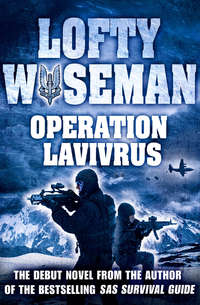

Operation Lavivrus

Knowing that he was parachuting in the morning always affected him this way. So many things could go wrong: hard pull, malfunction and mid-air collision were all distinct possibilities. A bad spot could cause you to land in water or hit power lines; landing on the DZ with equipment was bad enough as it was. In one part of his mind he hoped that the jump would be cancelled, but he also looked forward to the challenge.

Everything was his responsibility; the colonel had made that quite clear at their last meeting. He was told he had to take charge more, and not leave everything to his Staff Sergeant. He couldn’t help thinking of Tony again, and their fight.

He tossed and turned, trying to switch off his overactive mind. Just when he was on the verge of sleep an explosion of light would pierce his tired eyes, bringing him fully alert and leaving a myriad of dancing lights bouncing around his skull. There was no escape; the more descents he had done, the worse it got the night before.

All too soon the alarm clock went off. He arose from sweat-soaked sheets.

Conversation was non-existent in the minibus, and the early start was only partly to blame. Parachuting always had the same effect, and most people wanted to be quiet. They feigned sleep, reliving past descents, mentally going through a checklist: good strong exit, stable fall, smooth opening, lower equipment, feet and knees together for landing.

They never knew until the last moment whether the jump was on or not. The weather seemed good, but it could change in an instant. They were jumping in Wales near the mountains, and the weather here was unpredictable. The C-130 rarely became unserviceable, but it did happen. The ground party who manned the DZ had the last say. If they gave the thumbs up, the jump was on.

Every descent was different, and if you were unprepared you could get caught out. All these men were experienced, however, and left nothing to chance. They always went through the same rituals and mental rehearsal.

Chalky – Lance Corporal Henry White – a veteran of more than 1,000 jumps, had broken his tibia and fibia the last time he jumped on Sennybridge. This was a freak accident that happened eight months ago. A gust of wind caught him as he was about to land, causing him to fall heavily on a trip flare piquet that had been left behind by some irresponsible unit. He was now fully fit, but he sub-consciously flexed the old injury, trying to reassure himself that it wouldn’t happen again.

Chalky was of mixed race, and had endured plenty of malice and racial abuse as a child growing up in the East End of London. His father was a West Indian seaman who met his mother at the Stepney General Hospital, where he was taken sick after a voyage. She was a nurse there, and fell pregnant after a brief affair. He sailed away, promising to return, but he never did. He was never seen or heard of again. Coming from a religious family, his mother was ostracised for bringing disgrace to the family. She was cast out and had to fend for herself. She had to work, so Chalky was passed around among the few friends she had left. Sometimes she had to take him to work at the hospital, where he was hidden in the laundry or looked after by a porter.

It was a tough community to grow up in without a father. His mother suffered endless abuse from bigoted neighbours, and Chalky couldn’t wait to be big enough to defend her. Although she doted on him, he was a painful reminder of the past, and joining the army was a natural escape for him. He fitted into his new family well. At twenty-seven years old, with seven years in the Squadron, he was the troop medic, probably influenced by his mother.

Fred massaged the scar on his leg where he had been burnt hitting high-tension cables three years ago. It seemed like yesterday that the brilliant blue flash lit up his body and the surrounding area of Salisbury Plain. Cables are difficult to see from the air, even in daylight. The parachute collapses when the cables are touched, leaving the parachutist to fall to the ground. Electrocution is the lesser of the two hazards.

Tony’s main concern was the insertion phase of the coming operation. Stretched out on the seat with his hood up and arms buried between his thighs, he thought about deception plans. Any aeroplane entering another country’s air space is immediately challenged. It is acquired by radar, and unless it gives the correct response aircraft are scrambled to intercept it. In a time of conflict the plane may be shot down. The Argentinians had a good air defence system, and intelligence was trying to get up-to-date info on its performance and limitations. A modern system like theirs acquires the target, and unless it is identified as friendly it fires an anti-aircraft missile. Tony’s problem was how he could make his aircraft appear friendly.

He pushed this to the back of his mind, concentrating on the problem at hand. He was responsible for lining up the aircraft and getting it over the exit point. The RAF navigator would get the aircraft on the run-in track at the correct altitude, then it was up to Tony to eyeball it from the ramp, getting them over the release point.

The parachutes they were using were twelve-cell steerables with reserves to match, on a piggy-back system. These were state of the art and only available to the Regiment. They had a good performance, capable of holding a 20-knot wind, and if need be they could cover a lot of ground. This was fine if you could see where you were going, but at night you just wanted to land gently, and a high-performance chute could get you into trouble. These were definitely not for the novice.

On a night descent it is an advantage to have some moonlight with a little cloud cover. On all but the darkest nights the ground can be seen until the last 1,000 feet, when the earth is enveloped in shadow. Their jump was scheduled just before first light; they would catch the end of the old moon, making conditions ideal.

No visual aids were being used on this descent; if they could be seen from the air they could be seen from the ground. 3 Troop were already deployed in the area to test the effectiveness of the covert entry; they would dearly love to capture a 2 Troop birdman and pluck him of his feathers. Inter-troop rivalry verged on the sadistic.

For safety reasons a ground party was in the drop zone in radio contact with the aircraft, but neither displayed or gave signals. Their sole job was to keep an eye on the ground winds in case they exceeded the limit, and provide medical cover.

The lads came alive as the bus turned through the large ornamental gates of RAF Lyneham. Security was impressive, the area being well lit and guarded by RAF police who waved the bus through. Sandbag emplacements had been built to dominate the approaches to the base. Tony took particular interest in these security arrangements; he would soon be trying to breach similar defences.

There was some small talk on the short journey to the hangar, the sleepy atmosphere transformed into a lively scene as people stretched and chattered. Past exploits were discussed, and misfortunes recalled. ‘I remember carrying Chalky . . .’ ‘Fred put out all the lights in Salisbury . . ..’ The men were in good spirits, ready for the descent.

The navigator gave the lads the flight briefing. His ruffled hair and bulbous eyes reminded Tony of a rabbit caught in a snare. His tired, monotonous voice confirmed his dislike of early starts, and he made an exciting event seem dull. He yawned continuously as he pointed to an enlarged aerial photograph of Foxtrot Charlie, and traced the run-in track using a black china graph pencil.

‘The wind at 18,000 feet is at 230 degrees steady at 35 knots. This changes to 200 degrees at 8,000 feet, slowing to 20 knots. Opening height for this sortie is at 3,500 feet with the same wind but at 190 degrees. Ground wind,’ he paused for an infectiously long yawn, ‘is 8–10 knots.’ Tony couldn’t wait to take over the briefing and inject a bit of spark.

‘We calculate the release point here and the opening point here.’ The navigator circled two red points on the photo. ‘I will get you to this point here, and Staff, you will take over when the red light comes on. You should see this lake clearly, and all this forestry will stand out.’

Charlie was picking his teeth with a broken matchstick, removing the traces of a kebab he had the night before. All this talk of knots and degrees went over his head; he just wanted to jump and follow the others.

Eyeballing a C-130 at night is not easy. Tony’s job when the red light came on was to get the aircraft exactly over the release point. Staring into the slipstream from the ramp is the most accurate way of lining up an aircraft. Peter and Tony confirmed the navigator’s calculations to verify the checkpoints. They added the final details to the air briefing Peter was going to give.

The cavernous interior of the aircraft looked even bigger with only eight men sitting in the middle. They sat either side of an oxygen console, fully dressed, strapped into webbing seats, with bergans (rucksacks) held between their legs. It was only a short flight so they wouldn’t have time to strip off or stretch out.

Aircraft have a smell of their own, a heady mixture of cold alloy, warm nylon, hydraulic fluid and paraffin. Soon the tantalising smell of RAF coffee would add to this rich bouquet.

Conversation was made difficult as the high-pitched whine of the four turbines increased. As the noise level rose, so did the vibrations. Tony watched, fascinated, as the safety ring of a fire extinguisher revolved slowly, and a discarded polystyrene cup did a dance of its own until Fred crushed it under a size 10.

With engines running evenly, the aircraft lurched forward as it began to taxi out to the main runway. The big Herc rolled and swayed like a ship in heavy weather. They were wasting no time this morning and rumbled forward, turning sharply onto the threshold. It dipped down on its undercarriage as the brakes were applied, and the passengers braced themselves for take-off.

A whirr of hydraulic pumps set the flaps as the engines ran up to full power. Raring to go but held back on the brakes, the whole structure shuddered. When the brakes were released the huge camouflaged aircraft leapt forward like a spirited stallion, building up speed rapidly before soaring up into the early morning sky.

Once it was clear of the ground the pilot eased the throttles back as they climbed steadily to 18,000 feet. Seat belts were undone and the loadmaster came round with the traditional RAF coffee in polystyrene cups. To the old and bold this was the worst part of the jump.

As they sipped their strong, sweet brew they were given an altimeter check. Each man had two altimeters, and they carefully calibrated then both. Through nervousness rather than necessity, they tapped them to ensure the needle wasn’t sticking.

A dull red light was the only illumination in the aircraft, set above the oxygen console. It didn’t affect night vision, but it cast an eerie light over the eight men huddled in the centre of the cargo hold, like witches around a cauldron.

Twenty minutes before P hour they plugged into the console and the aircraft depressurised. All too soon the rear ramp was lowered and the stale air was immediately purged by an invading blast of cold air. Loose webbing at the rear of the aircraft flapped around in torment. Everyone’s ears were affected by the change in pressure; the men cleared them by holding their noses and blowing. They got ready, ensuring their weapons were secured down the left-hand side. Next they secured their bergans, attaching the lowering device to the harness.

Five minutes before P hour they unplugged from the console and plugged into the small oxygen bottle they carried on their harness, before waddling to the ramp for an equipment check. They kept their goggles up to save them misting, and checked each other’s chutes. Only hand signals could be given as their oxygen masks covered the lower face. Their bergans were carried behind the thighs, connected to the harness with quick-release hooks. When everything had been checked they followed Pete, who was Mother Goose – where he went his chicks would follow. He led them to the ramp where Tony had his head stuck out in the slipstream.

Holding on with one hand and giving corrections with the other, Tony was bringing the aircraft on track. Each motion with the open hand was a five-degree correction to one side or the other; the loadmaster, who was secured to the ramp by a monkey belt, relayed Tony’s signals to the pilot.

Five degrees left, steady. Five degrees left, steady. Tony could make out the lake and the distinctive forest shape that he recognised as the release point. When he was satisfied he stood up and pointed to the green light. The red light went out and the green one came on.

Bunched on the tailgate, eager to go, the lads kept a finger under their goggles to keep them clear. They were now bathed in green light, looking like aliens from outer space. Tony gave the thumbs up, and was gone.

He felt free; there was no more weight hanging from his shoulders, and his aching back was now supported on a cushion of air. Engine noise was replaced by a rush of cold air which lightly buffeted his body. He looked around, and above him he could see seven more bodies in formation like bulky frogs hurtling earthwards at 120 miles per hour. ‘What a way to make a living,’ he thought.

He could make out several lights below him from scattered farms, and could picture the cosy scenes within. Directly below him was a large pine forest which he recalled from the air photograph. Standing out was the silver thread of a river that ran alongside the wood, and a duller line of a road that ran across it.

They were a little deep, if anything, so he swept his arms back and straightened his legs, tracking towards the opening point. He was the low man and the others would follow him. His head-down position increased his speed, causing his cheeks, which were compressed by the oxygen mask, to flutter. He flared out again, checking his altimeter, which was unwinding fast, the luminous dials giving him a clear picture.

At 4,000 feet he brought in his right hand to grasp the handle of his ripcord, waving his left arm out in front of his head to warn the others of his intention. At 3,500 feet he pulled the ripcord, instantly feeling the retarding effect as the drogue came clear of his body and started extracting the main canopy. The rigging lines deployed first, allowing the sleeve which sheathed the canopy to peel off; this eliminated a lot of the opening shock. As the canopy caught air it inflated with a dull ‘crump’, breathing one or two times before remaining fully inflated and stabilised.

Tony looked up and checked his canopy before carrying out all-round observation. He had lots of time to do this today, as normally they open their chutes much lower, but at anything lower than 3,000 feet the opening noise of the canopy could be heard from the ground.

Pulling down on his left toggle, Tony turned to watch the others deploying. One after another, the chutes popped open, slowing rapidly, but the seventh shape was distorted, hurtling past the others. Instead of a symmetrical shape an untidy bundle of material streamed behind the tumbling figure, disappearing rapidly as it merged with the earth’s shadow.

Tony landed softly and ran round his chute to collapse it quickly. He ripped off his gloves before removing his helmet, goggles and mask, all in one rough movement. After a quick look around he exaggerated a yawn to help clear his ears so he could listen out for the others. He removed the sling from his weapon and laid it down while he took off his rig. After stripping the carrying straps from his bergan, he stowed the chutes and parachuting equipment inside a large para bag which they carried for this purpose as it helped speed up deployment from the drop zone.

With practised efficiency he was ready to move in under ninety seconds, loaded up with the para bag balanced on top of his bergan, heading off to the RV.

‘I wonder who was tumbling,’ he thought as he opened and closed his mouth, trying to get rid of the waxy film that blocked his ears. Finding the gap in the hedgerow he had been heading for, Tony waited impatiently for the others to arrive. ‘Hurry up, lads. I can’t go and look until someone comes.’

Chalky was the first to arrive, followed closely by Fred. Tony told him to hold the lads at the RV while he and Fred went to find the low man. He knew roughly where to look, recalling the tragic sight of the figure flailing directly over the opening point. He was dreading what he would find. The troop had suffered two fatalities and he had witnessed both of them.

Ron was a former Green Jacket. He had been shocked to find that he had passed selection to be posted to a free-fall troop. His first love was water, and a boat troop would have been his ideal choice. Being new, he couldn’t argue, and knuckled down to learn what he called this terrifying skill. He couldn’t understand the casual approach of the old sweats. It wasn’t bravado: they actually looked forward to the next drop. He fought hard to control his fears, thinking things would get better, but each descent was worse. Being young and enthusiastic he hid his fear well, covering it with a sense of humour that convinced other troop members that his apprehension was faked.

He was last man in the stick, which was where they placed the least experienced member. What little confidence he had was sucked out of him when the ramp was lowered. Looking at Tony hanging precariously around the side of the plane with the slipstream tearing at his face made him physically sick. Being bathed in the red light while he huddled on the ramp was his vision of hell. He couldn’t take his eyes from his altimeters; he didn’t want to see anything else. He was aware of the light turning to green, feeling the change in air pressure as the team dived into space. Then he was alone. His training took over, forcing him to stagger forward and tumble over the edge.

Hammered by the slipstream, his asymmetrical form was immediately sent spinning, toppling him end over end. Calling on his limited experience of thirty-nine descents, he corrected the tumbling once he relaxed and stopped flailing his limbs. But the tumble had shifted his load, making stability difficult and forcing him into a left turn that quickly built up speed. His equipment was hanging to the left, causing him to overcompensate, and before he realised it he span violently in the other direction. He reached terminal velocity in ten seconds, and the gyrations increased to blood-surging speeds. His eyes were riveted to his altimeters, forcing his head down, which added to his plight. Trying to terminate the descent he came in early for his handle, which flipped him onto his back, tearing off his goggles. Even with his eyes stinging and swimming in fluid he refused to close them, staring at the altimeter needles’ relentless progress towards the zero mark. The discarded goggles battered his helmet, threatening to crack it open. His head pounded as he hurtled earthwards out of control, with a mask full of saliva which bubbled and frothed as he screamed.

He should have spent more time sorting out the spin to ensure a clean deployment, but panic had taken over. Maintaining an arched back with head up would have restored stability. He ripped the handle from its housing and pulled. Instead of the familiar opening shock, a vicious pain shot across his chest and arms, but the pressure on his eyes eased immediately. The chute had deployed, slowing him down, but rigging lines had been thrown around his body and over the canopy, preventing full development. Falling feet first with a bundle of washing above him, Ron fought for air. The pressure across his chest was immense, and with his arms securely locked to his body breathing was difficult. For the first time he stopped looking at his instruments and focused on the red handle of his reserve, which seemed a million miles away.

Different thoughts flashed through his mind and everything now seemed to be in slow motion. ‘Nobody really cares for me. No one is going to miss me. Not many people know what I’m doing or where I am. Now I’ve let my mates down. I am a failure.’

Light years of falling took in reality only seconds. One part of him was saying ‘ relax’ and promised comfort, while the other screamed for him to make the effort to reach the reserve handle. Survival instincts are strong, and the screaming won. With a determined effort, aided by adrenalin, he went for the handle. But every time he moved, more pressure was put on his chest, threatening to asphyxiate him and increasing the pain in his arms. He desperately wanted to get back on terra firma, but not this fast.

He was still gyrating, but at a slower rate, the bundle above him retarding his fall. The danger now was that, even if he reached the handle and deployed the reserve, it might become wrapped around him. The normal drill was to cut anything above you away, but he was effectively a prisoner in his own harness.

Sheer determination, engrained in him by his army training, paid off. A Houdini-type effort allowed his right arm to slip around and hook a finger into the reserve handle. As the reserve deployed it took a lot of pressure off his body, enabling him to move his arms and rip off the mask that threatened to suffocate him, allowing him to suck in great breaths of air. The reserve lazily tried to inflate but was hampered by the tangle of lift webs and rigging lines that entwined him. It certainly helped retard his rate of descent, but he was still falling too fast for comfort. The relief of pressure on his chest was a godsend, enabling him to start trying to free the rigging lines. Just as he was about to congratulate himself he saw the dark, menacing shape of pine trees coming up fast to meet him.

He crashed through the wooden canopy. The springy boughs slowed his fall, depositing him on mother earth with surprising gentleness, as if seeking forgiveness for the terror she had put him through. Lying there with the red handle welded to his sweaty palm, Ron looked skyward and offered his thanks.

Tony, with Fred a few yards behind, followed the edge of the wood, stopping often to listen, while Fred scanned the landscape with his night sight. At the apex of the wood where it joined a young plantation, Fred grabbed Tony’s arm and offered him the night sight, pointing ahead. Adjusting the scope slightly, Tony could make out the billowing canopy entangled high among the branches of a tall pine. Following the rigging lines down, he spotted a figure sprawled at the base of the tree.

Covering the short distance in record time, Tony prepared himself for the worst. He gently lifted the man’s head and recognised Ron in the slim beam of his wildly shaking pencil torch. Tony whispered his name. A large grin appeared on the face of the trooper, followed by a wink. Confused for a second, and still gently cradling the head, Tony was amazed when the corpse said, ‘Am I late, boss?’

At this, Tony lost control. ‘You f—ing great dozy bastard. What the f—ing hell do you think you’re doing?’ He ranted and raged, threatening to tear Ron a new rectum. Fred tried calming him down, but Tony had to run out of expletives first and get rid of all his pent-up emotion. The gentle cradling had turned into a neck choke as Tony tried to erase the stupid grin from Ron’s face.

Ron was happy with all the attention he was getting, offering no resistance to Tony’s onslaught. Nothing could be worse than what he had just experienced; he was simply glad to be alive. Finally Tony calmed down and released him.

‘Can I say something, Tony?’ Ron asked nervously. Tony nodded, breathing deeply to bring himself under control. ‘Can I have a troop transfer?’

Fred stepped in to avert another outburst but was surprised when Tony put a reassuring hand on Ron’s shoulder and said, ‘We’ll talk about it back in camp.’

In a clump of stunted mountain ash, Tony reported in to Flight Lt Mace, the DZ safety officer. He told him of the location of Trooper Ron Chandler and left him and the doctor to help recover his kit.