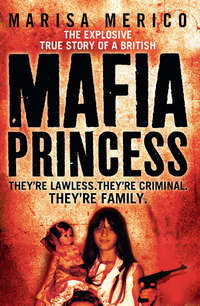

Mafia Princess

They’d been lovers for just sixteen days.

Emilio was delighted and his parents were even more so at the prospect of their first grandchild. Emilio was the adored eldest son and Nan opened the doors of her home to him and Pat.

At that time, Nan’s had two bedrooms, a huge front room, kitchen and bathroom, and eleven kids, aged from nineteen downwards, with Auntie Angela only a few weeks more than a twinkle in Grandpa’s eye. Mum and Dad were given their own bedroom. Nan and Grandpa had the other. The rest had to lump it where they could. It was pandemonium. There were kids everywhere, crying, shouting, screaming, laughing, and they all seemed to be fighting. It was like a coven of hysterical little demons.

‘They’re all mad here,’ thought Pat with a grim grin to herself.

It was all falling into place, as if her destiny was mapped out for her. She had no choice. She wasn’t really in love with Emilio. She was still in love with Alessandro and Emilio was her boyfriend on the rebound. He helped her.

When she was a few weeks’ pregnant she went to Blackpool and told her parents, who were distraught. Where was the man who’d got their girl pregnant? Where was this Emilio? They were horrified, in their quiet, behind-the-curtains English way, at how things had turned out. They had hoped Pat would return quickly after her Italian adventure but she had arrived home to announce she was pregnant and was going back for good to raise their first grandchild. Their big, repeated question was: ‘Who is this Emilio?’

Pat didn’t tell them because she still wasn’t sure herself. Instead she offered: ‘He’s a good man. He’s looking after me. I’m happy.’

And deep down Pat really hoped she would be.

When she returned to Piazza Prealpi, she started getting affectionate with his parents, with all the brothers and sisters, learning much if not all about the family’s history. Her emotions were all over the place, but she wanted to belong, to make it work with the young Emilio and the baby that was on the way. She’d never met a man quite like him before.

‘Better,’ he’d always say, ‘to live like a lion for one day than live like a sheep for one hundred years.’

Yet even in the Mafia, there were questions of propriety. Nan put pressure on Emilio to ‘do the right thing’.

Only eighteen days after I was born, on 9 March 1970, they became man and wife at a registry office close to Piazza Prealpi, with Emilio in a dark suit and Pat in an understated brown dress she’d bought at C&A in Blackpool. Grandpa Rosario, who was a witness, looked as if he was at a funeral. Pat’s parents weren’t there. The wedding reception was pasta at Nan’s.

There, Pat overheard her husband and father-in-law talking in the kitchen.

‘Emilio, I’m worried about this girl. She’s going to ask too many questions. She’s English – she won’t understand how things work. She could really fuck things up for us.’

Grandpa was told there was no problem. No one was going to stand in the family’s way, certainly not Pat. It was business as usual.

As if to prove it, Emilio celebrated his wedding night by going out drinking and gambling with his smuggling crews. His bride spent the night alone, looking after the new baby – me – and worrying about our future.

Emilio was nimble-witted, nerveless and remarkably fluent in violence and villainy. He was an heir to that audacity. Just like his mother.

Nan was born on 14 November 1931 in San Sperato, right by the tip of Calabria, on the Strait of Messina across from Mount Etna in Sicily, as deep in the wilds as you can go. Her family were partisans in the mountains during the Second World War, and ‘partisan’ in their world meant they were fighting for each other, for themselves.

They were infamous. They fought fiercely against the Germans, against Mussolini. They were against anybody and everybody. They quite liked the American soldiers for the black market in chocolate. In their own interests, they dealt in protection, extortion and contraband. It was more ruthless than sophisticated.

They were traditionalists, keeping the faiths of the ’Ndrangheta, whose bad business goes back to Italian unification in 1861. The ’Ndrangheta didn’t need secret codes because the Calabrian dialect is impenetrable. In the early days the poor but proud and angry Calabrians banded together against the rich squires who’d taken over what they saw as their land. There were about 400 people in San Sperato and most families managed to grab a chunk of land.

It hadn’t changed much when Nan was growing up with eleven brothers and sisters, a family bred to war in the Calabrian hills. All of them were crushed into a half-built two-bedroom stone house. The Serraino family, like the others, grew olives and lemons, but they also dealt in contraband cigarettes and liquor, mostly cognac stolen from Calabria’s huge Gioia Tauro port – Italy’s ‘passport to the world’ – which was under ’Ndrangheta control. In the shade of melon stalls on the dirt roads all around the countryside, the illicit booze and tobacco were bought and sold. The police collected their payoffs in kind, bottles of brandy and wine, a couple of cartons of smokes, towards the end of Friday afternoons.

‘Have a nice weekend,’ they were told.

It was the family legacy, the family economics, venal but effective: control the trade, supply the demand, and fear no one. Indeed, keep the authorities close to you, pay them off, corrupt or kill them. The Mafia code: keep your friends close, your enemies closer. Perfection would be everybody on the payroll.

It didn’t always work. Some of the police, not many, were straight, or under some sort of regional government control and obliged to make the occasional arrest. That meant that many of those around San Sperato – for everyone had some connection with the ‘black’ economy – spent at least a short time in jail.

That included my great-grandfather Domenico ‘Mico’ Serraino, who was given six months in Calabria Prison for a robbery in the summer of 1947. They didn’t take into consideration any of his other fifty or so offences – that year – as somehow they were never registered in the paperwork.

Domenico Serraino was known as ‘The Fox’, and was cunning in the extreme. His wife, my great-grandma Margherita Medora, was from a similar family. They were peasants who hadn’t had any schooling. He lived in a narrow world: sons of sons were on pedestals, sons of daughters were undeserving of his attention. The sons of sons were gods but grandchildren with a different surname were not allowed to eat with him. If they came close he would chase them away with the back of his hand. Nan was a blessed Serraino.

It was her job to visit her father Mico in prison, to take provisions, cigarettes and wine. The prison guards would receive their ‘allowance’ during the visit. She was very much a sweet sixteen-year-old in appearance but already wily in the way of a born Calabrian, truly The Fox’s daughter. That gave her the confidence to take a chance on romance with the fresh-faced twenty-year-old prison guard who chatted her up during her visits. There was a real sparkle between them. Rosario Di Giovine was new to the prison, new to the area, but linked by bloodline to the South. His dad worked in Rome in the prison service. It was just after the war and work was hard to find so his dad got him this state job. It most certainly wasn’t a vocation.

Still, he didn’t realise that getting involved with Maria Serraino could get him killed. Just for spinning her a line.

There was no way Nan could take a prison guard home to meet the family. It would be like bringing home the cops. She’d have been disowned and Grandpa would certainly have fallen off a cliff.

Nan found a way. She offered to do the washing for the prison guards in return for a little money. It was an excuse to keep visiting the prison after her father was freed. And Rosario Di Giovine was a quick learner in the ways of Calabria. They kept their affair secret and later my grandpa quietly left the prison service and avoided the cafés and bars the other officers went to. His time there didn’t even stay on his CV. It was as if it had never been. Instead, he became a truck driver, a very useful skill in the Serraino family.

Rosario had a way with him but his charm was tested as Nan’s father and brothers watched closely. In those days you weren’t ever left alone with a man. You had to have an escort. If you went out for an ice cream you had to have a chaperone. That’s how it worked. And it worked double for newcomers like Grandpa. He could feel the eyes on him. But true love always…

As a young couple time dragged for them, so before long they’d run off together to another village in the mountains. The family realised what had been going on and, sure enough, Nan was pregnant.

The atmosphere was difficult, with tension and violent arguments between Grandpa and Nan’s brothers, but circumstances dominated everything. They married and my dad, Emilio, was born twenty days before Christmas in 1949. The Serraino–Di Giovine dynasty had begun and so had the baby production line. While Grandpa became a trusted lieutenant and started driving contraband for the family, Nan began giving birth.

In those tough post-war years, even with all the ducking and diving, the thieving and smuggling, it was an almighty struggle to stay ahead. The ways of Calabria were always respected. My nan was the one who kept everything together and she was always taking in strays, both kids and dogs. She was a lovely, genuinely giving woman, but she had a ruthless streak in her. If you did something bad to her family or disrespected them, she wouldn’t think twice about getting you beaten to a pulp. Just like that she would kick off. That was the world she had always lived in.

When her son Emilio was four years old his grandfather made him watch a pig being slaughtered. The pig’s throat was slit in front of him and the blood dripped into a bucket. This little boy had to immerse his arm up to the elbow in the blood and stir it so it wouldn’t coagulate. There wasn’t room for waste because they wanted to make a batch of blood sausage. Emilio had to keep stirring the blood. That was the side of the family that made him a man. That’s how all the children, the masculine children, as they put it, were brought up.

Kindness to strays and buckets of blood? One extreme to the other.

By 1963, Emilio had six brothers and four sisters and they were all living like chickens, constantly scratching for space and food. It was then Nan decided life would be better in Milan. It was like moving abroad, going to Australia. It was faraway and foreign to them. But Nan packed her bags and her kids and moved north. She had some money saved, and she had guile and single-minded determination. It was enough to get them an apartment on the Piazza Prealpi, which is where La Signora launched her criminal organisation (which was worthy of that title from the start).

She made associations within the Milanese underworld but most important was the established Calabrian connection: from there, at first, came the cigarettes and booze, the currency of her start-up operation. Her gang were a young, wild bunch. Over time all her kids were in the act: Emilio and his tough-guy brothers Domenico, Antonio, Franco, Alessandro, Filippo and Guglielmo. And his sisters, Rita, Mariella, Domenica and Natalina had walk-on parts too. And the ‘strays’ were thankful to help by running errands.

Nan was ever-purposeful; nothing was done by chance. She spoke with a distinct and difficult dialect. It’s very hard to understand – she really needs subtitles – unless you’ve grown up with it. However, her meaning was always crystal clear.

The Piazza Prealpi, fifteen minutes from central Milan on a slow traffic day, was pivotal to her empire. The square housed an assortment of market stalls with flapping awnings and flaking paint where you could buy the fresh basics for breakfast, lunch and dinner. On other smaller but busier open-air stalls there were younger, louder guys selling newspapers, magazines, booze and cigarettes. It was a downbeat neighbourhood of city life and lives. But families didn’t have to go any further for their needs. The cafés, bars and restaurants were open from dawn until the small hours. There were always people about, happier to sit outside than in the squashed, dull blocks of council flats which comprise the Piazza. There was an eager, waiting market for anyone with commercial enterprise, a bit of get up and go.

Nan instantly realised the potential to sell cheap cigarettes and hooky alcohol in the square and make a fortune. She knew that contraband bought in volume and without duty could be sourced and sold much cheaper than it was at present, but still at immense profit.

She didn’t rush at it. She began slowly by selling to the shopkeepers at knockdown prices which became lower and lower, so low that people came from all over the city to buy. She met the demand.

Nan held ‘board’ meetings every morning in her kitchen. Once her children reached a useful age they were told what to steal, how to steal it and who to move it to. Go here. Get this. Do that. Speak to him. Come back to me. If one child ratted on another, told their mother that one of the others had stolen something, the telltale was beaten. Mercilessly. The rule was you said nothing, you kept quiet or the punishment was harsh. The code of silence, omertà, trumped blood bonds. Nan’s law was: ‘You have to shut up.’

Emilio and the others never went to school. Nan was the headmistress, discipline was the whack of a big, stained wooden soup spoon. There was one supreme teaching: ‘First make them fear you. Then they will respect you.’

Nan had few dreads. Maybe God, the Catholic church. I would watch her in the afternoons when she stepped outside the apartment and put her chair out on the street. She would sit there quietly holding her rosary beads and I’d get goose bumps hearing her prayer: ‘God, forgive me for anything I’ve done today.’

Yet, the legend was she knew things before God did. She had eyes in the back of God’s head. She certainly paid him off. The Church was the only place her money went, other than the family and professional expenses. She gave thousands to the Church, perhaps to assuage her guilt. Maybe it was bribery of the Almighty – paying for a place in Heaven? She used to send fabulous clothes (stolen, of course) inside the prisons. She gave thieves heroin: it was a vicious circle. She donated all kinds of goodies to the nuns and priests who worked with the poor in Milan. No one ever asked where they came from, which was just as well. I think it made her feel a bit better inside, that she was balancing things out. None of the family went to confession because everybody thought the priest would have to be paid off to keep his mouth shut. I’m not sure if Nan was bartering with God but she certainly did that with every living thing.

Elsewhere it was cut-throat business. She abruptly axed the legitimate suppliers who had been dealing to the Piazza Prealpi stallholders for decades. It was simple business from both sides of the market stalls. Nan could sell everything cheaper and eventually almost all the shopkeepers and landlords in the Piazza took daily deliveries of knockdown stock.

Supposedly, Grandpa Rosario worked as a regular truck driver. It was a pretty transparent ‘cover’ to prove the family had legitimate income. All that was regular were his trips – over the border to Switzerland where cut-price cigarettes were available.

He and Emilio ran the smuggling syndicate. Emilio was only fifteen years old when he began running a team of two dozen teenage drivers to and from Switzerland with secret compartments under the back seats of their Fiat 500s jammed with contraband cartons. In this way, more than ten thousand packs of cigarettes a day were delivered to Nan’s. When they arrived, crow bars were used to wrench forward the back seats to reveal where the cartons were concealed.

The other legitimate suppliers were severely pissed off. They complained to the police. Uniformed officers felt obliged to investigate and they became regular visitors, always leaving with one or two twenty-pack boxes of Marlboros and a kiss on each cheek from Nan. As word got around the precincts the police faces changed and the gifts became more lavish: expensive jewellery, champagne, a stereo system. She could afford the tempting payoffs.

Nan’s ability to obtain cheap cigarettes and move them on without fuss or interference from the police earned her a reputation across Milan. Soon she became a major fence dealing in all manner of stolen merchandise, whether it was a car radio or a gold Rolex, a cashmere sweater or a used video. If anybody nicked anything anywhere it would go to my Nan’s first. She had first refusal. When someone brought a stolen goat she didn’t blink; she tethered it, fattened it and sold it ten days later. There was nothing Nan wouldn’t buy and nothing she couldn’t sell on at a profit.

And she wanted no competition. If any opposition tried to move in, she dealt with it the Calabrian way. She eradicated the problem. She carved out, literally in some cases, a fearsome reputation. With the police in their pocket it was made very obvious the Di Giovines were the kingpins. The family was devious in many things.Nan hadn’t been educated and couldn’t read or write but she could count money. Very well and very quickly. Nan was the Godmother. People would come to her with their problems and she would help. It established loyalty and connections.

She ran her organisation with military precision and controlled it by military methods. The rules and the consequences for breaking or challenging them were severe. If someone had to be punished Emilio would be instructed, given the assignment. If he was pulling the trigger to whack someone on the street at 11 p.m., it was Nan who had told him where to aim the gun five minutes earlier.

And there was always a beef to sort out. If a rival came into the Piazza trying to deal stolen goods or sell smuggled cigarettes, Emilio would go to sort it. The square belonged to the Di Giovines and my nan’s view was that the bastards had to know who was the boss. Emilio was the Enforcer, dealing out beatings, kicking people to the brink of death. He was short, only 5 foot 4 inches tall, because he’d had a milk allergy as a baby. They fed him tomatoes instead, and the doctors said the lack of calcium stunted his growth. But despite his short stature, no one doubted how deadly he was. He had a reputation for being big down there, well proportioned. His family nickname was Canna Lunga, the long cane. His brothers used to joke about it. He was very good-looking, very charismatic. He just had a way.

When he was younger Emilio wore insteps in his shoes to make him taller. But it was confidence that gave him his swagger on the streets; a brash Napoleon, he did not fear anyone. Idiots would always get one warning to clear out the area but the second time they would get hit.

‘Fuck up a third time and I’ll kill you.’ He meant it.

He got results and his fearless determination to protect and control the area for the family attracted businessmen, shopkeepers and families with their own difficulties. They would go to Nan’s, leave cash and wait for Emilio to solve their problems. With that, the family had one of the most profitable protection rackets in Milan. And if protection duties were slow there was also the flip side, extortion.

‘Maria, these guys keep coming in and stealing stuff off my shelves.’

‘La Signora, some fellas smashed up my bar on Sunday night.’

‘Maria, this guy two blocks down is setting his prices so low I am going to go bust and I can’t buy from you any more.’

‘Send for Emilio’ was the chorus, the solution; going to see Nan meant things were dealt with more efficiently and far quicker than if they went to the police – who Nan was paying to keep their noses out anyway. She had all the ends covered in her kingdom. For Nan this was a gold mine.

However, it meant that my kindergarten was an armed compound and my criminal career began when I was a few months old. That’s when I went on my first smuggling mission. The police have the photographs to prove it.

CHAPTER THREE MARLBORO WOMAN

‘I said blow the bloody doors off!’

MICHAEL CAINE AS CHARLIE CROKER,

THE ITALIAN JOB, 1969

When my mum first moved into the Piazza Prealpi apartment it had been customised for crime. Nan was an exceptionable presence in Milan and despite the payoffs police raids were always a threat. There were compartments, nothing more than holes in the wall riddled around behind the kitchen skirting boards, where Nan kept handguns. There were other hiding places – beneath radiators, in cisterns, at the neighbours’ – for more guns and cash. Many of them were places where only a small child’s arm could reach. She was a female Fagin, my nan.

And her den, the apartment, was a constant bustle. Everyone was asking for more – more tobacco, more bottles of booze, more anything-off-the-back-of-a-lorry, and, always, always, more money.

Mum was dazed by the chaotic and crazed lifestyle; there were usually so many people sleeping over she couldn’t count the number. Names? She was still keeping up with the names of Dad’s brothers and sisters. So from dawn till midnight she just nodded hello when the scores of strangers marched into the apartment carrying boxes. Mum had an idea of what was going on around her but never imagined the scale of it; any questions never quite got an answer. She didn’t push my grandparents; she was grateful for all they were doing for her and for me.

In return for the generosity, Mum helped run the household, working with Nan and Dad’s sisters cleaning, washing, ironing and preparing food. There was always someone around to watch me, play with me. I had all the love and attention in the world.

Mum learned to bake bread, make pasta and create authentic Italian meals, mostly using recipes by Ada Boni, the famous 1950s Italian cookery author. She favoured feed-everybody dishes like Chicken Tetrazzini, a casserole with chicken and spaghetti in a creamy cheese sauce. Nan would be up at six in the morning cooking. In between doing her deals, she was at the stove. We’d wake up to the smell of food. It wouldn’t just be sauces; she would cook all sorts of dishes, including veal, chicken, fish, even tripe. She had a freezer full of meat, polythene bags stuffed with cash hidden among the ice cubes, and boxes and boxes of nicked gear in her larders. She was a regular Delia Smith, but with a .38 revolver in the spice cupboard and a couple of other handguns in the dried pasta. Instead of shopping lists, she would have notebook catalogues of dubious contacts for every possible chore, surrounded by cans of chopped tomatoes. Cooking was her therapy. She never went out. She never did anything. She didn’t smoke, she didn’t drink. Her interests were totally family and business, the Calabrian way. And I adored her. She always had time for me no matter what dramas were going on – and being an Italian household everybody knew about them. You heard them! Very loudly. But even the noise was a comfort to me. It meant that the family were all around and I was safe. It was my warm blanket.

Nan would cook lunch for whoever was there and Mum would be in charge of supper, when there were always at least twenty to feed. Mum felt she was beginning to belong. Her spoken Italian was good but bastardised, using the family dialect, a magicking of Calabrian and Sicilian; she so enchanted the market stallholders when she was out shopping that they called her ‘the blonde Sicilian’.

But she was aware she wasn’t having the same effect on Dad. She’d prayed she would feel the same heart-stopping emotions she had felt for Alessandro. That it would work out between her and Dad. That he would grow out of being a jack-the-lad driven by his lust for new excitement, for girls and fast cars. What she didn’t and couldn’t fully understand at first is what it truly meant to have the blood of the Serraino–Di Giovine family surging through him.