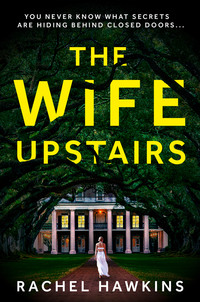

The Wife Upstairs

He smiles again, and something tingles at the base of my spine. “I can deal with Tier One.”

I smile back, relaxing a little. “And no, I’m not staying in Mountain Brook. My friend’s place is in Center Point.”

Center Point is an ugly little town about twenty miles away, once part of the suburban sprawl of Birmingham, now a haven of strip malls and fast-food joints. There are still nice neighborhoods tucked in and around it, but on the whole, it feels like another planet compared to Thornfield Estates, and Eddie’s expression reflects that.

“Shit,” he says, straightening up. “That’s quite a hike from here.”

It is, and my crappy car probably can’t take it much longer, but it’s worth it to me, leaving behind all that ugliness for this place with its manicured lawns and brick houses. I knew it would’ve been smarter to find work in Center Point, like John, but as soon as I’d moved in, the first thing I’d done was look for ways to escape.

So, I didn’t mind the drive.

“There wasn’t much work in Center Point,” I tell him, which is another half-truth. There were jobs—cashier at the Dollar General, checkout girl at Winn-Dixie, cleaner at the “Fit Not Fat!” gym that used to be a Blockbuster Video—but they weren’t jobs that I wanted. That would get me any closer to the type of person I wanted to be. “And my friend knew someone who worked at Roasted in the village, and that’s where I met Mrs. Reed. Well, I met Bear first, I guess.”

At the sound of his name, the dog wags his tail, thumping against the base of my stool, a reminder that I should probably get going. But Eddie is still watching me, and I can’t seem to stop talking. “He was tied up outside, and I brought him some water. Apparently, I was the first person he hadn’t growled at since Mrs. Reed got him, and she asked if I ever did any dog-walking, so now …”

“So now here you are,” Eddie finishes up, lifting one shoulder in a shrug. The movement is elegant despite his wrinkled clothes, and I like how his lips are caught somewhere halfway between a smile and a smirk.

“Here I am,” I say, and for a moment, he holds my gaze. His eyes are very blue, but they’re rimmed in red, and his stubble is dark against his pale skin.

The house is well taken care of and clean, but something about the feeling of emptiness inside of it—and the emptiness in Eddie’s eyes—reminds me of Tripp Ingraham. I hate walking his dog because then I have to go into that stuffy, shut-up house where it’s as if the pause button was hit the second his wife died.

And then I remember that Tripp’s wife didn’t die alone. She and her best friend were both killed in a boating accident just six months back. I never registered the friend’s name because to be honest, I hadn’t really cared about old gossip, but now I wish I had.

Was. He’d said was.

“And I’ve kept you from your work by nearly running you over, then forcing you to make small talk with me,” Eddie says, and I smile, turning my mug around in my hands.

“I like the small talk. Could’ve done without the near-death experience.”

He laughs again, and I suddenly wish I didn’t have anywhere else to be, that I could sit here talking with him the rest of the day.

“Another cup?” he asks, and even though I still have half my coffee left, I push the mug away.

“No, I should probably get going. Let Bear finish up his walk.”

Eddie puts his own mug in the smaller sink there by the coffee-maker. All the houses have that because god forbid rich people have to walk the extra three feet to use the main sink, I guess.

“How many dogs are you walking in the neighborhood?” he asks as I slide off the stool, reaching for Bear’s leash.

“Four right now,” I tell him. “Well, five, the Clarks have two. So five dogs, four families.”

“Could you squeeze in a sixth?”

I pause as Bear pushes himself to his feet, stretching.

“You have a dog?” I ask.

He smiles at me again, a real smile this time, and my heart turns a neat flip in my chest.

“I’m going to get one.”

“Since when does Eddie Rochester have a dog?”

Mrs. Clark—Emily, I’m actually supposed to call her by her first name—is smiling.

She’s always smiling, probably to show off those perfect veneers that must have cost a fortune. Emily is just as thin as Mrs. Reed and just as rich, but rather than Mrs. Reed’s cute sweater sets, Emily is always wearing expensive athletic wear. I’m not sure if she actually goes to the gym, but she spends every second looking like she’s waiting for a yoga class to break out. She’s holding a monogrammed coffee thermos now, the E printed in bold pink on a floral background, and even with that smile, I don’t miss the hard look in her eyes. One thing growing up in the foster system taught me was to watch people’s eyes more than you listened to what they said. Mouths were good at lying, but eyes usually told the truth.

“He just got her,” I reply. “Last week, I think.”

I knew it had been last week because Eddie had been as good as his word. He’d adopted the Irish setter puppy, Adele, the day after we met. I’d started walking her the next day, and apparently Emily had seen me because her first question this morning had been, “Whose dog were you walking yesterday?”

Emily sighs and shakes her head, one fist propped on a narrow hip. Her rings catch the light, sending sprays of little rainbows over her white cabinets. She has a lot of those rings, so many she can’t wear them all.

So many she hasn’t noticed that one, a ruby solitaire, went missing two weeks ago.

“Maybe that’ll help,” she says, and then she leans in a little closer, like she’s sharing a secret.

“His wife died, you know,” she says, the words almost a whisper. Her voice drops to nearly inaudible on died, like just saying the word out loud will bring death knocking at her door or something. “Or at least, we presume. She’s been missing for six months, so it’s not looking good.”

“I heard that,” I say, nonchalant, like I hadn’t gone home last night and googled Blanche Ingraham, like I hadn’t sat in the dark of my bedroom and read the words, Also missing and presumed dead is Bea Rochester, founder of the Southern Manors retail empire.

And that I hadn’t then looked up Bea Rochester’s husband.

Edward.

Eddie.

The joy that had bloomed in my chest reading that article had been a dark and ugly thing, the sort of emotion I knew I wasn’t supposed to feel, but I couldn’t really make myself care. He’s free, she’s gone, and now I have an excuse to see him every week. An excuse to be in that gorgeous home in this gorgeous neighborhood.

“It was so. Sad,” Emily drawls, apparently determined to hash out the entire thing for me. Her eyes are bright now. Gossip is currency in this neighborhood, and she’s clearly about to make it rain.

“Bea and Blanche were like this.” Twisting her index and middle finger together, she holds them up to my face. “They’d been best friends forever, too. Since they were, like, little bitty.”

I nod, as if I have any idea what it’s like to have a best friend. Or to have known someone since I was little bitty.

“Eddie and Bea had a place down at Smith Lake, and Blanche and Tripp used to go down there with them all the time. But the boys weren’t there when it happened.”

The boys. Like they’re seventh graders and not men in their thirties.

“I don’t even know why they took the boat out because Bea didn’t really like it. That was always Eddie’s thing, but I bet he never gets on a boat again.”

She’s watching me again, her dark eyes narrowed a little, and I know she wants me to say something, or to look shocked or maybe even eager. It’s no fun to spill gossip if the recipient seems bored, so that’s why I keep my face completely neutral, no more interest than if we were talking about the weather.

It’s satisfying, watching her strive to get a reaction out of me.

“That all sounds really awful,” I offer up.

Lowering her voice, Emily leans in even closer. “They still don’t even really know what happened. The boat was found out in the middle of the lake, no lights on. Blanche’s and Bea’s things were all still inside the house. Police think they must’ve had too much to drink and decided to take the boat out, but then fallen overboard. Or one fell and the other tried to help her.”

Another head shake. “Just real, real sad.”

“Right,” I say, and this time, it’s a little harder to fake not caring. There’s something about that image, the boat in the dark water, one woman scrabbling against the side of the boat, the other leaning down to help her only to fall in, too …

But it must not show on my face because Emily’s smile is more a grimace now, and there’s something a little robotic in her shrug as she says, “Well, it was tough on all of us, really. A blow to the whole neighborhood. Tripp is just a mess, but I guess you know that.”

Again, I don’t say anything. Mess does not even begin to describe Tripp. Just the other day, he asked if I’d start packing up some of his wife’s things for him, since he can’t bring himself to do it. I was going to refuse because spending any more time in that house seems like a fucking nightmare, but he’s offered to pay me double, so I’m thinking about it.

Now I just watch Emily with a bland expression. Finally, she sighs and says, “Anyway, if Eddie’s getting a dog, maybe that’s a sign that he’s moving on. He didn’t seem to take it as hard as Tripp did, but then he didn’t depend on Bea like Tripp did on Blanche. I swear, that boy couldn’t go to the bathroom before asking Blanche if she thought that was a good idea. Eddie wasn’t like that with Bea, but god, he was broken up.”

Her dark hair brushes her shoulder blades as she swings her head to look at me again. “He was crazy about her. We all were.”

I fight down the bitter swell in my chest, thinking back to the one photo I pulled up of Bea Rochester on my laptop. She was strikingly beautiful, but Eddie is handsome, more so than most of the husbands around here, so it’s not a surprise that they were a matched set.

“I’m sure it was a really big loss,” I say, and finally, Emily waves me and the dogs away with one hand.

“I’ll probably be gone when you get back, so just put them in the crate in the garage.”

I take Major and Colonel for their walk, and sure enough, Emily’s SUV is missing when we return. Their little fluffy bodies tremble with excitement as I settle them in the crate. Major and Colonel are the smallest of all the dogs I walk, and the ones who seems to least enjoy the exercise.

“I know how you feel, dudes,” I tell them as I close the latch, watching Major sink into a dog bed that costs more than I make in a couple of weeks.

Which is why I don’t feel all that bad taking the sterling silver dog tag from his collar and slipping it into my pocket.

“You’re late on your half of the rent.”

I look up from my spot on the couch. I’ve only been home for ten minutes and had hoped I might miss John this afternoon. He’s an office assistant at a local church, plus he works with the Youth Music Ministry, whatever that actually means—I’ve never been a big churchgoer—and his hours are never as set as I’d like. This is hardly the first time I’ve come home to find him standing in the kitchen, his hip propped against the counter, one of my yogurts in his hand.

He always eats my food, no matter how many times I put my name on it, or where I try to hide it in our admittedly tiny kitchen. It’s like nothing in this apartment belongs to me since it was John’s place first, and he’s letting me live here. He opens my bedroom door without knocking, he uses my shampoo, he eats my food, he “borrows” my laptop. He’s skinny and short, a wisp of a guy, really, but sometimes it feels like he sucks up all the space in our shared 700 square feet.

Another reason I want to get out.

Living with John was only ever supposed to be a temporary thing. It was risky, going back to someone who knew my past, but I’d figured it would just be a place to land for a month, maybe six weeks, while I figured out what to do next.

But that was six months ago, and I’m still here.

Lifting my feet off the coffee table, I stand, digging into my pocket for the wad of twenties I shoved in there after my visit to the pawnshop this afternoon.

I don’t always get rid of the stuff I take. The money has never been the point, after all. It’s the having I’ve always enjoyed, plus knowing they’ll never notice anything is missing. It makes me feel like I’ve won something.

But dog-walking isn’t bringing in enough to cover everything yet, so today, I’d plucked Mrs. Reed’s lone diamond earring from the pile of treasures on my dresser, and while I didn’t get nearly what it was worth, it’s enough to cover my half of this shitty concrete box.

I shove it into John’s free hand, pretending I don’t notice the way his fingers try to slide against mine, searching for even a few seconds of extra contact. I’m another thing in this apartment that John would consume if he could, but we both pretend we don’t know that.

“How’s the whole dog-walking thing going?” John asks as I cross back over to our sad couch. He’s got a bit of yogurt stuck to the corner of his mouth, but I don’t bother pointing it out. It’ll probably stay there all day, too, forming a crust that’ll creep out some girl down at the Student Baptist Center where John volunteers a few nights a week.

I already feel solidarity with her, this unknown girl, my sister in Vague Disgust for John Rivers.

Maybe that’s what makes me smile as I sit back down, yanking the ancient afghan blanket out from under me. “Great, actually. Have a few new clients now, so it keeps me pretty busy.”

John’s spoon scrapes against the plastic tub of yogurt—my yogurt— and he watches me, his dark hair hanging limply over one eye.

“Clients,” he snorts. “Makes you sound like a hooker.”

Only John could try to shame a girl for something as wholesome as dog-walking, but I brush it off. If things keep going as well as they’re going, soon I won’t have to live here with him anymore. Soon I can get my own place with my own stuff and my own fucking yogurt that I’ll actually get to eat.

“Maybe I am a hooker,” I reply, picking up the remote off the coffee table. “Maybe that’s what I’m actually doing, and I’m just telling you I walk dogs.”

I twist on the couch to look at him.

He’s still standing by the fridge, but his head is ducked even lower now, his eyes wary as he watches me.

It makes me want to go even further, so I do.

“That could be blowjob money in your pocket now, John. What would the Baptists think about that?”

John flinches from my words, his hand going to his pocket, either to touch the money or to try to hide the boner he probably popped at hearing me say blowjob.

Eddie wouldn’t cringe at a joke like that, I suddenly think.

Eddie would laugh. His eyes would do that thing where they seem brighter, bluer, all because you’ve surprised him.

Like he did when you noticed the books.

“You ought to come to church with me,” he says. “You could come this afternoon.”

“You work in the office,” I say, “not the actual church. Not sure what good it would do me watching you file old newsletters.”

I’m not normally this openly rude to him, aware that he could kick me out since this place is technically all his, but I can’t seem to help myself. It’s something about that day in Eddie’s kitchen. I’ve known enough new beginnings to recognize when something is clicking into place, and I think—know—that my time in this shitty box with this shitty human is ticking down.

“You’re a bitch, Jane,” John mutters sullenly, but he throws away the empty yogurt and gathers his things, slinking out the door without another word.

Once he’s gone, I hunt through the cabinets for any food he hasn’t taken. Luckily, I still have two things of Easy Mac left, and I heat them both up, dumping them into one bowl before hunkering down with my laptop and pulling up my search on Bea Rochester.

I don’t spend much time on the articles about her death. I’ve heard the gossip, and honestly, it seems pretty basic to me—two ladies got too drunk at their fancy beach house, got on their fancy boat, and then succumbed to a very fancy death. Sad, but not exactly a tragedy.

No, what I want to know about is Bea Rochester’s life. What it was that made a man like Eddie want her. Who she was, what their relationship might have looked like.

The first thing I pull up is her company’s website.

Southern Manors.

“Nothing says Fortune 500 company like a bad pun,” I mutter, stabbing another bite of macaroni with my fork.

There’s a letter on the first page of the site, and my eyes immediately scan down to see if Eddie wrote it.

He didn’t. There’s another name there, Susan, apparently Bea’s second-in-command. It’s full of the usual stuff you’d expect when the founder of a company dies suddenly. How sad they are, what a loss, how the company will continue on, burnishing her legacy, etc., etc.

I wonder what kind of a legacy it is, really, selling overpriced cutesy shit.

Clicking from page to page, I take in expensive Mason jars, five-hundred-dollar sweaters with HEY, Y’ALL! stitched discreetly in the left corner, silver salad tongs whose handles are shaped like bees.

There’s so much gingham it’s like Dorothy Gale exploded on this website, but I can’t stop looking, can’t keep from clicking one item, then another.

The monogrammed dog leashes.

The hammered-tin watering cans.

A giant glass bowl in the shape of an apple someone has just taken a bite out of.

It’s all expensive but useless crap, the kind of stuff lining the gift tables at every high-society wedding in Birmingham, and I finally click away from the orgy of pricey/cutesy, going back to the main page to look at Bea Rochester’s picture again.

She’s standing in front of a dining room table made of warm, worn-looking wood. Even though I haven’t been in the dining room at the Rochester mansion, I know immediately that this is theirs, that if I looked a little deeper into the house, I would find this room. It has the same vibe as the living room—nothing matches exactly, but it somehow goes together, from the floral velvet seat covers on the eight chairs to the orange-and-teal centerpiece that pops against the eggplant-colored drapes.

Bea pops, too, her dark hair swinging just above her shoulders in a glossy long bob. She has her arms crossed, her head slightly tilted to one side as she smiles at the camera, her lipstick the prettiest shade of red I think I’ve ever seen.

She’s wearing a navy sweater, a thin gold belt around her waist, and a navy-and-white gingham pencil skirt that manages to be cute and sexy at the same time, and I almost immediately hate her.

And also want to know everything about her.

More googling, the Easy Mac congealing in its bowl on John’s scratched and water-ringed coffee table, my fingers moving quickly, my eyes and my mind filling up with Bea Rochester.

There’s not as much as I’d want, though. She wasn’t famous, really. It’s the company people seem to care about, the stuff they can buy, while Bea seemed to keep herself out of the spotlight.

There’s only one interview I can find—with Southern Living, of course, big surprise. In the accompanying photo, Bea sits at another dining room table—seriously, did this woman exist in any other rooms of a house?—wearing yellow this time, a crystal bowl of lemons on her elbow, an enamel coffee cup printed with daisies casually held in one hand.

The profile is a total puff piece. Bea grew up in Alabama, one of her ancestors was a senator in the 1800s, and they’d had a gorgeous home in some place called Calera that had burned down a few years ago. Her mother had sadly passed away not long after Bea started Southern Manors, and she “did everything in memory of her.”

My eyes keep scanning past the details I already know—the Randolph-Macon degree, the move back to Birmingham, the growth of her business—until I finally snag on Eddie’s name.

Three years ago, Bea Mason met Edward Rochester on vacation in Hawaii. “I was definitely not looking for a relationship,” she laughs. “I just wanted some downtime to read a few books and drink ridiculous frozen drinks. But when Eddie showed up …”

She trails off and shakes her head slightly with a becoming blush. “The whole thing was such a whirlwind, but I always say marrying Eddie was the only impulsive decision I’ve ever made. Luckily, it ended up being the best decision I ever made, too.”

Sighing, I sit back from my laptop, my back protesting, my legs slightly numb from how long I’ve had them folded up under me. The throw over my thighs smells like cheap detergent, and I push it away, wrinkling my nose.

Hawaii.

Why does that make it worse for some reason? Why did I want them to have met at church or the country club or one of the other five thousand boring and safe locations around here?

Because I wanted it not to be special, I think. I wanted her not to be special.

But she is. Beautiful and smart and a millionaire. A woman who built something all her own, even if she did come from money and the kind of background that made achieving shit a hell of a lot easier than it did for someone like me.

I stare at that picture some more, wondering what her voice sounded like, how tall she was, what she and Eddie looked like together.

Gorgeous, obviously. Hot. But did they smile at each other? Did they touch each other easily, his arm around her waist, her hand on his shoulder? Were there furtive caresses, brushings of hands under tables, secret signals only they knew?

There must’ve been. Marriage was like that, even though most of the ones I’d seen hadn’t seemed worth the effort.

So, Bea Rochester had been perfect. The perfect mogul, the perfect woman, the perfect wife. Probably had never even heard of Easy Mac or seen the inside of a pawnshop.

But I had one thing over her. I was still alive.

Eddie isn’t there when I walk Adele the next morning. His car is missing from the garage, and I tell myself I’m not disappointed when I take the puppy from the backyard and out for her walk.

Thornfield Estates is just up the hill from Mountain Brook Village where I used to work, so this morning, I take Adele there, her little legs trotting happily as we turn out of the neighborhood. I tell myself it’s because I’m bored with the same streets, but really, it’s because I want people to see us. I want people who don’t know I’m the dog-walker to see me with Eddie’s dog. Which means, in their heads, I’m linked with Eddie.

It makes me hold my head up higher as I walk past Roasted, past the little boutique selling things that I now recognize as knockoffs of Southern Manors. I pass three stores with brightly patterned quilted bags in the windows, and I think how many of those bags are probably tucked away in closets in Thornfield Estates.