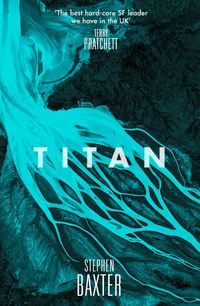

Titan

Lamb released the tethers which still clipped her to the payload bay slide wires, and reached around her. ‘Captive latches released.’

‘Copy.’

He shoved her gently in the back, and she floated away from the bulkhead. ‘Don’t even think about it,’ he said calmly. ‘It’s just like the sims.’

… Suddenly she didn’t have hold of anything, and she was falling.

‘Oh, shit.’

‘We didn’t copy that, EV2,’ the capcom said humourlessly.

Lamb ignored him. ‘Come on, Paula. Turn around.’

She had two big nitrogen-filled fuel tanks on her back now, and there were twenty-four small reaction control system nozzles. She grasped her right-hand controller, and pushed it left. There was a soft tone in her helmet as the thruster worked; she saw a faint sparkle of nitrogen crystals, to her right. In response to the thrust, she tipped a little to the left.

The controller was intuitive; moving it up or down made her pitch, her feet tipping up; left or right gave her a yaw, a sideways tilt. She twisted the handle, and made herself roll about an axis through her head to her feet.

The payload bay rotated around her.

‘It’s heavy,’ she said. ‘I can feel the unit’s inertia as I roll.’

‘You mass more than seven hundred pounds, suit and all, Paula.’

She blipped the RCS thrusters again, and slowed her roll. She finished up facing Lamb, where he clung to the aft cabin bulkhead. She pushed her left-hand controller, which drove her forward and back. There was a gentle shove, and her drifting slowed.

The MMU seemed to be working well, but its scuffs and scorch marks showed its age. And things most definitely did not feel the same, up here, as in the tethered sims on the ground. When she started moving, she just kept on going, until she stopped herself. She was in a frictionless, three-dimensional environment, like a huge ice-rink, where Newton’s laws held sway in their bare simplicity.

No wonder the Station assembly has proceeded so slowly, she thought. We just aren’t evolved for this environment.

‘Okay, Paula,’ Lamb called. ‘You ready for your one small step?’

No, she thought.

‘Let’s do it.’

‘Houston, EV2 is preparing to leave the payload bay.’

‘We copy, Tom.’

Benacerraf tipped herself up so she was facing Earth, with the orbiter behind her.

Earth, before her, was immense, overwhelming. The overall impression was of blue sea and white clouds, the white of an intensity that hurt her eyes. When she looked towards the horizon she could see the atmosphere, a thin blue shell around the planet.

She gave herself a single, firm thrust with the RCS. She felt a small, definite shove in the small of her back.

She rose out of the bay towards the face of Earth; she saw the big silvered doors to either side of her recede.

A tone sounded softly in her helmet, startling her.

‘Oh-two alarm, EV2.,’ the capcom reported.

An oxygen leak. Holed fabric, maybe. ‘Houston, EV2.. Should I come back? I—’

‘Belay that, EV2,’ Lamb said. ‘Paula, just take a couple of deep breaths. Relax. You’re safe and snug in there.’

She became aware of her breathing, which was shallow and rapid. Her suit monitors had misinterpreted her high oxygen consumption as a leak.

Deliberately, she slowed her breathing; she tried to unclench her muscles, to relax in the warm cocoon of the suit.

‘Just look at the view, kid.’

She looked at the view.

She was flying up towards Africa. The clouds piled over the equator seemed to reach down towards her, clearly three-dimensional and casting long shadows. She could see the Nile, and the ribbon development along it, surrounded by the baked-hard surface of the desert; the dependence of the people on the Nile’s water was clear.

She was extraordinarily comfortable. The suit was quiet, warm, safe. She could hear the whir of her backpack’s twenty-thousand rpm fan – it sounded like a pc fan. She heard squeaks and pops on the radio, as she drifted over UHF stations on the ground. In her bubble helmet she had a hundred and eighty degree vision, and she had a great sense of freedom. She knew that when she returned to the cabin, after the EVA, it would seem constricting, absurdly confining.

As she gazed at Earth – at all of humanity, save for the six on orbit with her on Columbia and a handful on Station – she felt some of the tension drain out of her, as if it was being drawn up to the planet. She felt lifted out of the web of concerns that dominated her life: the difficulties of her career, the frustrating pace of the space program, her unsatisfactory relationship with Jackie, her daughter, the blizzard of hassles that made up every day, mail and balky technology and her car and her apartment and accounts she had to pay and …

No wonder people get hooked on this, she thought.

‘Okay, EV2, Houston. Coming up to your three hundred feet limit.’

‘Copy that.’ Three hundred feet was as far as she could allow herself to travel. Moving away from Columbia, Benacerraf was actually entering a slightly different orbit. If she went much further, return to the orbiter would become a full-scale rendezvous, a matter of complex course correction manoeuvres.

She passed out of the shadow of the wing, and into sunlight; her EMU seemed to glow.

‘I see your light, Paula,’ Lamb called.

‘I’m pleased to hear it, Tom.’

‘EV2, Houston. Confirming your ground-to-MMU direct link is operational.’

‘Thank you.’

‘And your transponder beacon is functioning.’

‘Copy that.’

‘EV2, Houston. You have a lot of green-eyed people watching you; looks like you’re having a lot of fun.’

‘Sure. This is working very nicely. Ah, I’m glad I’ve got old Brer Rabbit out here with me, out in the briar patch where he belongs.’

She heard Lamb chuckle at that, back in the payload bay. She was aping the first words he’d spoken on the Moon.

Most astronauts got off the active list after four or five flights. They moved out into industry, or up into some kind of program management position within NASA. What kind of man was it who would keep on subjecting himself – and his family – to the grind of training, two years for every Shuttle mission, the enormous dangers of the missions themselves, flight after flight, year after year, logging up the spaceflight hours well into his sixties, endlessly defying the survival odds?

She’d even formulated the thought that maybe Lamb wasn’t actually good for anything else. To stay in the office you had to resist promotion, after all. You had to demonstrate sustained mediocrity. John Young, the other great surviving Moonwalker, had been taken off the active roster when he’d been so vocal in criticizing NASA safety procedures after Challenger.

Besides, all that ancient astronaut-as-Cold Warrior garbage from the 1960s, which still clung around NASA, just did not cut any ice with Benacerraf. It had nothing to do with the future of space travel as she saw it, which could only be about a steady, logical and gradual expansion of the space frontier, beyond Earth. Or even with the actions required of NASA, the space agency, to survive in a future of decreasing funding, increasing irrationality, a growing sense of military threat from China and elsewhere which was causing the ancient Cold Warriors to come rearing from their bunkers once more …

It might take all of her career to build the Space Station; she might never get to see another human being walk on the Moon. Well, that was fine by her. Space was a damn difficult place to work.

But as long as Lamb, and one or two others, still hung around, you still had the hero-centered distortion of the whole organization. As if everything that had happened after 1972 had been a long, dull coda. Even the Mission Controllers and their backroom staff were mostly aviation people of some kind, she was finding; and a startling number of the controllers – who were supposed to be there as specialist engineers or scientists – would apply to join the astronaut office at every recruitment round, regular as clockwork.

… But all that was before she’d begun to train with Lamb for this flight, STS-143. Before she’d sat with him through hours of sims, observed his prowess at the antique complexities of the Shuttle system, seen him demonstrate his calm control in the abort options. Tom Lamb could handle things, she’d come to realize. His old-fashioned jock bull hid a central, deep-rooted competence.

As she’d been strapped into Columbia’s flight deck for her first launch, she’d been grateful for Lamb’s calm voice, responding to the ground. If anyone could get her home alive, it would be Tom Lamb.

And anyhow, now she was up here, she started to see his point of view.

She swung herself around, and faced back down into the payload bay. She blipped her left-hand controller to slow her rotation.

Columbia’s cabin was above her head, the tail section below her feet. The starboard wing was in the shadow of the sun; the big Stars and Stripes on the port wing was obscured by the open bay doors. Her eyes were dark-adapted to Earthlight, so she could see no stars beyond the orbiter. Columbia was like a complex toy, brilliant white and silver, set against complete blackness.

At first glance Columbia looked faintly ridiculous: that fat, boxy body, the patchy coloration of the thermal protection system, the snub nose, those thick wings and that huge tail: Columbia was like an airliner stranded in space, its aerodynamic surfaces useless in vacuum. Columbia, the first of the five Shuttle orbiters built – and so the most primitive – weighed all of a hundred and eighty thousand pounds dry. You had to haul all that mass up into orbit, and back down again, every flight, to deliver just fifty thousand pounds of payload to orbit.

And after thirty flights Columbia was showing her age. She could see how the white-painted hull was scarred and battered, the slight discolorations between the tiles, the scuffs on the windows that sparkled in the sunlight, the stains on the thermal fabric lining the payload bay.

But all of that seemed to fade from her awareness, as she saw the orbiter drifting serenely against the blackness of space. Bizarrely, Columbia looked as if she belonged up here.

The Shuttle system was the technology of the 1970s, still flying in the ’oos, with the hard wisdom of the intervening years built into it. And, realistically, no replacement system in sight. Columbia was fresh paint over rusty, obsolescent technology. But somehow, up here, she was able to make out the 1960s von Braun dream of spaceplanes which the orbiter embodied.

Her throat hurt. Damn it, she felt as if she was going to cry.

The light around her changed. The shadow of the starboard wing was growing longer. Columbia was passing into another forty-five minute night.

‘… Hey, Paula,’ Tom Lamb said now. ‘Scuttlebutt from home. Some double-dome from JPL is saying he’s found life on Titan.’

‘Really?’

‘So they say. Nice place to hear about it, huh.’

‘Yes,’ she said.

… She turned again, to face Earth.

At the rim of the planet she could see the airglow layer, a bright layer of oxygen radiating at the top of the atmosphere, like a false horizon. The lights of cities, strung along the coasts of the land, looked like streetlights scattered along a road. There was a thunderstorm over central Africa, and she could see lightning sparking constantly, over cloud systems spanning thousands of miles. The lightning propagated through the clouds like a living thing, growing and spreading; its glow shone from beneath the layer of cloud, and she could see three-dimensional structure within the cloud, edges and swirls of purple.

The leading edges of Columbia glowed, a faint orange, in an aura a few inches thick. The glow came from a thin hail of atoms of atomic oxygen, interacting with the orbiter’s surfaces.

Even here, she thought, they were not truly free of Earth.

She thought about the news from Titan, wondering vaguely what it might mean for her.

The low-level arc floodlights in the payload bay glowed like a captive constellation.

The suit technician removed the protective cover from Jiang Ling’s helmet. Jiang sat down on the lip of the hatch and hauled herself into the orbital module, head first. Another technician pulled off her outer boots, and she swung her legs inside the module.

She was alone, here in this orbital compartment, this elongated sphere within which she would spend a week in low Earth orbit. The compartment was like a miniature space station, crammed with storage lockers, provisions, scientific equipment and literature. Everything was gleaming white, new and shiny.

The technicians were framed in the hatchway. They were both Han Chinese: military officers, with their brown uniforms visible under their white coats. They grinned at her. But, she thought, their eyes were hard.

One of them passed her a small brass bell. She took it in her gloved hand. It was inscribed with the face of Mao Zedong, in comfortable, corpulent middle age.

The technician grinned at her. ‘Maybe ta laorenjia will bring you luck.’

She raised her hand in thanks.

The technicians stepped back into the white room beyond the doorway, and hauled the hatch closed. It shut with finality. Even the quality of the sound changed. She was aware of a sense of enclosure, almost of claustrophobia.

Clutching the brass bell, she put such thoughts aside as irrelevant.

Beneath her was an inner hatch. She twisted around and lowered herself through this. Now she was entering the second of her craft’s three modules, called the command compartment, which she would ride to orbit – and home to Earth again, to her planned soft landing in the Gobi Desert.

Below her, inaccessible now, was the third part of her craft: an equipment module, containing fuel tanks, oxygen, water supplies, life support, and the mass of equipment that ran the on-board systems. The equipment module would be used to manoeuvre the craft in orbit, and when Jiang finally returned to Earth this stage would be used as a retro-rocket, before being jettisoned along with the orbital module.

She settled into her couch. The command compartment was a compact half-sphere, its walls curving up before her. There were bulky compartments and packs all around her, strapped to the walls and floor, most of them containing equipment that would be needed for the return to Earth: parachutes, flotation gear, emergency rations, blankets and thick clothes. The spacecraft’s main controls were set out before her: an artificial horizon, handsets for attitude controls, communications and monitoring gear.

She was hemmed in, embedded in this solid mass of equipment like a wrapped-up porcelain doll.

The astronaut trainees, morbidly, called the command compartment the xiaohao, after the small isolation cells which were still operated within Qincheng Prison in Beijing. But her brief feeling of confinement had passed, for the capsule was already alive: the cabin floodlights glowed cheerfully, complex graphics scrolled through the softscreens embedded in the walls, and green lights shone all over the instrument panels.

There were two small circular windows, one to either side of her. Now there was only darkness within them, because the spacecraft – perched here a hundred and seventy feet above the ground at the tip of the Long March booster – was enclosed within its protective fairing. But there was a small periscope, its eyepiece set in the center of the instrument panel before her, whose extension poked out beyond the fairing.

Seen through the periscope, the sky was a vast blue dome, devoid of moisture.

This was Inner Mongolia, the north-east of China. The desert was a vast, tan brown expanse, as flat as a table-top, stretching to the horizon in every direction. Beijing was hundreds of miles east of here. To the north, beyond the shadow of the Great Wall, camel trains still worked across the Mongolian Gobi.

The Jiuquan launch center itself was modest. There were just three launch pads set in a rough triangle a few hundred yards apart. The pads were concrete tables, a hundred feet across, with minimal equipment at each; there was a single gantry almost as tall as the Long March booster itself, which was moved on rails between the pads. She could see the railway spurs which brought booster stages here. There was no surrounding industrial complex, as at Cape Canaveral or Tyuratam. There was only an igloo-like blockhouse close to each pad, buried partly underground, containing the firing rooms; further away there were gleaming tanks and snaking pipelines for propellant storage and delivery, and a small power station.

The launch complex, in fact, was dwarfed by the thousand-mile hugeness of the Gobi.

To Jiang, the elemental simplicity of this facility was its power. Here in the mouth of the desert it was as if her booster had barely any connection with the Earth it was soon to shake off. To Jiang, Jiuquan was the reality of spaceflight, reduced to its core …

The flight was still to come, of course. But already, she sensed, the worst of her mission was over: the public tours, the attention from TV and net correspondents, the speeches to thousands of Party cadres in Tiananmen Square, even the meeting with the Great Helmsman himself. Of course there would be many more such chores after the flight, but that was far from her mind.

For now she was alone in here, contained within the xiaohao – in this environment she had come to know so well. Here, she was in command, and she was ready to confront destiny: to become the first Chinese, in five thousand years of history, to break the bonds of Earth itself.

A voice crackled in the small speakers on her headset. ‘Lei Feng Number One from the firing room. Are you ready to begin your checklist?’

She was still clutching the brass bell. She reached up, and fixed it to the handle of the hatch above her with a twist of wire. She touched Mao’s face with a spacesuited finger. The bell rang gently. She smiled. Now, ta laorenjia could protect her as he did millions of Chinese; Mao Zedong, three decades after his death, had become the most popular household folk god.

She settled back in her couch. ‘This is Jiang Ling in Lei Feng Number One. Yes, I can confirm I am ready to proceed with the checklist. Today is a good day to fly!’

The work seemed to come in waves, with clusters of switches to throw and settings to check in a short time. In addition she had to record measurements in her log book. And she had to work to reduce the condensation inside the cramped compartment. In orbit this would be done automatically, but on the ground the light pumps were overwhelmed by Earth’s gravity, and she had to open and close valves at set times, and she had a little hand-pump she used to move condensate from one part of the cabin to another.

There were several long holds in the countdown, when malfunctions were encountered. During these periods she had literally nothing to do, and she found them difficult times.

She was aware of continual movement and noise. She could feel the rocket swaying as the thin desert wind hit its flanks; and there was a succession of thumps, bangs and shudders, as ancillary equipment was moved to and from the booster. She was very aware that she was suspended at the top of a thin, fragile steel tower housing thousands of tons of highly explosive propellant.

There were cameras all over the cabin, focused on her face behind its open visor, their black lenses glinting in the floods. She tried to keep her expression clear, her movements calm and assured.

She felt a deep nervousness gnaw at her, more worrying even than the prospect that some catastrophe might claim her life, today. If something went wrong, if the mission was aborted, was it possible that she would somehow be blamed?

Jiang was not Han Chinese. She was a Turkic Uighur, a Muslim minority which emanated from the westernmost province of Xinjiang. Jiang’s family came from the desert capital Urumqi; her family had moved to Beijing when she was a child when Jiang’s father, a mid-ranking Party cadre, was posted to the Minorities Institute in the capital in the 1970s. Since her father was both an official and a Uighur, the family had been treated with a special deference reserved for select representatives of minority groups who served as symbols for the Party’s efforts to build ‘socialist solidarity’ between central China and the non-Han regions. In Beijing, Jiang had attended a special ‘experimental’ school reserved for the children of the Party élite.

Among the Han astronaut trainees there had been some resentment at her promotion – sometimes suppressed, sometimes not. And there had been genuine surprise when she had been selected for the honour of this first flight, ahead of the Han candidates.

Jiang believed that it was on the basis of her superior abilities. Perhaps that was true. But she knew that she could not help but accrue rivals and enemies, now, as she moved into national, even international prominence.

Meanwhile the xiaodao xiaoxi – the back-alley scuttlebutt – was that the Chinese space program, in its thirty-year history, had already killed five hundred people. Even worse, it was said, one astronaut had already lost his – or her – life, in a clandestine suborbital test of the Lei Feng-Long March system.

Jiang Ling believed some of this, but not all. She would be a fool to try to deny that she was exposing herself to enormous risks, here in the Lei Feng. Perhaps more risks than any other astronaut from East or West since the first pioneers themselves.

But for Jiang it was worth it. And not for the glory – for being what the People’s Daily called a jianghu haojie, a modern-day knight errant – and certainly not for the ‘iron rice bowl’ which her status afforded her. To Jiang, it was simply this moment, the hours and days to come: to be thrust into orbit, to look down on the Earth like a glowing carpet below. To Jiang, that was worth any risk.

As she’d come to the pad, a technician had told her the Americans were claiming to have found life on Titan, moon of Saturn.

Lying here now, Jiang tried to absorb the news. What could it mean? Could it be true?

In the end she dismissed the speculation. What value was a mission to Saturn? What use was life on Titan, even if it existed? Perhaps the stars were for America, but Earth was for China.

And now the holds started to clear up, and her mood lifted.

Jackie Benacerraf didn’t know what to expect of JPL. She certainly didn’t rely on the descriptions from her mother, the famous spacewoman.

She drove her hired car out along the Glendale Freeway, out of downtown LA, along tree-lined roads. She drove through swank suburbs, following the softscreen map in the car, and was surprised when she rounded a turn, and came upon JPL.

At first glance JPL could have been any reasonably modern corporate or college site, maybe a hospital: it was spread over two hundred acres, nestling in the eroded, green-clad shoulders of the San Gabriel Mountains, the blocky office buildings interspersed with Southern California palms. She caught glimpses of some kind of campus inside the security fences, fountains and trees.

But the roads here were called Mariner Road, and Surveyor Road, and Ranger Road. For the Jet Propulsion Laboratory had built and run spacecraft which had reached every planet in the Solar System, save only Pluto. And, right now, the scientists here were gathering information from the moons of Saturn.

She parked her car. Isaac Rosenberg was there to meet her at the visitors’ reception. ‘Jackie. Thanks for coming in.’

‘Isaac, it’s good to meet you again.’

He pushed his John Lennon spectacles a little further back up his nose. ‘Rosenberg. Everybody calls me Rosenberg.’

‘Rosenberg, then.’

He was somewhere in his mid-twenties, she figured, maybe a couple of years older than she was. He didn’t look as if he lived too well; his face was pale and badly shaved, and his prematurely thinning black hair, none too clean, was tied back in a pony tail.