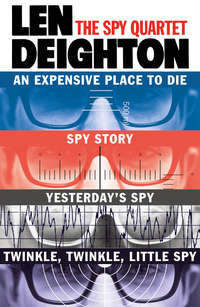

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘Joe’s all right,’ I said. ‘You leave him alone.’

‘Suit yourself,’ said Loiseau. ‘But if he gets much thinner he’ll be climbing out between the bars of that cage.’

I let him have the last word. He paid for the millet and walked between the cliffs of new empty cages, trying the bars and tapping the wooden panels. There were caged birds of all kinds in the market. They were given seed, millet, water and cuttlefish bone for their beaks. Their claws were kept trimmed and they were safe from all birds of prey. But it was the birds in the trees that were singing.

23

I got back to my apartment about twelve o’clock. At twelve thirty-five the phone rang. It was Monique, Annie’s neighbour. ‘You’d better come quickly,’ she said.

‘Why?’

‘I’m not allowed to say on the phone. There’s a fellow sitting here. He won’t tell me anything much. He was asking for Annie, he won’t tell me anything. Will you come now?’

‘Okay,’ I said.

24

It was lunchtime. Monique was wearing an ostrich-feather-trimmed négligé when she opened the door. ‘The English have got off the boat,’ she said and giggled. ‘You’d better come in, the old girl will be straining her earholes to hear, if we stand here talking.’ She opened the door and showed me into the cramped room. There was bamboo furniture and tables, a plastic-topped dressing-table with four swivel mirrors and lots of perfume and cosmetic garnishes. The bed was unmade and a candlewick bedspread had been rolled up under the pillows. A copy of Salut les Copains was in sections and arranged around the deep warm indentation. She went across to the windows and pushed the shutters. They opened with a loud clatter. The sunlight streamed into the room and made everything look dusty. On the table there was a piece of pink wrapping paper; she took a hard-boiled egg from it, rapped open the shell and bit into it.

‘I hate summer,’ she said. ‘Pimples and parks and open cars that make your hair tangled and rotten cold food that looks like left-overs. And the sun trying to make you feel guilty about being indoors. I like being indoors. I like being in bed; it’s no sin, is it, being in bed?’

‘Just give me the chance to find out. Where is he?’

‘I hate summer.’

‘So shake hands with Père Noël,’ I offered. ‘Where is he?’

‘I’m taking a shower. You sit down and wait. You are all questions.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Questions.’

‘I don’t know how you think of all these questions. You must be clever.’

‘I am,’ I said.

‘Honestly, I wouldn’t know where to start. The only questions I ever ask are “Are you married?” and “What will you do if I get pregnant?” Even then I never get told the truth.’

‘That’s the trouble with questions. You’d better stick to answers.’

‘Oh, I know all the answers.’

‘Then you must have been asked all the questions.’

‘I have,’ she agreed.

She slipped out of the négligé and stood naked for one millionth of a second before disappearing into the bathroom. The look in her eyes was mocking and not a little cruel.

There was a lot of splashing and ohh-ing from the bathroom until she finally reappeared in a cotton dress and canvas tennis shoes, no stockings.

‘Water was cold,’ she said briefly. She walked right through the room and opened her front door. I watched her lean over the balustrade.

‘The water’s stone cold, you stupid cow,’ she shrieked down the stair-well. From somewhere below the voice of the old harridan said, ‘It’s not supposed to supply ten people for each apartment, you filthy little whore.’

‘I have something men want, not like you, you old hag.’

‘And you give it to them,’ the harridan cackled back. ‘The more the merrier.’

‘Poof!’ shouted Monique, and narrowing her eyes and aiming carefully she spat over the stair-well. The harridan must have anticipated it, for I heard her cackle triumphantly.

Monique returned to me. ‘How am I expected to keep clean when the water is cold? Always cold.’

‘Did Annie complain about the water?’

‘Ceaselessly, but she didn’t have the manner that brings results. I get angry. If she doesn’t give me hot water I shall drive her into her grave, the dried-up old bitch. I’m leaving here anyway,’ she said.

‘Where are you going?’ I asked.

‘I’m moving in with my regular. Montmartre. It’s an awful district, but it’s larger than this, and anyway he wants me.’

‘What’s he do for a living?’

‘He does the clubs, he’s – don’t laugh – he’s a conjurer. It’s a clever trick he does: he takes a singing canary in a large cage and makes it disappear. It looks fantastic. Do you know how he does it?’

‘No.’

‘The cage folds up. That’s easy, it’s a trick cage. But the bird gets crushed. Then when he makes it reappear it’s just another canary that looks the same. It’s an easy trick really, it’s just that no one in the audience suspects that he would kill the bird each time in order to do the trick.’

‘But you guessed.’

‘Yes. I guessed the first time I saw it done. He thought I was clever to guess but as I said, “How much does a canary cost? Three francs, four at the very most.” It’s clever though, isn’t it, you’ve got to admit it’s clever.’

‘It’s clever,’ I said, ‘but I like canaries better than I like conjurers.’

‘Silly.’ Monique laughed disbelievingly. ‘“The incredible Count Szell” he calls himself.’

‘So you’ll be a countess?’

‘It’s his stage name, silly.’ She picked up a pot of face cream. ‘I’ll just be another stupid woman who lives with a married man.’

She rubbed cream into her face.

‘Where is he?’ I finally asked. ‘Where’s this fellow that you said was sitting here?’ I was prepared to hear that she’d invented the whole thing.

‘In the café on the corner. He’ll be all right there. He’s reading his American newspapers. He’s all right.’

‘I’ll go and talk to him.’

‘Wait for me.’ She wiped the cream away with a tissue and turned and smiled. ‘Am I all right?’

‘You’re all right,’ I told her.

25

The café was on the Boul. Mich., the very heart of the left bank. Outside in the bright sun sat the students; hirsute and earnest, they have come from Munich and Los Angeles sure that Hemingway and Lautrec are still alive and that some day in some left bank café they will find them. But all they ever find are other young men who look exactly like themselves, and it’s with this sad discovery that they finally return to Bavaria or California and become salesmen or executives. Meanwhile here they sat in the hot seat of culture, where businessmen became poets, poets became alcoholics, alcoholics became philosophers and philosophers realized how much better it was to be businessmen.

Hudson. I’ve got a good memory for faces. I saw Hudson as soon as we turned the corner. He was sitting alone at a café table holding his paper in front of his face while studying the patrons with interest. I called to him.

‘Jack Percival,’ I called. ‘What a great surprise.’

The American hydrogen research man looked surprised, but he played along very well for an amateur. We sat down with him. My back hurt from the rough-house in the discothèque. It took a long time to get served because the rear of the café was full of men with tightly wadded newspapers trying to pick themselves a winner instead of eating. Finally I got the waiter’s attention. ‘Three grands crèmes,’ I said. Hudson said nothing else until the coffees arrived.

‘What about this young lady?’ Hudson asked. He dropped sugar cubes into his coffee as though he was suffering from shock. ‘Can I talk?’

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘There are no secrets between Monique and me.’ I leaned across to her and lowered my voice. ‘This is very confidential, Monique,’ I said. She nodded and looked pleased. ‘There is a small plastic bead company with its offices in Grenoble. Some of the holders of ordinary shares have sold their holdings out to a company that this gentleman and I more or less control. Now at the next shareholders’ meeting we shall …’

‘Give over,’ said Monique. ‘I can’t stand business talk.’

‘Well run along then,’ I said, granting her her freedom with an understanding smile.

‘Could you buy me some cigarettes?’ she asked.

I got two packets from the waiter and wrapped a hundred-franc note round them. She trotted off down the street with them like a dog with a nice juicy bone.

‘It’s not about your bead factory,’ he said.

‘There is no bead factory,’ I explained.

‘Oh!’ He laughed nervously. ‘I was supposed to have contacted Annie Couzins,’ he said.

‘She’s dead.’

‘I found that out for myself.’

‘From Monique?’

‘You are T. Davis?’ he asked suddenly.

‘With bells on,’ I said and passed my resident’s card to him.

An untidy man with a constantly smiling face walked from table to table winding up toys and putting them on the tables. He put them down everywhere until each table had its twitching mechanical figures bouncing through the knives, table mats and ashtrays. Hudson picked up the convulsive little violin player. ‘What’s this for?’

‘It’s on sale,’ I said.

He nodded and put it down. ‘Everything is,’ he said.

He returned my resident’s card to me.

‘It looks all right,’ he agreed. ‘Anyway I can’t go back to the Embassy, they told me that most expressly, so I’ll have to put myself in your hands. I’m out of my depth to tell you the truth.’

‘Go ahead.’

‘I’m an authority on hydrogen bombs and I know quite a bit about all the work on the nuclear programme. My instructions are to put certain information about fall-out dangers at the disposal of a Monsieur Datt. I understand he is connected with the Red Chinese Government.’

‘And why are you to do this?’

‘I thought you’d know. It’s such a mess. That poor girl being dead. Such a tragedy. I did meet her once. So young, such a tragic business. I thought they would have told you all about it. You were the only other name they gave me, apart from her I mean. I’m acting on US Government orders, of course.’

‘Why would the US Government want you to give away fall-out data?’ I asked him. He sat back in the cane chair till it creaked like elderly arthritic joints. He pulled an ashtray near him.

‘It all began with the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests,’ he began. ‘The Atomic Energy Commission were taking a lot of criticism about the dangers of fall-out, the biological result upon wildlife and plants. The AEC needed those tests and did a lot of follow-through testing on the sites, trying to prove that the dangers were not anything like as great as many alarmists were saying. I have to tell you that those alarmists were damn nearly right. A dirty bomb of about twenty-five megatons would put down about 15,000 square miles of lethal radio-activity. To survive that, you would have to stay underground for months, some say even a year or more.

‘Now if we were involved in a war with Red China, and I dread the thought of such a thing, then we would have to use the nuclear fall-out as a weapon, because only ten per cent of the Chinese population live in large – quarter-million size – towns. In the USA more than half the population live in the large towns. China with its dispersed population can only be knocked out by fall-out …’ He paused. ‘But knocked out it can be. Our experts say that about half a billion people live on one-fifth of China’s land area. The prevailing wind is westerly. Four hundred bombs would kill fifty million by direct heat-blast effect, one hundred million would be seriously injured though they wouldn’t need hospitalization, but three hundred and fifty million would die by windborne fall-out.

‘The AEC minimized the fall-out effects in their follow-through reports on the tests (Bikini, etc.). Now the more militant of the Chinese soldier-scientists are using the US reports to prove that China can survive a nuclear war. We couldn’t withdraw those reports, or say that they were untrue – not even slightly untrue – so I’m here to leak the correct information to the Chinese scientists. The whole operation began nearly eight months ago. It took a long time getting this girl Annie Couzins into position.’

‘In the clinic near to Datt.’

‘Exactly. The original plan was that she should introduce me to this man Datt and say I was an American scientist with a conscience.’

‘That’s a piece of CIA thinking if ever I heard one?’

‘You think it’s an extinct species?’

‘It doesn’t matter what I think, but it’s not a line that Datt will buy easily.’

‘If you are going to start changing the plan now …’

‘The plan changed when the girl was killed. It’s a mess; the only way I can handle it is my way.’

‘Very well,’ said Hudson. He sat silent for a moment.

Behind me a man with a rucksack said, ‘Florence. We hated Florence.’

‘We hated Trieste,’ said a girl.

‘Yes,’ said the man with the rucksack, ‘my friend hated Trieste last year.’

‘My contact here doesn’t know why you are in Paris,’ I said suddenly. I tried to throw Hudson, but he took it calmly.

‘I hope he doesn’t,’ said Hudson. ‘It’s all supposed to be top secret. I hated to come to you about it but I’ve no other contact here.’

‘You’re at the Lotti Hotel.’

‘How did you know?’

‘It’s stamped across your Tribune in big blue letters.’

He nodded. I said, ‘You’ll go to the Hotel Ministère right away. Don’t get your baggage from the Lotti. Buy a toothbrush or whatever you want on the way back now.’ I expected to encounter opposition to this idea but Hudson welcomed the game.

‘I get you,’ he said. ‘What name shall I use?’

‘Let’s make it Potter,’ I said. He nodded. ‘Be ready to move out at a moment’s notice. And Hudson, don’t telephone or write any letters; you know what I mean. Because I could become awfully suspicious of you.’

‘Yes,’ he said.

‘I’ll put you in a cab,’ I said, getting up to leave.

‘Do that, their Métro drives me crazy.’

I walked up the street with him towards the cab-rank. Suddenly he dived into an optician’s. I followed.

‘Ask him if I can look at some spectacles,’ he said.

‘Show him some spectacles,’ I told the optician. He put a case full of tortoiseshell frames on the counter.

‘He’ll need a test,’ said the optician. ‘Unless he has his prescription he’ll need a test.’

‘You’ll need a test or a prescription,’ I told Hudson.

He had sorted out a frame he liked. ‘Plain glass,’ he demanded.

‘What would I keep plain glass around for?’ said the optician.

‘What would he keep plain glass for?’ I said to Hudson.

‘The weakest possible, then,’ said Hudson.

‘The weakest possible,’ I said to the optician. He fixed the lenses in in a moment or so. Hudson put the glasses on and we resumed our walk towards the taxi. He peered around him myopically and was a little unsteady.

‘Disguise,’ said Hudson.

‘I thought perhaps it was,’ I said.

‘I would have made a good spy,’ said Hudson. ‘I’ve often thought that.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Well, there’s your cab. I’ll be in touch. Check out of the Lotti into the Ministère. I’ve written the name down on my card, they know me there. Try not to attract attention. Stay inside.’

‘Where’s the cab?’ said Hudson.

‘If you’ll take off those bloody glasses,’ I said, ‘you might be able to see.’

26

I went round to Maria’s in a hurry. When she opened the door she was wearing riding breeches and a roll-neck pullover. ‘I was about to go out,’ she said.

‘I need to see Datt,’ I said.

‘Why do you tell me that?’

I pushed past her and closed the door behind us. ‘Where is he?’

She gave me a twitchy little ironical smile while she thought of something crushing to say. I grabbed her arm and let my fingertips bite. ‘Don’t fool with me, Maria. I’m not in the mood. Believe me I would hit you.’

‘I’ve no doubt about it.’

‘You told Datt about Loiseau’s raid on the place in the Avenue Foch. You have no loyalties, no allegiance, none to the Sûreté, none to Loiseau. You just give away information as though it was toys out of a bran tub.’

‘I thought you were going to say I gave it away as I did my sexual favours,’ she smiled again.

‘Perhaps I was.’

‘Did you remember that I kept your secret without giving it away? No one knows what you truly said when Datt gave you the injection.’

‘No one knows yet. I suspect that you are saving it up for something special.’

She swung her hand at me but I moved out of range. She stood for a moment, her face twitching with fury.

‘You ungrateful bastard,’ she said. ‘You’re the first real bastard I’ve ever met.’

I nodded. ‘There’s not many of us around. Ungrateful for what?’ I asked her. ‘Ungrateful for your loyalty? Was that what your motive was: loyalty?’

‘Perhaps you’re right,’ she admitted quietly. ‘I have no loyalty to anyone. A woman on her own becomes awfully hard. Datt is the only one who understands that. Somehow I didn’t want Loiseau to arrest him.’ She looked up. For that and many reasons.’

‘Tell me one of the other reasons.’

‘Datt is a senior man in the SDECE, and that’s one reason. If Loiseau clashed with him, Loiseau could only lose.’

‘Why do you think Datt is an SDECE man?’

‘Many people know. Loiseau won’t believe it but it’s true.’

‘Loiseau won’t believe it because he has got too much sense. I’ve checked up on Datt. He’s never had anything to do with any French intelligence unit. But he knew how useful it was to let people think so.’

She shrugged. ‘I know it’s true,’ she said. ‘Datt works for the SDECE.’

I took her shoulders. ‘Look, Maria. Can’t you get it through your head that he’s a phoney? He has no psychiatry diploma, has never been anything to do with the French Government except that he pulls strings among his friends and persuades even people like you who work for the Sûreté that he’s a highly placed agent of SDEGE.’

‘And what do you want?’ she asked.

‘I want you to help me find Datt.’

‘Help,’ she said. ‘That’s a new attitude. You come bursting in here making your demands. If you’d come in here asking for help I might have been more sympathetic. What is it you want with Datt?’

‘I want Kuang; he killed the girl at the clinic that day. I want to find him.’

‘It’s not your job to find him.’

‘You are right. It’s Loiseau’s job, but he is holding Byrd for it and he’ll keep on holding him.’

‘Loiseau wouldn’t hold an innocent man. Poof, you don’t know what a fuss he makes about the sanctity of the law and that sort of thing.’

‘I am a British agent,’ I said. ‘You know that already so I’m not telling you anything new. Byrd is too.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘No, I’m not. I’d be the last person to be told anyway. He’s not someone whom I would contact officially. It’s just my guess. I think Loiseau has been instructed to hold Byrd for the murder – with or without evidence – so Byrd is doomed unless I push Kuang right into Loiseau’s arms.’

Maria nodded.

‘Your mother lives in Flanders. Datt will be at his house near by, right?’ Maria nodded. ‘I want you to take an American out to your mother’s house and wait there till I phone.’

‘She hasn’t got a phone.’

‘Now, now, Maria,’ I said. ‘I checked up on your mother: she has a phone. Also I phoned my people here in Paris. They will be bringing some papers to your mother’s house. They’ll be needed for crossing the border. No matter what I say don’t come over to Datt’s without them.’

Maria nodded. ‘I’ll help. I’ll help you pin that awful Kuang. I hate him.’

‘And Datt, do you hate him too?’

She looked at me searchingly. ‘Sometimes, but in a different way,’ she said. ‘You see, I’m his illegitimate daughter. Perhaps you checked up on that too?’

27

The road was straight. It cared nothing for geography, geology or history. The oil-slicked highway dared children and divided neighbours. It speared small villages through their hearts and laid them open. It was logical that it should be so straight, and yet it was obsessive too. Carefully lettered signs – the names of villages and the times of Holy Mass – and then the dusty clutter of houses flicked past with seldom any sign of life. At Le Chateau I turned off the main road and picked my way through the small country roads. I saw the sign Plaisir ahead and slowed. This was the place I wanted.

The main street of the village was like something out of Zane Grey, heavy with the dust of passing vehicles. None of them stopped. The street was wide enough for four lanes of cars, but there was very little traffic. Plaisir was on the main road to nowhere. Perhaps a traveller who had taken the wrong road at St Quentin might pass through Plaisir trying to get back on the Paris-Brussels road. Some years back when they were building the autoroute, heavy lorries had passed through, but none of them had stopped at Plaisir.

Today it was hot; scorching hot. Four mangy dogs had scavenged enough food and now were asleep in the centre of the roadway. Every house was shuttered tight, grey and dusty in the cruel biting midday light that gave them only a narrow rim of shadow.

I stopped the car near to a petrol pump, an ancient, handle-operated instrument bolted uncertainly on to a concrete pillar. I got out and thumped upon the garage doors, but there was no response. The only other vehicle in sight was an old tractor parked a few yards ahead. On the other side of the street a horse stood, tethered to a piece of rusty farm machinery, flicking its tail against the flies. I touched the engine of the tractor: it was still warm. I hammered the garage doors again, but the only movement was the horse’s tail. I walked down the silent street, the stones hot against my shoes. One of the dogs, its left ear missing, scratched itself awake and crawled into the shade of the tractor. It growled dutifully at me as I passed, then subsided into sleep. A cat’s eyes peered through a window full of aspidistra plants. Above the window, faintly discernible in the weathered woodwork, I read the word ‘café’. The door was stiff and opened noisily. I went in.

There were half a dozen people standing at the bar. They weren’t talking and I had the feeling that they had been watching me since I left the car. They stared at me.

‘A red wine,’ I said. The old woman behind the bar looked at me without blinking. She didn’t move.

‘And a cheese sandwich,’ I added. She gave it another minute before slowly reaching for a wine bottle, rinsing a glass and pouring me a drink, all without moving her feet. I turned around to face the room. The men were mostly farm workers, their boots heavy with soil and their faces engraved with ancient dirt. In the corner a table was occupied by three men in suits and white shirts. Although it was long past lunchtime they had napkins tucked into their collars and were putting forkfuls of cheese into their mouths, honing their knives across the bread chunks and pouring draughts of red wine into their throats after it. They continued to eat. They were the only people in the room not looking at me except for a muscular man seated at the back of the room, his feet propped upon a chair, placing the cards of his patience game with quiet confidence. I watched him peel each card loose from the pack, stare at it with the superior impartiality of a computer and place it face up on the marble table-top. I watched him play for a minute or so, but he didn’t look up.

It was a dark room; the only light entering it filtered through the jungle of plants in the window. On the marble-topped tables there were drip-mats advertising aperitifs; the mats had been used many times. The bar was brown with varnish and above the rows of bottles was an old clock that had ticked its last at 3.37 on some long-forgotten day. There were old calendars on the walls, a broken chair had been piled neatly under the window and the floor-boards squealed with each change of weight. In spite of the heat of the day three men had drawn their chairs close to a dead stove in the centre of the room. The body of the stove had cracked, and from it cold ash had spilled on to the floor. One of the men tapped his pipe against the stove. More ash poured out like the sands of time.