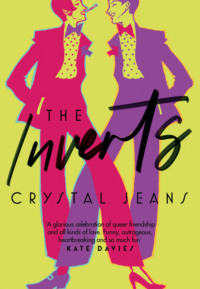

The Inverts

THE INVERTS

Crystal Jeans

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2021

Copyright © Crystal Jeans 2021

Crystal Jeans asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design and illustration by Andrew Davis

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008365875

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2021 ISBN: 9780008365882

Version: 2021-02-09

Dedication

To Renn

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Crystal Jeans

About the Publisher

Prologue

They were quiet for a while, sipping their drinks and smoking, Bart’s leg draped over Bettina’s. Two empty champagne bottles lay on top of the bedsheets, dripping out their dregs onto the purple silk and creating perfect dark circles.

‘Wouldn’t it be awful,’ said Bart, eventually, ‘if we ended up hating each other?’

‘Oh, I would hate that,’ said Bettina.

‘You would hate the hate?’

‘Yes, I’d abhor it. You’re my absolute favourite person.’

‘Same,’ he said, smiling. ‘I am my absolute favourite person.’

‘Bart!’ She nudged him with her elbow, causing his drink to slosh inside the glass. ‘You pretend you’re joking but you aren’t really.’

‘I was joking,’ he said. ‘Possibly.’ He puffed on his cigarette with little smirk creases along the side of his mouth. ‘In any case, I fucking adore you and if things ever soured between us I think a part of my soul would shrivel up. The scant ember of optimism in my heart would go out and I’d become an altogether bleaker human being.’

‘Likewise,’ said Bettina. ‘I would become a crone, living in the shadows. A hag. I’d never be invited to parties.’ She pulled a sad face and he laughed. ‘We must promise to be kind to each other, always,’ she continued. ‘Kind and tolerant. And we mustn’t be dreadful hypocrites about everything.’

‘No,’ agreed Bart. ‘And we must always try to have fun. Because otherwise, what’s the point?’

‘Cheers to that.’

They clinked glasses and drank.

‘Cheers to the queers,’ said Bettina.

‘Hurrah for the inverts!’ said Bart.

They splurted out laughter.

‘I love that we’re funny,’ said Bart. ‘It’s my favourite thing about us.’

‘Me too,’ said Bettina, stubbing out her cigarette. ‘And I love that I’m the funnier one.’ She turned onto her side, as did he, wiggling his behind into the dip of her crotch. He grabbed her arm and wrapped it around himself. ‘You be the big spoon.’

Chapter 1

January 1990, Silverbeach Residential Home, Brighton

The snow was settling thick and deep, in a way it rarely did this close to the shore. Tabitha was not a good driver, had never been a good driver, and driving in snow gave her a sinus headache. But her son was drunk. Look at him, she kept saying to herself. He was side-slumped in the passenger seat, his face smearing the window. Just look at him. She pulled up onto Silverbeach Drive. The car ahead was parked at a 90-degree angle to the kerb and most of the snow on its bonnet had been scooped off. She lit a menthol cigarette and shook her son by the shoulders. ‘Freddy. Freddy.’

‘OK, OK, I’m awake.’ He had a crease like a bracket around one eye from where his cheek had been pressed to the glass.

‘Look,’ she said, pointing through the windscreen. There was a news crew gathered outside the home – three men and a woman standing near a BBC van, all wrapped in winter coats and scarves with puffs of fog coming out of their mouths.

‘Fucking vultures,’ said Freddy.

‘Well, of course they’re vultures, darling. Will you comb your hair, please?’

He looked in the rear-view mirror and ran his fingers through his greying curly hair. He needed a haircut and a shave. Probably a wash. He’d been blessed with such lovely looks, his grandfather’s looks, and now his stomach bulged out like a darts player’s and his earholes were clogged with thick black hair and dead skin cells. Frankly, it was wasteful.

‘Do eat some breath mints,’ she said. ‘You know they’ll want to talk to us.’

Frowning, he helped himself to one of her cigarettes and tucked it in the corner of his mouth. ‘How shocked they’ll be that Bettina and Bartholomew Dawes spawned a bunch of pissheads. What a gobsmacking revelation.’

‘Speak for yourself.’ She went into the glove compartment and pulled out some Mint Imperials. ‘Please,’ she said, holding out the tin.

‘After my fag,’ he said, taking a handful. ‘Can the heating go any higher?’

‘No.’ She watched as the front door of Silverbeach opened and a care worker stuck her head out. She said something to the reporters and closed the door. ‘Probably telling them to bugger off,’ said Tabitha. ‘I don’t know what they’re hoping to achieve. I mean, are they honestly expecting my eighty-five-year-old mother to Zimmer her way out into the snow and confess to a murder that happened half a century ago? Preposterous. Freddy?’

‘I’m listening.’ He was fiddling with the heating knob.

‘I told you it was on full. Why don’t you ever—’

‘OK. Just checking.’ He rubbed his hands together, blowing on them. ‘I personally would love to see Nana swan out here and confess to murder. In a Givenchy gown and her old fox fur, with a piss-bag strapped to her ankle.’

‘Don’t be mean.’

‘With a cigarette holder longer than her arm. Remember that one with the diamonds going in little spirals? “I, Bettina Dawes, wife to the great thespian of yesteryear, Bartholomew Dawes, have a confession to make.”’ He tilted up his chin and smoke wafted from his nose in an oyster-white plume. ‘“The gun belonged to me! I murdered him. And goddammit, I’d do it again! Oh, bother, one seems to have shat oneself. Nurse!”’ He hunched over laughing, spilling the mints onto the floor of the car.

‘She’s nothing like that, Freddy. And she’s not incontinent. Hurry up and finish your cigarette.’ She took her lipstick out of her purse and reapplied – her lips in their natural state had lost entirely all their colour. She was getting pouchy little flabs under her mouth, at the corners, and she hadn’t enjoyed a jawline in twenty years. So bloody what? She was a sixty-one-year-old lawyer specialising in wills and probate. Nobody would expect her to look fantastic. Except … well, they might. Because look at her parents.

Freddy stubbed out his cigarette. ‘Showtime.’

As they pushed open their doors and got out, the female reporter’s head snapped around.

‘Oh, look out,’ said Freddy. ‘She’s got a whiff of carrion.’

‘Don’t you dare say anything rude,’ said Tabitha. ‘Take my arm, please.’

‘What am I supposed to say to them when they ask questions?’

‘No comment. Say you don’t know anything. If they mention the gun, say you knew nothing about it.’

‘I don’t know anything about it. Nobody knows anything about it.’

‘If they ask about your grandfather—’

‘Which they undoubtedly will—’

‘No comment. Just say no comment. Like in the films. And for God’s sake, don’t let them smell your breath.’

The snow under their shoes gave way in a flumpy-soft crunch. Tabitha almost lost her footing on a wedge of crystallised snow and Freddy held her up, barely, his feet skidding. The houses in this street were huge, with three levels and long, ploughed drives within beautiful landscaped gardens. Not too dissimilar to the sort of house she’d grown up in, actually. Possibly even a little inferior. The reporters watched their slow approach. She’d had dealings with reporters before, but never the predatory sort. Just magazine journalists wanting to ask the same tiresome questions about her parents. ‘Retrospective,’ was the word they often used. The last one had been trying to draw parallels between her mother and Zelda Fitzgerald, which was ridiculous and trite. Most asked about her father, who after all had been the more well-known of the two, and were often a smidge sycophantic, trying – quite transparently – to make her feel like an important person: but that was to be expected, and she didn’t mind indulging them. Only it all felt a little pointless. Because everything had already been said. Until now.

They were roughly six car-lengths from the home. ‘Do you think she did it?’ said Freddy, quietly.

‘Of course not.’

‘She did hate him though.’

‘So? You hate your wife and your boss. Do you plan to murder them?’

‘I don’t hate Theresa. I intensely dislike her.’

‘I just can’t imagine Mum doing such a thing. I’ve thought about it and thought about it and—’

‘Maybe he took her gin away.’

‘Oh, shut up, Freddy.’

‘Prised it out of her vice-like alky grip.’

‘Shhh.’ Two car-lengths away now. The reporters were still watching, but not with much interest. There were a dozen or so public photographs of Tabitha with her parents, but most were ancient; Christmas family portrait shots of the Joan Crawford variety: oh, how her father had hated – positively loathed – posing for those! His sarcastic quips to the photographer: ‘Look how fucking wholesome we are!’ His whisky within reach on the bureau, just out of shot. The most recent picture of Tabitha with her mother, published in Tatler in 1958, showed them at the Royal Opera. Tabitha’s face was partly obscured by her hair, deliberately so, and of course she looked so much younger, with her once-cherished jawline and a pair of lips unstripped of their rosy melanin. It was possible these reporters wouldn’t even recognise her.

And they didn’t.

‘Morning,’ said one of them, a young man – a child, practically – with his hair worn in bleached-blond curtains.

‘Morning,’ said Tabitha.

The female reporter was looking down at a clipboard, a steaming cup in her gloved hand.

A care worker let them in, glancing peevishly at the reporters before closing the door with admirable placidity. The home was warm, as it usually was, and this sudden change in temperature set off a tingle in Tabitha’s toes.

‘They’ve been here since six,’ said the carer, whose name might have been Lindsey.

‘Eager little beavers,’ said Freddy, kicking the welcome mat to shake the snow off his shoes.

‘The police were here earlier, too,’ said the carer. ‘For questioning.’

‘Yes, we were informed by the manager,’ said Tabitha.

‘Cup of tea?’ said the carer.

‘Coffee,’ said Freddy. ‘Strong, three sugars.’

‘Not for me, thanks,’ said Tabitha. ‘Can we see her?’

‘Of course. She’s in her room. Fancied some alone time – can’t say I blame her. Give us a shout if there’s an issue.’

‘Can I have some biscuits with my coffee?’ said Freddy.

A playful smile. ‘I’ll see what I can do, my love. Two tics.’

‘She prefers men to women,’ said Tabitha, beginning to climb the stairs. ‘I can always tell. I hate women like that.’

‘I love women like that.’

Her mother’s room was on the second floor at the back of the house, with a view of the garden. She was often found in an armchair by the window, reading a large-print book through her pearl-handled magnifying glass, a plastic beaker full of sherry – sometimes gin – on her tray-table and a cigarette smouldering in an ashtray next to the whining, squealing hearing aids she refused to wear. The carers had tried to ration her alcohol once and she’d threatened to go on hunger strike (which was laughable), and the senior carer decided that since Mrs Dawes was still in full possession of her faculties, she was free to drink herself to death.

She was in her armchair now, looking out of the window. Her book lay closed on the carpet, the magnifying glass placed on top. She looked like she always did – fat and sunken with one oedemic leg propped up on a footstool, but her silver hair immaculate and all her best jewellery on, a floral silk scarf tied around the neck that hung fat and super-soft like a post-pregnancy apron. An uneaten breakfast of poached eggs on toast was on her tray-table, pushed away. With warped fingers she held her beaker of sherry tight to her stomach, as if afraid someone was going to take it away. The room smelled of bananas going bad.

‘Tabby, darling. I’m so glad you could make it. Freddy, oh! I didn’t know you were coming. Come and have a drink! Tabby, where’s your brother?’

‘Still in the States. How are you feeling?’

‘Bloody awful.’ She pointed out of the window. ‘The bastards keep sneaking round the back to try to get photos of me. They won’t leave me alone.’

‘Empty your bedpan over their heads,’ said Freddy.

‘What did he say?’ said her mother.

‘Nothing.’

Freddy leaned in closer. ‘I said, empty your bedpan over their heads.’

She laughed. ‘I should, shouldn’t I? Only I don’t have a bedpan, darling. I have my own en-suite lavatory. Sherry?’

‘I shouldn’t,’ said Freddy, grinning. ‘But I will.’

Tabitha made a point of looking at her watch – it wasn’t even lunchtime yet, for God’s sake – but Freddy didn’t notice. He took the sherry from the cabinet and poured himself a glass. Hanging above the cabinet was an original Hannah Gluckstein of an androgynous woman in a beret. On the opposite wall was a Romaine Brooks watercolour – not a very good one – and underneath, a bookcase full of her mother’s books.

‘Top me up, there’s a good boy,’ said Bettina, holding out her beaker. She gave her daughter a defensive look. ‘Well, it’s either drink or cry. Don’t judge me – I’ll be dead soon.’ She picked up her cigarette from the ashtray and took a puff, her jaw wobbling as she let the smoke out. ‘They won’t leave me alone, darling, honestly – it’s awful. I feel like Quasimodo up in his bell tower. I think they’ve been throwing gravel at the window. Mind you, better the BBC than those fatheads at ITV. They’ve been here since early this morning, darling. In the snow. Honestly. It’s either drink or cry. Drink or die.’

Tabitha sat down on her mother’s bed and lit a menthol. ‘You can hardly blame them, Mum. It’s juicy stuff.’

‘It’s absolute horseshit. What would I be doing with a gun? Really? Your father would—’

A smattering of tiny stones hit the windowpane and her mother startled, spilling her sherry onto her crotch.

Chapter 2

September 1921, Wadley House, Brighton

It couldn’t be – he wouldn’t bloody dare. She opened her window and squinted out into the granular black night. He wouldn’t dare though. He’d have to be blasted off his father’s spirits, throwing stones and shouting his head off like that, with Heinous Henry just yards away, him with his nose like a beak, like a huge disgusting puffin’s beak, rummaging around in everyone’s business, plucking out grubs.

‘Who’s there?’ It might even be one of the drunks from the munitions factory her father owned, someone recently fired. One of them had once shat into the bird bath and lopped all the rose heads from their stems.

‘I would speak with you!’

It was him. Bart. Under the giant oak with his back to the trunk and his whole form in shadow.

‘“Love grew apace, rocked by the anxious beating of this poor heart, which the cruel wanton boy took for a cradle!”’

He was doing Cyrano de Bergerac again. ‘What are you doing?’ she hissed. ‘Go home!’

‘Never in a trillion years!’ Yes, drunk. His late father had left behind an impressive collection of liquors and spirits, the bottles carefully arranged, labels facing out, on top of two large bureaus in his dank and terrifying study. Some were imported from countries as far away as Japan and South Africa (and some dating back to the eighteenth century). Bart’s mother Lucille had felt reluctant to part with them or drink them, so there they still stood, testament to Frederick Dawes’s passion for accumulating rare and exotic fancies, the big joke being that he’d been teetotal; he might as well have been a cripple who collected running shoes or a whore who collected chastity belts. Bart was always taking a nip here and there of the less rare stuff. And he was annoying enough when sober.

‘Go away,’ she said again, glancing at the butler’s dim window – the servants’ quarters stuck out of the main house like the bottom of the letter L and Heinous Henry’s room was across from her, diagonally so. He was most likely still downstairs, seeing to the accounts or bullying the cook, but you could never be sure. She imagined him – the awful creep – crouched below his windowpane, eyes greed-shiny in the gloom, ear cocked, hands down his trousers. And why imagine him with his hands in his trousers? What did that have to do with anything? Anyway, he was an awful, awful creep. ‘Go away,’ she repeated. ‘I’m bored of you already. Genuinely.’

Bart stepped out from the dark, stopping under the high lantern. ‘Come down to me or I’ll wake up the whole fucking house, Bettina.’

Another glance at the butler’s window. ‘The house is still awake, you turnip – it’s only ten. Go home.’

‘I’m going to start singing. I’m going to sing. I really will – you know I will. I’ll tell everyone that you tempted me with your flame-red tresses and your gorgeous wobbly boobies. You tart. I’m going to start singing.’

‘Christ.’ He was always trying to get her into trouble. He minimised the consequences because he had in his head that her parents were these easy-going, liberal-minded poodles, when in fact they were just playing a part and cared deeply what the old guard thought of them – even those they made fun of, such as the parson and his wife, who had ‘such sticks up their backsides, they were basically God’s lollipops’, but heaven forbid that Venetia and Montgomery Wyn Thomas ever express a contrary opinion in their presence, atrocious frauds that they were.

‘Go to our spot, I’ll come and meet you. If I get caught I shall kick you where it hurts.’

He fell to his knees, hand on his heart. ‘Oh, please don’t make promises you cannot keep, my goddess.’

‘I actually hate you.’

A small wood stood between Wadley House and the beach. Bettina loved this wood and as a child had considered it her own private playground, imagining faeries and wood-imps and will-o’-the-wisps behind every tree, and sometimes spying on the maids as they swam half naked in the waterlogged ditch they mistook for a lake. The moon was bright and the clouds sparse, allowing just enough illumination to see by. Bettina knew her way perfectly well, having made this journey thousands of times over her life and many of these in the dark (thanks to Bart), but still her slippers stumbled over rocks and into dips in the dry cracked mud – she hadn’t dared bring a light of her own; there were too many eyes around here, twitching bright eyes like gold coins. She picked up a snapped-off branch and used it like a blind man’s stick. Her robe was red. But it had no hood. And wolves did not exist in this part of England, not any more.

‘Absurd,’ she said to herself, in a whisper. ‘Absolutely raving.’

Soon the wood faded, its trees growing sparser, its tangled undergrowth turning to pale, shorn grass. The sea lay ahead of her, its dark rolling mass swallowing the panorama. The moon was bright out here, in the open, without its pauper’s beard of trees, causing a silvery gleam to coat the flat pebbles which preceded the sandy beach. She followed the thin boardwalk, seeing a small light up ahead, coming from under the pavilion. Her father had had it erected on Armistice Day, and for days afterwards it was kept lit through the night and was filled with drunk, exuberant people who tossed booze from their glasses as they danced uninhibited to live brass music or sat shivering in their winter coats and scarves with slippery smiles on their faces. One man had got so drunk that he went in the sea for a swim – this in the early hours of the morning – and got stunned by the freezing waters and was swept out with the current and drowned. Idiot. He’d been an unmarried schoolteacher, supposedly, from the boys’ college. His death had been like a bucket of slop thrown over the party and the revellers went home finally and returned to their daily, sober miseries.

This was three years ago and still the pavilion stood, its steel rivets super-rusted by the salted air, the canvas awnings covered in gull shit, one half drooped and sulking. Bart was sitting on the ground inside with a paraffin lamp at his side, casting a defiant orb of light around him. In his lap was a bottle of rum, which was apt, since he looked as drunk as a sailor, his blond-tipped lashes bobbing under the weight of collapsing eyelids.

She’d played with Bart from a young age, since they were babies practically, and still they were monkey-nut close, writing daily letters to each other during term time and meeting by night in the holidays (her father, being a hypocrite and a tyrant, didn’t approve of their spending time alone together). They had the same sense of humour, affecting a dry, ironic outlook, and they eschewed exclamation marks in their correspondence and looked down on earnest people. Sarcasm, contrary to popular belief, was the highest form of humour. Everyone else was wrong. Everyone else was stupid.

Bettina sat down opposite him, legs crossed, and fixed him with her most withering look (she practised these looks in the mirror). ‘Bartholomew, you bastard,’ she said, punching his shoulder. ‘Dragging me out here at this hour.’ She hit him again and he tried to bat her hand away. ‘I could’ve been eaten by wolves, you awful nightmare.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.