick; and these were fitted and lashed to the bottom part with great dexterity and strength.

“A considerable number of thwarts were laid from gunwale to gunwale, to which they were securely lashed on each side, as a strengthening to the boat. The ornament at the head projected five or six feet beyond the body, and was about four and a half feet high. The ornament at the stern was fixed upon that end as the stern-post of a ship is upon her keel, and was about fourteen feet high, two broad, and one inch and a half thick. They both consisted of boards of carved work, of which the design was much better than the execution. All their canoes, except a few at Opoorage or Mercury Bay, which were of one piece, and hollowed by fire, are built after this plan, and few are less than twenty feet long. Some of the smaller sort have outriggers; and sometimes two are joined together, but this is not common.

“The carving upon the stern and head ornaments of the inferior boats, which seemed to be intended wholly for fishing, consists of the figure of a man, with the face as ugly as can be conceived, and a monstrous tongue thrust out of the mouth, with the white shells of sea-ears stuck in for eyes. But the canoes of the superior kind, which seem to be their men-of-war, are magnificently adorned with openwork, and covered with loose fringes of black feathers, which had a most elegant appearance. The gunwale boards were also frequently carved in a grotesque taste, and adorned with tufts of white feathers placed upon black ground. The paddles are small and neatly made. The blade is of an oval shape, or rather of a shape resembling a large leaf, pointed at the bottom, broadest in the middle, and gradually losing itself in the shaft, the whole length being about six feet. By the help of these oars they push on their boats with amazing velocity.”

Mr Ellis, to whose book reference has already been made, and who visited the South Sea Islands nearly half a century later than Cook, tells us that the single canoes used by some of the islanders are far safer than the double canoes for long voyages, as the latter are apt to be torn asunder during a storm, and then they cannot be prevented from constantly upsetting.

Single canoes are not so easily separated from their outrigger. Nevertheless they are sometimes upset in rough seas; but the natives don’t much mind this. When a canoe is upset and fills, the natives, who learn to swim like ducks almost as soon as they can walk, seize hold of one end of the canoe, which they press down so as to elevate the other end above the sea, by which means a great part of the water runs out; they then suddenly loose their hold, and the canoe falls back on the water, emptied in some degree of its contents. Swimming along by the side of it, they bale out the rest, and climbing into it, pursue their voyage.

Europeans, however, are not so indifferent to being overturned as are the savages. On one occasion Mr Ellis, accompanied by three ladies, Mrs Orsmond, Mrs Barff, and his wife, with her two children and one or two natives, were crossing a harbour in the island of Huahine. A female servant was sitting in the forepart of the canoe with Mr Ellis’s little girl in her arms. His infant boy was at its mother’s breast; and a native, with a long light pole, was paddling or pushing the canoe along, when a small buhoe, with a native youth sitting in it, darted out from behind a bush that hung over the water, and before they could turn or the youth could stop his canoe, it ran across the outrigger. This in an instant went down, the canoe was turned bottom upwards, and the whole party precipitated into the sea.

The sun had set soon after they started from the opposite side, and the twilight being very short, the shades of evening had already thickened round them, which prevented the natives on shore from seeing their situation. The native woman, being quite at home in the water, held the little girl up with one hand, and swam with the other towards the shore, aiding at the same time Mrs Orsmond, who had caught hold of her long hair, which floated on the water behind her. Mrs Barff, on rising to the surface, caught hold of the outrigger of the canoe that had occasioned the disaster, and calling out loudly for help, informed the people on shore of their danger, and speedily brought them to their assistance. Mrs Orsmond’s husband, happening to be at hand at the time, rushed down to the beach and plunged at once into the water. His wife, on seeing him, quitted her, hold of the native woman, and grasping her husband, would certainly have drowned both him and herself had not the natives sprung in and rescued them.

Mahinevahine, the queen of the island, leaped into the sea and rescued Mrs Barff; Mr Ellis caught hold of the canoe, and supported his wife and their infant until assistance came. Thus they were all saved.

The South Sea islanders, of whose canoes we have been writing, are—some of them at least—the fiercest savages on the face of the earth. They wear little or no clothing, and practise cannibalism—that is, man-eating—from choice. They actually prefer human flesh to any other. Of this we are informed on most unquestionable authority.

Doubtless the canoes which we have described are much the same now as they were a thousand years ago; so that, by visiting those parts of the earth where the natives are still savage, we may, as it were, leap backward into ancient times, and behold with our own eyes the state of marine architecture as it existed when our own forefathers were savages, and paddled about the Thames and the Clyde on logs, and rafts, and wicker-work canoes.

Chapter Four.

Ancient Ships and Navigators

Everything must have a beginning, and, however right and proper things may appear to those who begin them, they generally wear a strange, sometimes absurd, aspect to those who behold them after the lapse of many centuries.

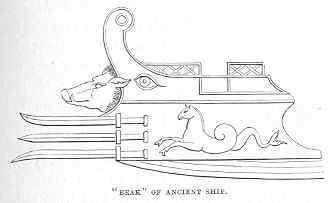

When we think of the trim-built ships and yachts that now cover the ocean far and wide, we can scarce believe it possible that men really began the practice of navigation, and first put to sea, in such grotesque vessels as that represented on page 55.

In a former chapter reference has been made to the rise of commerce and maritime enterprise, to the fleets and feats of the Phoenicians, Egyptians, and Hebrews in the Mediterranean, where commerce and navigation first began to grow vigorous. We shall now consider the peculiar structure of the ships and boats in which their maritime operations were carried on.

Boats, as we have said, must have succeeded rafts and canoes, and big boats soon followed in the wake of little ones. Gradually, as men’s wants increased, the magnitude of their boats also increased, until they came to deserve the title of little ships. These enormous boats, or little ships, were propelled by means of oars of immense size; and, in order to advance with anything like speed, the oars and rowers had to be multiplied, until they became very numerous.

In our own day we seldom see a boat requiring more than eight or ten oars. In ancient times boats and ships required sometimes as many as four hundred oars to propel them.

The forms of the ancient ships were curious and exceedingly picturesque, owing to the ornamentation with which their outlines were broken, and the high elevation of their bows and sterns.

We have no very authentic details of the minutiae of the form or size of ancient ships, but antiquarians have collected a vast amount of desultory information, which, when put together, enables us to form a pretty good idea of the manner of working them, while ancient coins and sculptures have given us a notion of their general aspect. No doubt many of these records are grotesque enough, nevertheless they must be correct in the main particulars.

Homer, who lived 1000 B.C., gives, in his “Odyssey,” an account of ship-building in his time, to which antiquarians attach much importance, as showing the ideas then prevalent in reference to geography, and the point at which the art of ship-building had then arrived. Of course due allowance must be made for Homer’s tendency to indulge in hyperbole.

Ulysses, king of Ithaca, and deemed on of the wisest Greeks who went to Troy, having been wrecked upon an island, is furnished by the nymph Calypso with the means of building a ship,—that hero being determined to seek again his native shore and return to his home and his faithful spouse Penelope.

“Forth issuing thus, she gave him first to wieldA weighty axe, with truest temper steeled,And double-edged; the handle smooth and plain,Wrought of the clouded olive’s easy grain;And next, a wedge to drive with sweepy sway;Then to the neighbouring forest led the way.On the lone island’s utmost verge there stoodOf poplars, pines, and firs, a lofty wood,Whose leafless summits to the skies aspire,Scorched by the sun, or seared by heavenly fire(Already dried). These pointing out to view,The nymph just showed him, and with tears withdrew.“Now toils the hero; trees on trees o’erthrownFall crackling round, and the forests groan;Sudden, full twenty on the plain are strewed,And lopped and lightened of their branchy load.At equal angles these disposed to join,He smoothed and squared them by the rule and line.(The wimbles for the work Calypso found),With those he pierced them and with clinchers bound.Long and capacious as a shipwright formsSome bark’s broad bottom to outride the storms,So large he built the raft; then ribbed it strongFrom space to space, and nailed the planks along.These formed the sides; the deck he fashioned last;Then o’er the vessel raised the taper mast,With crossing sail-yards dancing in the wind:And to the helm the guiding rudder joined(With yielding osiers fenced to break the forceOf surging waves, and steer the steady course).Thy loom, Calypso, for the future sailsSupplied the cloth, capacious of the gales.With stays and cordage last he rigged the ship,And, rolled on levers, launched her on the deep.”

The ships of the ancient Greeks and Romans were divided into various classes, according to the number of “ranks” or “banks,” that is, rows, of oars. Monoremes contained one bank of oars; biremes, two banks; triremes, three; quadriremes, four; quinqueremes, five; and so on. But the two latter were seldom used, being unwieldy, and the oars in the upper rank almost unmanageable from their great length and weight.

Ptolemy Philopator of Egypt is said to have built a gigantic ship with no less than forty tiers of oars, one above the other! She was managed by 4000 men, besides whom there were 2850 combatants; she had four rudders and a double prow. Her stern was decorated with splendid paintings of ferocious and fantastic animals; her oars protruded through masses of foliage; and her hold was filled with grain!

That this account is exaggerated and fanciful is abundantly evident; but it is highly probable that Ptolemy did construct one ship, if not more, of uncommon size.

The sails used in these ships were usually square; and when there was more than one mast, that nearest the stern was the largest. The rigging was of the simplest description, consisting sometimes of only two ropes from the mast to the bow and stern. There was usually a deck at the bow and stern, but never in the centre of the vessel. Steering was managed by means of a huge broad oar, sometimes a couple, at the stern. A formidable “beak” was affixed to the fore-part of the ships of war, with which the crew charged the enemy. The vessels were painted black, with red ornaments on the bows; to which latter Homer is supposed to refer when he writes of red-cheeked ships.

Ships built by the Greeks and Romans for war were sharper and more elegant than those used in commerce; the latter being round bottomed, and broad, in order to contain cargo.

The Corinthians were the first to introduce triremes into their navy (about 700 years B.C.), and they were also the first who had any navy of importance. The Athenians soon began to emulate them, and ere long constructed a large fleet of vessels both for war and commerce. That these ancient ships were light compared with ours, is proved by the fact that when the Greeks landed to commence the siege of Troy they drew up their ships on the shore. We are also told that ancient mariners, when they came to a long narrow promontory of land, were sometimes wont to land, draw their ships bodily across the narrowest part of the isthmus, and launch them on the other side.

Moreover, they had a salutary dread of what sailors term “blue water”—that is, the deep, distant sea—and never ventured out of sight of land. They had no compass to direct them, and in their coasting voyages of discovery they were guided, if blown out to sea, by the stars.

The sails were made of linen in Homer’s time; subsequently sail-cloth was made of hemp, rushes, and leather. Sails were sometimes dyed of various colours and with curious patterns. Huge ropes were fastened round the ships to bind them more firmly together, and the bulwarks were elevated beyond the frame of the vessels by wicker-work covered with skins.

Stones were used for anchors, and sometimes crates of small stones or sand; but these were not long of being superseded by iron anchors with teeth or flukes.

The Romans were not at first so strong in naval power as their neighbours, but in order to keep pace with them they were ultimately compelled to devote more attention to their navies. About 260 B.C. they raised a large fleet to carry on the war with Carthage. A Carthaginian quinquereme which happened to be wrecked on their coast was taken possession of by the Romans, used as a model, and one hundred and thirty ships constructed from it. These ships were all built, it is said, in six days; but this appears almost incredible. We must not, however, judge the power of the ancients by the standard of present times. It is well known that labour was cheap then, and we have recorded in history the completion of great works in marvellously short time, by the mere force of myriads of workmen.

The Romans not only succeeded in raising a considerable navy, but they proved themselves ingenious in the contrivance of novelties in their war-galleys. They erected towers on the decks, from the top of which their warriors fought as from the walls of a fortress. They also placed small cages or baskets on the top of their masts, in which a few men were placed to throw javelins down on the decks of the enemy; a practice which is still carried out in principle at the present day, men being placed in the “tops” of the masts of our men-of-war, whence they fire down on the enemy. It was a bullet from the “top” of one of the masts of the enemy that laid low our greatest naval hero, Lord Nelson.

From this time the Romans maintained a powerful navy. They crippled the maritime power of their African foes, and built a number of ships with six and even ten ranks of oars. The Romans became exceedingly fond of representations of sea-fights, and Julius Caesar dug a lake in the Campus Martius specially for these exhibitions. They were not by any means sham fights. The unfortunates who manned the ships on these occasions were captives or criminals, who fought as the gladiators did—to the death—until one side was exterminated or spared by imperial clemency. In one of these battles no fewer than a hundred ships and nineteen thousand combatants were engaged!

Such were the people who invaded Britain in the year 55 B.C. under Julius Caesar, and such the vessels from which they landed upon our shores to give battle to the then savage natives of our country.

It is a curious fact that the crusades of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were the chief cause of the advancement of navigation after the opening of the Christian era. During the first five hundred years after the birth of our Lord, nothing worthy of notice in the way of maritime enterprise or discovery occurred.

But about this time an event took place which caused the foundation of one of the most remarkable maritime cities in the world. In the year 476 Italy was invaded by the barbarians. One tribe, the Veneti, who dwelt upon the north-eastern shores of the Adriatic, escaped the invaders by fleeing for shelter to the marshes and sandy islets at the head of the gulf, whither their enemies could not follow by land, owing to the swampy nature of the ground, nor by sea, on account of the shallowness of the waters. The Veneti took to fishing, then to making salt, and finally to mercantile enterprises. They began to build, too, on those sandy isles, and soon their cities covered ninety islands, many of which were connected by bridges. And thus arose the far-famed city of the waters—“Beautiful Venice, the bride of the sea.”

Soon the Venetians, and their neighbours the Genoese, monopolised the commerce of the Mediterranean.

The crusades now began, and for two centuries the Christian warred against the Turk in the name of Him who, they seem to have forgotten, if indeed the mass of them ever knew, is styled the Prince of Peace. One of the results of these crusades was that the Europeans engaged acquired a taste for Eastern luxuries, and the fleets of Venice and Genoa, Pisa and Florence, ere long crowded the Mediterranean, laden with jewels, silks, perfumes, spices, and such costly merchandise. The Normans, the Danes, and the Dutch also began to take active part in the naval enterprise thus fostered, and the navy of France was created under the auspices of Philip Augustus.