A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain III

The church is built in form of a cross; a great tower in the middle, in which are eight bells, and two spires at the west end. There is a handsome chapter-house on the north side of the quire.

The length of the church from east to west is 306 feet, of which the choir is – feet; the length of the cross isle from north to south is 121 feet; the breadth of the church 59 feet.

On a pillar at the entrance into the choir, is this inscription:

Sint Reges Nutritii tui & Regina? Nutrices,

Ecclesiam hanc Collegiatam & Parochialem

Fundavit Antiquitas.

Refundavit Illustrissimus Henricus Rex Octavus,

Edwardo Lee Archiepiscopo Eborac. intercedente.

Sancivit Serenissima Elizabetha Regina,

Edvino Sands Eborum Archiepiscopo mediante.

Stabilivit Præpotentissimus Monarcha Jac. Rex,

Henrico Howard Comite Northamp. aliisque

Supplicantibus.

Sint sicut Oreb & Zeb, Zeba & Salmana

Qui dicunt Haereditate possideamus

Sanctuarium Dei.

There are no very remarkable monuments in this church, only one of Archbishop Sands, which is within the communion rails, and is a fair tomb of alabaster, with his effigies lying on it at full length. – Round the verge of it is this inscription: Edvinus Sandes Sacræ Theologiæ Doctor, postquam Vigorniensem Episcopatum Annos X, totidemque tribus demptis Londinensem gessisset Eboracensis sui Archiepiscopatus Anno XII” Vitæ autem LXIX?. obiit Julii X. A. D. 1588.

At the head of the tomb is this inscription:

Cujus hic Reconditum Cadaver jacet, genere non humilis vixit, Dignitate locoque magnus, exemplo major; duplici functus Episcopatu, Archi-Episcopali tandem Amplitudine Illustris. Honores hosce mercatus grandi Pretio, Meritis Virtutibusque Homo hominum a Malitia & Vindicta Innocentissimus; Magnanimus, Apertus, & tantum Nescius adulari; Summe Liberalis atque Misericors: Hospitalissime optimus, Facilis, & in sola Vitia superbus. Scilicet haud minora, quam locutus est, vixit & fuit. In Evangelii prædicand. Laboribus ad extremum usque Halitum mirabiliter assiduus; a sermonibus ejus nunquam non melior discederes. Facundus nolebat esse & videbatur; ignavos, sedulatitis suæ Conscius, oderat. Bonas literas auxit pro Facultatibus; Ecclesiæ Patrimonium, velut rem Deo consecratum decuit, intactum defendit; gratia, qua floruit, apud Illustrissimam mortalium Elizabetham, effecit, ne hanc, in qua jacet, Ecclesiam ti jacentem cerneres. Venerande Præsul! Utrius memorandum Fortunæ exemplar! Qui tanta cura gesseris, multa his majora, animo ad omnia semper impavido, perpessus es; Careares, Exilia, amplissimarum Facultatum amissiones; quodque omnium difficillime Innocens perferre animus censuevit, immanes Calumnias; & si re una votis tuis memor, quod Christo Testimonium etiam sanguine non præbueris; attamen, qui in prosperis tantos fluctus, & post Aronum tot adversa, tandem quietis sempternæ Portum, fessus Mundi, Deique sitiens, reperisti, Æturnum lætare; vice sanguinis sunt sudores tui; abi lector, nec ista scias, tantum ut sciveris, sed ut imiteris.

At the feet under the coat of arms:

Verbum Dei manet in Æternum.

Round the border of another stone in the south isle of the choir.

Hic jacet Robertus Serlby, Generosus, quondam Famulus Willielmi Booth Archiepiscopo Eborac. Qui obiit 24? die Mensis Augusti, A. D. 1480, cujus animæ propitietur Deus. Amen.

On a stone fixed in the wainscot under one of the prebendal stalls in the choir, is this inscription, very antient, but without a date.

Hic jacet Wilhelmus Talbot, miser & indignus sacerdos, expectans Resurrectionem in signo Thau –

I suppose it means a Tau to denote a cross.

On the south-side of the church in the churchyard,

Me Pede quando teris, Homo qui Mortem mediteris Sic contritus eris, & pro me quæro, preceris, without name or date.

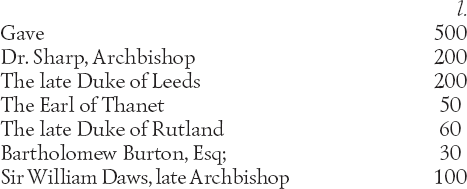

Here was formerly a palace belonging to the Archbishop of York, which stood on the south side of the church, the ruins of which still remain; by which it appears to have been a large and stately palace. It was demolished in the time of the Rebellion against King Charles I. and the church, I have heard, hardly escaped the fury of those times; but was indebted to the good offices of one Edward Cludd, Esq; one of the Parliament side, who lived at Norwood, in the parish of Southwell, in a house belonging to the archbishop, where he lived in good esteem for some time after the Restauration; and left this estate at Norwood, which he held by lease of the archbishop, to his nephew Mr. Bartholomew Fillingham, who was a considerable officer in the Exchequer, and from whom Bartholomew Burton, Esq; who was his nephew and heir, inherited it, with the bulk of all the rest of his estate and who now enjoys it by a lease of three lives, granted by the late Archbishop Sir William Dawes. Here were no less than three parks belonging to the archbishop, which tho’ disparked, still retain the name; one of which is Norwood Park, in which is a good house, which has been very much enlarged and beautified by the said Mr. Burton, who lives in it some part of the year.

There is a free-school adjoining to the church, under the care of the Chapter; where the choristers are taught gratis; and other boys belonging to the town. The master is chosen by the Chapter; and is to be approved by the Archbishop of York.

There are also two fellowships and two scholarships in St. John’s College in Cambridge, founded by Dr. Keton, Canon of Salisbury, in the 22d year of King Henry VIII. to be chosen by the master and fellows of the said college, out of such who have been choristers of the church of Southwell, if any such able person for learning and manners, can be found in Southwell, or in the university of Cambridge; and for want of such, then out of any scholars abiding in Cambridge; which said fellowships are to be thirteen shillings and four-pence each better than any other fellowship of the college.

Hence crossing the forest I came to Mansfield, a market town, but without any remarkables. In my way I visited the noble seat of the Duke of Kingston at Thoresby, of the Duke of Newcastle at Welbeck, and the Marquis of Hallifax at Rufford, of Rugeford Abbey, all very noble seats, tho’ antient, and that at Welbeck especially, beautify’d with large additions, fine apartments, and good gardens; but particularly the park, well stocked with large timber, and the finest kind, as well as the largest quantity of deer that are any where to be seen; for the late duke’s delight being chiefly on horseback and in the chace, it is not to be wondered if he rather made his parks fine than his gardens, and his stables than his mansion-house; yet the house is noble, large, and magnificent.

Hard by Welbeck is Wirksop Mannor, the antient and stately seat of the noble family of Talbot, descended by a long line of ancestors from another family illustrious, though not enobled (of Lovetot’s). This house, (tho’ in its antient figure) is outdone by none of the best and greatest in the county, except Wollaton Hall, already mentioned; and that though it is, as it were, deserted of its noble patrons; the family of Shrewsbury being in the person of the last duke, removed from this side of the country to another fine seat in the west, already mentioned.

From hence leaving Nottinghamshire, the west part abounding with lead and coal, I cross’d over that fury of a river called the Derwent, and came to Derby, the capital of the county.

This is a fine, beautiful, and pleasant town; it has more families of gentlemen in it than is usual in towns so remote, and therefore here is a great deal of good and some gay company: Perhaps the rather, because the Peak being so near, and taking up the larger part of the county, and being so inhospitable, so rugged and so wild a place, the gentry choose to reside at Derby, rather than upon their estates, as they do in other places.

It must be allowed, that the twelve miles between Nottingham and this town, keeping the mid-way between the Trent on the left, and the mountains on the right, are as agreeable with respect to the situation, the soil, and the well planting of the country, as any spot of ground, at least that I have seen of that length, in England.

The town of Derby is situated on the west bank of the Derwent, over which it has a very fine bridge, well built, but antient, and a chapel upon the bridge, now converted into a dwelling-house. Here is a curiosity in trade worth observing, as being the only one of its kind in England, namely, a throwing or throwster’s mill, which performs by a wheel turn’d by the water; and though it cannot perform the doubling part of a throwster’s work, which can only be done by a handwheel, yet it turns the other work, and performs the labour of many hands. Whether it answers the expence or not, that is not my business.

This work was erected by one Soracule, a man expert in making mill-work, especially for raising water to supply towns for family use: But he made a very odd experiment at this place; for going to show some gentlemen the curiosity, as he called it, of his mili, and crossing the planks which lay just above the millwheel; regarding, it seems, what he was to show his friends more than the place where he was, and too eager in describing things, keeping his eye rather upon what he pointed at with his fingers than what he stept upon with his feet, he stepp’d awry and slipt into the river.

He was so very close to the sluice which let the water out upon the wheel, and which was then pulled up, that tho’ help was just at hand, there was no taking hold of him, till by the force of the water he was carried through, and pushed just under the large wheel, which was then going round at a great rate. The body being thus forc’d in between two of the plashers of the wheel, stopt the motion for a little while, till the water pushing hard to force its way, the plasher beyond him gave way and broke; upon which the wheel went again, and, like Jonah’s whale, spewed him out, not upon dry land, but into that part they call the apron, and so to the mill-tail, where he was taken up, and received no hurt at all.

Derby, as I have said, is a town of gentry, rather than trade; yet it is populous, well built, has five parishes, a large marketplace, a fine town-house, and very handsome streets.

In the church of Allhallows, or, as the Spaniards call it, De Todos los Santos, All Saints, is the Pantheon, or Burial-place of the noble, now ducal family of Cavendish, now Devonshire, which was first erected by the Countess of Shrewsbury, who not only built the vault or sepulchre, but an hospital for eight poor men and four women, close by the church, and settled their maintenance, which is continued to this day: Here are very magnificent monuments for the family of Cavendish; and at this church is a famous tower or steeple, which for the heighth and beauty of its building, is not equalled in this county, or in any of those adjacent.

By an inscription upon this church, it was erected, or at least the steeple, at the charge of the maids and batchelors of the town; on which account, whenever a maid, native of the town, was marry’d, the bells were rung by batchelors: How long the custom lasted, we do not read; but I do not find that it is continued, at least not strictly.

The government of this town, for it is a corporation, and sends two burgesses to Parliament, is in a mayor, high-steward, nine aldermen, a recorder, fourteen brothers, fourteen capital burgesses, and a town-clerk: The trade of the town is chiefly in good malt and good ale; nor is the quantity of the latter unreasonably small, which, as they say, they dispose of among themselves, though they spare some to their neighbours too.

The Peak DistrictIt is observable, that as the Trent makes the frontier or bounds of the county of Derby south, so the Dove and the Erwash make the bounds east and west, and the Derwent runs through the center; all of them beginning and ending their course in the same county; for they rise in the Peak, and end in the Trent.

I that had read Cotton’s Wonders of the Peak, in which I always wondered more at the poetry than at the Peak; and in which there was much good humour, tho’ but little good verse, could not satisfy my self to be in Derbyshire, and not see the River Dove, which that gentleman has spent so much doggerel upon, and celebrated to such a degree for trout and grailing: So from Derby we went to Dove-Bridge, or, as the country people call it, Dowbridge, where we had the pleasure to see the river drowning the low-grounds by a sudden shower, and hastning to the Trent with a most outrageous stream, in which there being no great diversion, and travelling being not very safe in a rainy season on that side, we omitted seeing Ashbourn and Uttoxeter, the Utocetum of the antients, two market towns upon that river, and returning towards Derby, we went from thence directly up into the High Peak.

In our way we past an antient seat, large, but not very gay, of Sir Nathaniel Curson, a noted and (for wealth) over great family, for many ages inhabitants of this county. Hence we kept the Derwent on our right-hand, but kept our distance, the waters being out; for the Derwent is a frightful creature when the hills load her current with water; I say, we kept our distance, and contented our selves with hearing the roaring of its waters, till we came to Quarn or Quarden. a little ragged, but noted village, where there is a famous chalybeat spring, to which abundance of people go in the season to drink the water, as also a cold bath. There are also several other mineral waters in this part of the country, as another chalybeat near Quarden or Quarn, a hot bath at Matlock, and another at Buxton, of which in its place; besides these, there are hot springs in several places which run waste into the ditches and brooks, and are taken no notice of, being remote among the mountains, and out of the way of the common resort.

We found the wells, as custom bids us call them, pretty full of company, the waters good, and very physical, but wretched lodging and entertainment; so I resolved to stay till I came to the south, and make shift with Tunbridge or Epsom, of which I have spoken at large in the counties of Surrey and Kent.

From Quarden we advanc’d due north, and, mounting the hills gradually for four or five miles, we soon had a most frightful view indeed among the black mountains of the Peak; however, as they were yet at a distance, and a good town lay on our left called Wirksworth, we turned thither for refreshment; Here indeed we found a specimen of what I had heard before, (viz.) that however rugged the hills were, the vales were every where fruitful, well inhabited, the markets well supplied, and the provisions extraordinary good; not forgetting the ale, which every where exceeded, if possible, what was pass’d, as if the farther north the better the liquor, and that the nearer we approach’d to Yorkshire, as the place for the best, so the ale advanc’d the nearer to its perfection.

Wirksworth is a large well-frequented market town, and market towns being very thin placed in this part of the county, they have the better trade, the people generally coming twelve or fifteen miles to a market, and sometimes much more; though there is no very great trade to this town but what relates to the lead works, and to the subterranean wretches, who they call Peakrills, who work in the mines, and who live all round this town every way.

The inhabitants are a rude boorish kind of people, but they are a bold, daring, and even desperate kind of fellows in their search into the bowels of the earth; for no people in the world out-do them; and therefore they are often entertained by our engineers in the wars to carry on the sap, and other such works, at the sieges of strong fortified places.

This town of Wirksworth is a kind of a market for lead; the like not known any where else that I know of, except it be at the custom-house keys in London. The Barmoot Court, kept here to judge controversies among the miners, that is to say, to adjust subterranean quarrels and disputes, is very remarkable: Here they summon a master and twenty-four jurors, and they have power to set out the bounds of the works under ground, the terms are these, they are empowered to set off the meers (so they call them) of ground in a pipe and a flat, that is to say, twenty nine yards long in the first, and fourteen square in the last; when any man has found a vein of oar in another man’s ground, except orchards and gardens; they may appoint the proprietor cartways and passage for timber, &c. This court also prescribes rules to the mines, and limits their proceedings in the works under ground; also they are judges of all their little quarrels and disputes in the mines, as well as out, and, in a word, keep the peace among them; which, by the way, may be called the greatest of all the wonders of the Peak, for they are of a strange, turbulent, quarrelsome temper, and very hard to be reconciled to one another in their subterraneous affairs.

And now I am come to this wonderful place, the Peak, where you will expect I should do as some others have, (I think, foolishly) done before me, viz. tell you strange long stories of wonders as (I must say) they are most weakly call’d; and that you may not think me arrogant in censuring so many wise men, who have wrote of these wonders, as if they were all fools, I shall give you four Latin lines out of Mr. Cambden, by which you will see there were some men of my mind above a hundred years ago.

Mira alto Pecco tria sunt, barathrum, specus, antrum;Commoda tot, Plumbum, Gramen, Ovile pecus,Tot speciosa simul sunt, Castrum, Balnea, Chatsworth,Plura sed occurrunt, qute speciosa minus.CAMBD., Brit. Fol., 495.Which by the same hand are Englished thus:Nine things that please us at the Peak we see;A cave, a den, a hole, the wonder be;Lead, sheep and pasture, are the useful three.Chatsworth the castle, and the Bath delight;Much more you see; all little worth the sight.Now to have so great a man as Mr. Hobbes, and after him Mr. Cotton, celebrate the trines here, the first in a fine Latin poem, the last in English verse, as if they were the most exalted wonders of the world: I cannot but, after wondering at their making wonders of them, desire you, my friend, to travel with me through this houling wilderness in your imagination, and you shall soon find all that is wonderful about it.

Near Wirksworth, and upon the very edge of Derwent, is, as above, a village called Matlock, where there are several arm springs, lately one of these being secured by a stone wall on every side, by which the water is brought to rise to a due heighth, is made into a very convenient bath; with a house built over it, and room within the building to walk round the water or bath, and so by steps to go down gradually into it.

This bath would be much more frequented than it is, if two things did not hinder; namely, a base, stony, mountainous road to it, and no good accommodation when you are there: They are intending, as they tell us, to build a good house to entertain persons of quality, or such who would spend their money at it; but it was not so far concluded or directed when I was there, as to be any where begun: The bath is milk, or rather blood warm, very pleasant to go into, and very sanative, especially for rheumatick pains, bruises, &c.

For some miles before we come to Matlock, you pass over the hills by the very mouths of the lead-mines, and there are melting-houses for the preparing the oar, and melting or casting it into pigs; and so they carry it to Wirksworth to be sold at the market.

Over against this warm bath, and on the other, or east side of the Derwent, stands a high rock, which rises from the very bottom of the river (for the water washes the foot of it, and is there in dry weather very shallow); I say, it rises perpendicular as a wall, the precipice bare and smooth like one plain stone, to such a prodigious heighth, it is really surprising; yet what the people believed of it surmounted all my faith too, though I look’d upon it very curiously, for they told me it was above four hundred foot high, which is as high as two of our Monuments, one set upon another; that which adds most to my wonder in it is, that as the stone stands, it is smooth from the very bottom of the Derwent to the uppermost point, and nothing can be seen to grow upon it. The prodigious heighth of this tor, (for it is called Matlock Tor) was to me more a wonder than any of the rest in the Peak, and, I think, it should be named among them, but it is not. So it must not be called one of the wonders.

A little on the other side of Wirksworth, begins a long plain called Brassington Moor, which reaches full twelve miles in length another way, (viz.) from Brassington to Buxton. At the beginning of it on this side from Wirksworth, it is not quite so much. The Peak people, who are mighty fond of having strangers shewed every thing they can, and of calling everything a wonder, told us here of another high mountain, where a giant was buried, and which they called the Giant’s Tomb.

This tempted our curiosity, and we presently rod up to the mountain in order to leave our horses, dragoon-like, with a servant. and to clamber up to the top of it, to see this Giant’s Tomb: Here we miss’d the imaginary wonder, and found a real one; the story of which I cannot but record, to shew the discontented part of the rich world how to value their own happiness, by looking below them, and seeing how others live, who yet are capable of being easie and content, which content goes a great way towards being happy, if it does not come quite up to happiness. The story is this:

As we came near the hill, which seemed to be round, and a precipice almost on every side, we perceived a little parcel of ground hedg’d in, as if it were a garden, it was about twenty or thirty yards long, but not so much broad, parallel with the hill, and close to it; we saw no house, but, by a dog running out and barking, we perceived some people were thereabout; and presently after we saw two little children, and then a third run out to see what was the matter. When we came close up we saw a small opening, not a door, but a natural opening into the rock, and the noise we had made brought a woman out with a child in her arms, and another at her foot. N. B. The biggest of these five was a girl, about eight or ten years old.

We asked the woman some questions about the tomb of the giant upon the rock or mountain: She told us, there was a broad flat stone of a great size lay there, which, she said, the people call’d a gravestone; and, if it was, it might well be called a giant’s, for she thought no ordinary man was ever so tall, and she describ’d it to us as well as she could, by which it must be at least sixteen or seventeen foot long; but she could not give any farther account of it, neither did she seem to lay any stress upon the tale of a giant being buried there, but said, if her husband had been at home he might have shown it to us. I snatched at the word, at home! says I, good wife, why, where do you live. Here, sir, says she, and points to the hole in the rock. Here! says I; and do all these children live here too? Yes, sir, says she, they were ail born here. Pray how long have you dwelt here then? said I. My husband was born here, said she, and his father before him. Will you give me leave, says one of our company, as curious as I was, to come in and see your house, dame? If you please, sir, says she, but ’tis not a place fit for such as you are to come into, calling him, your worship, forsooth; but that by the by. I mention it, to shew that the good woman did not want manners, though she liv’d in a den like a wild body.

However, we alighted and went in: There was a large hollow cave, which the poor people by two curtains hang’d cross, had parted into three rooms. On one side was the chimney, and the man, or perhaps his father, being miners, had found means to work a shaft or funnel through the rock to carry the smoke out at the top, where the giant’s tombstone was. The habitation was poor, ’tis true, but things within did not look so like misery as I expected. Every thing was clean and neat, tho’ mean and ordinary: There were shelves with earthen ware, and some pewter and brass. There was, which I observed in particular, a whole flitch or side of bacon hanging up in the chimney, and by it a good piece of another. There was a sow and pigs running about at the door, and a little lean cow feeding upon a green place just before the door, and the little enclosed piece of ground I mentioned, was growing with good barley; it being then near harvest.