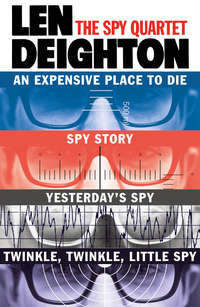

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

The old woman knocked discreetly and entered. ‘A car with Paris plates – it sounds like Madame Loiseau – coming through the village.’

Datt nodded. ‘Tell Robert I want the Belgian plates on the ambulance and the documents must be ready. Jean-Paul can help him. No, on second thoughts don’t tell Jean-Paul to help him. I believe they don’t get along too well.’ The old woman said nothing. ‘Yes, well that’s all.’

Datt walked across to the window and as he did so there was the sound of tyres crunching on the gravel.

‘It’s Maria’s car,’ said Datt.

‘And your backyard Mafia didn’t stop it?’

‘They are not there to stop people,’ explained Datt. ‘They are not collecting entrance money, they are there for my protection.’

‘Did Kuang tell you that?’ I said. ‘Perhaps those guards are there to stop you getting out.’

‘Poof,’ said Datt, but I knew I had planted a seed in his mind. ‘I wish she’d brought the boy with her.’

I said, ‘It’s Kuang who’s in charge. He didn’t ask you before agreeing to my bringing Hudson here.’

‘We have our areas of authority,’ said Datt. ‘Everything concerning data of a technical kind – of the kind that Hudson can provide – is Kuang’s province.’ Suddenly he flushed with anger. ‘Why should I explain such things to you?’

‘I thought you were explaining them to yourself,’ I said.

Datt changed the subject abruptly. ‘Do you think Maria told Loiseau where I am?’

‘I’m sure she didn’t,’ I said. ‘She has a lot of explaining to do the next time she sees Loiseau. She has to explain why she warned you about his raid on the clinic.’

‘That’s true,’ said Datt. ‘A clever man, Loiseau. At one time I thought you were his assistant.’

‘And now?’

‘Now I think you are his victim, or soon will be.’

I said nothing. Datt said, ‘Whoever you work for, you run alone. Loiseau has no reason to like you. He’s jealous of your success with Maria – she adores you, of course. Loiseau pretends he’s after me, but you are his real enemy. Loiseau is in trouble with his department, he might have decided that you could be the scapegoat. He visited me a couple of weeks ago, wanted me to sign a document concerning you. A tissue of lies, but cleverly riddled with half-truths that could prove bad for you. It needed only my signature. I refused.’

‘Why didn’t you sign?’

M. Datt sat down opposite me and looked me straight in the eye. ‘Not because I like you particularly. I hardly know you. It was because I had given you that injection when I first suspected that you were an agent provocateur sent by Loiseau. If I treat a person he becomes my patient. I become responsible for him. It is my proud boast that if one of my patients committed even a murder he could come to me and tell me; in confidence. That’s my relationship with Kuang. I must have that sort of relationship with my patients – Loiseau refuses to understand that. I must have it.’ He stood up suddenly and said, ‘A drink – and now I insist. What shall it be?’

The door opened and Maria came in, followed by Hudson and Jean-Paul. Maria was smiling, but her eyes were narrow and tense. Her old roll-neck pullover and riding breeches were stained with mud and wine. She looked tough and elegant and rich. She came into the room quietly and aware, like a cat sniffing, and moving stealthily, on the watch for the slightest sign of things hostile or alien. She handed me the packet of documents: three passports, one for me, one for Hudson, one for Kuang. There were some other papers inside, money and some cards and envelopes that would prove I was someone else. I put them in my pocket without looking at them.

‘I wish you’d brought the boy,’ said M. Datt to Maria. She didn’t answer. ‘What will you drink, my good friends? An aperitif perhaps?’ He called to the woman in the white apron, ‘We shall be seven to dinner but Mr Hudson and Mr Kuang will dine separately in the library. And take Mr Hudson into the library now,’ he added. ‘Mr Kuang is waiting there.’

‘And leave the door ajar,’ I said affably.

‘And leave the door ajar,’ said M. Datt.

Hudson smiled and gripped his briefcase tight under his arm. He looked at Maria and Jean-Paul, nodded and withdrew without answering. I got up and walked across to the window, wondering if the woman in the white apron was sitting in at dinner with us, but then I saw the dented tractor parked close behind Maria’s car. The tractor driver was here. With all that room to spare the tractor needn’t have boxed both cars tight against the wall.

30

‘Read the greatest thinkers of the eighteenth century,’ M. Datt was saying, ‘and you’ll understand what the Frenchman still thinks about women.’ The soup course was finished and the little woman – dressed now in a maid’s formal uniform – collected the dishes. ‘Don’t stack them,’ M. Datt whispered loudly to her. ‘That’s how they get broken. Make two journeys; a well-trained maid never stacks plates.’ He poured a glass of white wine for each of us. ‘Diderot thought they were merely courtesans, Montesquieu said they were pretty children. For Rousseau they existed only as an adjunct to man’s pleasure and for Voltaire they didn’t exist at all.’ He pulled the side of smoked salmon towards him and sharpened the long knife.

Jean-Paul smiled knowingly. He was more nervous than usual. He patted the white starched cuff that artfully revealed the Cartier watch and fingered the small disc of adhesive plaster that covered a razor nick on his chin.

Maria said, ‘France is a land where men command and women obey. “Elle me plait” is the greatest compliment a woman can expect from men; they mean she obeys. How can anyone call Paris a woman’s city? Only a prostitute can have a serious career there. It took two world wars to give Frenchwomen the vote.’

Datt nodded. He removed the bones and the salmon’s smoke-hard surface with two long sweeps of the knife. He brushed oil over the fish and began to slice it, serving Maria first. Maria smiled at him.

Just as an expensive suit wrinkles in a different way from a cheap one, so did the wrinkles in Maria’s face add to her beauty rather than detract from it. I stared at her, trying to understand her better. Was she treacherous, or was she exploited, or was she, like most of us, both?

‘It’s all very well for you, Maria,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘You are a woman with wealth, position, intelligence,’ he pause, ‘and beauty …’

‘I’m glad you added beauty,’ she said, still smiling.

Jean-Paul looked towards M. Datt and me. ‘That illustrates my point. Even Maria would sooner have beauty than brains. When I was eighteen – ten years ago – I wanted to give the women I loved the things I wanted for myself: respect, admiration, good food, conversation, wit and even knowledge. But women despise those things. Passion is what they want, intensity of emotion. The same trite words of admiration repeated over and over again. They don’t want good food – women have poor palates – and witty conversation worries them. What’s worse it diverts attention away from them. Women want men who are masterful enough to give them confidence, but not cunning enough to outwit them. They want men with plenty of faults so that they can forgive them. They want men who have trouble with the little things in life; women excel at little things. They remember little things too; there is no occasion in their lives, from confirmation to eightieth birthday, when they can’t recall every stitch they wore.’ He looked accusingly at Maria.

Maria laughed. ‘That part of your tirade at least is true.’

M. Datt said, ‘What did you wear at your confirmation?’

‘White silk, high-waisted dress, plain-front white silk shoes and cotton gloves that I hated.’ She reeled it off.

‘Very good,’ said M. Datt and laughed. ‘Although I must say, Jean-Paul, you are far too hard on women. Take that girl Annie who worked for me. Her academic standards were tremendous …’

‘Of course,’ said Maria, ‘women leaving university have such trouble getting a job that anyone enlightened enough to employ them is able to demand very high qualifications.’

‘Exactly,’ said M. Datt. ‘Most of the girls I’ve ever used in my research were brilliant. What’s more they were deeply involved in the research tasks. Just imagine that the situation had required men employees to involve themselves sexually with patients. In spite of paying lip-service to promiscuity men would have given me all sorts of puritanical reasons why they couldn’t do it. These girls understood that it was a vital part of their relationship with patients. One girl was a mathematical genius and yet such beauty. Truly remarkable.’

Jean-Paul said, ‘Where is this mathematical genius now? I would dearly appreciate her advice. Perhaps I could improve my technique with women.’

‘You couldn’t,’ said Maria. She spoke clinically, with no emotion showing. ‘Your technique is all too perfect. You flatter women to saturation point when you first meet them. Then, when you decide the time is right, you begin to undermine their confidence in themselves. You point out their shortcomings rather cleverly and sympathetically until they think that you must be the only man who would deign to be with them. You destroy women by erosion because you hate them.’

‘No,’ Jean-Paul said. ‘I love women. I love all women too much to reject so many by marrying one.’ He laughed.

‘Jean-Paul feels it is his duty to make himself available to every girl from fifteen to fifty,’ said Maria quietly.

‘Then you’ll soon be outside my range of activity,’ said Jean-Paul.

The candles had burned low and now their light came through the straw-coloured wine and shone golden on face and ceiling.

Maria sipped at her wine. No one spoke. She placed the glass on the table and then brought her eyes up to Jean-Paul’s. ‘I’m sorry for you, Jean-Paul,’ she said.

The maid brought the fish course to the table and served it: sole Dieppoise, the sauce dense with shrimps and speckled with parsley and mushroom, the bland smell of the fish echoed by the hot butter. The maid retired, conscious that her presence had interrupted the conversation. Maria drank a little more wine and as she put the glass down she looked at Jean-Paul.

He didn’t smile. When she spoke her voice was mellow and any trace of bitterness had been removed by the pause.

‘When I say I’m sorry for you, Jean-Paul, with your endless succession of lovers, you may laugh at me. But let me tell you this: the shortness of your relationships with women is due to a lack of flexibility in you. You are not able to adapt, change, improve, enjoy new things each day. Your demands are constant and growing narrower. Everyone else must adapt to you, never the other way about.

‘Marriages break up for this same reason – my marriage did and it was at least half my fault: two people become so set in their ways that they become vegetables. The antithesis of this feeling is to be in love. I fell in love with you, Jean-Paul. Being in love is to drink in new ideas, new feelings, smells, tastes, new dances – even the air seems to be different in flavour. That’s why infidelity is such a shock. A wife set in the dull, lifeless pattern of marriage is suddenly liberated by love, and her husband is terrified to see the change take place, for just as I felt ten years younger, so I saw my husband as ten years older.’

Jean-Paul said, ‘And that’s how you now see me?’

‘Exactly. It’s laughable how I once worried that you were younger than me. You’re not younger than me at all. You are an old fogey. Now I no longer love you I can see that. You are an old fogey of twenty-eight and I am a young girl of thiry-two.’

‘You bitch.’

‘My poor little one. Don’t be angry. Think of what I tell you. Open your mind. Open your mind and you will discover what you want so much: how to be eternally a young man.’

Jean-Paul looked at her. He wasn’t as angry as I would have expected. ‘Perhaps I am a shallow and vain fool,’ he said. ‘But when I met you, Maria, I truly loved you. It didn’t last more than a week, but for me it was real. It was the only time in my life that I truly believed myself capable of something worthwhile. You were older than me but I liked that. I wanted you to show me the way out of the stupid labyrinth life I led. You are highly intelligent and you, I thought, could show me the solid good reasons for living. But you failed me, Maria. Like all women you are weak-willed and indecisive. You can be loyal only for a moment to whoever is near to you. You have never made one objective decision in your life. You have never really wanted to be strong and free. You have never done one decisive thing that you truly believed in. You are a puppet, Maria, with many puppeteers, and they quarrel over who shall operate you.’ His final words were sharp and bitter and he stared hard at Datt.

‘Children,’ Datt admonished. ‘Just as we were all getting along so well together.’

Jean-Paul smiled a tight, film-star smile. ‘Turn off your charm,’ he said to Datt. ‘You always patronize me.’

‘If I’ve done something to give offence …’ said Datt. He didn’t finish the sentence but looked around at his guests, raising his eyebrows to show how difficult it was to even imagine such a possibility.

‘You think you can switch me on and off as you please,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘You think you can treat me like a child; well you can’t. Without me you would be in big trouble now. If I had not brought you the information about Loiseau’s raid upon your clinic you would be in prison now.’

‘Perhaps,’ said Datt, ‘and perhaps not.’

‘Oh I know what you want people to believe,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘I know you like people to think you are mixed up with the SDECE and secret departments of the Government, but we know better. I saved you. Twice. Once with Annie, once with Maria.’

‘Maria saved me,’ said Datt, ‘if anyone did.’

‘Your precious daughter,’ said Jean-Paul, ‘is good for only one thing.’ He smiled. ‘And what’s more she hates you. She said you were foul and evil; that’s how much she wanted to save you before I persuaded her to help.’

‘Did you say that about me?’ Datt asked Maria, and even as she was about to reply he held up his hand. ‘No, don’t answer. I have no right to ask you such a question. We all say things in anger that later we regret.’ He smiled at Jean-Paul. ‘Relax, my good friend, and have another glass of wine.’

Datt filled Jean-Paul’s glass but Jean-Paul didn’t pick it up. Datt pointed the neck of the bottle at it. ‘Drink.’ He picked up the glass and held it to Jean-Paul. ‘Drink and say that these black thoughts are not your truly considered opinion of old Datt who has done so much for you.’

Jean-Paul brought the flat of his hand round in an angry sweeping gesture. Perhaps he didn’t like to be told that he owed Datt anything. He sent the full glass flying across the room and swept the bottle out of Datt’s hands. It slid across the table, felling the glasses like ninepins and flooding the cold blond liquid across the linen and cutlery. Datt stood up, awkwardly dabbing at his waistcoat with a table napkin. Jean-Paul stood up too. The only sound was of the wine, still chug-chugging out of the bottle.

‘Salaud!’ said Datt. ‘You attack me in my own home! You casse-pieds! You insult me in front of my guests and assault me when I offer you wine!’ He dabbed at himself and threw the wet napkin across the table as a sign that the meal would not continue. The cutlery jangled mournfully. ‘You will learn,’ said Datt. ‘You will learn here and now.’

Jean-Paul finally understood the hornet’s nest he had aroused in Datt’s brain. His face was set and defiant, but you didn’t have to be an amateur psychologist to know that if he could set the clock back ten minutes he’d rewrite his script.

‘Don’t touch me,’ Jean-Paul said. ‘I have villainous friends just as you do, and my friends and I can destroy you, Datt. I know all about you, the girl Annie Couzins and why she had to be killed. There are a few things you don’t know about that story. There are a few more things that the police would like to know too. Touch me, you fat old swine, and you’ll die as surely as the girl did.’ He looked around at us all. His forehead was moist with exertion and anxiety. He managed a grim smile. ‘Just touch me, just you try …!’

Datt said nothing, nor did any one of us. Jean-Paul gabbled on until his steam ran out. ‘You need me,’ he finally said to Datt, but Datt didn’t need him any more and there was no one in the room who didn’t know it.

‘Robert!’ shouted Datt. I don’t know if Robert was standing in the sideboard or in a crack in the floor, but he certainly came in fast. Robert was the tractor driver who had slapped the one-eared dog. He was as tall and broad as Jean-Paul but there the resemblance ended: Robert was teak against Jean-Paul’s papier-mâché.

Right behind Robert was the woman in the white apron. Now that they were standing side by side you could see a family resemblance: Robert was clearly the woman’s son. He walked forward and stood before Datt like a man waiting to be given a medal. The old woman stood in the doorway with a 12-bore shotgun held steady in her fists. It was a battered old relic, the butt was scorched and stained and there was a patch of rust around the muzzle as though it had been propped in a puddle. It was just the sort of thing that might be kept around the hall of a country house for dealing with rats and rabbits: an ill-finished mass-production job without styling or finish. It wasn’t at all the sort of gun I’d want to be shot with. That’s why I remained very, very still.

Datt nodded towards me, and Robert moved in and brushed me lightly but efficiently. ‘Nothing,’ he said. Robert walked over to Jean-Paul. In Jean-Paul’s suit he found a 6.35 Mauser automatic. He sniffed it and opened it, spilled the bullets out into his hand and passed the gun, magazine and bullets to Datt. Datt handled them as though they were some kind of virus. He reluctantly dropped them into his pocket.

‘Take him away, Robert,’ said Datt. ‘He makes too much noise in here. I can’t bear people shouting.’ Robert nodded and turned upon Jean-Paul. He made a movement of his chin and a clicking noise of the sort that encourages horses. Jean-Paul buttoned his jacket carefully and walked to the door.

‘We’ll have the meat course now,’ Datt said to the woman.

She smiled with more deference than humour and withdrew backwards, muzzle last.

‘Take him out, Robert,’ repeated Datt.

‘Maybe you think you don’t,’ said Jean-Paul earnestly, ‘but you’ll find …’ His words were lost as Robert pulled him gently through the door and closed it.

‘What are you going to do to him?’ asked Maria.

‘Nothing, my dear,’ said Datt. ‘But he’s become more and more tiresome. He must be taught a lesson. We must frighten him, it’s for the good of all of us.’

‘You’re going to kill him,’ said Maria.

‘No, my dear.’ He stood near the fireplace, and smiled reassuringly.

‘You are, I can feel it in the atmosphere.’

Datt turned his back on us. He toyed with the clock on the mantelpiece. He found the key for it and began to wind it up. It was a noisy ratchet.

Maria turned to me. ‘Are they going to kill him?’ she asked.

‘I think they are,’ I said.

She went across to Datt and grabbed his arm. ‘You mustn’t,’ she said. ‘It’s too horrible. Please don’t. Please father, please don’t, if you love me.’ Datt put his arm around her paternally but said nothing.

‘He’s a wonderful person,’ Maria said. She was speaking of Jean-Paul. ‘He would never betray you. Tell him,’ she asked me, ‘he must not kill Jean-Paul.’

‘You mustn’t kill him,’ I said.

‘You must make it more convincing than that,’ said Datt. He patted Maria. ‘If our friend here can tell us a way to guarantee his silence, some other way, then perhaps I’ll agree.’

He waited but I said nothing. ‘Exactly,’ said Datt.

‘But I love him,’ said Maria.

‘That can make no difference,’ said Datt. ‘I’m not a plenipotentiary from God, I’ve got no halos or citations to distribute. He stands in the way – not of me but of what I believe in: he stands in the way because he is spiteful and stupid. I do believe, Maria, that even if it were you I’d still do the same.’

Maria stopped being a suppliant. She had that icy calm that women take on just before using their nails.

‘I love him,’ said Maria. That meant that he should never be punished for anything except infidelity. She looked at me. ‘It’s your fault for bringing me here.’

Datt heaved a sigh and left the room.

‘And your fault that he’s in danger,’ she said.

‘Okay,’ I said, ‘blame me if you want to. On my colour soul the stains don’t show.’

‘Can’t you stop them?’ she said.

‘No,’ I told her, ‘it’s not that sort of film.’

Her face contorted as though cigar smoke was getting in her eyes. It went squashy and she began to sob. She didn’t cry. She didn’t do that mascara-respecting display of grief that winkles tear-drops out of the eyes with the corner of a tiny lace handkerchief while watching the whole thing in a well-placed mirror. She sobbed and her face collapsed. The mouth sagged, and the flesh puckered and wrinkled like blow-torched paintwork. Ugly sight, and ugly sound.

‘He’ll die,’ she said in a strange little voice.

I don’t know what happened next. I don’t know whether Maria began to move before the sound of the shot or after. Just as I don’t know whether Jean-Paul had really lunged at Robert, as Robert later told us. But I was right behind Maria as she opened the door. A .45 is a big pistol. The first shot had hit the dresser, ripping a hole in the carpentry and smashing half a dozen plates. They were still falling as the second shot fired. I heard Datt shouting about his plates and saw Jean-Paul spinning drunkenly like an exhausted whipping top. He fell against the dresser, supporting himself on his hand, and stared at me pop-eyed with hate and grimacing with pain, his cheeks bulging as though he was looking for a place to vomit. He grabbed at his white shirt and tugged it out of his trousers. He wrenched it so hard that the buttons popped and pinged away across the room. He had a great bundle of shirt in his hand now and he stuffed it into his mouth like a conjurer doing a trick called ‘how to swallow my white shirt’. Or how to swallow my pink-dotted shirt. How to swallow my pink shirt, my red, and finally dark-red shirt. But he never did the trick. The cloth fell away from his mouth and his blood poured over his chin, painting his teeth pink and dribbling down his neck and ruining his shirt. He knelt upon the ground as if to pray but his face sank to the floor and he died without a word, his ear flat against the ground, as if listening for hoof-beats pursuing him to another world.

He was dead. It’s difficult to wound a man with a .45. You either miss them or blow them in half.

The legacy the dead leave us are life-size effigies that only slightly resemble their former owners. Jean-Paul’s bloody body only slightly resembled him: its thin lips pressed together and the small circular plaster just visible on the chin.

Robert was stupefied. He was staring at the gun in horror. I stepped over to him and grabbed the gun away from him. I said, ‘You should be ashamed,’ and Datt repeated that.

The door opened suddenly and Hudson and Kuang stepped into the kitchen. They looked down at the body of Jean-Paul. He was a mess of blood and guts. No one spoke, they were waiting for me. I remembered that I was the one holding the gun. ‘I’m taking Kuang and Hudson and I’m leaving,’ I said. Through the open door to the hall I could see into the library, its table covered with their scientific documents: photos, maps and withered plants with large labels on them.

‘Oh no you don’t,’ said Datt.

‘I have to return Hudson intact because that’s part of the deal. The information he’s given Kuang has to be got back to the Chinese Government or else it wasn’t much good delivering it. So I must take Kuang too.’

‘I think he’s right,’ said Kuang. ‘It makes sense, what he says.’