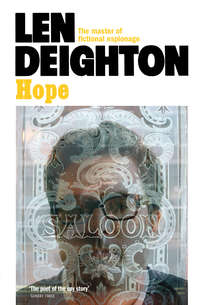

Hope

Across the road a man in coveralls was painstakingly removing election posters from a wall. The national elections had taken place the previous day but already the Swiss were clearing away the untidy-looking posters. I smiled at Dicky. I wasn’t going to smash down a door in full view of a local municipal employee, and certainly not the sort of local municipal employee found in law-abiding Switzerland. ‘George might be having an afternoon nap,’ I said. ‘He’s retired; he takes life slowly these days. Give him another minute.’ I pressed the bell push again.

‘Yes,’ said Dicky knowingly. ‘There are few worse beginnings to an interview than smashing down someone’s front door.’

‘That’s it, Dicky,’ I said in my usual obsequious way, although I knew many worse beginnings to interviews, and I had the scars and stiff joints to prove it. But this wasn’t the time to burden Dicky with the adversities of being a field agent.

‘Our powwow might be more private if we all take a short voyage around the lake in his power boat,’ said Dicky.

I nodded. I’d noted that Dicky was nautically attired with a navy pea-jacket and a soft-topped yachtsman’s cap. I wondered what other aspects of George’s lifestyle had come to his attention.

‘And before we start, Bernard,’ he said, putting a hand on my arm, ‘leave the questioning to me. We’ve not come here for a cosy family gathering, and the sooner he knows that the better.’ Dicky stood with both hands thrust deep into the slash pockets of his pea-jacket and his feet well apart, the way sailors do in rough seas.

‘Whatever you say, Dicky,’ I told him, but I felt sure that if Dicky went roaring in with bayonets fixed and sirens screaming, George would display a terrible anger. His Polish parents had provided him with that prickly pride that is a national characteristic and I knew from personal experience how obstinate he could be. George had started as a dealer in unreliable motor cars and derelict property. Having contended with the ferocious dissatisfied customers found in run-down neighbourhoods of London, he was unlikely to yield to Dicky’s refined style of Whitehall bullying.

Again I pressed the bell push.

‘I can hear it ringing,’ said Dicky. There was a brass horseshoe door-knocker. Dicky gave it a quick rat-a-tat.

When there was still no response I strolled around the back of the house, its shiny tiles and heavy glass well suited to the unpredictable winds and weather that came from the lake. From the house well-kept grounds stretched down to the lakeside and the pier where George’s powerful cabin cruiser was tied up. Summer had ended, but today the sun was bright as it darted in and out of granite-coloured clouds that stooped earthward and became the Alps. The air was whirling with dead leaves that settled on the grass to make a scaly bronze carpet. There was a young woman standing on the lawn, ankle-deep in dead leaves. She was hanging out clothes to dry in the cold blustery wind off the lake.

‘Ursi!’ I called. I recognized her as my brother-in-law’s housekeeper. Her hair was straw-coloured and drawn back into a tight bun; her face, reddened by the wind, was that of a child. Standing there, arms upstretched with the laundry, she looked like the sort of fresh peasant girl you see only in pre-Raphaelite paintings and light opera. She looked at me solemnly for a moment before smiling and saying: ‘Mr Samson. How good to see you.’ She was dressed in a plain dark blue bib-front dress, with white blouse and floppy collar. Her frumpy low-heel shoes completed the sort of ensemble in which Switzerland’s wealthy immigrants dress their domestic servants.

‘I’m looking for Mr Kosinski,’ I said. ‘Is he at home?’

‘Do you know, I have no idea where he has gone,’ she said in her beguiling accent. Her English was uncertain and she picked her words with a slow deliberate pace that deprived them of accent and emotion.

‘When did he leave?’

‘Again, I cannot tell you for sure. The morning of the day before yesterday – Saturday – I drove the car for him; to take him on visits in town.’ Self-consciously she tucked an errant strand of hair back into place.

‘You drove the car?’ I said. ‘The Rolls?’ I had seen Ursi drive a car. She was either very short-sighted or reckless or both.

‘The Rolls-Royce. Yes. Twice I was stopped by the police; they could not believe I was allowed to drive it.’

‘I see,’ I said, although I didn’t see any too clearly. George had always been very strict about allowing people to drive his precious Rolls-Royce.

‘In downtown Zurich, Mr Kosinski asks me to drive him round. It is very difficult to park the cars.’

‘Yes,’ I said. I hadn’t realized how difficult.

‘Finally I left him at the airport. He was meeting friends there. Mr Kosinski told me to take… to bring…’ She gave a quick breathless smile. ‘…the car back here, lock it in the garage, and then go home.’

‘The airport?’ said Dicky. He whisked off his sun-glasses to see Ursi better.

‘Yes, the airport,’ she said, looking at Dicky as if noticing him for the first time. ‘He said he was meeting friends and taking them to lunch. He would be drinking wine and didn’t want to drive.’

‘What errands?’ I said.

‘What time did you arrive at the airport?’ Dicky asked her.

‘This is Mr Cruyer,’ I said. ‘I work for him.’

She looked at Dicky and then back at me. Without changing her blank expression she said: ‘Then I arrived here at the house this morning at my usual hour; eight-thirty.’

‘Yes, yes, yes. And bingo – he was gone,’ added Dicky.

‘And bingo – he was gone,’ she repeated in that way that students of foreign languages pounce upon such phrases and make them their own. ‘And he was gone. Yes. His bed not slept upon.’

‘Did he say when he was coming back?’ I asked her.

A look of disquiet crossed her face: ‘Do you think he goes back to his wife?’

Do I think he goes back to his wife! Wait a minute! My respect for George Kosinski’s ability to keep a secret went sky-high at that moment. George was in mourning for his wife. George had come here, to live full-time in this luxurious holiday home of his, only because his wife had been murdered in a shoot-out in East Germany. And his pretty housekeeper doesn’t know that?

I looked at her. On my previous visit here the nasty suspicions to which every investigative agent is heir had persuaded me that the relationship between George and his attractive young ‘housekeeper’ had gone a steamy step or two beyond pressing his pants before he took them off. Now I was no longer so sure. This girl was either too artless, or a wonderful actress. And surely any close relationship between them would have been built upon George being a sorrowing widower?

While I was letting the girl have a moment to rethink the situation, Dicky stepped in, believing perhaps that I was at a loss for words. ‘I’d better tell you,’ he said, in a voice airline captains assume when confiding to their passengers that the last remaining engine has fallen off, ‘that this is an official inquiry. Withholding information could result in serious consequences for you.’

‘What has happened?’ said the girl. ‘Mr Kosinski? Has he been injured?’

‘Where did you take him downtown on Saturday?’ said Dicky harshly.

‘Only to the bank – for money; to the jeweller – they cleaned and repaired his wrist-watch; to church – to say a prayer. And then to the airport to meet his friends,’ she ended defiantly.

‘It’s all right, Ursi,’ I said pleasantly, as if we were playing bad cop, good cop. ‘Mr Kosinski was supposed to meet us here,’ I improvised. ‘So of course we are a little surprised to hear he’s gone away.’

‘I want to know everyone who’s visited him here during the last four weeks,’ said Dicky. ‘A complete list. Understand?’

The girl looked at me and said: ‘No one visits him. Only you. He is so lonely. I told my mother and we pray for him.’ She confessed this softly, as if such prayers would humiliate George if he ever learned of them.

‘We haven’t got time for all this claptrap,’ Dicky told her. ‘I’m getting cold out here. I’ll take a quick look round inside the house, and I want you to tell me the exact time you left him at the airport.’

‘Twelve noon,’ she said promptly. ‘I remember it. I looked at the clock there to know the time. I arranged to visit my neighbour for her to fix my hair in the afternoon. Three o’clock. I didn’t want to be late.’

While Dicky was writing about this in his notebook, she started to pick up the big plastic basket, still half-filled with damp laundry that she had not put on the line. I took it from her: ‘Maybe you could leave the laundry for a moment and make us some coffee, Ursi,’ I said. ‘Have you got that big espresso machine working?’

‘Yes, Mr Samson.’ She gave a big smile.

‘I’ll look round the house and find a recent photo of him. And I’ll take the car,’ Dicky told me. ‘I haven’t got time to sit round guzzling coffee. I’m going to grill all those airport security people. Someone must have seen him go through the security checks. I need the car; you get a taxi. I’ll see you back at the hotel for dinner. Or I’ll leave a message.’

‘Whatever you say, master.’

Dicky smiled dutifully and marched off across the lawn and disappeared inside the house through the back door Ursi had used.

I was glad to get rid of Dicky, if only for the afternoon. Being away from home seemed to generate in him a restless disquiet, and his displays of nervous energy sometimes brought me close to screaming. Also his departure gave me a chance to talk to the girl in Schweitzerdeutsch. I spoke it only marginally better than she spoke English, but she was more responsive in her own language.

‘There’s a beauty shop in town that Mrs Kosinski used to say did the best facials in the whole world,’ I told her. ‘You help me look round the house and we’ll still have time for me to take you there, fix an appointment for you, and pay for it. I’ll charge it to Mr Cruyer.’

She looked at me, smiled artfully, and said: ‘Thank you, Mr Samson.’

After looking out of the window to be quite certain Dicky had departed, I went through the house methodically. She showed me into the master bedroom. There was a photograph of Tessa in a silver frame at his bedside and another photo of her on the chest of drawers. I went into an adjacent room which seemed to have started as a dressing-room but which now had become an office and den. It revealed a secret side of George. Here, in a glass case, there was an exquisite model of a Spanish galleon in full sail. A brightly coloured lithograph of the Virgin Mary stared down from the wall.

‘What are those hooks on the wall for?’ I asked Ursi while I continued my search: riffling through the closets to discover packets of socks, shirts and underclothes still in their original wrappings, and a drawer in which a dozen valuable watches and some gold pens and pencils were carelessly scattered among the silk handkerchiefs.

‘He has taken the rosary with him,’ she said, looking at the hooks on the wall. ‘It was his mother’s. He always took it to church.’

‘Yes,’ I said. I noticed that he’d left Nice Guys Finish Dead beside his bed with a marker in the last chapter. It looked like he planned to return. On the large dressing-room table there were half a dozen leather-bound photograph albums. I flipped through them to see various pictures of George and Tessa. I’d not before realized that George was an obsessional, if often inexpert, photographer who’d kept a record of their travels and all sorts of events, such as Tessa blowing out the candles on her birthday cake, and countless flashlight pictures of their party guests. Many of the photos had been captioned in George’s neat handwriting, and there were empty spaces on some pages showing where photos had been removed.

I opened the door of a big closet beside his cedar-lined wardrobe, and half a dozen expensive items of luggage tumbled out. ‘These cases. Do they all belong to Mr Kosinski?’

‘No. His cases are not there,’ she said, determined to practise her English. ‘But he took no baggage with him to the airport. I know this for sure. I always pack for him when he goes tripping.’

‘These are not his?’ I looked at the collection of expensive baggage. Many of the bags were matching ones embroidered with flower patterns, but there was nothing there to fit with George’s taste.

‘No. I think those all belong to Mrs Kosinski. Mr Kosinski always uses big metal cases and a brown leather shoulder-bag.’

‘Have you ever met Mrs Kosinski?’ I held up a photo of Tessa just in case George had brought some woman here and pretended she was his wife.

‘I have only worked here eight weeks. No, I have not met her.’ She watched me as I looked at the large framed photo hanging over George’s dressing-table. It was a formal group taken at his wedding. ‘Is that you?’ She pointed a finger. It was no use denying that the tall man with glasses looming over the bridegroom’s shoulder, and looking absurd in his rented morning suit and top-hat, was me. ‘And that is your wife?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘She is beautiful,’ said Ursi in an awed voice.

‘Yes,’ I said. Fiona was at her most lovely that day when her sister was married in the little country church and the sun shone and even my father-in-law was on his best behaviour. It seemed a long time ago. In the frame with the colour photo, a horseshoe decoration from the wedding cake had been preserved, and so had a carefully arranged handful of confetti.

George was a Roman Catholic. No matter that Tessa was the most unfaithful of wives, he would never divorce or marry again. He had told me that more than once. ‘For better or worse,’ he’d repeated a dozen times since, and I was never quite sure whether it was to confirm his own vows or remind me of mine. But George was a man of contradictions: of impoverished parents but from a noble family, honest by nature but Jesuitical in method. He drove around a lake in a motor boat while dreaming of Spanish galleons, he prayed to God but supplicated to Mammon; carried his rosary to church, while adorning his house with lucky horseshoes. George was a man ready to risk everything on the movements of the market, but hanging inside his wardrobe there were as many belts as there were braces.

Downstairs again, sitting with Ursi on the imitation zebra-skin sofas in George’s drawing-room, with bands of sunlight across the floor, I was reminded of my previous visit. This large room had modern furniture and rugs that suited the architecture. Its huge glass window today gave a view of the grey water of the lake and of George’s boat swaying with the wake of a passing ferry.

The room reminded me that, despite my protestations to Dicky, George had been in a highly excited state when I was last in this room with him. He’d threatened all kinds of revenge upon the unknown people who might have killed his wife, and even admitted to engaging someone to go into communist East Germany to ferret out the truth about that night when Tessa was shot.

‘We’ll take a taxi,’ I promised Ursi. ‘And we’ll visit every place you went on the afternoon you took him to the airport. Perhaps when we’re driving you’ll remember something else, something that might help us find him.’

‘He’s in danger, isn’t he?’

‘It’s too early to say. Tell me about the bank. Did he get foreign currency? German marks? French francs?’

‘No. I heard him phoning the bank. He asked them to prepare one thousand dollars in twenty-dollar bills – American money.’

‘Traveller’s cheques?’

‘Cash.’

‘Mr Kosinski is my brother-in-law; you know that?’

‘He hasn’t gone back to his wife then?’ she said. She obviously thought that George’s wife was my sister. Perhaps it was better to leave it that way. It was a natural mistake; no one could have mistaken me for George Kosinski’s kin. I was tall, overweight and untidy. George was a small, neat, grey-haired man who had grown used to enjoying the best of everything, except perhaps of wives, for Tessa had found her marriage vows intolerable.

‘He’s in mourning for his wife,’ I said.

She crossed herself. ‘I did not know.’

‘She was killed in Germany. When I was last here he talked about finding his wife’s killer. That could be very dangerous for him.’

She looked at me and nodded like a child being warned about speaking to strangers.

‘What did you think this morning, Ursi?’ I asked her. ‘What did you think when you arrived and found he had gone?’

‘I was worried.’

‘You weren’t so worried that you called the police,’ I pointed out. ‘You went on working; doing the laundry as if nothing was amiss.’

‘Yes,’ she said, and looked over her shoulder as if she thought Dicky might be about to climb through the window and pounce on her. Then she smiled, and in an entirely new and relaxed voice said: ‘I think perhaps he has gone skiing.’

‘Skiing? In October?’

‘On the glacier.’ She was anxious to persuade me. ‘Last week he spent a lot of money on winter sport clothes. He bought silk underwear, silk socks, some cashmere roll-necks and a dark brown fur-lined ski jacket.’

I said: ‘I need to use the phone for long distance.’ She nodded. I called London and told them to dig out George’s passport application and leave a full account of its entries on the hotel fax.

‘Let’s get a cab and go to town, Ursi,’ I said.

We went to the jeweller’s first. Not even Forest Lawn can equal the atmosphere of silent foreboding that you find in those grand jewellery shops on Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse. The glass show-cases were ablaze with diamonds and pearls. Necklaces and brooches; chokers and tiaras; gold wrist-watches and rings glittered under carefully placed spotlights. The manager wore a dark suit and stiff collar, gold cuff-links and a diamond stud in his sober striped tie. His face was politely blank as I walked with Ursi to the counter upon which three black velvet pads were arranged at precisely equal intervals.

‘Yes, sir?’ said the manager in English. He had categorized us already; middle-aged foreigner accompanied by young girl. What could they be here for, except to exchange those vows of carnal sin at which only a jeweller can officiate?

‘Mr George Kosinski is a customer of yours?’

‘I cannot say, sir.’

‘This is Miss Maurer. She works for Mr Kosinski. I am Mr Kosinski’s brother-in-law.’

‘Indeed.’

‘He came to your shop the day before yesterday. He disappeared immediately afterwards. I mean he didn’t come home. We don’t want to go to the police – not yet, at any rate – but we are concerned about him.’

‘Of course, sir,’ he said sympathetically and adjusted the velvet pad on the counter, pulling it a fraction of an inch towards him as if lining it up more precisely with the other velvet pads.

‘We thought he might have said something to you that would help us find him. He has a medical record of memory loss, and he has been under a severe domestic strain.’

The man took a deep breath, as if coming to an important decision. ‘I know Mr Kosinski. And your sister, too. Mrs Kosinski is an old and valued customer.’

Here was another one who didn’t know that Tessa was dead. So that was how George preferred it. Perhaps he felt he could keep out of trouble more easily if everyone thought there was a Mrs Kosinski who might descend upon them any minute. I let the jeweller think Tessa was my sister; it was better that way. ‘Did he purchase something here?’

‘No, sir.’ For one terrible moment I thought he’d changed his mind about helping me. He looked as if he was having second thoughts about revealing details of his customers. But then he continued: ‘No, he brought something to me, an item of jewellery for cleaning. He said nothing that would help you find him. He seemed very relaxed and in good health.’

‘That’s encouraging,’ I said. ‘Was it a wrist-watch?’

‘For cleaning? No, we don’t service watches; they have to go back to the factory. No, it was a ring he brought for cleaning.’

‘May we see it?’

‘I’ll enquire if it is on the premises. Some items have to go to specialists.’

He went through a door in the back of the shop and came back after a few minutes using a smooth white cloth to hold an elaborate diamond ring. ‘It’s a lovely piece; not at all the modern fashion, but I like it. A heart-shaped diamond mounted in platinum with four smaller baguette diamonds. Quite old. You can see how worn it is.’ He held it up, gripping it by means of the towel. The ring was dripping wet with some sort of cleaning fluid which had an acrid smell. ‘It was encrusted with mud and dirt when he brought it in. In twenty years I have never seen a piece of jewellery treated in such fashion. A ring like this has to be cleaned very carefully.’

‘He didn’t say he was going abroad? His next call was the airport.’

He shook his head sadly. ‘I’m afraid he gave no indication… it seemed as if he was on a shopping trip, doing everyday chores.’

We exchanged business cards. I gave him one of Dicky’s, an anonymous one with one of our London-based outside phone lines on it. I scribbled my name on the back of it. ‘If you remember anything else at all I’d be obliged.’

He took the card and read it carefully before putting it into his waistcoat pocket. ‘I will, sir.’

‘While you’ve been wasting your time, talking to the maid and looking at wrist-watches, I have been thinking,’ said Dicky after I told him what I had been doing that afternoon, omitting the bit about paying for Ursi’s alarmingly expensive facial and manicure.

‘That’s good, Dicky,’ I said.

‘I suppose that analytical thinking has always been my strong point,’ Dicky mused. ‘Sometimes I think I’m wasting my time at London Central.’

‘Perhaps you are,’ I said.

‘Reports and statistics. Those Tuesday morning conferences… trying to brief the old man.’ As if remembering the last time he briefed the old man, he looked at red marks on his fingers which had not completely healed over. ‘He’s here,’ said Dicky like a conjuror.

‘The old man?’

‘The old man!’ said Dicky scornfully. ‘Will you wake up, Bernard. George Kosinski. George Kosinski is here.’

‘In the hotel? You’ve seen him?’

‘No, I haven’t seen him,’ said Dicky irritably. ‘But it’s obvious when you sit and concentrate on the facts as I have been doing. Think it over, Bernard. Kosinski left home without even packing a bag. No one came to visit him; he just up and left the house. No cash, no clothes. How would he manage?’

‘What’s your theory then?’ I asked with genuine interest.

‘It’s obvious.’ He chuckled. ‘Obvious. That bastard Kosinski is right here in Zurich, laughing at us. He’s checked into one of these big luxury hotels, and he’s biding his time until we depart again.’ I said nothing; I knew what was coming; I could read Dicky’s mind when his eyes glittered that way. ‘Our visit here was leaked, Bernard old son.’

‘Not by me, Dicky.’ The reality behind Dicky’s new theory was that his experimental dalliance with investigative enquiries at the airport had been met by airport security men as boorish, obstinate and status-conscious as Dicky could be. Having failed at the airport he’d come back to the hotel to evolve a more convenient theory.

‘By someone. We won’t argue,’ he said generously. ‘Who knows? It could have been some careless remark by one of the secretaries. The Berne office knew we were coming here. They have local staff.’

I nodded. Of course, local staff. No one British must be suspected of such a thing.

‘Tomorrow you can start checking the hotels. Big and small; near and far; cheap and flashy. You can take this photo of him – I pinched it from the drawing-room – and go round and show it to them. We’ll soon find him if we’re systematic.’

‘And which hotels will you be doing?’

‘I will have to go to Berne. It’s tiresome but I must keep the ambassador in the picture or the embassy people will feel neglected.’

‘Dicky, I’m not a field agent any longer.’

‘London staff.’