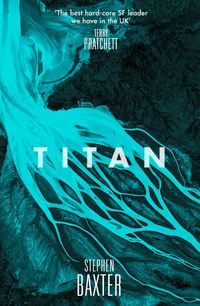

Titan

But none of that mattered, compared to the look in his brown eyes.

He said, ‘Thanks for coming out. Listen, you want me to get you a coffee? A doughnut, maybe?’

‘No, thanks, Rosenberg. I want you to tell me about your results. At the party the other night, you were so –’

‘Out of it.’

‘Were you serious? Are the press reports true? How come the official spokesmen won’t answer questions on it?’

‘Come see the results for yourself.’

He led her through the reception area and across the campus, to a long, low building he called the SFOF, for Space Flight Operations Facility. He took her up to the second floor, to a big windowless loft of a room, painted grey, with grey carpeting. It was divided up into rows of cubicles, within which worked – Rosenberg said – the engineers and scientists who controlled Cassini’s systems. So this is a spacecraft control center, she thought. It was about as lively as a bank’s back office.

They crossed the engineering room, and then passed through a hall to a science area, and entered a new warren of cubicles, the science back room. Rosenberg took her to his own cubicle, which was cluttered up with papers and rolled-up softscreens and an old-fashioned hard-key calculator. There were reproductions of the covers of antique science fiction magazines taped to the cubicle walls, she saw: By Spaceship to Saturn, and Raiders of Saturn’s Rings, and Missing Men of Saturn.

He showed her a Packard Bell softscreen, stuck to one wall, which was cycling through displays of what turned out to be a thermal profile through Titan’s atmosphere, as sampled by the descending Huygens lander. Grabbing a mouse, he cleared down the screen and pulled up data from a fresh database.

She’d met him a few days before at a party at her old fraternity at Caltech, where he was getting steadily drunk on ice beer and talking too much, loud and fast and humourlessly, about his work here at JPL on the Cassini/Huygens mission. He’d attracted a rotating audience of student types, some intrigued, some argumentative; as the group cycled, Rosenberg would happily launch into his obsessive monologue again, as far as Jackie could tell pretty much from the beginning.

He was talking about biochemistry – the chemistry of life – on Saturn’s moon, Titan.

Jackie was intrigued. Here was a classic loser magnet, but with a story of such compelling intensity that it was attracting a crowd, if a transient one. And she got even more interested, when the sensational claims about life on Titan had started appearing in the press and the net.

She was in the middle of a new effort to revive her once-promising career in journalism, which had been pretty much dormant since her second kid was born. If she was going to progress, she knew, she was going to have to develop a nose for a story, her own story, something dramatic and compelling – but out of the way, far from the attention span of the big boys.

And maybe – she’d thought, listening to this skinny monomaniac mouthing off to a bunch of strangers about weird chemistry results from Titan, and with his eyes shining – maybe, she’d found it.

Before the end of that party she’d buttonholed Rosenberg and arranged to meet him here, at JPL. She’d figured it was a better than evens chance that he would have forgotten all about her, in which case she would have driven all this way out here to the arroyo for nothing. But when she’d arrived at the security gate, she found he’d left a media pass for her to collect.

Soon the softscreen was covered by chemical notation and complex molecular structure charts.

He said, ‘How much biochemistry do you know?’

Actually, she’d picked up a little in her graduate days. But she said, ‘Nothing.’

‘All right. I’m working in the group responsible for the GCMS results.’

‘GCMS?’

‘Gas chromatograph and mass spectrometer. In-situ measurements of the chemical composition of gases and aerosols in Titan’s atmosphere, and at the end of Huygens’s descent, a direct sample of the surface. The lead scientist is a guy at Goddard. On the lander, a slug sample was drawn in through filters and into an oven furnace, which –’

‘Enough. Tell me what you do.’

‘I’m working on high atomic number results. Complex molecules. Look – what do you know about conditions on the surface of Titan?’

‘Only what I’ve seen in the pop press the last few weeks.’

‘All right. Titan is an ice moon, with a thick layer of atmosphere. The only moon with a significant layer of air, anywhere. In a lot of ways, Titan right now is like primeval Earth – say, four and a half billion years ago. Its chemistry is mostly based around carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen. And chemistry like that produces a lot of the key molecules of prebiotic chemistry.’

‘Prebiotic?’

‘The components of life. But there’s a crucial difference. Titan has no liquid water. It’s too cold for that. The importance of water on primitive Earth is that it was a solvent. It allowed the polymerization of volatile reactive organics and the hydrolysis of prebiotic oligomers into biomolecules … I’m sorry. Look, you need water as a solution medium, so that the components, the building blocks, can assemble themselves into proteins and nucleic acids, the main macromolecules of our form of life.’

Our form of life. That phrase made her shiver. ‘But maybe there are other solvents.’

‘Correct. Maybe there are other solvents. In particular, ammonia. And we knew before Huygens that there is ammonia on Titan. Now. Look here. Look what the Huygens GCMS found.’ He pointed to a diagram of a molecule shaped like a figure eight on its side, with some of its edges highlighted in blue for double covalent bonds.

‘What is it?’

‘Ammono-guanine. That is, guanine with the water chemistry systematically replaced by ammonia.’ He looked up at her, the multicoloured diagram reflected in his glasses. ‘Do you get it? Exactly what we’d have expected to have found, if some ammonia-based analogue of terrestrial life processes was going on down there. Look at these ratios.’ He pulled up another image. ‘See that? Here, close to the surface, you have a depletion of methane and gaseous nitrogen, and a surplus of ammonia and cyanogen, compared to the atmosphere’s average. The analogy is clear. Methane and nitrogen are being used in place of monose sugars and oxygen, and you have ammonia and cyanogen instead of water and carbon dioxide –’

‘What are you saying, Rosenberg?’

‘Respiration,’ he said. ‘Don’t you get it? Something down there has been breathing nitrogen, and exhaling ammonia.’

‘So, could it mean life?’

He looked puzzled by the question. ‘Yes. That’s the point. Of course it could.’

She frowned, staring at the molecular imagery. It was exciting, yes, but it was hardly the electric thrill she’d been hoping for. Even those blurred images of the microfossils in that meteorite from Mars had had more sex appeal than this obscure stuff.

‘What do you think we should do about this?’

‘Send another probe, of course,’ he said, staring into the screen. ‘It ought to be a sample-return. We’ve just got to follow this up. Look at this.’

He studied his results, and Jackie studied him.

Right now, her own mother was on orbit, in Columbia.

In the long months of her mother’s work absences, Jackie had often wondered why it was always people with no life of their own on this planet – Rosenberg, her own mother after her lawyer husband walked out with his secretary – who became obsessive about finding life on others.

Anyhow it was academic. The funding just wasn’t there. Maybe not for the rest of your working life, Rosenberg, she thought sadly. This data, here, might be all you’ll ever see.

Rosenberg flexed his fingers, as if itching to thrust them into the ammonia-soaked slush of Titan.

‘Lei Feng Number One, there are five minutes to go. Please close the mask of your helmet.’

Jiang obeyed, locking the heavy visor in place with a click of aluminum. ‘My helmet is shut. I am in the preparation regime.’

‘Four minutes and thirty seconds to go.’

As her helmet enclosed her she was aware of a change in the ambient sound; she was shut in with the sound of her own voice, the soft words of the launch controllers in the firing room, the hiss of oxygen and the scratch of her own breathing.

Impatience overwhelmed her. Let the count proceed, let her fly to orbit, or die in the attempt!

Still the holds kept off: still she waited for the final, devastating malfunction which might abort the flight completely.

But the holds did not come; the counting continued.

The voices of the firing room controllers fell silent. There was a moment of stillness.

Jiang lay in the warm, ticking comfort of her xiaohao, the little Mao bell motionless above her, the couch a comfortable pressure beneath her, no sound but the soft hiss of static in the speakers pressed against her ear.

She closed her eyes.

And so the countdown reached its climax, as it had for Gagarin, Glenn and Armstrong before her.

BOOK ONE Landing

As the pilots prepared for the landing, Columbia’s flight deck took on the air of a little cave, Benacerraf thought, a cave glowing with the light of the crew’s fluorescent glareshields, and of Earth. Despite promises of upgrades, this wasn’t like a modern airliner, with its ‘glass’ cockpit of computer displays. The battleship-grey walls were encrusted with switches and instruments that shone white and yellow with internal light, though the surfaces in which they were embedded were battered and scuffed with age. There was even an eight-ball attitude indicator, right in front of Tom Lamb, like something out of World War Two; and he had controls the Wright brothers would have recognized: pedals at his feet, a joystick between his legs.

There was a constant, high-pitched whir, of environment control pumps and fans.

Lamb, sitting in Columbia’s left-hand commander’s seat, punched the deorbit coast mode program into the keyboard to his right. Benacerraf, sitting behind the pilots in the Flight Engineer’s jump seat, followed his keystrokes. OPS 301 PRO. Right. Now he began to check the burn target parameters.

Bill Angel, Columbia’s pilot, was sitting on the right hand side of the flight deck. ‘I hate snapping switches,’ he said. ‘Here we are in a new millennium and we still have to snap switches.’ He grinned, a little tightly. It was his first flight, and now he was coming up to his first landing. And, she thought, it showed.

Lamb smiled, without turning his head. ‘Give me a break,’ he said evenly. ‘I’m still trying to get used to fly by wire.’

‘Still missing that old prop wash, huh, Tom?’

‘You got it.’

Amid the bull, the two of them began to prepare the OMS orbital manoeuvring engines for their deorbit thrusting. Lamb and Angel worked through their checklist competently and calmly: Lamb with his dark, almost Italian looks, flecked now with grey, and Angel the classic WASP military type, with a round, blond head, shaven at the neck, eyes as blue as windows.

Benacerraf was kitted out for the landing, in her altitude protection suit with its oxygen equipment, parachutes, life-raft and survival equipment. She was strapped to her seat, a frame of metal and canvas. Her helmet visor was closed.

She had felt safe on orbit, cocooned by the Shuttle’s humming systems and whirring fans. Even the energies of launch had become a remote memory. But now it was time to come home. Now, rocket engines had to burn to knock Columbia out of orbit, and then the orbiter would become a simple glider, shedding its huge orbital energy in a fall through the atmosphere thousands of miles long, relying on its power units to work its aerosurfaces.

They would get one try only. Columbia had no fuel for a second attempt.

Benacerraf folded her hands in her lap and watched the pilots, following her own copy of the checklist, boredom competing with apprehension. It was, she thought, like going over the lip of the world’s biggest roller-coaster.

On the morning of Columbia’s landing at Edwards, Jake Hadamard flew into LAX.

An Agency limousine was waiting for him, and he was driven out through the rectangular-grid suburbs of LA, across the San Gabriel Mountains, and into the Mojave. His driver – a college kid from UCLA earning her way through an aeronautics degree – seemed excited to have NASA’s Administrator in the back of her car, and she wanted to talk, find out how he felt about the landing today, the latest Station delays, the future of humans in space.

Hadamard was able to shut her down within a few minutes, and get on with the paperwork in his briefcase.

He was fifty-two. And he knew that with his brushed-back silver-blond hair, his high forehead and his cold blue eyes – augmented by the steel-rimmed spectacles he favoured – he could look chilling, a whiplash-thin power from the inner circles of government. Which was how he thought of himself.

The paperwork – contained in a softscreen which he unfolded over his knees – was all about next year’s budget submission for the Agency. What else? Hadamard had been Administrator for three years now, and every one of those years, almost all his energy had been devoted to preparing the budget submission: trying to coax some kind of reasonable data and projections out of the temperamental assholes who ran NASA’s centers, then forcing it through the White House, and through its submission to Congress, and all the complex negotiations that followed, before the final cuts were agreed.

And that was always the nature of it, of course: cuts.

Hadamard understood that.

Jake Hadamard, NASA Administrator, wasn’t any kind of engineer, or aerospace nut. He’d risen to the board of a multinational supplier of commodity staples – basic foodstuffs, bathroom paper, soap and shampoo. High volume, low differentiation; you made your profit by driving down costs, and keeping your prices the lowest in the marketplace. Hadamard had achieved just that by a process of ruthless vertical integration and horizontal acquisition. He hadn’t made himself popular with the unions and the welfare groups. But he sure was popular with the shareholders.

After that he’d taken on Microsoft, after that company had fallen on hard times, and Bill Gates was finally deposed and sent off to dream his Disneyland dreams. By cost-cutting, rationalization and excising a lot of Gates’s dumber, more expensive fantasies – and by ruthlessly using Microsoft’s widespread presence to exclude the competition, so smartly and subtly that the anti-trust suits never had a chance to keep up – Hadamard had taken Microsoft back to massive profit within a couple of years.

With a profile like that, Hadamard was a natural for NASA Administrator, in these opening years of the third millennium.

And even in his first month he’d won a lot of praise from the White House for the way he’d beat up on the United Space Alliance, the Boeing-Lockheed consortium that ran Shuttle launches, and then on Loral, the company which had bought out IBM’s space software support division.

Hadamard planned to do this job for a couple more years, then move up to something more senior, probably within the White House. The long-term plan for NASA, of course, was to subsume it within the Department of Agriculture, but Hadamard didn’t intend to be around that long. Let somebody else take whatever political fall-out there was from that final dismantling, when all the wrinkly old Moonwalker guys like Tom Lamb and Marcus White got on the TV again, with their premature osteoporosis and their heart problems, and started bleating about the heroic days.

Hadamard was under no illusion about his own position. He wasn’t here to deliver some kind of terrific new Apollo program. He was here to administer a declining budget, as gracefully as he could, not to bring home Moonrocks.

There had been no big new spacecraft project since the Cassini thing to Saturn that was launched in 1997, and even half of that was paid for by the Europeans. There sure as hell wasn’t going to be any new generation of Space Shuttle – not in his time, not as long as a couple of decades’ more mileage could be wrung out of the four beat-up old birds they had flying up there. The aerospace companies – Boeing North American, Lockheed Martin – did a lot of crying about the lack of seedcorn money from NASA, the stretching-out of the X-33 Shuttle replacement program. But if the companies were so dumb, so politically naive, as not to be able to see that NASA wasn’t actually supposed to make access to space easy and routine, then the hell with them.

The car turned onto Rosamond Boulevard, passed a checkpoint, and then arrived at the main gate of Edwards Air Force Base. The driver showed her pass, and the limo was waved through.

He folded up his softscreen and put it in his breast pocket.

They arrived at the center of the base, the Dryden Flight Research Center. The parking lot was maybe half full, and there was a mass of network trucks and relay equipment outside the cafeteria.

He shivered when he got out of the car; the November sun still hadn’t driven off the chill of the desert night. The dry lake beds stretched off into the distance, and he could see sage brush and Joshua trees peppered over the dirt, diminishing to the eroded mountains at the horizon. Hadamard looked for his reception.

Barbara Fahy settled into her position in the FCR – pronounced ‘Ficker’, for Flight Control Room. She was the lead Flight Director with overall responsibility for STS-143, and the Flight Director of the team of controllers for the upcoming entry phase.

Right now, Columbia was still half a planet away from the Edwards Air Force Base landing site at California; the primary landing site, at Kennedy, had waved off because of a storm there. Now Fahy checked weather conditions at Edwards. The data came in from a meteorology group here at JSC. Cloud cover under ten thou was less than five per cent. Visibility was eight miles. Crosswinds were under ten knots. There were no thunderstorms or rain showers for forty miles. It was all well within the mission rules for landing.

Everything, right now, looked nominal.

She glanced around the FCR. There was an air of quiet expectancy as her crew took over their stations and settled in, preparing for this mission’s final, crucial – and dangerous – phase.

This FCR was the newest of the three control rooms here in JSC’s Building 30; the oldest, on the third floor, dated back to the days of Gemini and Apollo, and had been flash-frozen as a monument to those brave old days. Fahy still preferred the older rooms, with their blocky rows of benches, the workstations with bolted-in terminals and crude CRTs and keyboards, all hard-wired, so limited the controllers would bring in fold-up softscreens to do the heavy number-crunching. Damn it, she’d liked the old Gemini mission patches on the walls, and the framed retirement plaques, and the big old US flag at front right, beside the plot screens; she even liked the ceiling tiles and the dingy yellow gloom, and the comforting litter of yellow stickies and styrofoam coffee cups and the ring binders full of mission rules …

But this room was more modern. The controllers’ DEC Alpha workstations were huge, black and sleek, with UNIX-controlled touch screens. The display/control system, the big projection screens at the front of the FCR, showed a mix of plots, timing data and images of an empty runway at Edwards. The decor was already dated – very nineties, done out in blue and grey, with a row of absurd pot-plants at the back of the room, which everyone ritually tried to poison with coffee dregs and soda. It was soulless. Nothing heroic had happened here. Of course, Fahy hoped nothing would, today.

Fahy began to monitor the flow of operations, through her console and the quiet voices of her controllers on their loops: Helium isolation switches closed, all four. Tank isolation switches open, all eight. Crossfeed switches closed. Checking aft RCS. Helium press switches open …

Fahy went around the horn, checking readiness for the deorbit burn.

‘Got the comms locked in there, Inco?’

‘Nice strong signal, Flight.’

‘How about you, Fido?’

‘Coming down the center of the runway, Flight, no problem.’

‘Guidance, you happy?’

‘Go, Flight.’

‘DPS?’

‘All four general purpose computers and the backup are up, Flight; all four GPCs loaded with OPS 3 and linked as redundant set. OMS data checked out.’

‘Surgeon?’

‘Everyone’s healthy, Flight.’

‘Prop?’

‘OMS and RCS consumables nominal, Flight.’

‘GNC?’

‘Guidance and control systems all nominal.’

‘MMACS?’

‘Thrust vector control gimbals are go. Vent door closed.’

‘EGIL?’

‘EGIL’ was responsible for electrical systems, including the fuel cells. ‘Rog, Flight. Single APU start …’

And so it went. Mission Control was jargon-ridden, seemingly complex and full of acronyms, but the processes at its heart were simple enough. The three key functions were TT&C: telemetry, tracking and command. Telemetry flowed down from the spacecraft into Fahy’s control center, for analysis, decision-making and control, and commands and ranging information were uploaded back to the craft.

It was simple. Fahy knew her job thoroughly, and was in control. She felt a thrill of adrenaline pumping through her veins, and she laid her hands on the cool surface of her workstation.

She’d come a long way to get to this position.

She’d started as a USAF officer, working as a launch crew commander on a Minuteman ICBM, and as a launch director for operational test launches out on the Air Force’s western test range. She’d come here to JSC to work on a couple of DoD Shuttle missions. After that she had resigned from the USAF to continue with NASA as a Flight Director.

As a kid, she’d longed to be an astronaut: more than that, a pilot, of a Shuttle. But as soon as she spent some time in Mission Control she realized that Shuttle was a ground show. Shuttle could fly itself to orbit and back to a smooth landing without any humans aboard at all. But it wouldn’t get off the ground without its Mission Controllers. This was the true bridge of what was still the world’s most advanced spacecraft.

She’d been involved with this mission, STS-143, for more than a year now, all the way back to the cargo integration review. In the endless integrated sims she’d pulled the crew and her team – called Black Gold Flight, after the Dallas oil-fields close to her home – into a tight unit.

And she’d been down to KSC several times before the launch, just so she could sit in OV-102 – Columbia – and crawl around every inch of space she could get to. As far as she was concerned the orbiter was her machine, five million pounds of living, breathing aluminum, kapton and wires. She liked to know the orbiter as well as she knew the mission commander, and every one of the four orbiters had its own personality, like custom cars.

Columbia, especially, was like a dear old friend, the first spacegoing orbiter to be built, a spacecraft which had travelled as far as from Earth to the sun.

And now Barbara Fahy was going to bring Columbia home.

‘Capcom, tell the crew we have a go for deorbit burn.’

Lamb acknowledged the capcom. ‘Rog. Go for deorbit.’

The capcom said, ‘We want to report Columbia is in super shape. Almost no write-ups. We want her back in the hangar.’

‘Okay, Joe. We know it. This old lady’s flying like a champ.’

‘We’re watching,’ the capcom, Joe Shaw, said. ‘Tom, you can start to manoeuvre to burn attitude whenever convenient.’

‘You got it.’

Lamb and Angel started throwing switches in a tight choreography, working their way down their spiral-bound checklists. Benacerraf shadowed them. She watched the backs of their heads as they worked. The two military-shaved necks moved in synchronization, like components of some greater machine.