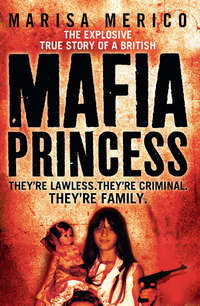

Mafia Princess

Dad had as much regard for that security as he had for the law. He was Mafiosi. He’d been inside for only five weeks when his brother visited him. Francesco is five years younger than Dad but looks like his twin. Dad was fed up with being caged.

He and Uncle Francesco talked for a time and then Dad asked him to change sides at the visiting table, to come over and sit in the inmate’s chair for a moment. And wait. In an instant Dad walked over to and out through the visitors’ exit. The next thing Uncle Francesco was being taken into the slammer, to Dad’s cell.

He pleaded: ‘What’s going on? I’m Francesco Di Giovine, not Emilio Di Giovine!’

Finally, the guards clicked. The brothers had swapped.

‘I didn’t know what he was doing. He was so depressed. One minute he was there, the next minute he was telling me to switch seats. And then he was gone.’ That was Uncle Francesco’s bumbled explanation of Dad’s jailbreak, his stroll out of San Vittore, making him able to celebrate being a free man. At least a free man-on-the-run. Typical Dad.

The prison thought it was a set-up but the only person set up was Uncle Francesco. His story was dismissed and he was kept in jail for three months for aiding a jailbreak.

When Nan heard what had happened she exclaimed: ‘Oh, that bloody son of mine.’ No one knew whether it was praise or criticism.

For the front pages it was: ‘Rocambole a San Vittore.’

As they were writing the headlines, Dad was on a train out of the city. He went south, staying with friends, and then from Rome he made some phone calls. One was to Melanie Taylor, who had returned to England when her Continental dance tour was over.

‘My sweetheart! My love! I can’t live without you! I’m flying over to see you. I must be with you.’

He laid it on with a trowel. It was the perfect escape route, a ready-made safe haven. Dad moved to Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, to link up with Melanie, and got a job at the Huntingdonshire Hotel where she worked. He’d never worked in a hotel in his life, he’d never worked legitimately, but he swiftly moved up the ranks and was appointed assistant manager in charge of a huge staff.

One evening in the bar he got into conversation with Giuseppe Salerno, who was also from Milan. Understandably, they got on well and had much to talk about. Salerno was butler to the Earl of Dartmouth, who was staying with friends in the area. Over the hotel’s fine wine Dad and he became great mates. Salerno would drop in to the hotel when he could, or Dad and Melanie would visit him in London at the quiet and elegant Westbury Hotel in Clifford Street, near the Earl’s Mayfair home. This was the house Giuseppe Salerno ran, and his duties included the security of the silverware storeroom. He had the key to lock it. And unlock it.

Which is what he did on a rainy November evening when the Earl was at a charity dinner.

Dad turned up, they bundled out the silver jewellery, plates and cutlery valued at £30,000. Dad drove off back to Huntingdon leaving his new friend Giuseppe tied up and gagged in the entrance hall. It looked like a perfect robbery.

It was for Dad. Not for anyone else. When the Earl returned from his evening, he found his manservant apparently assaulted and robbed, his family silver out the door. Thieves! Robbery!

Melanie helped Dad hide the silver, wrapped in blankets, in a cellar at the hotel. It would be sold when the heat died down. But Giuseppe wasn’t born to crime. He wasn’t injured, there was no sign of forced entry. To the police it looked as though the butler did it.

Giuseppe tripped himself up again and again during his police interviews. After yet another contradiction, he cracked. He pointed the finger at his fellow Italian and the hiding place of the silver. When the police reached the hotel they confronted Melanie. She wouldn’t say where the silver was and it took them three hours to find it. They never found Dad. He was on the run again. When the Cambridge police ran the name Emilio Di Giovine past Interpol and the carabinieri they got an impressive criminal CV in return.

Yet by the time the case reached the Old Bailey in London on 11 August 1975, their man was long, long gone. But his lover was there. Melanie Taylor admitted ‘dishonestly assisting in the removal or retention’ of the stolen silver.

Judge Gwyn Morris seemed to regard her involvement as some sort of crime of passion. And, because she was acting out of ‘love and loyalty’, he gave her a twelve-month conditional discharge. She spoke outside the court to those bewildered by what had happened to this attractive, sensibly dressed blonde from Middle England.

‘I could not give Emilio away. He told me he was a racing driver. I thought I loved him. I had even got things together for my bottom drawer for our wedding. I was duped. I can’t believe it. I’ll never fall for a Latin lover’s charm again. I don’t want to see him any more.’

She hasn’t. By the time Melanie went back to live with her forgiving parents in suburbia, Dad was enlarging a business in which the value of the silver swag would be petty cash. And he was taking much more risk. Melanie won a stay-out-of-jail card. Dad was setting up drug connections throughout Europe and paying the way with other enterprises.

He was involved with his brother Antonio in supplying stolen cars to Kuwait. Members of their organisation would steal the cars in Spain and then ship them over. Officials at the port of entry in Kuwait were fixed and the cars, all expensive, powerful machines – most stolen to order – would literally sail in.

Unexpectedly, there was a payoff breakdown when a ship full of fifty cars was being taken in. There were problems with the paperwork and a Kuwaiti customs officer was arrested. The Spanish police went to town and finally implicated Dad and my uncle. They were locked away in La Modelo Prison in Barcelona in October 1976. Dad wasn’t going to hang around.

He charmed himself a job in the prison hospital so he could see it how it worked – the hours, the people, guards and regulations – and how he could play it to his advantage, snitch his freedom. He’d made friends with an extravagantly connected Italian inmate, a Mafiosi, and got contacts for a gypsy who could help him in Barcelona if – or, in Dad’s case, when – he got out. For weeks he handed out food, helped with the beds and generally made himself useful as he kept his eyes and ears on the system. He found out that if the prison doctor couldn’t figure out what was wrong with an inmate he was shipped off to specialists at Santa Cru Hospital. With an armed guard. Three officers would escort the handcuffed prisoner, wearing regular street clothes so as not to upset regular patients, on the way for treatment and also guard him at the civil hospital.

Dad got very ill. A mystery ailment. The prison medics couldn’t fathom what was wrong. Off he went to hospital in Barcelona. One officer stayed with the car and the other two lads escorted him into the examination room. While they were waiting for a doctor, one of the cops went out for a cigarette. Still handcuffed, Dad grabbed the other guard and quickly locked him in the toilet. Then he was off. He casually walked down the hospital corridor and out of a side entrance and into the Barcelona bustle. There were people everywhere in the middle of a hot afternoon, 7 July 1977. The seventh day of the seventh month, ’77, four of a kind, 7777, a winning trick. He says he felt like Houdini.

And Dad’s luck held, for as the bulls began running in Pamplona that day, he took a long route to Milan. All he had on him was one of the tiny keys you got on cans of corned beef. Dad employed that for all sorts – Fray Bentos robberies, if you like. He’d open every possible lock with those keys, and his speciality was cars. With these tricky little things he’d get a car unlocked quicker than most people could open the can.

Within a few minutes he’d jumped in a taxi and ordered it to drive to the Plaça de Catalunya, which is the busiest square in the city. He had no cash and was hiding his handcuffs so he asked the cab driver to wait while he made a phone call. He ducked into the subway and came out on the other side of the plaza, from where he could see the taxi waiting. He also saw lots of police movement. He went into a toilet and picked the lock on the cuffs. It took a moment. In the street he brazenly stopped a young woman and asked if she’d help him, let him sleep at her house, but she wasn’t having any of that. Imagine! He thought his smile would be enough.

He persuaded a beggar to give him some loose change to call the gypsy contact, but there was no reply. There were a couple of Italian warships in port at Barcelona and he heard a sailor with a Calabrian accent asking for directions. Dad gave him a cock and bull story about being stranded in the city and the lad gave him a load of pesetas. Everywhere he went, he somehow talked people into helping. It was getting dark.

He chanced his luck on the last bus to the outskirts of Barcelona, a trip on which he might or might not be checked. It held again. And good fortune was his once more when he found a minibus at 3 a.m. He clicked it open with his corned beef key and had a couple of hours’ kip.

But even though it was July, the winds were howling, plants were jumping off balconies and the van was rocking. It was early morning when he got to La Rambla pedestrian mall in central Barcelona, but it was packed with tourists who provided people cover. It was before 8 a.m. when he rang the gypsy, who said he’d just got in from his evening and to call back at 1 p.m.

‘Hang on a minute! Look, pal, this is an emergency. I’ve been told you can help me…’

He told Dad to come round, get this bus, do this, do that, take another bus, do that. The front door was opened by a Spanish gypsy who looked like a flamenco dancer. When he and his wife realised who Dad was – his picture was all over the telly – they treated him like a king. They couldn’t do enough for him. This guy did robberies and Dad, the legendary ‘Lupin’, was one of his heroes. The guy showed him what he’d nicked, including some gold bars. While Antonio was stuck in jail and the cops searched land, sea and air for Dad, he put his feet up with them for a week. He rested and plotted.

He always found a way to do everything. There’s nothing that can’t be done by my dad. A fake passport was arranged from Italy, and when it and money arrived he moved on. He took a plane from Barcelona to Madrid and then a train to Malaga and a taxi to Algeciras. From there he took the ferry to Tangiers, where he fell in with a Neapolitan–Moroccan man who entertained him while he waited for three days for the first plane to Rome.

His trail was complex but cold. A bodyguard-driver met him at Fiumicino Airport and they drove back to Milan, which with my family’s efforts was developing into one of the world’s most important drug-trafficking junctions. In tandem, the European ‘Di Giovine Connection’ was operating. It was a family business run from Piazza Prealpi, their estate, their fiefdom. My Auntie Natalina’s husband Luigi Zolla was appointed by Nan as ‘manager’ of the Piazza.

It was recognised, if reluctantly accepted by rival drug organisations, that the Di Giovine family had majority control. Drug suppliers dealt directly and exclusively with the family or there would be trouble. When one of the family’s dealers attempted to set up business for himself, Nan issued only one instruction: ‘Kill him.’

He was murdered within twenty-four hours.

Another dealer didn’t learn that lesson and tried to edge into Di Giovine territory. He died too.

The notoriety increased with the viciousness with which the family’s dominion was protected. Intrusion was not tolerated. Business had to be protected, no matter what.

When Dad’s sister Rita was sixteen years old, she was living at Nan’s with her boyfriend and they started dealing heroin. When thieves brought stolen TVs and other plunder to be fenced they used the money Nan paid them in the kitchen to buy smack off Auntie Rita in the bedroom. It was a clever crime carousel. But there was a big bust-up between Rita and her boyfriend. She was weighing the heroin and cutting it with sugar to make it go further. She didn’t see that as a rip-off. But she didn’t like it that her boyfriend was short-changing their buyers by putting less than the correct weight of heroin mix in the drug packets.

Rita was never Nan’s favourite. She was too needy, too eager to please, and Nan didn’t respect her as a result. She preferred the kids who spoke out and gave the finger to authority. She didn’t always treat Rita terribly well because of this, and when she found out what Rita and her boyfriend were rowing about she went ballistic. She didn’t want anyone in the middle. She wanted total control. After that when the druggies brought stolen goods she paid them in heroin, cutting out her own daughter.

Like a medieval warlord, Nan had an official taster-tester. Only in his teens, Mimmino, who lived out back in a lean-to, wasn’t employed to check the family food for poison but the strength of the heroin. His reaction to his fix would dictate whether the batch could be cut for more profit. A risky business, and he eventually died from an overdose.

There was so much heroin being packed, unpacked, cut and doctored at Nan’s that a couple of neighbours, women who allowed her incoming calls on their untapped phones, were convinced their dogs were being affected, getting high on the aroma and behaving very oddly. In the mêlée of daily life no one else noticed, just gave a shrug when it was mentioned. The dogs seemed content.

Dad was making more connections with the Turkish gangs who were a developing influence in Milan. They operated easily in the shadow of Italy’s kidnapping epidemic in the years after the profitable snatching of John Paul Getty III. The kidnappers targeted kids from rich families and many of the victims were never seen alive again. In 1976 more than eighty men, women and children were held to ransom. The kidnap and murder of Aldo Moro, the two-time Italian Prime Minister, in 1978 remains an open wound for Italy. But with all the scrutiny and risks and no guaranteed profit, kidnapping wasn’t a business my family wanted to move into. Drugs were the future. Yet there’s always friction, with other organisations wanting to expand in the same line of business. It’s impossible to grow without taking up space that others believe belongs to them. There were plenty of ‘others’.

Dad was mixing with a lot of evil people. One sinister gang, nicknamed Kidnaps Inc, was responsible for grabbing twenty-one hostages, three of whom vanished for ever. A Yugoslav called Francesco Mafoda was one of the leaders. He understood Dad’s contacts and influence and tried to recruit him into the organisation. This guy wasn’t just ruthless and mean; he was borderline psychotic. His unsmiling, pockmarked face was a signal he wasn’t a good bet. Dad said no.

Mafoda didn’t like being turned down but Dad was his own man. And a free one. Nan had paid off a judge from a new bank account in Marbella, to finally get the prison swap charges dismissed. Dad fobbed off Mafoda and concentrated on the drugs business. And keeping business in the family. Along with his brothers and sisters, Dad controlled teams in Milan dealing with the Turkish shipments brought in by road, kilos and kilos of heroin often hidden in giant canisters of cooking lard. Week by week the number of trucks, buses, consignments and millions of dollars involved grew and the heroin distribution crews took on new sales teams to spread the deadly but so lucrative product.

For Dad, it was a wonderful world. And something surprising had happened in his life. He was in love. Adele Rossi was only sixteen years old when Dad started dating her. He adored her. She went everywhere with him. He guarded her, looked after her, loved her. They went around hand in hand. They were always touching each other. Not in a sexual way but as though they were making sure the other one was still there; seeing wasn’t enough. She met Mum and me and we liked her. She was lovely, a joyful personality. And beautiful, with long legs and a cascade of blonde hair. Everyone noticed how happy Dad was. He was even happier when Adele got pregnant. And I was delighted, and nervous, at the prospect of having a sister.

In this absurd world, Mum, estranged and separated from her husband, was also trying to have a romantic life but Dad’s power and personality were an ongoing obstruction. He didn’t want to be with Mum but he didn’t want anyone else to be with her either. It was ridiculous but so common in broken relationships. Dad didn’t love Mum in that way, didn’t want to be with her, but was jealous at the thought that someone else might pay her attention.

Some confused and irate husbands might make idle threats if any other man got close to their wife, estranged or not, but with Dad it would have been action not threats. With him so close by, how could Mum ever find happiness again? What man would want to be with her and play surrogate daddy to his little girl when he knew Dad was around the corner? One guy, Gianni, decided he couldn’t live with the risk of reprisals for getting close to Mum and me, and he broke off their relationship.

Mum did see other people, including one guy who was a friend of the family so they had to keep him all hush-hush from Dad. One night he stayed over at the Mussolini flat with its one big room with one big bed. Mum slept on one side, I slept in the middle, and this guy was on the other side. I was seven years old and slept in pyjamas. I didn’t have any underwear on. I woke up in the middle of the night and this guy’s hand was between my legs, on me. He wasn’t messing. It was just there. Plonked on it. What could have happened if I hadn’t woken up? I was lucky he didn’t do anything more.

I pushed his hand away and cuddled up to Mum. I never told anybody. What if I had mentioned it to Nan or my dad? Well, Mum might not be alive. I’m not kidding when I say that. Dad would have taken me from her, chopped the guy’s hands off and killed him.

I can’t condemn Mum. She only wanted some personal happiness, as did Dad, but both in their own ways. Yet Dad had changed. Breaking his own rules about business and pleasure, for that’s all that women had meant before, he took Adele along to his meetings. One evening, on 2 October 1977, he got a call about a heroin shipment worth around £50,000 to the family; nothing to be concerned about, a simple distribution deal. He arranged to meet the contact man, Vittorio Bosisio, at a local coffee shop to make the arrangements for the next day’s delivery.

Unknown to Dad, Vittorio Bosisio was a dead man walking. He had run up hard against a brutal, no-nonsense Yugoslav called Mimmo Pompeo who carried machine pistols like cowboy six-guns. Bosisio hadn’t paid off on a drug shipment and Pompeo issued an order to take him out. But Vittorio Bosisio, hard-faced and streetwise, was crafty and had kept himself alive for three months. Now he needed money, needed a deal. And someone tipped off the Slav where he’d be that evening at 9 p.m.

No one knew that Dad and Adele would be there too. They and Bosisio ordered three double espressos, water and a biscotti each on the side, and were talking quietly when the first spray of automatic fire riddled the windows. The Slavs were determined Bosisio would die. There were eight gunmen firing from behind a line of parked cars. A thunderous rat-a-tat sounded as bullets howled into the cafe. Vittorio Bosisio took the full blast of the assault and his body was punctured from head to toe.

Adele tried to escape by running out of the front door but she rushed headlong into the guns. She was shot in the head, killed instantly, spilling on to the pavement. She’d just turned seventeen years old and was three months pregnant.

Dad acted instinctively, turning his body and throwing his hands up in front of himself, trying to block the gunfire. A barrage of bullets caught him in the arms and legs. The blood spurted and he collapsed onto the tiled floor in a coma, near death.

When the police teams arrived, they arrested him.

CHAPTER FIVE GUNS AND ROSES

‘In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity.’

ALBERT EINSTEIN

Dad woke up with flowers and a detective by the side of his hospital bed. The investigatore di polizia was there to see that no harm came to him. The flowers were from Mimmo Pompeo, who was concerned about his own protection since he had ordered the shooting. Adele’s death and Dad’s almost-fatal injuries were collateral damage. He and young Adele were not meant to have been there. The floral arrangement was a message of apology.

Sorry for killing your pregnant girlfriend.

Sorry for shooting you full of holes.

And, probably, sorry for not finishing you off. Which would have happened if not for emergency surgery and clever doctors.

The police didn’t have to think like Sherlock Holmes to realise that, when he fully recovered, a bunch of roses wasn’t going to be enough to calm Dad down – he wanted revenge. Vendetta? He wanted a massacre. Adele was the love of dad’s life. He was devastated by her violent death.

On the front pages were photographs of her blood-soaked body splayed across the ground, a pregnant, teenage victim of mobster gunplay in central Milan, and it made provocative and controversial news. It sparked heavyweight political pressure from Rome. This was a national scandal. Something had to be done, lessons learned, the usual useless political claptrap.

Still, with Rome on their backs, the authorities in Milan were determined to prevent open warfare between the Yugoslavs and the Di Giovines. They wanted no more bodies on the streets, no further voter-upsetting mob mayhem in the newspapers.

They’d arrested Dad in the aftermath of the killings and now they charged him with a string of old robberies and burglaries. They dug up anything they could from the unsolved files to convict him, to stop revenge shootings by getting ‘Lupin’ off the street. They had him bang to rights on the robbery of furs and artwork worth several hundred thousand pounds from Countess Marzotto Trissino’s villa near Verona. He wasn’t happy about that. Unknown to Dad, his brother Francesco had photographed the proceeds of their burglary and sent the snaps to the Countess demanding a ransom. That wasn’t smart, and the enraged Countess immediately blew the whistle. Dad and Francesco were identified as thieves, so there was one genuine problem in the long but generally token charge list waiting when he was carried into court on a stretcher and laid out next to the dock.

I was seven years old, but that moment is a locked memory card. It was scary for me at the back of the courtroom where I sat with Nan. I kept grabbing her hand. She kept telling me quietly not to worry, not to fuss.

Dad had a beard and long hair and was on a stretcher wearing a white gown covering his bullet-punctured body. It was the first time I had seen him since the shooting.

He looked like Jesus. Appropriately, for the plan was to crucify him.

He was so red-eyed and pale and lost-looking, I wanted to jump over the wooden railings and get to him. I just wanted to hold on to my dad. I never wanted to lose him. It was then, at that moment, when I was seven years old, that a lifetime love, a precious bond, was forged. There was a strange, psychic thing. He hadn’t made eye contact with me up to that point, but then, as my emotions were boiling over, he looked straight at me. While the judge was sentencing him to return to San Vittore prison for a year, Dad smiled and blew me a kiss.

As he was stretchered from the courtroom by two armed guards, he craned his neck and gave me another smile, blew a second kiss and mouthed: ‘Spiacente [sorry].’

I was no longer just his little princess. I was his Mafia Princess. I would do anything for him.

Nan murmured to me: ‘Don’t worry.’

She could afford to be relaxed. She knew there wasn’t going to be too much hardship. She had made arrangements for Dad to have his favourite foods in jail and any wine he wanted. He’d also have drugs and cigarettes, but not for his own use – he never touched them. The cigarettes were the pennies and pounds of prison, dope of any kind the top currency, to barter and bribe.