The Phantom Tollbooth

“Help you! You must help yourself,” the dog replied, carefully winding himself with his left hind leg. “I suppose you know why you got stuck.”

“I suppose I just wasn’t thinking,” said Milo.

“PRECISELY,” shouted the dog as his alarm went off again. “Now you know what you must do.”

“I’m afraid I don’t,” admitted Milo, feeling quite stupid.

“Well,” continued the watchdog impatiently, “since you got here by not thinking, it seems reasonable to expect that, in order to get out, you must start thinking.” And with that he hopped into the car.

“Do you mind if I get in? I love car rides.”

Milo began to think as hard as he could (which was very difficult, since he wasn’t used to it). He thought of birds that swim and fish that fly. He thought of yesterday’s lunch and tomorrow’s dinner. He thought of words that began with J and numbers that end in 3. And, as he thought, the wheels began to turn.

“We’re moving, we’re moving,” he shouted happily.

“Keep thinking,” scolded the watchdog.

The little car started to go faster and faster as Milo’s brain whirled with activity, and down the road they went. In a few moments they were out of the Doldrums and back on the main road. All the colours had returned to their original brightness, and as they raced along the road, Milo continued to think of all sorts of things; of the many detours and wrong turns that were so easy to take, of how fine it was to be moving along, and, most of all, how much could be accomplished with just a little thought. And the dog, his nose in the wind, just sat back, watchfully ticking.

Chapter Three WELCOME TO DICTIONOPOLIS

“YOU MUST EXCUSE MY gruff conduct,” the watchdog said, after they’d been driving for some time, “but you see it’s traditional for watchdogs to be ferocious…”

Milo was so relieved at having escaped the Doldrums that he assured the dog that he bore him no ill will and, in fact, was very grateful for the assistance.

“Splendid,” shouted the watchdog, “I’m very pleased – I’m sure we’ll be great friends for the rest of the trip. You may call me Tock.”

“That is a strange name for a dog who goes tickticktickticktick all day,” said Milo. “Why didn’t they call you—”

“Don’t say it,” gasped the dog, and Milo could see a tear well up in his eye.

“I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings,” said Milo, not meaning to hurt his feelings.

“That’s all right,” said the dog, getting hold of himself. “It’s an old story and a sad one, but I can tell it to you now.

“When my brother was born, the first pup in the family, my parents were overjoyed and immediately named him Tick in expectation of the sound they were sure he’d make. On first winding him, they discovered to their horror that, instead of going tickticktickticktick, he went tocktocktocktocktocktock. They rushed to the Hall of Records to change the name, but too late. It had already been officially inscribed, and nothing could be done. When I arrived they were determined not to make the same mistake twice and, since it seemed logical that all their children would make the same sound, they named me Tock. Of course, you know the rest – my brother is called Tick because he goes tocktocktocktocktocktocktock and I am called Tock because I go tickticktickticktickticktick, and both of us are for ever burdened with the wrong names. My parents were so overwrought that they gave up having any more children and devoted their lives to doing good work among the poor and hungry.”

“But how did you become a watchdog?” interjected Milo, hoping to change the subject, as Tock was sobbing quite loudly now.

“That,” he said, rubbing a paw in his eye, “is also traditional. My family have always been watchdogs – from father to son, almost since time began.

“You see,” he continued, beginning to feel better, “once there was no time at all, and people found it very inconvenient. They never knew whether they were eating lunch or dinner, and they were always missing trains. So time was invented to help them keep track of the day and get to places when they should. When they began to count all the time that was available, what with 60 seconds in a minute and 60 minutes in an hour and 24 hours in a day and 365 days in a year, it seemed as if there was much more than could ever be used. ‘If there’s so much of it, it couldn’t be very valuable,’ was the general opinion, and it soon fell into disrepute. People wasted it and even gave it away. Then we were given the job of seeing that no one wasted time again,” he said, sitting up proudly. “It’s hard work but a noble calling. For you see” – and now he was sitting on the seat, one foot on the windscreen, shouting with his arms outstretched – “it is our most valuable possession, more precious than diamonds. It marches on, it and tide wait for no man, and—”

At that point in the speech the car hit a bump in the road and the watchdog collapsed in a heap on the front seat with his alarm again ringing furiously.

“Are you all right?” shouted Milo.

“Umphh,” grunted Tock. “Sorry to get carried away, but I think you get the point.”

As they drove along, Tock continued to explain the importance of time, quoting the old philosophers and poets and illustrating each point with gestures that brought him perilously close to tumbling headlong from the speeding car.

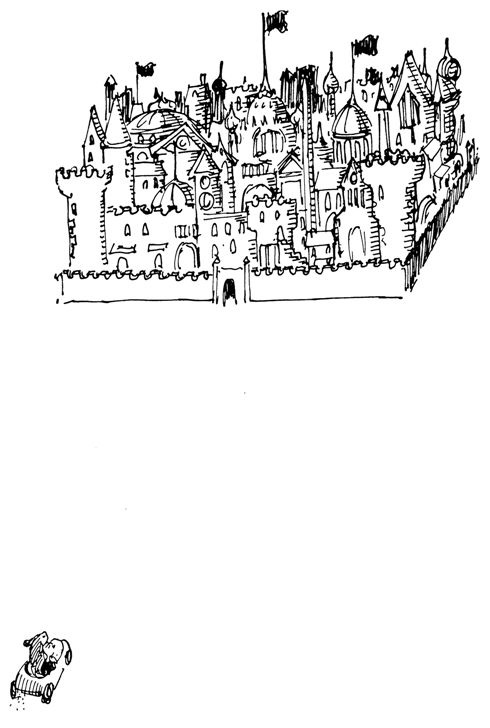

Before long they saw in the distance the towers and flags of Dictionopolis sparkling in the sunshine, and in a few moments they reached the great wall and stood at the gateway to the city.

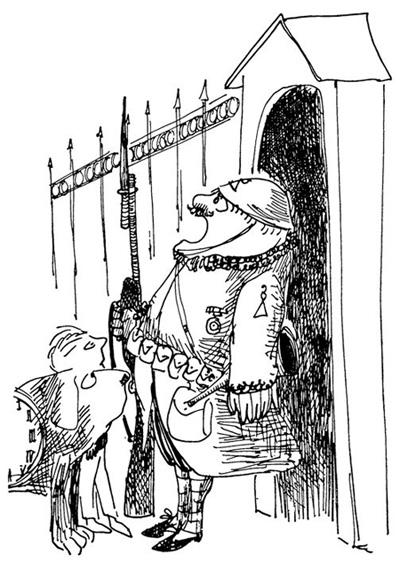

“A-H-H-H-R-R-E-M-M—” roared the sentry, clearing his throat and snapping smartly to attention. “This is Dictionopolis, a happy kingdom, advantageously located in the Foothills of Confusion and caressed by gentle breezes from the Sea of Knowledge. Today, by Royal Proclamation, is market day. Have you come to buy or sell?”

“I beg your pardon?” said Milo.

“Buy or sell, buy or sell,” repeated the sentry impatiently. “Which is it? You must have come for some reason.”

“Well, I—” Milo began.

“Come now, if you don’t have a reason, you must at least have an explanation or certainly an excuse,” interrupted the sentry.

Milo shook his head.

“Very serious, very serious,” the sentry said, shaking his head also. “You can’t get in without a reason.” He thought for a moment, and then continued: “Wait a minute; maybe I have an old one you can use.”

He took a battered suitcase from the sentry box and began to rummage busily through it, mumbling to himself, “No…no…no…this won’t do…no…h-m-m-m…ah, this is fine,” he cried triumphantly, holding up a small medallion on a chain. He dusted it off, and engraved on one side were the words “WHY NOT?”

“That’s a good reason for almost anything – a bit used perhaps, but still quite serviceable.” And with that he placed it round Milo’s neck, pushed back the heavy iron gate, bowed low, and motioned them into the city.

“I wonder what the market will be like,” thought Milo as they drove through the gate; but before there was time for an answer they had driven into an immense square crowded with long lines of stalls heaped with merchandise and decorated in gaily coloured bunting. Overhead a large banner proclaimed:

WELCOME TO THE WORD MARKET

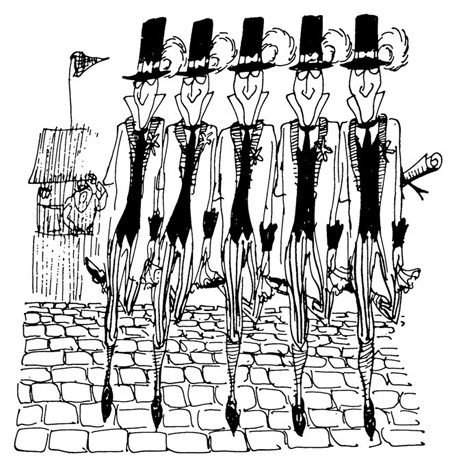

And, from across the square, five very tall, thin gentlemen regally dressed in silks and satins, plumed hats, and buckled shoes rushed up to the car, stopped short, mopped five brows, caught five breaths, unrolled five parchments, and began talking in turn.

“Greetings!”

“Salutations!”

“Welcome!”

“Good afternoon!”

“Hello!”

Milo nodded his head, and they went on, reading from their scrolls.

“By order of Azaz the Unabridged –”

“King of Dictionopolis –”

“Monarch of letters –”

“Emperor of phrases, sentences, and miscellaneous figures of speech –”

“We offer you the hospitality of our kingdom.”

“Country,”

“Nation,”

“State,”

“Commonwealth,”

“Realm,”

“Empire,”

“Palatinate,”

“Principality.”

“Do all those words mean the same thing?” gasped Milo.

“Of course.”

“Certainly.”

“Precisely.”

“Exactly.”

“Yes,” they replied in order.

“Well, then,” said Milo, not understanding why each one said the same thing in a slightly different way, “wouldn’t it be simpler to use just one? It would certainly make more sense.”

“Nonsense.”

“Ridiculous.”

“Fantastic.”

“Absurd.”

“Bosh,” they chorused again, and continued.

“We’re not interested in making sense; it’s not our job,” scolded the first.

“Besides,” explained the second, “one word is as good as another – so why not use them all?”

“Then you don’t have to choose which one is right,” advised the third.

“Besides,” sighed the fourth, “if one is right, then ten are ten times as right.”

“Obviously you don’t know who we are,” sneered the fifth. And they presented themselves one by one as:

“The Duke of Definition.”

“The Minister of Meaning.”

“The Earl of Essence.”

“The Count of Connotation.”

“The Under-secretary of Understanding.”

Milo acknowledged the introduction and, as Tock growled softly, the minister explained.

“We are the king’s advisers, or, in more formal terms, his cabinet.”

“Cabinet,” recited the duke: “(1) a small private room or closet, case with drawers, etc., for keeping valuables or displaying curiosities; (2) council room for chief ministers of state; (3) a body of official advisers to the chief executive of a nation.”

“You see,” continued the minister, bowing thankfully to the duke, “Dictionopolis is the place where all the words in the world come from. They’re grown right here in our orchards.”

“I didn’t know that words grew on trees,” said Milo timidly.

“Where did you think they grew?” shouted the earl irritably. A small crowd began to gather to see the little boy who didn’t know that letters grew on trees.

“I didn’t know they grew at all,” admitted Milo even more timidly. Several people shook their heads sadly.

“Well, money doesn’t grow on trees, does it?” demanded the count.

“I’ve heard not,” said Milo.

“Then something must. Why not words?” exclaimed the under-secretary triumphantly. The crowd cheered his display of logic and continued about its business.

“To continue,” continued the minister impatiently. “Once a week by Royal Proclamation the word market is held here in the great square and people come from everywhere to buy the words they need or trade in the words they haven’t used.”

“Our job,” said the count, “is to see that all the words sold are proper ones, for it wouldn’t do to sell someone a word that had no meaning or didn’t exist at all. For instance, if you bought a word like ghlbtsk, where would you use it?”

“It would be difficult,” thought Milo – but there were so many words that were difficult, and he knew hardly any of them.

“But we never choose which ones to use,” explained the earl as they walked towards the market stalls, “for as long as they mean what they mean to mean we don’t care if they make sense or nonsense.”

“Innocence or magnificence,” added the count.

“Reticence or common sense,” said the under-secretary.

“That seems simple enough,” said Milo, trying to be polite.

“Easy as falling off a log,” cried the earl, falling off a log with a loud thump.

“Must you be so clumsy?” shouted the duke.

“All I said was—” began the earl, rubbing his head.

“We heard you,” said the minister angrily, “and you’ll have to find an expression that’s less dangerous.”

The earl dusted himself, as the others snickered audibly.

“You see,” cautioned the count, “you must pick your words very carefully and be sure to say just what you intend to say. And now, we must leave to make preparations for the Royal Banquet.”

“You’ll be there, of course,” said the minister.

But before Milo had a chance to say anything, they were rushing off across the square as fast as they had come.

“Enjoy yourself in the market,” shouted back the under-secretary.

“Market,” recited the duke: “an open space or covered building in which—”

And that was the last Milo heard as they disappeared into the crowd.

“I never knew words could be so confusing,” Milo said to Tock as he bent down to scratch the dog’s ear.

“Only when you use a lot to say a little,” answered Tock.

Milo thought this was quite the wisest thing he’d heard all day. “Come on,” he shouted, “let’s see the market. It looks very exciting.”

Chapter Four CONFUSION IN THE MARKET PLACE

INDEED IT WAS for, as they approached, Milo could see crowds of people pushing and shouting their way among the stalls, buying and selling, trading and bargaining. Huge wooden-wheeled carts streamed into the market square from the orchards, and long caravans bound for the four corners of the kingdom made ready to leave. Sacks and boxes were piled high waiting to be delivered to the ships that sailed the sea of Knowledge, and off to one side a group of minstrels sang songs to the delight of those either too young or too old to engage in trade. But above all the noise and tumult of the crowd could be heard the merchants’ voices loudly advertising their products.

“Get your fresh-picked ifs, ands, and buts.”

“Hey-yaa, hey-yaa, hey-yaa, nice ripe wheres and whens.”

“Juicy, tempting words for sale.”

So many words and so many people! They were from every place imaginable and some places even beyond that, and they were all busy sorting, choosing, and stuffing things into cases. As soon as one was filled, another was begun. There seemed to be no end to the bustle and activity.

Milo and Tock wandered up and down between the stalls looking at the wonderful assortment of words for sale. There were short ones and easy ones for everyday use, and long and important ones for special occasions, and even some marvellously fancy ones packed in individual gift boxes for use in royal decrees and pronouncements.

“Step right up, step right up – fancy, best-quality words right here,” announced one man in a booming voice. “Step right up – ah, what can I do for you, little boy? How about a nice bagful of pronouns – or maybe you’d like our special assortment of names?”

Milo had never thought much about words before, but these looked so good that he longed to have some.

“Look, Tock,” he cried, “aren’t they wonderful?”

“They’re fine, if you have something to say,” replied Tock in a tired voice, for he was much more interested in finding a bone than in shopping for new words.

“Maybe if I buy some I can learn how to use them,” said Milo eagerly as he began to pick through the words in the stall. Finally, he chose three which looked particularly good to him – “quagmire,” “flabbergast,” and “upholstery”. He had no idea what they meant, but they looked very grand and elegant.

“How much are these?” he enquired, and when the man whispered the answer he quickly put them back on the shelf and started to walk on.

“Why not take a few pounds of ‘happys’?” advised the salesman. “They’re much more practical – and very useful for Happy Birthday, Happy New Year, happy days, and happy-go-lucky.”

“I’d like to very much,” began Milo, “but—”

“Or perhaps you’d be interested in a package of ‘goods’ – always handy for good morning, good afternoon, good evening, and goodbye,” he suggested.

Milo did want to buy something, but the only money he had was the coin he needed to get back through the tollbooth, and Tock, of course, had nothing but the time.

“No, thank you,” replied Milo. “We’re just looking.” And they continued on through the market.

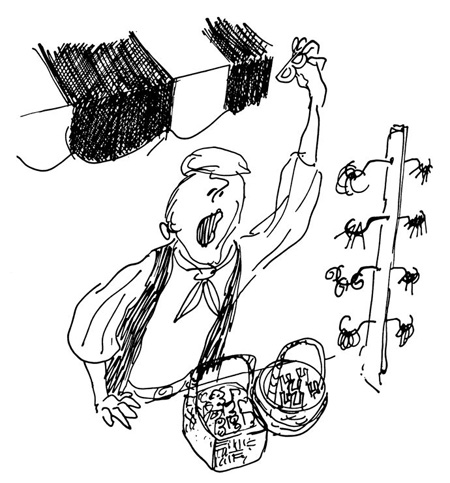

As they turned down the last lane of stalls, Milo noticed a wagon that seemed different from the rest. On its side was a small neatly lettered sign that said DO IT YOURSELF, and inside were twenty-six bins filled with all the letters of the alphabet from A to Z.

“These are for people who like to make their own words,” the man in charge informed him. “You can pick any assortment you like or buy a special box complete with all letters, punctuation marks, and a book of instructions. Here, taste an A; they’re very good.”

Milo nibbled carefully at the letter and discovered that it was quite sweet and delicious – just the way you’d expect an A to taste.

“I knew you’d like it,” laughed the letter man, popping two Gs and an R into his mouth and letting the juice drip down his chin. “As are one of our most popular letters. All of them aren’t so good,” he confided in a low voice. “Take the Z, for instance – very dry and sawdusty. And the X? Why, it tastes like a trunkful of stale air. That’s why people hardly ever use them. But most of the others are quite tasty. Try some more.”

He gave Milo an I, which was icy and refreshing, and Tock a crisp, crunchy C.

“Most people are too lazy to make their own words,” he continued, “but it’s much more fun.”

“Is it difficult? I’m not much good at making words,” admitted Milo, spitting the pips from a P.

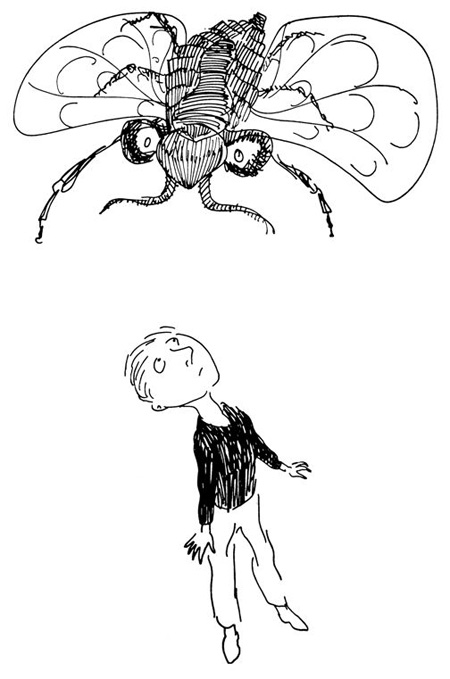

“Perhaps I can be of some assistance – a-s-s-i-s-t-a-n-c-e,” buzzed an unfamiliar voice, and when Milo looked up he saw an enormous bee, at least twice his size, sitting on top of the wagon.

“I am the Spelling Bee,” announced the Spelling Bee. “Don’t be alarmed – a-l-a-r-m-e-d.”

Tock ducked under the wagon, and Milo, who was not over fond of normal-sized bees, began to back away slowly.

“I can spell anything – a-n-y-t-h-i-n-g,” he boasted, testing his wings. “Try me, try me!”

“Can you spell goodbye?” suggested Milo as he continued to back away.

The bee gently lifted himself into the air and circled lazily over Milo’s head.

“Perhaps – p-e-r-h-a-p-s – you are under the misapprehension – m-i-s-a-p-p-r-e-h-e-n-s-i-o-n – that I am dangerous,” he said, turning a smart loop to the left. “Let me assure – a-s-s-u-r-e – you that my intentions are peaceful – p-e-a-c-e-f-u-l.” And with that he settled back on top of the wagon and fanned himself with one wing. “Now,” he panted, “think of the most difficult word you can and I’ll spell it. Hurry up, hurry up!” And he jumped up and down impatiently.

“He looks friendly enough,” thought Milo, not sure just how friendly a friendly bumblebee should be, and tried to think of a very difficult word. “Spell ‘vegetable’,” he suggested, for it was one that always troubled him at school.

“That is a difficult one,” said the bee, winking at the letter man. “Let me see now…hmmmmmm…” He frowned and wiped his brow and paced slowly back and forth on top of the wagon. “How much time do I have?”

“Just ten seconds,” cried Milo excitedly. “Count them off, Tock.”

“Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, oh dear,” the bee repeated, continuing to pace nervously. Then, just as the time ran out, he spelled as fast as he could – “v-e-g-e-t-a-b-l-e”.

“Correct,” shouted the letter man, and everyone cheered.

“Can you spell everything?” asked Milo admiringly.

“Just about,” replied the bee with a hint of pride in his voice. “You see, years ago I was just an ordinary bee minding my own business, smelling flowers all day, and occasionally picking up part-time work in people’s bonnets. Then one day I realized that I’d never amount to anything without an education and, being naturally adept at spelling, I decided that—”

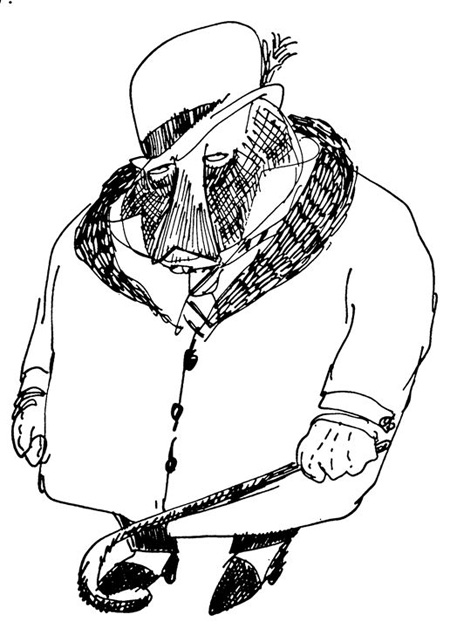

“BALDERDASH!” shouted a booming voice. And from behind the wagon stepped a large beetle-ink insect, dressed in a lavish coat, striped trousers, checked waistcoat, spats, and a derby hat. “Let me repeat – BALDERDASH!” he shouted again, swinging his cane and clicking his heels in mid-air. “Come now, don’t be ill-mannered. Isn’t someone going to introduce me to the little boy?”

“This,” said the bee with complete disdain, “is the Humbug. A very dislikable fellow.”

“NONSENSE! Everyone loves a Humbug,” shouted the Humbug. “As I was saying to the king just the other day—”

“You’ve never met the king,” accused the bee angrily. Then, turning to Milo, he said, “Don’t believe a thing this old fraud says.”

“BOSH!” replied the Humbug. “We’re an old and noble family, honourable to the core – Insecticus Humbugium, if I may use the Latin. Why, we fought in the Crusades with Richard the Lionheart, crossed the Atlantic with Columbus, blazed trails with the pioneers, and today many members of the family hold prominent government positions throughout the world. History is full of Humbugs.”

“A very pretty speech – s-p-e-e-c-h,” sneered the bee. “Now why don’t you go away? I was just advising the lad of the importance of proper spelling.”

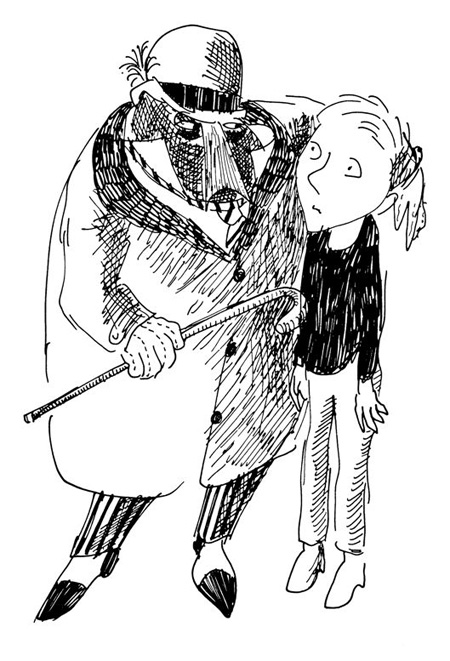

“BAH!” said the bug, putting an arm round Milo. “As soon as you learn to spell one word, they ask you to spell another. You can never catch up – so why bother? Take my advice, my boy, and forget about it. As my great-great-great-grandfather George Washington Humbug used to say—”

“You, sir,” shouted the bee very excitedly, “are an imposter – i-m-p-o-s-t-e-r – who can’t even spell his own name.”

“A slavish concern for the composition of words is the sign of a bankrupt intellect,” roared the Humbug, waving his cane furiously.

Milo didn’t have any idea what this meant, but it seemed to infuriate the Spelling Bee, who flew down and knocked off the Humbug’s hat with his wing.

“Be careful,” shouted Milo as the bug swung his cane again, catching the bee on the foot and knocking over the box of Ws.

“My foot!” shouted the bee.