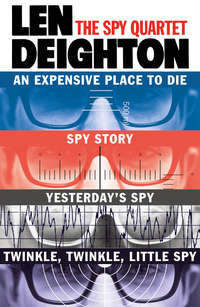

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘A desire,’ said M. Datt’s voice, ‘to externalize, to confide.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed.

‘I’ll bring him up with the Megimide if he goes too far,’ said M. Datt. ‘He’s fine like that. Fine response. Fine response.’

Maria repeated everything I said, as though Datt could not hear it himself. She said each thing not once but twice. I said it, then she said it, then she said it again differently; sometimes very differently so that I corrected her, but she was indifferent to my corrections and spoke in that fine voice she had; a round reed-clear voice full of song and sorrow like an oboe at night.

Now and again there was the voice of Datt deep and distant, perhaps from the next room. They seemed to think and speak so slowly. I answered Maria leisurely but it was ages before the next question came. I tired of the long pauses eventually. I filled the gaps telling them anecdotes and interesting stuff I’d read. I felt I’d known Maria for years and I remember saying ‘transference’, and Maria said it too, and Datt seemed very pleased. I found it was quite easy to compose my answers in poetry – not all of it rhymed, mind you – but I phrased it carefully. I could squeeze those damned words like putty and hand them to Maria, but sometimes she dropped them on to the marble floor. They fell noiselessly, but the shadows of them reverberated around the distant walls and furniture. I laughed again, and wondered whose bare arm I was staring at. Mind you, that wrist was mine, I recognized the watch. Who’d torn that shirt? Maria kept saying something over and over, a question perhaps. Damned shirt cost me £3.10s and now they’d torn it. The torn fabric was exquisite, detailed and jewel-like. Datt’s voice said, ‘He’s going now: it’s very short duration, that’s the trouble with it.’

Maria said, ‘Something about a shirt, I can’t understand, it’s so fast.’

‘No matter,’ said Datt. ‘You’ve done a good job. Thank God you were here.’

I wondered why they were speaking in a foreign language. I had told them everything. I had betrayed my employers, my country, my department. They had opened me like a cheap watch, prodded the main spring and laughed at its simple construction. I had failed and failure closed over me like a darkroom blind coming down.

Dark. Maria’s voice said, ‘He’s gone,’ and I went, a white seagull gliding through black sky, while beneath me the even darker sea was welcoming and still. And deep, and deep and deep.

9

Maria looked down at the Englishman. He was contorted and twitching, a pathetic sight. She felt inclined to cuddle him close. So it was as easy as that to discover a man’s most secret thoughts – a chemical reaction – extraordinary. He’d laid his soul bare to her under the influence of the Amytal and LSD, and now, in some odd way, she felt responsible – guilty almost – about his well-being. He shivered and she pulled the coat over him and tucked it around his neck. Looking around the damp walls of the dungeon she was in, she shivered too. She produced a compact and made basic changes to her make-up: the dramatic eye-shadow that suited last night would look terrible in the cold light of dawn. Like a cat, licking and washing in moments of anguish or distress. She removed all the make-up with a ball of cotton-wool, erasing the green eyes and deep red lips. She looked at herself and pulled that pursed face that she did only when she looked in a mirror. She looked awful without make-up, like a Dutch peasant; her jaw was beginning to go. She followed the jawbone with her finger, seeking out that tiny niche halfway along the line of it. That’s where the face goes, that niche becomes a gap and suddenly the chin and the jawbone separate and you have the face of an old woman.

She applied the moisture cream, the lightest of powder and the most natural of lipstick colours. The Englishman stirred and shivered; this time the shiver moved his whole body. He would become conscious soon. She hurried with her make-up, he mustn’t see her like this. She felt a strange physical thing about the Englishman. Had she spent over thirty years not understanding what physical attraction was? She had always thought that beauty and physical attraction were the same thing, but now she was unsure. This man was heavy and not young – late thirties, she’d guess – and his body was thick and uncared for. Jean-Paul was the epitome of masculine beauty: young, slim, careful about his weight and his hips, artfully tanned – all over, she remembered – particular about his hairdresser, ostentatious with his gold wristwatch and fine rings, his linen, precise and starched and white, like his smile.

Look at the Englishman: ill-fitting clothes rumpled and torn, plump face, hair moth-eaten, skin pale; look at that leather wristwatch strap and his terrible old-fashioned shoes – so English. Lace-up shoes. She remembered the lace-up shoes she had as a child. She hated them, it was the first manifestation of her claustrophobia, her hatred of those shoes. Although she hadn’t recognized it as such. Her mother tied the laces in knots, tight and restrictive. Maria had been extra careful with her son, he never wore laced shoes. Oh God, the Englishman was shaking like an epileptic now. She held his arms and smelled the ether and the sweat as she came close to him.

He would come awake quickly and completely. Men always did, they could snap awake and be speaking on the phone as though they had been up for hours. Man the hunter, she supposed, alert for danger; but they made no allowances. So many terrible rows with men began because she came awake slowly. The weight of his body excited her, she let it fall against her so that she took the weight of it. He’s a big ugly man, she thought. She said ‘ugly’ again and that word attracted her, so did ‘big’ and so did ‘man’. She said ‘big ugly man’ aloud.

I awoke but the nightmare continued. I was in the sort of dungeon that Walt Disney dreams up, and the woman was there saying ‘Big ugly man’ over and over. Thanks a lot, I thought, flattery will get you nowhere. I was shivering, and I came awake carefully; the woman was hugging me close, I must have been cold because I could feel the warmth of her. I’ll settle for this, I thought, but if the girl starts to fade I’ll close my eyes again, I need a dream.

It was a dungeon, that was the crazy thing. ‘It really is a dungeon,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ said Maria, ‘it is.’

‘What are you doing here then?’ I said. I could accept the idea of me being in a dungeon.

‘I’m taking you back,’ she said. ‘I tried to lift you out to the car but you were too heavy. How heavy are you?’

‘Never mind how heavy I am,’ I said. ‘What’s been going on?’

‘Datt was questioning you,’ she said. ‘We can leave now.’

‘I’ll show you who’s leaving,’ I said, deciding to seek out Datt and finish off the ashtray exercise. I jumped off the hard bench to push open the heavy door of the dungeon. It was as though I was descending a non-existent staircase and by the time I reached the door I was on the wet ground, my legs twitching uselessly and unable to bear my weight.

‘I didn’t think you’d get even this far,’ said Maria, coming across to me. I took her arm gratefully and helped myself upright by clawing at the door fixtures. Step by difficult step we inched through the cellar, past the rack, pincers and thumbscrews and the cold fireplace with the branding irons scattered around it. ‘Who lives here?’ I asked. ‘Frankenstein?’

‘Hush,’ said Maria. ‘Keep your strength for walking.’

‘I had a terrible dream,’ I said. It had been a dream of terrible betrayal and impending doom.

‘I know,’ said Maria. ‘Don’t think about it.’

The dawn sky was pale as though the leeches of my night had grown fat upon its blood. ‘Dawns should be red,’ I said to Maria.

‘You don’t look so good yourself,’ she said, and helped me into the car.

She drove a couple of blocks from the house and parked under the trees amid the dead motor cars that litter the city. She switched the heater on and the warm air suffused my limbs.

‘Do you live alone?’ she asked.

‘What’s that, a proposal?’

‘You aren’t fit enough to be left alone.’

‘Agreed,’ I said. I couldn’t shake off the coma of fear and Maria’s voice came to me as I had heard it in the nightmare.

‘I’ll take you to my place, it’s not far away,’ she said.

‘That’s okay,’ I said. ‘I’m sure its worth a detour.’

‘It’s worth a journey. Three-star food and drink,’ she said. ‘How about a croque monsieur and a baby?’5

‘The croque monsieur would be welcome,’ I agreed.

‘But having the baby together might well be the best part,’ she said.

She didn’t smile, she kicked the accelerator and the power surged through the car like the blood through my reviving limbs. She watched the road, flashing the lights at each intersection and flipping the needle around the clock at the clear stretches. She loved the car, caressing the wheel and agog with admiration for it; and like a clever lover she coaxed it into effortless perfomance. She came down the Champs for speed and along the north side of the Seine before cutting up through Les Halles. The last of the smart set had abandoned their onion soup and now the lorries were being unloaded. The fortes were working like looters, stacking the crates of vegetables and boxes of fish. The lorry-drivers had left their cabs to patronize the brothels that crowd the streets around the Square des Innocents. Tiny yellow doorways were full of painted whores and arguing men in bleu de travail. Maria drove carefully through the narrow streets.

‘You’ve seen this district before?’ she asked.

‘No,’ I said, because I had a feeling that she wanted me to say that. I had a feeling that she got some strange titillation from bringing me this way to her home. ‘Ten new francs,’ she said, nodding towards two girls standing outside a dingy café. ‘Perhaps seven if you argued.’

‘The two?’

‘Maybe twelve if you wanted the two. More for an exhibition.’

She turned to me. ‘You are shocked.’

‘I’m only shocked that you want me to be shocked,’ I said.

She bit her lip and turned on to the Sebastopol and speeded out of the district. It was three minutes before she spoke again. ‘You are good for me,’ she said.

I wasn’t sure she was right but I didn’t argue.

That early in the morning the street in which Maria lived was little different from any other street in Paris; the shutters were slammed tight and not a glint of glass or ruffle of curtain was visible anywhere. The walls were colourless and expressionless as though every house in the street was mourning a family death. The ancient crumbling streets of Paris were distinguished socially only by the motor cars parked along the gutters. Here the R4s, corrugated deux chevaux and dented Dauphines were outnumbered by shiny new Jags, Buicks and Mercs.

Inside, the carpets were deep, the hangings lush, the fittings shiny and the chairs soft. And there was that symbol of status and influence: a phone. I bathed in hot perfumed water and sipped aromatic broth, I was tucked into crisp sheets, my memories faded and I slept a long dreamless sleep.

When I awoke the radio was playing Françoise Hardy in the next room and Maria was sitting on the bed. She looked at me as I stirred. She had changed into a pink cotton dress and was wearing little or no make-up. Her hair was loose and combed to a simple parting in that messy way that takes a couple of hours of hairdressing expertise. Her face was kind but had the sort of wrinkles that come when you have smiled cynically about ten million times. Her mouth was small and slightly open like a doll, or like a woman expecting a kiss.

‘What time is it?’ I asked.

‘It’s past midnight,’ she said. ‘You’ve slept the clock round.’

‘Get this bed on the road. What’s wrong, have we run out of feathers?’

‘We ran out of bedclothes; they are all around you.’

‘Fill her up with bedclothes mister and if we forget to check the electric blanket you get a bolster free.’

‘I’m busy making coffee. I’ve no time to play your games.’

She made coffee and brought it. She waited for me to ask questions and then she answered deftly, telling me as much as she wished without seeming evasive.

‘I had a nightmare and awoke in a medieval dungeon.’

‘You did,’ said Maria.

‘You’d better tell me all about it,’ I said.

‘Datt was terrified that you were spying on him. He said you have documents he wants. He said you had been making inquiries so he had to know.’

‘What did he do to me?’

‘He injected you with Amytal and LSD (it’s the LSD that takes time to wear off). I questioned you. Then you went into a deep sleep and awoke in the cellars of the house. I brought you here.’

‘What did I say?’

‘Don’t worry. None of those people speak English. I’m the only one that does. Your secrets are safe with me. Datt usually thinks of everything, but he was disconcerted when you babbled away in English. I translated.’

So that was why I’d heard her say everything twice. ‘What did I say?’

‘Relax. It didn’t interest me but I satisfied Datt.’

I said, ‘And don’t think I don’t appreciate it, but why should you do that for me?’

‘Datt is a hateful man. I would never help him, and anyway, I took you to that house, I felt responsible for you.’

‘And …?’

‘If I had told him what you really said he would have undoubtedly used amphetamine on you, to discover more and more. Amphetamine is dangerous stuff, horrible. I wouldn’t have enjoyed watching that.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. I reached towards her, took her hand, and she lay down on the bed at my side. She did it without suspicion or arch looks, it was a friendly, rather than a sexual gesture. She lit a cigarette and gave me the packet and matches. ‘Light it yourself,’ she said. ‘It will give you something to do with your hands.’

‘What did I say?’ I asked casually. ‘What did I say that you didn’t translate into French for Datt?’

‘Nothing,’ Maria said immediately. ‘Not because you said nothing, but because I didn’t hear it. Understand? I’m not interested in what you are or how you earn your living. If you are doing something that’s illegal or dangerous, that’s your worry. Just for the moment I feel a little responsible for you, but I’ve nearly worked off that feeling. Tomorrow you can start telling your own lies and I’m sure you will do it remarkably well.’

‘Is that a brush-off?’

She turned to me. ‘No,’ she said. She leaned over and kissed me.

‘You smell delicious,’ I said. ‘What is it you’re wearing?’

‘Agony,’ she said. ‘It’s an expensive perfume, but there are few humans not attracted to it.’

I tried to decide whether she was geeing me up, but I couldn’t tell. She wasn’t the sort of girl who’d help you by smiling, either.

She got off the bed and smoothed her dress over her hips.

‘Do you like this dress?’ she asked.

‘It’s great,’ I said.

‘What sort of clothes do you like to see women in?’

‘Aprons,’ I said. ‘Fingers a-shine with those marks you get from handling hot dishes.’

‘Yes, I can imagine,’ she said. She stubbed out her cigarette.

‘I’ll help you if you want help but don’t ask too much, and remember that I am involved with these people and I have only one passport and it’s French.’

I wondered if that was a hint about what I’d revealed under the drugs, but I said nothing.

She looked at her wristwatch. ‘It’s very late,’ she said. She looked at me quizzically. ‘There’s only one bed and I need my sleep.’ I had been thinking of having a cigarette but I replaced them on the side table. I moved aside. ‘Share the bed,’ I invited, ‘but I can’t guarantee sleep.’

‘Don’t pull the Jean-Paul lover-boy stuff,’ she said, ‘it’s not your style.’ She grabbed at the cotton dress and pulled it over her head.

‘What is my style?’ I asked irritably.

‘Check with me in the morning,’ she said, and put the light out. She left only the radio on.

10

I stayed in Maria’s flat but the next afternoon Maria went back to my rooms to feed Joe. She got back before the storm. She came in blowing on her hands and complaining of the cold.

‘Did you change the water and put the cuttlefish bone in?’ I asked.

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘It’s good for his beak,’ I said.

‘I know,’ she said. She stood by the window looking out over the fast-darkening boulevard. ‘It’s primitive,’ she said without turning away from the window. ‘The sky gets dark and the wind begins to lift hats and boxes and finally dustbin lids, and you start to think this is the way the world will end.’

‘I think politicians have other plans for ending the world,’ I said.

‘The rain is beginning. Huge spots, like rain for giants. Imagine being an ant hit by a …’

The phone rang. ‘ … raindrop like that.’ Maria finished the sentence hurriedly and picked up the phone.

She picked it up as though it was a gun that might explode by accident. ‘Yes,’ she said suspiciously. ‘He’s here.’ She listened, nodding, and saying ‘yes’. ‘The walk will do him good,’ she said. ‘We’ll be there in about an hour.’ She pulled an agonized face at me. ‘Yes,’ she said to the phone again. ‘Well you must just whisper to him and then I won’t hear your little secrets, will I?’ There was a little gabble of electronic indignation, then Maria said, ‘We’ll get ready now or we’ll be late,’ and firmly replaced the receiver. ‘Byrd,’ she said. ‘Your countryman Mr Martin Langley Byrd craves a word with you at the Café Blanc.’ The noise of rain was like a vast crowd applauding frantically.

‘Byrd,’ I explained, ‘is the man who was with me at the art gallery. The art people think a lot of him.’

‘So he was telling me,’ said Maria.

‘Oh, he’s all right,’ I said. ‘An ex-naval officer who becomes a bohemian is bound to be a little odd.’

‘Jean-Paul likes him,’ said Maria, as though it was the epitome of accolades. I climbed into my newly washed underwear and wrinkled suit. Maria discovered a tiny mauve razor and I shaved millimetre by millimetre and swamped the cuts with cologne. We left Maria’s just as the rain shower ended. The concierge was picking up the potted plants that had been standing on the pavement.

‘You are not taking a raincoat?’ she asked Maria.

‘No,’ said Maria.

‘Perhaps you’ll only be out for a few minutes,’ said the concierge. She pushed her glasses against the bridge of her nose and peered at me.

‘Perhaps,’ said Maria, and took my arm to walk away.

‘It will rain again,’ called the concierge.

‘Yes,’ said Maria.

‘Heavily,’ called the concierge. She picked up another pot and prodded the earth in it.

Summer rain is cleaner than winter rain. Winter rain strikes hard upon the granite, but summer rain is sibilant soft upon the leaves. This rainstorm pounced hastily like an inexperienced lover, and then as suddenly was gone. The leaves drooped wistfully and the air gleamed with green reflections. It’s easy to forgive the summer rain; like first love, white lies or blarney, there’s no malignity in it.

Byrd and Jean-Paul were already seated at the café. Jean-Paul was as immaculate as a shop-window dummy but Byrd was excited and dishevelled. His hair was awry and his eyebrows almost non-existent, as though he’d been too near a water-heater blow-back. They had chosen a seat near the side screens and Byrd was wagging a finger and talking excitedly. Jean-Paul waved to us and folded his ear with his fingers. Maria laughed. Byrd was wondering if Jean-Paul was making a joke against him, but deciding he wasn’t, continued to speak.

‘Simplicity annoys them,’ Byrd said. ‘It’s just a rectangle, one of them complained, as though that was a criterion of art. Success annoys them. Even though I make almost no money out of my painting, that doesn’t prevent the critics who feel my work is bad from treating it like an indecent assault, as though I have deliberately chosen to do bad work in order to be obnoxious. They have no kindness, no compassion, you see, that’s why they call them critics – originally the word meant a captious fool; if they had compassion they would show it.’

‘How?’ asked Maria.

‘By painting. That’s what a painting is, a statement of love. Art is love, stricture is hate. It’s obvious, surely. You see, a critic is a man who admires painters (he wants to be one) but cares little for paintings (which is why he isn’t one). A painter, on the other hand, admires paintings, but doesn’t like painters.’ Byrd, having settled that problem, waved to a waiter. ‘Four grands crèmes and some matches,’ he ordered.

‘I want black coffee,’ said Maria.

‘I prefer black too,’ said Jean-Paul.

Byrd looked at me and made a little noise with his lips. ‘You want black coffee?’

‘White will suit me,’ I said. He nodded an appreciation of a fellow countryman’s loyalty. ‘Two crèmes – grands crèmes – and two small blacks,’ he ordered. The waiter arranged the beer mats, picked up some ancient checks and tore them in half. When he had gone Byrd leaned towards me. ‘I’m glad,’ he said – he looked around to see that the other two did not hear. They were talking to each other – ‘I’m glad you drink white coffee. It’s not good for the nerves, too much of this very strong stuff.’ He lowered his voice still more. ‘That’s why they are all so argumentative,’ he said in a whisper. When the coffees came Byrd arranged them on the table, apportioned the sugar, then took the check.

‘Let me pay,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘It was my invitation.’

‘Not on your life,’ said Byrd. ‘Leave this to me, Jean-Paul. I know how to handle this sort of thing, it’s my part of the ship.’

Maria and I looked at each other without expression. Jean-Paul was watching closely to discover our relationship.

Byrd relished the snobbery of certain French phrases. Whenever he changed from speaking French into English I knew it was solely because he intended to introduce a long slab of French into his speech and give a knowing nod and slant his face significantly, as if we two were the only people in the world who understood the French language.

‘Your inquiries about this house,’ said Byrd. He raised his forefinger. ‘Jean-Paul has remarkable news.’

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘Seems, my dear fellow, that there’s something of a mystery about your friend Datt and that house.’

‘He’s not a friend of mine,’ I said.

‘Quite quite,’ said Byrd testily. ‘The damned place is a brothel, what’s more …’

‘It’s not a brothel,’ said Jean-Paul as though he had explained this before. ‘It’s a maison de passe. It’s a house that people go to when they already have a girl with them.’

‘Orgies,’ said Byrd. ‘They have orgies there. Frightful goings on Jean-Paul tells me, drugs called LSD, pornographic films, sexual displays …’

Jean-Paul took over the narrative. ‘There are facilities for every manner of perversion. They have hidden cameras there and even a great mock torture-chamber where they put on shows …’

‘For masochists,’ said Byrd. ‘Chaps who are abnormal, you see.’

‘Of course he sees,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘Anyone who lives in Paris knows how widespread are such parties and exhibitions.’

‘I didn’t know,’ said Byrd. Jean-Paul said nothing. Maria offered her cigarettes around and said to Jean-Paul, ‘Where did Pierre’s horse come in yesterday?’

‘A friend of theirs with a horse,’ Byrd said to me.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Nowhere,’ said Jean-Paul.

‘Then I lost my hundred nouveaux,’ said Maria.

‘Foolish,’ said Byrd to me. He nodded.

‘My fault,’ said Jean-Paul.

‘That’s right,’ said Maria. ‘I didn’t give it a second look until you said it was a certainty.’

Byrd gave another of his conspiratorial glances over the shoulder.

‘You,’ he pointed to me as though he had just met me on a footpath in the jungle, ‘work for the German magazine Stern.’