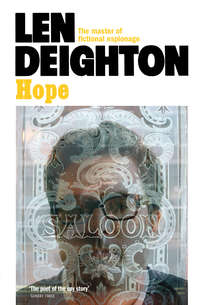

Hope

‘Look, George,’ I said in one final attempt to make him see sense. ‘To you it’s obvious that you’re not an enemy agent – just a well-meaning philanthropist – but don’t rely upon others being so perceptive. The sort of people I work for think that there is no smoke without fire. Cool it. Or you are likely to find a fire-extinguisher up your arse.’

‘I live in Switzerland,’ said George.

‘So a Swiss fire-extinguisher.’

‘I told you I’m sorry, Bernard. You know I wouldn’t have had this happen for the world. I can’t blame you for being angry. In your place I would be angry too.’ Both his arms were clasped round the cheap briefcase as if it was a baby. I suddenly guessed that it was stuffed with money; money that had come from the exchange of the gold.

At that I gave up. There are some people who won’t learn by good advice, only by experience. George Kosinski was that sort of person.

Soon after that a man I recognized as George’s driver and handyman arrived. He brought a car rug to wrap around the injured man and lifted him with effortless ease. George watched as if it was his own sick child. Perhaps it was pain that caused the injured man’s eyes to flicker. His lips moved but he didn’t speak. Then he was carried down to the car.

‘I’m sorry, Bernard,’ said George, standing at the door as if trying to be contrite. ‘If you have to report it, you have to. I understand. You can’t risk your job.’

I cleaned the mat as well as possible, got rid of the worst marks in the bathroom and soaked a bloody towel in cold water before sending it to the laundry. In my usual infantile fashion, I decided to wait and see if Fiona noticed any of the marks. As a way of making an important decision it was about as good as spinning a coin in the air, but Fiona had eyes for little beyond the mountains of work she brought home every evening, so I didn’t mention my uninvited visitors to anyone. But my hopes that George and his antics were finished and forgotten did not last beyond the following week, when I returned from a meeting and found a message on my desk summoning me to the presence of my boss Dicky Cruyer, newly appointed European Controller.

I opened the office door. Dicky was standing behind his desk, twisting a white starched handkerchief tight around his wounded fingers, while half a dozen tiny drips of blood patterned the report he had brought back from his meeting.

There was no need for him to explain. I’d been on the top floor and heard the sudden snarling and baritone growls. The only beast permitted through the guarded front entrance of London Central was the Director-General’s venerable black Labrador, and it only came when accompanied by its master.

‘Berne,’ said Dicky, indicating the papers freshly arrived in his tray. ‘The Berne office again.’

I put on a blank expression. ‘Berne?’ I said. ‘Berne, Switzerland?’

‘Don’t act the bloody innocent, Bernard. Your brother-in-law lives in Switzerland, doesn’t he?’ Dicky was trembling. His sanguinary encounter with the Director-General and his canine companion had left him wounded in both body and spirit. It made me wonder what condition the other two were in.

‘I’ve never denied it,’ I said.

The door to the adjoining office opened. Jennifer, the youngest, most devoted and attentive of Dicky’s female assistants, put her head round the door and said: ‘Shall I get antiseptic from the first-aid box, Mr Cruyer?’

‘No,’ said Dicky in a stagy whisper over his shoulder, vexed that word of his misfortune had spread so quickly. ‘Well?’ he said, turning to me again.

I shrugged. ‘We all have to live somewhere.’

‘Four Stasi agents pass through in seven days? Are you telling me that’s just a coincidence?’ A pensive pause. ‘They went to see your brother-in-law in Zurich.’

‘How do you know where they went?’

‘They all went to Zurich. It’s obvious, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t know what you’re implying,’ I said. ‘If the Stasi want to talk to George Kosinski they don’t have to send four men to Zurich; roughnecks that even our pen-pushers in Berne can recognize. I mean, it’s a bit high-profile, isn’t it?’

Dicky looked round to see if Jennifer was still standing in the doorway looking worried. She was. ‘Very well, then,’ he said, sitting down suddenly as if surrendering to his pain. ‘Get the antiseptic.’ The door closed and, as he tightened the handkerchief round his fingers, he noticed the bloodstains on his papers.

‘You should have an anti-tetanus shot,’ I advised. ‘That dog is full of fleas and mange.’

Dicky said: ‘Never mind the dog. Let’s keep to the business in hand. Your brother-in-law is in contact with East German intelligence, and I’m going over there to face him with it.’

‘When?’

‘This weekend. And you are coming with me.’

‘I have to finish all that material you gave me yesterday. You said the D-G wanted the report on his desk on Monday.’

Dicky eyed me suspiciously. We both knew that he recklessly used the name of the Director-General when he wanted work done hurriedly or late at night. ‘He’s changed his mind about the report. He told me to take you to Switzerland with me.’

Now it was possible to see a little deeper into Dicky’s state of mind. The questions he had just put to me were questions he’d failed to answer to the D-G’s satisfaction. The Director had then told Dicky to take me along with him, and it was that that had dented Dicky’s ego. The nip from the dog was extracurricular. ‘Because it’s your brother-in-law,’ he added, lest I began to think myself indispensable.

Using his uninjured hand Dicky picked up his phone and called Fiona, who worked in the next office. ‘Fiona, darling,’ he said in his jokey drawl. ‘Hubby is with me. Could you join us for a moment?’

I went and looked out of the window and tried to forget I had a crackpot brother-in-law in whom Dicky was taking a sudden and unsympathetic interest. Summer had passed; we had winter to endure before it came again but this was a glorious golden day, and from this top-floor room I could see across the London basin to the high ground at Hampstead. The clouds, gauzy and grey like a bundle of discarded bandages, were fixed to the ground by shiny brass pins pretending to be sunbeams.

My wife came in, her face darkened with the stern expression that I’d learned to recognize as one she wore when wrenched away from something that needed uninterrupted concentration. Fiona’s work load had become the talk of the top floor. And she handled the political decisions with consummate skill. But I saw in her eyes that bright gleam a light bulb provides just before going ping.

‘Yes, Dicky?’ she said.

‘I’m enticing your hubby away for a brief fling in Zurich, Fiona my dearest. We must leave Sunday morning. Can you endure a weekend without him?’

Fiona looked at me sternly. I winked at her but she didn’t react. ‘Must he go?’ she said.

‘Duty calls,’ said Dicky.

‘What did you do to your hand, Dicky?’

As if in response, Jennifer arrived with antiseptic, cotton wool and a packet of Band-Aids. Dicky held his hand out like some potentate accepting a vow of fidelity. Jennifer crouched and began work on his wound.

‘The children were coming home on Sunday,’ Fiona told Dicky. ‘But if Bernard is going to be on a trip, I’ll lock myself away and work on those wretched figures you need for the Minister.’

‘Splendid,’ said Dicky. ‘Ouch, that hurts,’ he told Jennifer.

‘I’m sorry, Mr Cruyer.’

To me Fiona said: ‘Daddy suggests keeping the children with him a little longer.’ Perhaps she saw the quizzical look in my face for, in explanation, she added: ‘I phoned them this morning. It’s their wedding anniversary.’

‘We’ll talk about it,’ I said.

‘I’ve told Daddy to reserve places for them at the school next term, just in case.’ She clasped her hands together as if praying that I would not explode. ‘If we lose the deposit, so be it.’

For a moment I was speechless. Her father was doing everything he could to keep my children with him, and I wanted them home with us.

Dicky, feeling left out of this conversation, said: ‘Has Daphne been in touch, by any chance?’

This question about his wife was addressed to Fiona, who looked at him and said: ‘Not since I called and thanked her for that divine dinner party.’

‘I just wondered,’ said Dicky lamely. With Fiona looking at him and waiting for more, he added: ‘Daph’s been a bit low lately; and there are no friends like old friends. I told her that.’

‘Shall I call her?’

‘No,’ said Dicky hurriedly. ‘She’ll be all right. I think she’s going through the change of life.’

Fiona grinned. ‘You say that every time you have a tiff with her, Dicky.’

‘No, I don’t,’ said Dicky crossly. ‘Daphne needs counselling. She’s making life damned difficult right now. And with all the work piled up here I don’t need any distractions.’

‘No,’ said Fiona, backing down and becoming the loyal assistant. Now that Dicky had manoeuvred himself into being the European Controller, while still holding on to the German Desk, no one in the Department was safe from his whims and fancies.

Dicky said: ‘Work is the best medicine. I’ve always been a workaholic; it’s too late to change now.’

Fiona nodded and I looked out of the window. There was really no way to respond to this amazing claim by the Rip Van Winkle of London Central, and if I’d caught her eye we might both have rolled around on the floor with merriment.

We stayed at home that evening, eating dinner I’d fetched from a Chinese take-away. Fulham was too far to go for shrivelled duck and plastic pancakes but Fiona had read about it in a magazine at the hairdresser’s. That restaurant critic must have led the dullest of lives to have found the black bean spare-ribs ‘memorable’. The bill might have proved even more memorable for him, had restaurant critics been given bills.

‘You don’t like it?’ Fiona said.

‘I’m full.’

‘You’ve eaten hardly anything.’

‘I’m thinking about my trip to Zurich.’

‘It won’t be so bad.’

‘With Dicky?’

‘Dicky depends upon you, he really does,’ she said, her feminine reasoning making her think that this dependence would encourage me to overlook his faults for the sake of the Department.

‘No more rice, no more fish and no more pancakes,’ I said as she pushed the serving plates towards me. ‘And certainly no more spare-ribs.’

Fiona switched on the TV to catch the evening news. There was a discussion between four people best known for their availability to appear on TV discussion programmes. A college professor was holding forth on the latest news from Poland. ‘…Historically the Poles lack a consciousness of their own position in the European dimension. For hundreds of years they have acted out a totemic role that they lack the capacity to sustain. Now I think the Poles are about to get a rude awakening.’ The professor touched his beard reflectively. ‘They have pushed and provoked the Soviet Union… The Warsaw Pact autumn exercises are taking place along the border. Any time now the Russian tanks will roll across it.’

‘Literally?’ asked the TV anchor man.

‘It is time the West acted,’ said a woman with a Polish Solidarity badge pinned to her Chanel suit.

‘Yes, literally,’ said the professor with that determined solemnity with which those past military age discuss war. ‘The Soviets will use it as a way of cautioning the hotheads in the Baltic States. We must make it absolutely clear to Chairman Gorbachev that any action, I do mean any action, he takes against the Poles will not be permitted to provoke a major East–West conflict.’

‘Who will rid me of these troublesome Poles? Is that how the Americans see it?’ the Solidarity woman asked bitterly. ‘Best abandon the Poles to their fate?’

‘When?’ said the TV anchor man. Already the camera was tracking back to show that the programme was ending. A gigantic Polish eagle of polystyrene on a red and white flag formed the backdrop to the studio.

‘When the winter hardens the ground enough for their modern heavy armour to go in,’ answered the professor, who clearly knew that a note of terror heard on the box in the evening was a newspaper headline by morning. ‘They’ll crush the Poles in forty-eight hours. The Russian army has one or two special Spetsnaz brigades that have been trained to suppress unruly satellites. One of them, stationed at Maryinagorko in the Byelorussian Military District, was put on alert two days ago. Yes, Polish blood will flow. But quite frankly, if a few thousand Polish casualties are the price we pay to avoid World War Three, we must thank our lucky stars and pay up.’

Loud stirring music increased in volume to eventually drown his voice and, while the panel sat in silhouette, a roller provided details of about one hundred and fifty people who had worked on this thirty-minute unscripted discussion programme.

The end roller was still going when the phone rang. It was my son Billy calling from my father-in-law’s home where he was staying. ‘Dad? Is that you, Dad? Did Mum tell you about the weekend?’

‘What about the weekend?’ I saw Fiona frowning as she watched me.

‘It’s going to be super. Grandad is taking us to France,’ said Billy, almost bursting with excitement. ‘To France! Just for one night. A private plane to Dinard. Can we go, Dad? Say yes, Dad. Please.’

‘Of course you can, Billy. Is Sally keen to go?’

‘Of course she is,’ said Billy, as if the question was absurd. ‘We are going to stay in a château.’

‘I’ll see you the following weekend then,’ I said as cheerfully as I could manage. ‘And you can tell me all about it.’

‘Grandad’s bought a video camera. He’s going to take pictures of us. You’ll be able to see us. On the TV!’

‘That’s wonderful,’ I said.

‘He’s already taken videos of his best horses. Of course I’d rather be with you, Dad,’ said Billy, desperately trying to mend his fences. Perhaps he heard the disappointment.

‘All the world’s a video,’ I improvised. ‘And all the men and women merely directors. They have their zooms and their pans, and one man in his time plays back the results too many times. Is Sally there?’

‘That’s a good joke,’ said Billy with measured reserve. ‘Sally’s in bed. Grandad is letting me stay up to see the TV news.’ Fiona had quietened our TV, but over the phone from Grandad’s I could hear the orchestrated fanfares and drumrolls that introduce the TV news bulletins; a presentational style that Dr Goebbels created for the Nazis. I visualized Grandad fingering the volume control and urging our conversation to a close.

‘Sleep well, Billy. Give my love to Sally. And to Grandad and Grandma.’ I held up the phone, offering it, but Fiona shook her head. ‘And love from Mummy too,’ I said. Then I hung up.

‘It’s not my doing,’ said Fiona defensively.

‘Who said it was?’

‘I can see it on your face.’

‘Why can’t your father ask me?’

‘It will be lovely for them,’ said Fiona. ‘And anyway you couldn’t have gone on Sunday.’

‘I could have gone on Saturday.’ The silent TV pictures changed rapidly as the news flashed quickly from one calamity to another.

‘It wasn’t my idea,’ she snapped.

‘I don’t see why I should be the focus of your anger,’ I said mildly. ‘I’m the victim.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘You’re always the victim, Bernard. That’s what makes you so hard to live with.’

‘What then?’

She got up and said: ‘Let’s not argue, darling. I love the children just as much as you do. Don’t keep putting me in the middle.’

‘But why didn’t you tell me?’ I said.

‘Daddy is so worried. The stock-market has become unpredictable, he says. He doesn’t know what he’ll be worth next week.’

‘For him that’s new? For me it’s always been like that.’

This aggravated her. ‘With you on one side and my father on the other, sometimes I just want to scream.’

‘Scream away,’ I said.

‘I’m tired. I’ll clean my teeth.’ She rose to her feet and put everything she had into a smile. ‘Tomorrow we’ll have lunch, and fight all you want.’

‘Lovely! And I’ll arm-wrestle the waiter to settle the bill,’ I said. ‘Switch off that bloody TV, will you?’

She switched it off and went to bed leaving the desolation of our meal still on the table. Sitting there staring at the blank screen of the TV I found myself simmering with anger at the way my father-in-law was holding on to my children. But was Fiona fit and well enough to be a proper mother to them? Perhaps Fiona would remain incapable of looking after them. Perhaps she knew that. And perhaps my awful father-in-law knew it. Perhaps I was the only one who couldn’t see the tragic situation for what it really was.

I woke up in the middle of the night. The windows shook and the wind was howling and screaming as I’d never heard it shriek before in England. It was like a nightmare from which there was no escape, and I was an expert in nightmares. From somewhere down below in the street I heard a loud crash of glass and then another and another, resounding like surf upon a rocky shore.

‘My God!’ said Fiona sleepily. ‘What on earth…?’

I switched on the bedside light but there was no electricity. I heard clicking as Fiona tried her light-switch too. The electric bedside clock was dark. I threw back the bedclothes and, stepping carefully in the darkness, went to the window. The street lighting had failed and everything was gloomy. Two police cars were stopped close together behind a fire engine, and a group of men were conferring outside the smashed windows of the bank on the corner. They ducked their heads as a great roar of wind brought the sound of more breaking glass, and debris – newspapers and the lids of rubbish bins – came bowling along the street. I heard the distant sirens of police cars and fire engines going down Park Lane at high speed.

‘Phone the office,’ I told Fiona, handing her the flashlight that I keep in the first-aid box. ‘Use the Night Duty Officer’s direct line. Ask them what the hell’s going on. I’ll try to see what’s happening in the street.’

With the window open I could lean out and look along the street. The garbage bins had been blown over, shop-windows broken, and merchandise of all kinds was distributed everywhere: high-fashion shoes mixed with groceries and rubbish, with fragments of paper and packets being whirled high into the air by the wind. There were tree branches too: thousands of twigs as well as huge boughs of leafy timber that must have flown over the rooftops from the park. Some of them were heaving convulsively in the continuing windstorm, like exhausted birds resting after a long flight. Fragmented glass was dashed across the road, glittering like diamonds in the beams of the policemen’s flashlights.

I could hear Fiona moving around in the kitchen, then the gush of running water and the plop of igniting gas as she boiled a kettle for tea.

When she came back into the room she came to the window, putting a hand on my arm as she peered over my shoulder. She said: ‘The office says there are freak windstorms gusting over 100 miles an hour. It’s a disaster. The whole Continent is affected. The forecasters in France and Holland gave out warnings but our weather people said it wasn’t going to happen. Heavens, look at the broken shop-windows.’

‘This might be your big chance for a new Chanel suit.’

‘Will there be looting?’ she asked, as if I was some all-knowing prophet.

‘Not too much at this time of night. Black up your face and put on your gloves.’

‘It’s not funny, darling. Shall I phone Daddy?’

‘It will only alarm them more. Let’s hope they sleep through it.’

She poured tea for us both and we sat there, with only a glimmer of light from the window, drinking strong Assam tea and listening to the noise of the storm. Fiona was very English. The English met every kind of disaster, from sudden death to threatened invasions, by making tea. Growing up in Berlin I had never acquired the habit. Perhaps that was at the root of our differences. Fiona had a devout faith in England, a legacy of her middle-class upbringing. Its rulers and administration, its history and even its cooking was accepted without question. No matter how much I tried to share such deeply held allegiances I was always an outsider looking in.

‘I’ve got a long day tomorrow, so I’m going right back to bed.’ She lifted her cup and drained the last of her tea. I noticed the cup she was using was from a set I’d bought when I set up house with Gloria. I’d tried to dispose of everything that would bring back memories of those days, but I’d forgotten about the big floral-pattern cups.

Gloria’s name was never mentioned but her presence was permanent and all-pervading. Would Fiona ever forgive me for falling in love with that glamorous child? And would I ever be able to forgive Fiona for deserting me without warning or trust? Our marriage had survived by postponing such questions, but eventually it must be tested by them.

‘Me too,’ I said.

Fiona put her empty cup on the tray and reached for mine. ‘You haven’t touched your tea,’ she said. She knew about the cups of course. Women instinctively know everything about other women.

‘It keeps me awake.’ Not that there was much of the night remaining to us.

‘You’re not easy to live with, Bernard,’ she said, with a formality that revealed that this was something she’d told herself many times.

‘I was thinking about something else,’ I confessed. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘You can’t wait to get away,’ she said, as if taking note of something beyond her control, like the storm outside the window.

‘It’s Dicky’s idea.’

‘I didn’t say it wasn’t.’ She stood up and gathered the sugar and milk jug, and put them on the tray.

‘I’d rather stay with you,’ I said.

She smiled a lonely distant smile. Her sadness almost broke my heart. I was going to stand up and embrace her, but while I was still thinking about it she had picked up the tray and walked away. In such instants are our lives changed; or not changed.

With characteristic gravity the news men made the high winds of October 1987 into a hurricane. But it was a newsworthy event nevertheless. Homes were wrecked and ships sank. Cameras turned. The insured sweated; underwriters faltered; glaziers rejoiced. Hundreds and thousands of trees were ripped out of the English earth. So widespread was the devastation that even the meteorological gurus were moved to admit that they had perhaps erred in their predictions for a calm night.

I contrive, as far as is possible considering our relative ranking in the Department, to make my travel arrangements so that they exclude Dicky Cruyer. Several times during our trip to Mexico City a few years ago, I had vowed to resign rather than share another expedition with him. It was not that he made a boring travelling companion, or that he was incapable, cowardly, taciturn or shy. At this moment, he was practising his boyish charm on the Swiss Air stewardess in a demonstration of social skill far beyond anything that I might accomplish. But Dicky’s intrepid behaviour and reckless assumptions brought dangers of a sort I was not trained to endure. And I was tired of his ongoing joke that he was the brains and I was the brawn of the combination.

It was a Monday morning in October in Switzerland. Birds sang to keep warm, and the leaves were turning to rust on dry and brittle branches. The undeclared reason for my part in this excursion was that I knew the location of George Kosinski’s lakeside hideaway near Zurich. It was a secluded spot, and George had an obsession about keeping his name out of phone books and directories.

It was a severely modern house. Designed with obvious deference to the work of Corbusier, it exploited a dozen different woods to emphasize a panelled mahogany front door and carved surround. There was no reply to repeated ringing, and Dicky said flippantly: ‘Well, let’s see how you knock down the door, Bernard… Or do you pick the lock with your hairpin?’