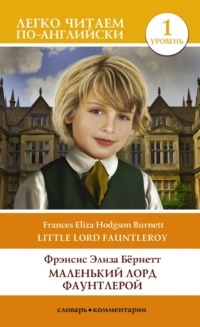

Маленький Лорд Фаунтлерой. Уровень 1 / Little Lord Fauntleroy

“Oh!” she said, “that was very kind of the Earl; Cedric will be so glad! He has always been fond of Bridget and Michael. I have often wished I had been able to help them more. Michael is a hard-working man when he is well, but he has been ill a long time and needs expensive medicines and warm clothing and nourishing food[41]. He and Bridget will not be wasteful of what is given them.”

Mr. Havisham put his thin hand in his breast pocket and drew forth a large pocket-book.

“I do not know that you have realized,” he said, “that the Earl of Dorincourt is an exceedingly rich man. If you will call Lord Fauntleroy back and allow me, I will give him five pounds for these people.”

“That would be twenty-five dollars!” exclaimed Mrs. Errol. “It will seem like wealth to them. I can hardly believe that it is true.”

“It is quite true,” said Mr. Havisham, with a dry smile. “A great change has taken place in your son’s life, a great deal of power will lie in his hands.”

Then his mother went for Cedric and brought him back into the parlor.

His little face looked quite anxious when he came in. He was very sorry for Bridget.

“Dearest said you wanted me,” he said to Mr. Havisham. “I’ve been talking to Bridget.”

Mr. Havisham looked down at him for a moment.

“The Earl of Dorincourt-” he began, and then he glanced involuntarily[42] at Mrs. Errol.

Little Lord Fauntleroy’s mother suddenly kneeled down by him and put both her tender arms around his childish body.

“Ceddie,” she said, “the Earl is your grandpapa, your own papa’s father. He wishes you to be happy and to make other people happy. He told Mr. Havisham so, and gave him a great deal of money for you. You can give some to Bridget now; enough to pay her rent and buy Michael everything. Isn’t that fine, Ceddie? Isn’t he good?” And she kissed the child on his round cheek, where the bright color suddenly flashed up in his excited amazement.

He looked from his mother to Mr. Havisham.

“Can I have it now?” he cried. “Can I give it to her this minute? She’s just going.”

Mr. Havisham handed him the money and Ceddie flew out of the room with it.

“Bridget!” they heard him shout, as he ran into the kitchen. “Bridget, wait a minute! Here’s some money. It’s for you, and you can pay the rent. My grandpapa gave it to me. It’s for you and Michael!”

“Oh, Master Ceddie!” cried Bridget, in an awe-stricken[43] voice. “It’s twenty-five dollars here. Where is the mistress?”

“I think I will have to go and explain it to her,” Mrs. Errol said.

So she, too, went out of the room and Mr. Havisham was left alone for a while.

Cedric and his mother came back soon after. Cedric was in high spirits[44]. He sat down in his own chair, between his mother and the lawyer.

“She cried!” he said. “She said she was crying for joy! I never saw anyone cry for joy before. My grandpapa must be a very good man. I didn’t know he was such a good man. It’s more-more agreeable to be an earl than I thought it was.”

III

In the week before they sailed for England he did many interesting things. The lawyer long after remembered the morning they went down-town together to visit to Dick, and the afternoon they so amazed the apple-woman of ancient lineage by stopping before her stall and telling her she was to have a tent, and a shawl, and a sum of money which seemed to her quite wonderful.

The interview with Dick was quite exciting. Dick had just been having a great deal of trouble with Jake, and was in low spirits when they saw him. Lord Fauntleroy’s manner of announcing the object of his visit was very simple and unceremonious. Mr. Havisham was much impressed by its directness as he stood by and listened. The statement that his old friend had become a lord, and was in danger of being an earl if he lived long enough, caused Dick to open his eyes and mouth.

And the end of the matter was that Dick actually bought Jake out, and found himself the possessor of the business and some new brushes and a most wonderful sign and outfit. He could not believe in his good luck any more easily than the apple-woman of ancient lineage could believe in hers; He hardly seemed to realize anything until Cedric put out his hand to shake hands with him before going away.

“Well, goodbye,” Cedric said; and though he tried to speak confidently, there was a little tremble in his voice and he winked his big brown eyes. “And I hope trade’ll be good. I’m sorry I’m going away to leave you, but perhaps I shall come back again when I’m an earl. And I wish you’d write to me, because we were always good friends. And if you write to me, here’s where you must send your letter.” And he gave him a slip of paper. “And my name isn’t Cedric Errol anymore; it’s Lord Fauntleroy and-and goodbye, Dick.”

Until the day of his departure, his lordship spent as much time as possible with Mr. Hobbs in the store. When his young friend brought to him in triumph the parting gift of a gold watch and chain, Mr. Hobbs found it difficult to acknowledge it properly. He laid the case on his stout knee, and blew his nose violently several times.

“There’s something written on it,” said Cedric, – “inside the case. I told the man myself what to say. ‘From his oldest friend, Lord Fauntleroy, to Mr. Hobbs. When you see this, remember me.’”

Mr. Hobbs blew his nose very loudly again.

“I will not forget you,” he said, speaking a little huskily; “nor don’t you go and forget me when you get among the British aristocracy.”

“I would not forget you, whoever I was among,” answered his lordship. “I’ve spent my happiest hours with you; at least, some of them. I hope you’ll come to see me sometime. I’m sure my grandpapa would be very much pleased.”

“I’d come to see you,” replied Mr. Hobbs.

At last all the preparations were complete; the day came when the trunks were taken to the steamer. It was just at the very last, when someone hurriedly forcing his way through people came toward Cedric. It was a boy, with something red in his hand. It was Dick. He came up to Cedric quite breathless.

“I’ve run all the way,” he said. “I’ve come down to see you. Trade’s been prime! I bought this for you out of what I made yesterday. You can wear it when you get among the swells[45]. It’s a handkerchief.”

He poured it all forth as if in one sentence. A bell rang, and he made a leap away before Cedric had time to speak.

“Goodbye!” he panted. “Wear it when you get among the swells.” And he darted off[46] and was gone.

Cedric held the handkerchief in his hand. It was of bright red silk ornamented with purple horseshoes and horses’ heads.

Little Lord Fauntleroy leaned forward and waved the red handkerchief.

“Goodbye, Dick!” he shouted, lustily. “Thank you! Goodbye, Dick!”

And the big steamer moved away, and the people cheered again, and Cedric’s mother drew the veil over her eyes.

IV

It was during the voyage that Cedric’s mother told him that his home was not to be hers; and when he first understood it, his grief was so great that Mr. Havisham saw that the Earl had been wise in making the arrangements that his mother should be quite near him, and see him often. But his mother managed the little fellow so sweetly and lovingly, and made him feel that she would be so near him, that, after a while, he forgot any fear.

He could not but feel puzzled by such a strange state of affairs, which could put his “Dearest” in one house and himself in another. The fact was that Mrs. Errol had thought it better not to tell him why this plan had been made.

“I prefer he should not be told,” she said to Mr. Havisham. “He would not really understand; he would only be shocked and hurt; and I feel sure that his feeling for the Earl will be a more natural one if he does not know that his grandfather dislikes me so bitterly. It is better for him that he should not be told until he is much older, and it is far better for the Earl. It would make a barrier between them, even though Ceddie is such a child.”

So Cedric only knew that there was some mysterious reason for the arrangement, some reason which he was not old enough to understand, but which would be explained when he was older.

It was eleven days after he had said goodbye to his friend Dick before he reached Liverpool; and it was on the night of the twelfth day that the carriage in which he and his mother and Mr. Havisham had driven from the station stopped before the gates of Court Lodge. Mary had come with them to attend her mistress, and she had reached the house before them. When Cedric jumped out of the carriage he saw one or two servants standing in the wide, bright hall, and Mary stood in the door-way.

Lord Fauntleroy sprang at her with a happy little shout.

“Did you get here, Mary?” he said. “Here’s Mary, Dearest,” and he kissed the maid on her rough red cheek.

“I am glad you are here, Mary,” Mrs. Errol said to her in a low voice. “It is such a comfort to me to see you. It takes the strangeness away.”

Cedric pulled off his overcoat quite as if he were used to doing things for himself, and began to look around him. He looked around the broad hall, at the pictures and stags’ antlers[47] and interesting things that ornamented it. Mary led them upstairs to a bright bedroom where a fire was burning, and a large snow-white Persian cat was sleeping luxuriously on the white fur hearth-rug[48].

“It was the house-keeper up at the Castle, ma’am, sent her to you,” explained Mary. “She is a kind-hearted lady and has had everything done to prepare’ for you. And she said to say the big cat sleeping on the rug might make the room more homelike to you. ”

When they were ready, they went downstairs into another big bright room. The stately white cat had responded to Lord Fauntleroy’s stroking and followed him downstairs, and when he threw himself down upon the rug, she curled herself up grandly beside him as if she intended to make friends. Cedric was so pleased that he put his head down by hers, and lay stroking her, not noticing what his mother and Mr. Havisham were saying.

They were, indeed, speaking in a rather low tone. Mrs. Errol looked a little pale and agitated.

“Does he need to go tonight?” she said. “May he stay with me tonight?”

“Yes,” answered Mr. Havisham in the same low tone; “it will not be necessary for him to go tonight. I myself will go to the Castle as soon as we have dined, and inform the Earl of our arrival.”

Then she looked at the lawyer. “Will you tell him, if you please,” she said, “that I do not want the money?”

“The money!” Mr. Havisham exclaimed. “You can not mean the income he proposed to settle upon you!”

“Yes,” she answered, quite simply; “I think I should rather not have it. I am obliged to accept the house, and I thank him for it, because it makes it possible for me to be near my child; but I have a little money of my own, – enough to live simply upon, – and I should rather not take the other. As he dislikes me so much, I should feel a little as if I were selling Cedric to him. I am giving him up only because I love him enough to forget myself for his good, and because his father would wish it to be so.”

Mr. Havisham rubbed his chin.

“This is very strange,” he said. “He will be very angry. He won’t understand it.”

“I think he will understand it after he thinks it over,” she said. “I do not really need the money, and why should I accept luxuries from the man who hates me so much that he takes my little boy from me-his son’s child?”

Mr. Havisham looked reflective for a few moments.

“I will deliver your message,” he said afterward.

When, later in the evening, Mr. Havisham presented himself at the Castle, he was taken at once to the Earl. He found him sitting by the fire in a luxurious easy-chair, his foot on a gout-stool. He looked at the lawyer sharply from under his shaggy eyebrows, but Mr. Havisham could see that, in spite of his pretense at calmness, he was nervous and secretly excited.

“Well,” he said; “well, Havisham, come back, have you? What’s the news?”

“Lord Fauntleroy and his mother are at Court Lodge,” replied Mr. Havisham. “They bore the voyage very well and are in excellent health.”

The Earl made a half-impatient sound and moved his hand restlessly.

“Glad to hear it,” he said brusquely. “So far, so good. Have a glass of wine and settle down. What else?”

Mr. Havisham drank a little of the glass of port he had poured out for himself, and sat holding it in his hand.

“It is rather difficult to judge of the character of a child of seven,” he said cautiously.

“A fool, is he?” the Earl exclaimed. “Or a clumsy cub? His American blood tells, does it?”

“I do not think it has injured him, my lord,” replied the lawyer in his dry, deliberate[49] fashion. “I don’t know much about children, but I thought him to be rather a fine lad.”

“Healthy and well-grown?” asked my lord.

“Apparently very healthy, and quite well-grown,” replied the lawyer.

“Straight-limbed and well enough to look at?” demanded the Earl.

A very slight smile touched Mr. Havisham’s thin lips.

“Rather a handsome boy, I think, my lord, as boys go,” he said, “though I am hardly a judge, perhaps. But you will find him somewhat different from most English children, I dare say.”

“I haven’t a doubt of that,” snarled the Earl, a twinge of gout seizing him. “A lot of impudent[50] little beggars[51], those American children; I’ve heard that often enough.”

“It is not exactly impudence in his case,” said Mr. Havisham. “I can hardly describe what the difference is. He has lived more with older people than with children, and the difference seems to be a mixture of maturity and childishness.”

“American impudence!” protested the Earl. “I’ve heard of it before. They call it precocity[52] and freedom. Beastly, impudent bad manners; that’s what it is!”

Mr. Havisham drank some more.

“I have a message to deliver from Mrs. Errol,” he remarked.

“I don’t want any of her messages!” growled his lordship; “the less I hear of her the better.”

“This is a rather important one,” explained the lawyer. “She prefers not to accept the income you proposed to settle on her. She says it is not necessary, and that as the relations between you are not friendly-”

“Not friendly!” exclaimed my lord savagely; “I should say they were not friendly! I hate to think of her! A mercenary, sharp-voiced American! I don’t wish to see her.”

“My lord,” said Mr. Havisham, “you can hardly call her mercenary. She has asked for nothing. She does not accept the money you offer her.”

“All done for effect!” snapped his noble lordship. “She wants to trick me into seeing her. She thinks I will admire her spirit. I don’t admire it! I won’t have her living like a beggar at my park gates. As she’s the boy’s mother, she has a position to keep up, and she will keep it up. She will have the money, whether she likes it or not!”

“She won’t spend it,” said Mr. Havisham.

“I don’t care whether she spends it or not!” blustered my lord. “She will have it sent to her. She will not tell people that she has to live like a beggar because I have done nothing for her! She wants to give the boy a bad opinion of me! I suppose she has poisoned his mind against me already!”

“No,” said Mr. Havisham. “I have another message, which will prove to you that she has not done that.”

“I don’t want to hear it!” panted the Earl, out of breath with anger and excitement and gout.

But Mr. Havisham delivered it.

“She asks you not to let Lord Fauntleroy hear anything which would lead him to understand that you separate him from her because of your prejudice against her. She says he will not understand it, and it might make him fear you in some measure, or at least cause him to feel less affection for you. She has told him that he is too young to understand the reason, but will hear it when he is older. She wishes that there should be no shadow on your first meeting.”

The Earl sank back into his chair. His deep-set fierce old eyes gleamed under his brows.

“Come, now!” he said, still breathlessly. “Come, now! You don’t mean the mother hasn’t told him?”

“Not one word, my lord,” replied the lawyer calmly. “That I can assure you. The child is prepared to believe you to be the most friendly and loving of grandparents. Nothing-absolutely nothing has been said to him to give him the slightest doubt of your perfection. And as I carried out your commands in every detail, while in New York, he certainly regards you as a wonder of generosity.”

“He does, eh?” said the Earl.

“I give you my word of honor,” said Mr. Havisham, “that Lord Fauntleroy’s impressions of you will depend entirely upon yourself. And if you will pardon the liberty I take in making the suggestion, I think you will succeed better with him if you take the precaution not to speak badly of his mother.”

V

It was late in the afternoon when the carriage with little Lord Fauntleroy and Mr. Havisham drove up the long road which led to the castle.

When the carriage reached the great gates of the park, Cedric looked out of the window to get a good view of the huge stone lions ornamenting the entrance. The gates were opened by a motherly, rosy-looking woman, who came out of a pretty lodge.

The carriage rolled on and on between the great, beautiful trees which grew on each side of the road and stretched their broad, swaying branches in an arch across it. Cedric had never seen such trees, – they were so grand and stately, and their branches grew so low down. Every few minutes he saw something new to wonder at and admire. When he caught sight of the deer, some couched in the grass, some standing with their pretty antlered heads turned toward the road as the carriage wheels disturbed them, he was enchanted.

It was not long after this that they saw the castle. It stood up before them stately and beautiful and gray, the last rays of the sun casting dazzling lights on its many windows. Cedric saw the great entrance-door thrown open and many servants standing in two lines looking at him. He wondered why they were standing there. He did not know that they were there to do honor to the little boy to whom all of this would one day belong. At the head of the line of servants there stood an elderly woman in a rich, plain black silk gown; she had gray hair and wore a cap. As he entered the hall she stood nearer than the rest, and the child thought from the look in her eyes that she was going to speak to him. Mr. Havisham, who held his hand, paused for a moment.

“This is Lord Fauntleroy, Mrs. Mellon,” he said. “Lord Fauntleroy, this is Mrs. Mellon, who is the housekeeper.”

Cedric gave her his hand, his eyes lighting up.

“Was it you who sent the cat?” he said. “I’m much obliged to you, ma’am.”

Mrs. Mellon’s handsome old face looked as pleased as the face of the lodge-keeper’s wife had done. She smiled down on him.

“The cat left two beautiful kittens here,” she said; “they will be sent up to your lordship’s nursery.”

Mr. Havisham said a few words to her in a low voice.

“In the library, sir,” Mrs. Mellon replied. “His lordship is to be taken there alone.”

A few minutes later, the very tall footman, who had escorted Cedric to the library door, opened it and announced: “Lord Fauntleroy, my lord,” in quite a majestic tone.

Cedric walked into the room. It was a very large and wonderful room, with massive carven furniture in it, and shelves upon shelves of books. For a moment Cedric thought there was nobody in the room, but soon he saw that by the fire burning on the wide hearth there was a large easy-chair and that in that chair someone was sitting-someone who did not at first turn to look at him.

But he had attracted attention in one quarter at least. On the floor, by the armchair, lay a dog, a huge tawny mastiff, with body and limbs almost as big as a lion’s; and this great creature stood up majestically and slowly, and marched toward the little fellow with a heavy step.

Then the person in the chair spoke. “Dougal,” he called, “come back, sir.”

But there was no more fear in little Lord Fauntleroy’s heart than there was unkindness-he had been a brave little fellow all his life. He put his hand on the big dog’s collar in the most natural way in the world, and they strayed forward together, Dougal sniffing as he went.

And then the Earl looked up. What Cedric saw was a large old man with shaggy white hair and eyebrows, and a nose like an eagle’s beak[53] between his deep, fierce eyes. There was a sudden glow of triumph in the fiery old Earl’s heart as he saw what a strong, beautiful boy this grandson was, and how unhesitatingly he looked up as he stood with his hand on the big dog’s neck.

Cedric looked at him just as he had looked at the woman at the lodge and at the housekeeper, and came quite close to him.

“Are you the Earl?” he said. “I’m your grandson, you know, that Mr. Havisham brought. I’m Lord Fauntleroy.”

He held out his hand because he thought it must be the polite and proper thing to do even with earls. “I hope you are very well,” he continued, with extreme friendliness. “I’m very glad to see you.”

The Earl shook hands with him, with an interesting gleam in his eyes; just at first, he was so astonished[54] that he hardly knew what to say.

There was a chair near him, and Cedric sat down on it.

“I’ve kept wondering what you would look like,” he remarked. “I used to lie in my bed on the ship and wonder if you would be anything like my father.”

“Am I?” asked the Earl.

“Well,” Cedric replied, “I was very young when he died, and I may not remember exactly how he looked, but I don’t think you are like him.”

“You are disappointed, I suppose?” suggested his grandfather.

“Oh, no,” responded Cedric politely. “Of course you would like anyone to look like your father; but of course you would enjoy the way your grandfather looked, even if he wasn’t like your father. You know how it is yourself about admiring your relations.”

The Earl leaned back in his chair and stared.

“Any boy would love his grandfather,” continued Lord Fauntleroy, “especially one that had been as kind to him as you have been.”

Another strange gleam came into the old nobleman’s eyes.

“Oh!” he said, “I have been kind to you, have I?”

“Yes,” answered Lord Fauntleroy brightly; “I’m ever so much obliged to you about Bridget, and the apple-woman, and Dick.”

“Bridget!” exclaimed the Earl. “Dick! The apple-woman!”

“Yes!” explained Cedric; “the ones you gave me all that money for-the money you told Mr. Havisham to give me if I wanted it.”

“Ha!” exclaimed his lordship. “That’s it, is it? The money you were to spend as you liked. What did you buy with it? I would like to hear something about that.”

“Oh!” said Lord Fauntleroy, “perhaps you didn’t know about Dick and the apple-woman and Bridget. I forgot you lived such a long way off from them. They were particular friends of mine. And you see Michael had the fever-”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

knew nothing about it all – ничего об этом не знал

2

dimples – ямочки на щеках

3

we have no one left but each other – у нас с тобой больше никого нет

4

brought them the ill-will – навлек на них неприязнь

5

nobleman – дворянин, аристократ.

6

to inherit – наследовать

7

heir – наследник

8

Nature had given gifts – природа одарила талантами