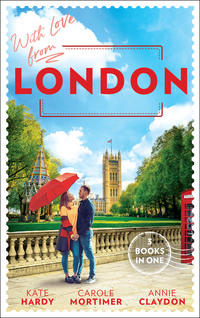

With Love From London

Ironic, because he knew he was guilty of that, too. Not knowing how to challenge his father—because how could you challenge someone when you were always in the wrong?

Maybe. But why leave the property to *me* and not to my mum? It doesn’t make sense.

Pride again? Gabriel suggested. And maybe he thought it would be easier to approach you.

From the grave?

Could be Y-chromosome logic?

That earned him a smiley face.

Georgy, you really need to talk to your mum about it.

I would. Except her phone is switched to voicemail.

Shame.

I know this is crazy, she added, but you were the one I really wanted to talk to about this. You see things so clearly.

It was the first genuine compliment he’d had in a long time—and it was one he really appreciated.

Thank you. Glad I can be here for you. That’s what friends are for.

And they were friends. Even though they’d never met, he felt their relationship was more real and more honest than the ones in his real-life world—where ironically he couldn’t be his real self.

I’m sorry for whining.

You’re not whining. You’ve just been left something by the last person you expected to leave you anything. Of course you’re going to wonder why. And if it is an apology, you’re right that it’s too little, too late. He should’ve patched up the row years ago and been proud of your mum for raising a bright daughter who’s also a decent human being.

Careful, Clarence, she warned. I might not be able to get through the door of the coffee shop when I leave, my head’s so swollen.

Coffee shop? Even though he knew it was ridiculous—this wasn’t the only coffee shop in Surrey Quays, and he had no idea where she worked so she could be anywhere in London right now—Gabriel found himself pausing and glancing round the room, just in case she was there.

But everyone in the room was either sitting in a group, chatting animatedly, or looked like a businessman catching up with admin work.

There was always the chance that Georgygirl was a man, but he didn’t think so. He didn’t think she was a bored, middle-aged housewife posing as a younger woman, either. And she’d just let slip that her newly pregnant mother had been thrown out twenty-nine years ago, which would make her around twenty-eight. His own age.

I might not be able to get through the door of the coffee shop, my head’s so swollen.

Ha. This was the teasing, quick-witted Georgygirl that had attracted him in the first place. He smiled.

We need deflationary measures, then. OK. You need a haircut and your roots are showing. And there’s a massive spot on your nose. It’s like the red spot on Mars. You can see it from outer space.

Jupiter’s the one with the red spot, she corrected. But I get the point. Head now normal size. Thank you.

Good.

And he just bet she knew he’d deliberately mixed up his planets. He paused.

Seriously, though—maybe you could sell the property and split the money with your mum.

It still feels like thirty pieces of silver. I was thinking about giving her all of it. Except I’ll have to persuade her because she’ll say he left it to me.

Or maybe it isn’t an apology—maybe it’s a rescue.

Rescue? How do you work that out? she asked.

You hate your job.

She’d told him that a while back—and, being in a similar situation, he’d sympathised.

If you split the money from selling the property with your mum, would it be enough to tide you over for a six-month sabbatical? That might give you enough time and space to find out what you really want to do. OK, so your grandfather wasn’t there when your mum needed him—but right now it looks to me as if he’s given you something that you need at exactly the right time. A chance for independence, even if it’s only for a little while.

I never thought of it like that. You could be right.

It is what it is. You could always look at it as a belated apology, which is better than none at all. He wasn’t there when he should’ve been, but he’s come good now.

Hmm. It isn’t residential property he left me.

It’s a business?

Yes. And it hasn’t been in operation for a while.

A run-down business, then. Which would take money and time to get it back in working order—the building might need work, and the stock or the fixtures might be well out of date. So he’d been right in the first place and the bequest had come with strings.

Could you get the business back up and running?

Though it would help if he knew what kind of business it actually was. But asking would be breaking the terms of their friendship—because then she’d be sharing personal details.

In theory, I could. Though I don’t have any experience in the service or entertainment industry.

He did. He’d grown up in it.

That’s my area, he said.

He was taking a tiny risk, telling her something personal—but she had no reason to connect Clarence with Hunter Hotels.

My advice, for what it’s worth—an MBA and working for a very successful hotel chain, though he could hardly tell her that without her working out exactly who he was—is that staff are the key. Look at what your competitors are doing and offer your clients something different. Keep a close eye on your costs and income, and get advice from a business start-up specialist. Apply for all the grants you can.

It was solid advice. And Nicole knew that Clarence would be the perfect person to brainstorm ideas with, if she decided to keep the Electric Palace. She was half tempted to tell him everything—but then they’d be sharing details of their real and professional lives, which was against their agreement. He’d already told her too much by letting it slip that he worked in the service or entertainment industry. And she’d as good as told him her age. This was getting risky; it wasn’t part of their agreement. Time to back off and change the subject.

Thank you, she typed. But enough about me. You said you’d had a bad day. What happened?

A pointless row. It’s just one of those days when I feel like walking out and sending off my CV to half a dozen recruitment agencies. Except it’s the family business and I know it’s my duty to stay.

Because he was still trying to make up for the big mistake he’d made when he was a teenager? He’d told her the bare details one night, how he was the disgraced son in the family, and that he was never sure he’d ever be able to change their perception of him.

Clarence, maybe you need to talk to your dad or whoever runs the show in your family business about the situation and say it’s time for you all to move on. You’re not the same person now as you were when you were younger. Everyone makes mistakes—and you can’t spend the rest of your life making up for it. That’s not reasonable.

Maybe.

Clarence must feel as trapped as she did, Nicole thought. Feeling that there was no way out. He’d helped her think outside the box and see her grandfather’s bequest another way: that it could be her escape route. Maybe she could do the same for him.

Could you recruit someone to replace you?

There was a long silence, and Nicole thought maybe she’d gone too far.

Nice idea, Georgy, but it’s not going to happen.

OK. What about changing your role in the business instead? Could you take it in a different direction, one you enjoy more?

It’s certainly worth thinking about.

Which was a polite brush-off. Just as well she hadn’t given in to the urge to suggest meeting for dinner to talk about it.

Because that would’ve been stupid.

Apart from the fact that she wasn’t interested in dating anyone ever again, for all she knew Clarence could be in a serious relationship. Living with someone, engaged, even married.

Even if he wasn’t, supposing they met and she discovered that the real Clarence was nothing like the online one? Supposing they really didn’t like each other in real life? She valued his friendship too much to risk losing it. If that made her a coward, so be it.

Changing his role in the business. Taking it in a different direction. Gabriel could just imagine the expression on his father’s face if he suggested it. Shock, swiftly followed by, ‘I saved your skin, so you toe the line and do what I say.’

It wasn’t going to happen.

But he appreciated the fact that Georgygirl was trying to think about how to make his life better.

For one mad moment, he almost suggested she should bring details of the business she’d just inherited and meet him for dinner and they could brainstorm it properly. But he stopped himself. Apart from the fact that it was none of his business, supposing they met and he discovered that the real Georgygirl was nothing like the online one? Supposing they loathed each other in real life? He valued his time talking to her and he didn’t want to risk losing her friendship.

Thanks for making me feel human again, he typed.

Me? I didn’t do anything. And you gave me some really good advice.

That’s what friends are for. And you did a lot, believe me. He paused. I’d better let you go. I’m due back in the office. Talk to you later?

I’m due back at the office, too. Talk to you tonight.

Good luck. Let me know how it goes with your mum.

Will do. Let me know how it goes with your family.

Sure.

Though he had no intention of doing that.

CHAPTER TWO

BY THE TIME Nicole went to the restaurant to meet her mother that evening, she had a full dossier on the Electric Palace and its history, thanks to the Surrey Quays forum website. Brian Thomas had owned the cinema since the nineteen-fifties, and it had flourished in the next couple of decades; then it had floundered with the rise of multiplex cinemas and customers demanding something more sophisticated than an old, slightly shabby picture house. One article even described the place as a ‘flea-pit’.

Then there were the photographs. It was odd, looking at pictures that people had posted from the nineteen-sixties and realising that the man behind the counter in the café was actually her grandfather, and at the time her mother would’ve been a toddler. Nicole could definitely see a resemblance to her mother in his face—and to herself. Which made the whole thing feel even more odd. This particular thread was about the history of some of the buildings in Surrey Quays, but it was turning out to be her personal history as well.

Susan hardly ever talked about her family, so Nicole didn’t have a clue. Had the Thomas family always lived in Surrey Quays? Had her mother grown up around here? If so, why hadn’t she said a word when Nicole had bought her flat, three years ago? Had Nicole spent all this time living only a couple of streets away from the grandparents who’d rejected her?

And how was Susan going to react to the news of the bequest? Would it upset her and bring back bad memories? The last thing Nicole wanted to do was to hurt her mother.

She’d just put the file back in her briefcase when Susan walked over to their table and greeted her with a kiss.

‘Hello, darling. I got here as fast as I could. Though it must be serious for you not to be at work at this time of day.’

Half-past seven. When most normal people would’ve left the office hours ago. Nicole grimaced as her mother sat down opposite her. ‘Mum. Please.’ She really wasn’t in the mood for another lecture about her working hours.

‘I know, I know. Don’t nag. But you do work too hard.’ Susan frowned. ‘What’s happened, love?’

‘You know I went to see that solicitor today?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ve been left something in a will.’ Nicole blew out a breath. ‘I don’t think I can accept it.’

‘Why not?’

There was no way to say this tactfully. Even though she’d been trying out and discarding different phrases all day, she hadn’t found the right words. So all she could do was to come straight out with it. ‘Because it’s the Electric Palace.’

Understanding dawned in Susan’s expression. ‘Ah. I did wonder if that would happen.’

Her mother already knew about it? Nicole stared at her in surprise. But how?

As if the questions were written all over her daughter’s face, Susan said gently, ‘He had to leave it to someone. You were the obvious choice.’

Nicole shook her head. ‘How? Mum, I pass the Electric Palace every day on my way to work. I had no idea it was anything to do with us.’

‘It isn’t,’ Susan said. ‘It was Brian’s. But I’m glad he’s finally done the right thing and left it to you.’

‘But you’re his daughter, Mum. He should’ve left it to you, not to me.’

‘I don’t want it.’ Susan lifted her chin. ‘Brian made his choice years ago—he decided nearly thirty years ago that I wasn’t his daughter and he is most definitely not my father. I don’t need anything from him. What I own, I have nobody to thank for but myself. I worked for it. And that’s the way I like it.’

Nicole reached over and squeezed her mother’s hand. ‘And you wonder where I get my stubborn streak?’

Susan gave her a wry smile. ‘I guess.’

‘I can’t accept the bequest,’ Nicole said again. ‘I’m going to tell the solicitor to make the deeds over to you.’

‘Darling, no. Brian left it to you, not to me.’

‘But you’re his daughter,’ Nicole said again.

‘And you’re his granddaughter,’ Susan countered.

Nicole shrugged. ‘OK. Maybe I’ll sell to the developer who wants it.’

‘And you’ll use the money to do something that makes you happy?’

It was the perfect answer. ‘Yes,’ Nicole said. ‘Giving the money to you will make me very happy. You can pay off your mortgage and get a new car and go on holiday. It’d be enough for you to go and see the Northern Lights this winter, and I know that’s top of your bucket list.’

‘Absolutely not.’ Susan folded her arms. ‘You using that money to get out of that hell-hole you work in would make me much happier than if I spent a single penny on myself, believe me.’

Nicole sighed. ‘It feels like blood money, Mum. How can I accept something from someone who behaved so badly to you?’

‘Someone who knew he was in the wrong but was too stubborn to apologise. That’s where we both get our stubborn streak,’ Susan said. ‘I think leaving the cinema to you is his way of saying sorry without actually having to use the five-letter word.’

‘That’s what Cl—’ Realising what she was about to give away, Nicole stopped short.

‘Cl—?’ Susan tipped her head to one side. ‘And who might this “Cl—” be?’

‘A friend,’ Nicole said grudgingly.

‘A male friend?’

‘Yes.’ Given that they’d never met in real life, there was always the possibility that her internet friend was actually a woman trying on a male persona for size, but Nicole was pretty sure that Clarence was a man.

‘That’s good.’ Susan looked approving. ‘What’s his name? Cliff? Clive?’

Uh-oh. Nicole could actually see the matchmaking gleam in her mother’s eye. ‘Mum, we’re just friends.’ She didn’t want to admit that they’d never actually met and Clarence wasn’t even his real name; she knew what conclusion her mother would draw. That Nicole was an utter coward. And there was a lot of truth in that: Nicole was definitely a coward when it came to relationships. She’d been burned badly enough last time to make her very wary indeed.

‘You are allowed to date again, you know,’ Susan said gently. ‘Yes, you picked the wrong one last time—but don’t let that put you off. Not all men are as spineless and as selfish as Jeff.’

It was easier to smile and say, ‘Sure.’ Though Nicole had no intention of dating Clarence. Even if he was available, she didn’t want to risk losing his friendship. Wanting to switch the subject away from the abject failure that was her love life, Nicole asked, ‘So did you grow up in Surrey Quays, Mum?’

‘Back when it was all warehouses and terraced houses, before they were turned into posh flats.’ Susan nodded. ‘We lived on Mortimer Gardens, a few doors down from the cinema. Those houses were knocked down years ago and the land was redeveloped.’

‘Why didn’t you say anything when I moved here?’

Susan shrugged. ‘You were having a hard enough time. You seemed happy here and you didn’t need my baggage weighing you down.’

‘So all this time I was living just round the corner from my grandparents? I could’ve passed them every day in the street without knowing who they were.’ The whole thing made her feel uncomfortable.

‘Your grandmother died ten years ago,’ Susan said. ‘When they moved from Mortimer Gardens, they lived at the other end of Surrey Quays from you, so you probably wouldn’t have seen Brian, either.’

Which made Nicole feel very slightly better. ‘Did you ever work at the cinema?’

‘When I was a teenager,’ Susan said. ‘I was an usherette at first, and then I worked in the ticket office and the café. I filled in and helped with whatever needed doing, really.’

‘So you would probably have ended up running the place if you hadn’t had me?’ Guilt flooded through Nicole. How much her mother had lost in keeping her.

‘Having you,’ Susan said firmly, ‘is the best thing that ever happened to me. The moment I first held you in my arms, I felt this massive rush of love for you and that’s never changed. You’ve brought me more joy over the years than anyone or anything else. And I don’t have a single regret about it. I never have and I never will.’

Nicole blinked back the sudden tears. ‘I love you, Mum. And I don’t mean to bring back bad memories.’

‘I love you, too, and you’re not bringing back bad memories,’ Susan said. ‘Now, let’s order dinner. And then we’ll talk strategy and how you’re going to deal with this.’

A plate of pasta and a glass of red wine definitely made Nicole feel more human.

‘There’s a lot about the cinema on the Surrey Quays website. There’s a whole thread with loads of pictures.’ Nicole flicked into her phone and showed a few of them to her mother.

‘Obviously I was born in the mid-sixties so I don’t remember it ever being called The Kursaal,’ Susan said, ‘but I do remember the place from the seventies on. There was this terrible orange and purple wallpaper in the foyer. You can see it there—just be thankful the photo’s black and white.’ She smiled. ‘I remember queuing with my mum and my friends to see Disney films, and everyone being excited about Grease—we were all in love with John Travolta and wanted to look like Sandy and be one of the Pink Ladies. And I remember trying to sneak my friends into Saturday Night Fever when we were all too young to get in, and Brian spotting us and marching us into his office, where he yelled at us and said we could lose him his cinema licence.’

‘So there were some good times?’ Nicole asked.

‘There are always good times, if you look for them,’ Susan said.

‘I remember you taking me to the cinema when I was little,’ Nicole said. ‘Never to the Electric Palace, though.’

‘No, never to the Electric Palace,’ Susan said quietly. ‘I nearly did—but if Brian and Patsy weren’t going to be swayed by the photographs I sent of you on every birthday and Christmas, they probably weren’t going to be nice to you if they met you, and I wasn’t going to risk them making you cry.’

‘Mum, that’s so sad.’

‘Hey. You have the best godparents ever. And we’ve got each other. We didn’t need them. We’re doing just fine, kiddo. And life is too short not to be happy.’ Susan put her arm around her.

‘I’m fine with my life as it is,’ Nicole said.

Susan’s expression said very firmly, Like hell you are. But she said, ‘You know, it doesn’t have to be a cinema.’

‘What doesn’t?’

‘The Electric Palace. It says here on that website that it was a ballroom and an ice rink when it was first built—and you could redevelop it for the twenty-first century.’

‘What, turn it back into a ballroom and an ice rink?’

‘No. When you were younger, you always liked craft stuff. You could turn it into a craft centre. It would do well around here—people wanting to chill out after work.’ Susan gave her a level look. ‘People like you who spend too many hours behind a corporate desk and need to do something to help them relax. Look how popular those adult colouring books are—and craft things are even better when they’re part of a group thing.’

‘A craft centre.’ How many years was it since Nicole had painted anything, or sewn anything? She missed how much she enjoyed being creative, but she never had the time.

‘And a café. Or maybe you could try making the old cinema a going concern,’ Susan suggested. ‘You’re used to putting in long hours, but at least this time it’d be for you instead of giving up your whole life to a job you hate.’

Nicole almost said, ‘That’s what Clarence suggested,’ but stopped herself in time. She didn’t want her mother knowing that she’d shared that much with him. It would give Susan completely the wrong idea. Nicole wasn’t romantically involved with Clarence and didn’t intend to be. She wasn’t going to be romantically involved with anyone, ever again.

‘Think about it,’ Susan said. ‘Isn’t it time you found something that made you happy?’

‘I’m perfectly happy in my job,’ Nicole lied.

‘No, you’re not. You hate it, but it makes you financially secure so you’ll put up with it—and I know that’s my fault because we were so poor when you were little.’

Nicole reached over the table and hugged her. ‘Mum, I never felt deprived when I was growing up. You were working three jobs to keep the rent paid and put food on the table, but you always had time for me. Time to give me a cuddle and tell me stories and do a colouring book with me.’

‘But you’re worried about being poor again. That’s why you stick it out.’

‘Not so much poor as vulnerable,’ Nicole corrected softly. ‘My job gives me freedom from that because I don’t have to worry if I’m going to be able to pay my mortgage at the end of the month—and that’s a good thing. Having a good salary means I have choices. I’m not backed into a corner because of financial constraints.’

‘But the hours you put in don’t leave you time for anything else. You don’t do anything for you—and maybe that’s what the Electric Palace can do for you.’

Nicole doubted that very much, but wanted to avoid a row. ‘Maybe.’

‘Did the solicitor give you the keys?’

Nicole nodded. ‘Shall we go and look at it, then have coffee and pudding back at my place?’

‘Great idea,’ Susan said.

The place was boarded up; all they could see of the building was the semi-circle on the top of the façade at the front and the pillars on either side of the front door. Nicole wasn’t that surprised when the lights didn’t work—the electricity supply had probably been switched off—but she kept a mini torch on her key-ring, and the beam was bright enough to show them the inside of the building.

Susan sniffed. ‘Musty. But no damp, hopefully.’

‘What’s that other smell?’ Nicole asked, noting the unpleasant acridness.

‘I think it might be mice.’

Susan’s suspicions were confirmed when they went into the auditorium and saw how many of the plush seats looked nibbled. Those that had escaped the mice’s teeth were worn threadbare in places.

‘I can see why that article called it a flea-pit,’ Nicole said with a shudder. ‘This is awful, Mum.’

‘You just need the pest control people in for the mice, then do a bit of scrubbing,’ Susan said.

But when they came out of the auditorium and back into the foyer, Nicole flashed the torch around and saw the stained glass. ‘Oh, Mum, that’s gorgeous. And the wood on the bar—it’s pitted in places, but I bet a carpenter could sort that out. I can just see this bar restored to its Edwardian Art Deco glory.’

‘Back in its earliest days?’ Susan asked.

‘Maybe. And look at this staircase.’ Nicole shone the torch on the sweeping wrought-iron staircase that led up to the first floor. ‘I can imagine movie stars sashaying down this in high heels and gorgeous dresses. Or glamorous ballroom dancers.’