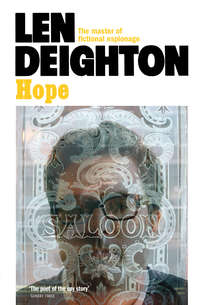

Hope

Now she put her tote-bag on the floor and stood there looking at me again: ‘Room one one one?’ she repeated in English.

‘It’s me, Sarah.’

‘Bernd. I didn’t recognize you.’ She said it without much excitement, as if recognition would only encumber an already burdensome life.

‘Do you want a drink?’ I got a glass from the bathroom.

‘My God I do.’ She pulled off her coat, threw it across the bed, and sat down. As the light of the bedside lamp fell upon her I could see that her hair was greying, and one side of her face was yellow and blue and mauve with bruises that paint and powder could not quite conceal. She poured herself a large measure from the bottle of Johnny Walker I’d picked up at Zurich airport, and drank it swiftly. Poor Sarah. I’d seen a great deal of her after that first meeting. She was studying plant biology and when she went off with her friends, tracking down specimens of rare weeds and wild flowers, I’d sometimes tag along with them. It gave me a chance to get into parts of the East Zone that were forbidden to foreigners. ‘Give me a minute,’ she said, and slipped off her heavy boots to massage her feet. ‘It’s been a long time, Bernd.’

‘Take your time, Sarah.’ She was from the south; a Silesian village in a frontier region that had been under Austro-Hungarian, Czech, Polish, German and Russian army jurisdiction in such rapid succession that none of her family knew what they were, except that they were Jews.

‘Boris couldn’t come. He’s on the early flight to Paris tomorrow.’ She was married to a bastard named Boris Zagan who was a flight attendant for LOT, the Polish government airline. He wasn’t exactly a British agent but he worked for Frank Harrington, the Berlin Rezident, delivering packets to our Berlin office and sometimes doing jobs for London too. I’d heard from several people that he regularly attacked Sarah during his bouts of drunkenness.

‘It’s good to see you,’ I said. ‘Really good.’ There had never been any kind of romance between us; I’d liked her too much to want the sort of on-again off-again affairs that were a necessary part of my life in those roughneck days.

She rummaged through the contents of her patent-leather handbag, found a slip of paper and passed it to me. Pencilled on it there were three lines of writing that I guessed to be an address. I studied it and laboriously deciphered the Polish alphabet. ‘Can you read it?’ she asked. ‘I remember you speaking good Polish in the old days.’

‘Never,’ I said. ‘Just a few clichés. And what I learned from you.’ Poles liked to encourage with such warm words any foreigner who attempted their language. ‘I never was good at the writing; it’s the accents.’

‘Accent on the penultimate syllable,’ she said. ‘It’s always the same.’ She’d told me that rule ten years ago.

‘I mean the writing: the “dark L” that sounds like w; the vowels that have the n sound, and the c that sounds like cher.’ I looked at the address again.

‘It’s a big house in the lake country,’ she said. ‘Stefan, George Kosinski’s brother, lives there. It’s miles from civilization: even the nearest village is ten miles away. You’ll need a good car. The roads are terrible and I don’t recommend the bus ride.’

‘Or the ten-mile hike from the village,’ I said, putting the paper in my pocket. ‘I’ll find it. Tell me about Stefan.’

‘The family are minor aristocracy, but Stefan prospers because Poles are all snobs at heart. He makes money and travels in the West. He even went to America once. He displays great skill at expressing his intellectual pretensions, but not much talent. He writes plays, and all of them conclude with deserving people finding happiness through labouring together. Poems too; long poems. They are even worse.’

‘Big house?’

‘He married the ugly only daughter of a Party official from Bialystok. Boris said the house is vast and like a museum. I’ve never been there but Boris has stayed with them many times. They live well. Boris says it’s Chekhov’s house.’

‘Chekhov’s house?’

‘It’s a joke. Boris says Stefan stole all Chekhov’s best ideas, and his best jokes and best lines and aphorisms, and then stole his house as well. He’s jealous. You know Boris.’

‘Yes, I know Boris.’

She finished her whisky with that determined gulp with which Poles down their vodka, and then studied her glass regretfully. ‘Would you like another?’ I asked.

She looked at her watch, a tiny gold lady’s watch with an ornate gold and platinum band. The sort they sell in the West’s airport shops. ‘Yes, please,’ she said.

I poured another drink for her. If she wanted to sit there and recover, there was little I could do about it, but I wondered why she hadn’t just handed me the address and departed. As if reading my mind, she said: ‘Another few minutes, Bernard, then I’ll leave you in peace.’ She fingered her cheek, as if wondering whether the bruises were noticeable.

Of course! She had bribed the desk who let her in as if she was one of the whores who serviced the foreign tourists. It was a cover, and she would have to be with me for long enough to make it convincing. Something to be hidden is always a good cover for something worse, as one of the training manuals deftly explained. She said: ‘It’s George Kosinski isn’t it?’

‘What?’ I must have looked startled.

‘Don’t worry about microphones,’ she said. ‘There are none installed on this floor. The Bezpieca know better than to bug these rooms. These are where the committee big-shots bring their fancy women.’

‘I still don’t know,’ I said.

‘Don’t go cool on me, Bernd. Do you think I can’t guess why you are here?’

‘Have you seen him?’

‘Everyone’s seen him. As soon as he arrives he shouts and yells and spends his money and gets drunk in downtown bars where there are too many ears. Boris is worried.’

‘Worried?’

‘Has George Kosinski gone mad? He’s swearing vengeance on someone who killed his wife but he doesn’t know who it is. He’s violent. He knocked down a man in an argument in a bar in the Old Town and started kicking him. It was only after he convinced them that he was a tourist that the cops let him go. What’s it all about, Bernd? I didn’t know funny little George had it in him to do such things.’

I shrugged. ‘His wife died. That’s what did it. It happened in the DDR. On the Autobahn, the Brandenburg Exit.’

‘A collision? A traffic accident?’

‘There are a thousand different stories about it,’ I said. ‘We’ll never know what happened.’

‘Not political?’

I went and got another tumbler and poured myself a shot of whisky. At the bar I’d been abstemious but I could smell the whisky on her and it made me yearn for a taste of it.

‘Don’t turn your back on me, Bernd. I’ll start to think you have something to hide.’

I’d forgotten what she was like: as sharp as a tack. I turned to see her. ‘There are political traffic accidents, Sarah. We both know that.’

She stared at me as if her narrowed eyes would find the truth somewhere deep inside my heart. What she finally decided, I don’t know, but she swigged her drink, got to her feet and went to the mirror to put her hat on.

‘Where is George now?’ I asked her. Her back was towards me while she looked in the mirror. She turned her head both ways but spent a fraction of a moment longer when looking at the bruised side of her face.

‘I don’t know,’ she said calmly. ‘Neither does Boris. We don’t want to know. We’ve got enough trouble without George Kosinski bringing more upon us.’

‘I was hoping Stefan or the family might know.’

‘The last I heard, he was scouring through the Rozyckiego Bazaar trying to buy a gun.’ She looked at me, but I looked down as I drank my whisky and didn’t react. ‘You know where I mean? Targowa in the Praga?’

I nodded. I knew where she meant: a rough neighbourhood on the far side of the river. Byelorussians, Ukrainians and Jews lived there in clannish communities where strangers were not welcome. Even the anti-riot cops didn’t go there after dark without flak jackets and back-up.

‘Boris said this is what you wanted,’ she said, bringing a brown paper parcel from her tote-bag and putting it on the table.

‘Have you got far to go?’ I asked.

‘I’m being met,’ she said to the mirror in a voice that didn’t encourage further questions.

I let her out and watched her walk down the long cream-painted corridor. The communist management showed the usual obsession with fire-fighting equipment: buckets of sand and tall extinguishers were arranged along the corridor like sentinels. When she reached the ornate circular staircase she turned and said ‘Wiedersehen’, and gave a wan smile, as if saying a final cheerless farewell to those two young kids we’d been long ago.

After she had gone I thought about her and her bruised face. I thought about the way they had allowed her into the hotel, and let her come up to my room. That wasn’t the way it used to work in Warsaw; they checked and double-checked, and the only kind of girl you could get into your room was a genuine registered whore who was working with the secret police.

And eventually I even began wondering if perhaps Sarah had got past the desk so easily because she was just such a person.

I opened the brown paper parcel. Inside it Boris had put two tyre levers and a looped throttling wire. So he hadn’t been able to get a gun for me; or maybe it was too much trouble. Boris was not the most energetic of our contacts.

‘What did she say?’ It was eleven o’clock in the morning. I’d been out and about. I’d avoided Dicky by missing breakfast, and I could see he was not pleased to be abandoned.

For a moment I didn’t answer him. Just to be back in the heated hotel lobby, where the warmth might get my blood circulating again, was a luxury beyond compare after tramping the streets of the city looking for George and his bloody relatives.

The old place didn’t look so forbidding in daytime. It had been a fine old hotel in its day. A fin-de-siècle pleasure palace built at a time when every grand hotel wanted to look like a railway terminal. Crudely modernized from the empty shell that remained after the war, it wasn’t the sort of hotel that Dicky sought. Dicky was unprepared for the austerity of Poland, no doubt expecting that the best hotels in Warsaw would resemble those plush modern luxury blocks that the East Germans had got the Swedes to build, and Western firms to manage for them. But the Poles were different to the Germans; they did everything their own way.

‘Come along, Bernard. What did she say?’

‘What did who say?’

‘The woman who went up to your room last night.’

I’d avoided him at breakfast, guessing that he wanted me to be his interpreter to interrogate the hotel management. It was not a confrontation I relished, for the interpreters are always the ones left covered in excrement, but what I hadn’t anticipated was that he’d be able to prise from the staff the secret of my nocturnal visitor.

‘It was one of those things, Dicky,’ I said, hoping he would drop it but knowing that he wouldn’t.

‘You think I’m a bloody fool, don’t you? You don’t send out for whores in the middle of the night; that’s not your style. But you are so devious that you’d let me believe you did, rather than confide in me. That’s what makes me so bloody angry. You work for me but you think you can twist me around your finger. Well, you listen to me, Bernard, you devious bastard: I know she was here to talk with you. Now who was she?’

‘A contact. I got the address of George Kosinski’s brother,’ I said. ‘It’s in the north-west and it’s a lousy journey on terrible roads. I thought I’d double-check that George was there before dragging you out into the sticks.’

Dicky evidently decided not to press me about the identity of my lady visitor. He must have guessed it was one of my contacts, and it was definitely out of line to ask an agent’s identity. ‘That’s a natty little umbrella you’re wielding, Bernard.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I bought it this morning.’

‘A folding umbrella: telescopic. Wow! Is this a power bid for Whitehall? I mean, it’s not really you, an umbrella. Too sissie for you, Bernard. It’s just desk wallahs who come into town on a commuter train from the suburbs who flourish umbrellas.’

‘It keeps the snow off,’ I said. Dicky was of course merely showing me that he didn’t like being deserted without permission, but that didn’t make being the butt of his tiresome sense of humour any more tolerable.

‘An umbrella like that is not something I’d recommend to the uninitiated, Bernard. A fierce gust of wind will snatch you away like Mary Poppins, and carry you all the way to the Urals.’

‘But the desk didn’t tell you anything about our pal Kosinski?’ I asked, to bring him back to earth.

‘I left that to you,’ said Dicky.

‘George knows his way around this town. He speaks Polish. He might lead us a dance before we get a definite fix on him.’

‘And by that time he could be on a plane and in Moscow.’

‘No, no, no. He won’t leave until he’s done what he has to do. With luck we’ll get to him before that.’

‘Very philosophical, Bernard. Abstract reasoning of the finest sort, but can you tell me what the hell it means?’

‘It means we can’t find him, Dicky. And there are no short cuts except miraculous good luck. It means that you have to be patient while we plod along doing the things that a village policeman does when looking for a lost poodle.’

This wasn’t what Dicky wanted to hear. As if in reproach he said: ‘Last night, when we first arrived, the reception people admitted that George Kosinski had been here in this hotel. So why won’t they tell us where he’s gone?’

‘No, they didn’t say he had been in this hotel, Dicky. They suggested that we try to find him in another hotel with a similar name. It’s on the other side of the airport. It’s a sleazy dump for overnight stays. He won’t be there. It was just a polite way of telling us to drop dead.’

‘I’ll never get the hang of this bloody language,’ said Dicky. He smiled and slapped his hands together in the forceful way he started his Tuesday morning ‘get-together meetings’ when he had something unpleasant to announce. ‘Well, let’s go there. Anything is better than sitting round in this mausoleum.’ He produced his room key from his pocket and shook it so it jangled.

I was tired after doing the rounds of the city. The official line was that the last of the political prisoners had been released the previous year, but for some unexplained reason all the people given to airing political views the government didn’t like were still serving indefinite detention in a labour camp near Gdansk which had been doubled in size to accommodate a couple of hundred extra detainees. Most of my other old contacts had moved away after the big crack-down, leaving no forwarding address, and my enquiries about them had not been met by neighbourly smiles or friendly enthusiasm.

Now I wanted to have a drink and then sit down to a leisurely lunch, but Dicky was a restless personality, ill-suited to the slow-paced austerity of communist society. I followed his gaze as he looked around with pent-up hostility at everything in the hotel lobby. Its institutional atmosphere was like that of a hundred other lobbies in such gloomy communist-run hotels. The same typography on the signs, and the same graceless furniture, the dim bulbs in the same dusty chandeliers reflecting in the polished stone floor, the same musty smell and the same surly staff.

The skittish way in which Dicky nagged his Department into doing his will was less effective when pitted against the ponderous systems of socialist omnipotence. And so Dicky had found that morning, as he tried to press the hotel manager – and individual members of the staff – into providing him with a chance to search the hotel register for George Kosinski’s name. I knew all this because a full description of Dicky’s activities had been provided to me by a querulous German-speaking assistant manager who was placated only after I gave him a carton of Benson and Hedges cigarettes.

‘I’ll have a quick drink, Dicky, and I’ll be with you,’ I said.

‘Good grief, Bernard, it’s eleven o’clock in the morning. What do you need a drink for at this hour?’

‘I’ve been outside in sub-zero weather, Dicky. When you’ve been outside for an hour or two you might find out why.’

‘Thank God I’m not dependent upon alcohol. Last night I saw you heading for the bar and now, next morning, you are heading that way again. It’s a disease.’

‘I know.’

‘And the stuff they call brandy here is rot-gut.’

‘I can’t buy you one then? The barman is called “Mouse”. Pay him in hard currency and you’ll get any fancy Western tipple you name.’

He disregarded my flippant invitation. ‘Make it snappy. I’ll go and get my coat. I didn’t bring an umbrella but perhaps I can shelter under yours.’

When we emerged on to the street Dicky seemed prepared to yield to my judgement in the matter of avoiding a senseless trek to the hotel’s inferior namesake on the other side of town. ‘Where shall we go first?’ he offered tentatively.

‘I heard George was trying to buy a gun,’ I said.

‘Are you serious?’

‘In the Rozyckiego Bazaar in the Praga. It’s a black-market paradise; the clearing house for stolen goods and furs and contraband from Russia.’

‘And guns?’

‘Gangs of deserters from all the Eastern European armies run things over there and fight for territory. It may look law-abiding but so did Al Capone’s Chicago. Keep your hands in your pockets and watch out for pickpockets and muggers.’

‘Why don’t the authorities clear it out?’

‘It’s not so easy,’ I said. ‘It’s the oldest flea-market in Poland. The currency dealers and black-marketeers all know each other very well. Infiltrating a plain-clothes cop is tricky, but they try from time to time. They might think that’s what we are, so watch your step.’

‘I can handle myself,’ said Dicky. ‘I don’t scare easily.’

‘I know,’ I said. It was true and it was what made Dicky such a liability. Werner and me, we both scared very easily, and we were proud of it.

The Praga is the run-down mainly residential section of Warsaw that sprawls along the eastern side of the river. Most of its old buildings survived the war but few visitors venture here. Running parallel with the river, Targowa is the Praga’s wide main street, the widest street in all the city. Long ago, as its name records, it had been Warsaw’s horse market. Now dented motors and mud-encrusted street-cars rattled along its median, past solid old houses that, in the 1920s, had been luxury apartments occupied by Warsaw’s merchants and professional classes.

Now the wide Targowa was patched with drifting snow and, behind it – its entrance in a narrow sidestreet – we suddenly came to the Rozyckiego market. Overlooked on every side by tenements, there was something medieval about the open space filled with all shapes and sizes of rickety stalls and huts, piled high with merchandise, and jammed with people. This notorious Bazaar had been unchanged ever since I could remember. It had drawn traders and their customers from far and wide. Gypsies and deserters, thieves and gangsters, farmers and legitimate traders had made it a vital part of the city’s black economy, so that the open space was never rebuilt.

‘And are you going to buy a gun too, Bernard?’

‘No, Dicky,’ I said as we went through the gates of the market. ‘I’m just going to find George.’

The ponderous sobriety that descends upon Eastern European towns in winter was shattered as we stepped into the active confusion of the market. Women wept, men argued to the point of violence, whole families conferred, children bickered. And scurrying to and fro there were men and women – many bent under heavy loads – shouting loudly to call their wares.

‘Those communist old clothes smell worse than capitalist ones,’ said Dicky as we made our way through the crowds. Noisy bargainers alleviated the bizarre variety of deprivation that communism, with its corruption, caprices and chronic shortages, endemically inflicts. Here, on display, there were such coveted items as toilet paper and powdered coffee, used jeans in varying stages of wear, plastic hair-clips and Western brands of cigarettes (both genuine and fake). Women’s shoes from neighbouring Czechoslovakia were hung above our heads like bright-coloured garlands, while exotic sable, fox and mink furs from far-off regions of Asia were guarded behind a strong wire fence. Elderly farmers and their womenfolk, enjoying a measure of private enterprise, offered their piles of potatoes, beets and cabbages. A solemn young man sat on the ground before a prayer-rug, as if about to bow his forehead upon the rows of used spark plugs that were arrayed before him.

A tall man in a green trenchcoat stopped me, waved a cigarette, and asked for a light. I tucked my umbrella under my arm, held up my lighter, and he cupped his hands and bent his head to it. ‘I thought you were on the flight to Paris,’ I said.

‘They’ve killed George Kosinski,’ he said hoarsely. ‘They lured him out to his brother’s house, slit his throat like a slaughtered hog and buried him in the forest. You’ll be next. I’d scram if I was you.’

‘You are not me, Boris,’ I said. Tiny sparks hit my hand as he inhaled on his cigarette. He threw his head back, his eyes searching my face, and blew smoke at me. Then with an appreciative smile he tipped his grey felt hat in mocking salute and went on his way.

‘Come along!’ said Dicky when I had caught up with him again. ‘They just want to talk to foreigners. We can’t be delayed by every bum who wants a light.’

‘Sorry, Dicky,’ I said.

By this time Dicky had eased his way into a small group of men who were passing booklets from hand to hand. Two of the men were dressed in Russian army greatcoats and boots; the civilian caps they wore did not disguise them. One was about forty, with a face like polished red ebony. The other man was younger, with a lop-sided face, half-dosed eyes and the frazzled expression that afflicts prematurely aged pugilists.

‘Look at this,’ said Dicky, showing me the book that had been passed to him. It had a brown cover, its text was in Russian with illustrations depicting various parts of an internal combustion engine. Another similar book was passed to him. He looked at me quizzically. ‘You can read this stuff. What’s it all about?’

I translated the title for him: ‘BG-15 40mm grenade-launcher – Tishina. It’s an instruction manual. They all are.’ The booklets were each devoted to military equipment of wide appeal: portable field kitchens, rocket projectors, sniperscopes, nightsights, radio transmitters and chemical protection suits. ‘They’re Russian soldiers. They’re selling in advance equipment they are prepared to steal.’

Dicky passed the booklets to the man standing next to him. The man took them and, seeing Dicky’s dismay, he looked around the group and snickered, exposing many gold teeth. He liked gold: he was wearing an assortment of rings and two gold watches on each wrist, their straps loosened enough for them to clatter and dangle like bracelets.

The hands of the two soldiers were callused and scarred, and covered from wrist to fingertip in a meticulous pattern of tattoos like blue lace gloves. I recognized the dragon designs that distinguished criminal soldiers who’d served time in a ‘disbat’ punishment battalion. Until very recently, to suffer such a sentence had been universally regarded as shameful, and kept secret from family and even comrades. But now men like these preferred to identify themselves as military misfits, defiant of authority. Such men liked to use their tattoos to parade their violent nature, to exploit frightened young conscripts and sometimes their officers too.

‘Let’s move on,’ I said.

‘What were they saying?’

‘Gold-teeth seems to be the black-market king. You heard the soldiers say tak tochno – exactly so – to him instead of “yes”. It’s the way Soviet soldiers have to answer their officers.’