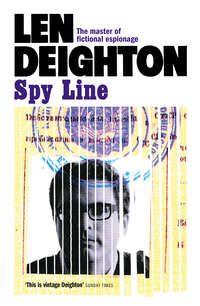

Spy Line

‘Is Johnny all right?’

‘Johnny is at the Polizeipräsidium answering questions. They’re holding him.’

‘He has no papers,’ I said.

‘Right. So they’ll put him through the wringer.’

‘Don’t worry. Johnny’s a good kid,’ I said.

‘If he has to choose between deportation to Sri Lanka or spilling his guts, he’ll tell them anything he knows,’ said Werner with stolid logic.

‘He knows nothing,’ I said.

‘He might make some damaging guesses, Bernie.’

‘Shit!’ I rubbed my face and tried to remember anything compromising Johnny might have seen or overheard.

‘Get down, the cops are coming out,’ said Werner. I crouched down on the floor out of sight. There was a strong smell of rubber floor mats. Werner had moved the front seats well forward to give me plenty of room. Werner thought of everything. Under his calm, logical and conventional exterior there lurked an all-consuming passion, if not to say obsession, with espionage. Werner followed the published, and unpublished, sagas of the cold war with the same sort of dedication that other men gave to the fluctuating fortunes of football teams. Werner would have been the perfect spy: except that perfect spies, like perfect husbands, are too predictable to survive in a world where fortune favours the impulsive.

Two uniformed cops walked past going to their car. I heard one of them say, ‘Mit der Dummheit kämpfen Götter selbst vergebens’ – With stupidity the gods themselves struggle in vain.

‘Schiller,’ said Werner, equally dividing pride with admiration.

‘Maybe he’s studying to be a sergeant,’ I said.

‘Someone put a plastic bag over Spengler’s head and suffocated him,’ said Werner after the policemen had got into their car and departed. ‘I suppose he was drunk and didn’t make much resistance.’

‘The police are unlikely to give it too much attention,’ I said. A dead junkie in this section of Kreuzberg was not the sort of newsbreak for which press photographers jostle. It was unlikely to make even a filler on an inside page.

‘Spengler was sleeping on your bed,’ said Werner. ‘Someone was trying to kill you.’

‘Who wants to kill me?’ I said.

Werner wiped his nose very carefully with a big white handkerchief. ‘You’ve had a lot of strain lately, Bernie. I’m not sure that I could have handled it. You need a rest, a real rest.’

‘Don’t baby me along,’ I said. ‘What are you trying to tell me?’

He frowned, trying to decide how to say what he wanted to say. ‘You’re going through a funny time; you’re not thinking straight any more.’

‘Just tell me who would want to kill me.’

‘I knew I’d upset you.’

‘You’re not upsetting me but tell me.’

Werner shrugged.

‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘Everybody says my life is in danger but no one knows from who.’

‘You’ve stirred up a hornet’s nest, Bernie. Your own people wanted to arrest you, the Americans thought you were trying to make trouble for them and God knows what Moscow makes of it all …’

He was beginning to sound like Rudi Kleindorf; in fact, he was beginning to sound like a whole lot of people who couldn’t resist giving me good advice. I said, ‘Will you drive me over to Lange’s place?’

For a moment he thought about it. ‘There’s no one there.’

‘How do you know?’ I said.

‘I’ve phoned him every day, just the way you asked. I’ve sent letters too.’

‘I’m going to beat on his door. Perhaps Der Grosse wasn’t kidding. Maybe Lange is playing deaf: maybe he’s in there.’

‘Not answering the phone and not opening his mail? That’s not like Lange.’ Lange was an American who’d lived in Berlin since it was first built. Werner disliked him. In fact it was hard to think of anyone who was fond of Lange except his long-suffering wife: and she visited relatives several times a year.

‘Maybe he’s going through a funny time too,’ I said.

‘I’ll come with you.’

‘Just drop me outside.’

‘You’ll need a ride back,’ said Werner in that plaintive, martyred tone he used when indulging me in my most excruciating foolishness.

When we reached the street where John ‘Lange’ Koby lived I thought Werner was going to drive away and leave me to it, but the hesitation he showed was fleeting and he waved away my suggestions that I go up there alone.

Dating from the last century it was a great grey apartment block typical of the whole city. Since my previous visit the front door had been painted and so had the lobby, and one side of the entrance hall had two lines of new tin postboxes, each one bearing a tenant’s name. But once up the first staircase all attempts at improvement ceased. On each landing a press-button timer switch provided a dim light and a brief view of walls upon which sprayed graffiti proclaimed the superiority of football teams and pop groups, or simply made the whorls and zigzag patterns that proclaim that graffiti need not be a monopoly of the literate.

Lange’s apartment was on the top floor. The door was old and scuffed, the bell push had had its label torn off as if someone had wanted the name removed. Several times I pressed the bell but heard no sound from within. I knocked, first with my knuckles and then with a coin I found in my pocket.

The coin gave me an idea. ‘Give me some money,’ I told Werner.

Obliging as ever he opened his wallet and offered it. I took a hundred-mark note and tore it gently in half. Using Werner’s slim silver pencil, I wrote ‘Lange – open up you bastard’ on one half of the note and pushed it under the door.

‘He’s not there,’ said Werner, understandably disconcerted by my capricious disposal of his money. ‘There’s no light.’

Werner meant there was no light escaping round the door or from the transom. I didn’t remind him that John Lange Koby had been in the espionage game a very long time indeed. Whatever one thought of him – and my own feelings were mixed – he knew a thing or two about fieldcraft. He wasn’t the sort of man who would pretend he was out of town while letting light escape from cracks around his front door.

I put a finger to my lips and no sooner had I done so than the timer switch made a loud plop and we were in darkness. We stood there a long time. It seemed like hours although it was probably no more than three minutes.

Suddenly the door bolts were snapped back with a sound like gunshots. Werner gasped: he was startled and so was I. Lange recognized that and laughed at us, ‘Step inside folks,’ he said. He held out his hand and I gave it the slap that he expected as a greeting. Only a glimmer of light escaped from his front door. ‘Bernard! You four-eyed son of a bitch!’ Looking over my shoulder he said, ‘And who’s this well-dressed gent with false moustache and big red plastic nose? Can it be Werner Volkmann?’ I felt Werner stiffen with anger. Lange continued, not expecting a reply. ‘I thought you guys were Jehovah’s Witnesses! The hallelujah peddlers been round just about every night this week. Then I thought to myself, “It’s Sunday, it’s got to be their day off!”’ He laughed.

Lange read my written message again and tucked the half banknote into the pocket of his shirt as we went inside. In the entrance there was an inlaid walnut hallstand with a mirror and hooks for coats, a shelf for hats and a rack for sticks and umbrellas. He took Werner’s hat and overcoat and showed us how it worked. It took up almost all the width of the corridor and we had to squeeze past it. I noticed that Lange didn’t switch on the light until the front door was closed again. He didn’t want to be silhouetted in the doorway. Was he afraid of something, or someone? No, not Lange: that belligerent old bastard was fearless. He pushed aside a heavy curtain. The curtain was in fact an old grey Wehrmacht blanket, complete with the stripe that tells you which end is for your feet. It hung from a rail on big wooden rings. It kept the cold draught out and also prevented any light escaping from the sitting room.

They only had one big comfortable room in which to sit and watch television, so Lange used it as his study too. There were bookshelves filling one wall from floor to ceiling, and even then books were double-banked and stuffed horizontally into every available space. An old school-desk near the window held more books and papers and a big old-fashioned office typewriter upon which German newspapers and a cup and saucer were precariously balanced.

‘Look who finally found out where we live,’ Lange said to his wife in the throaty Bogart voice that suited his American drawl. He was a gaunt figure, pens and pencils in the pocket of his faded plaid shirt, and baggy flannel trousers held up by an ancient US army canvas belt.

His wife came to greet us. Face carefully made-up, hair short and neatly combed, Gerda was still pretty in a severe spinsterish style. ‘Bernard dear! And Werner too. How nice to see you.’ She was a diminutive figure, especially when standing next to her tall husband. Gerda was German; very German. They met here in the ruins in 1945. At that time she was an opera singer and I can remember how, years later, she was still being stopped on the street by people who remembered her and wanted her autograph. That was a long time ago, and now her career was relegated to the history books, but even in her cheap little black dress she had some arcane magic that I could not define, and sometimes I could imagine her singing Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier the way she had that evening in 1943 when she brought the Staatsoper audience to its feet and became a star overnight.

‘We tried to phone,’ explained Werner apologetically.

‘You are looking well,’ said Gerda, studying Werner with great interest. ‘You look most distinguished.’ She looked at me. ‘You too, Bernard,’ she added politely, although I think my long hair and dirty clothes disturbed her. ‘Would you prefer tea or coffee?’ Gerda asked.

‘Or wine?’ said Lange.

‘Tea or coffee,’ I said hurriedly. Each harvest Gerda made enough plum wine to keep Lange going all year. I dread to think how much that must have been, for Lange drank it by the pint. It tasted like paint remover.

‘Plum wine,’ said Lange. ‘Gerda makes it.’

‘Do you really, Gerda?’ I said. ‘What a shame. Plum wine brings me out in spots.’

Lange scowled. Gerda said, ‘Lange drinks too much of it. It’s not good for him.’

‘He looks fit on it,’ I pointed out, and considering that this huge aggressive fellow was in his middle seventies, or beyond, was almost enough to convert me to Gerda’s jungle juice.

We sat down on the lumpy sofa while Mrs Koby went off to the kitchen to make some tea for us. Lange hovered over us. He’d not changed much since the last time I’d seen him. In fact he’d changed very little from the ferocious tyrant I’d worked for long long ago. He was a craggy man. I remember someone in the office saying that they’d rather tackle the north face of the Eiger than Lange in a bad mood, and Frank Harrington had replied that there was not much in it. Ever since then I’d thought of Lange as some dangerous piece of granite: sharp and unyielding, his topsoil long since eroded so that his rugged countenance was bare and pitiless.

‘What can I do for you boys?’ he said with the urgent politeness with which a shopkeeper might greet a customer arriving a moment or two before closing time.

‘I need advice, Lange.’

‘Ah, advice. Everybody wants it: nobody takes it. What can I tell you?’

‘Tell me about the Wall.’

‘What do you want to know?’

‘Escaping. I’m out of touch these days. Bring me up to date.’

He stared at me for a moment as if thinking about my request. ‘Forget glasnost,’ said Lange. ‘If that’s what you’ve come here to ask me. No one’s told those frontier guards about glasnost. They are still spending money improving the minefields and barbed wire. Things are still the same over there: they still shoot any poor bastard who looks like he might want to leave their part of town.’

‘So I hear,’ I said.

‘Then where do I start?’

‘At the beginning.’

‘Berlin Wall. About 100 miles of it surrounds West Berlin. Built Sunday morning August 1961 … Hell, Bernard, you were here!’

‘That’s okay. Just tell me the way you tell the foreign journalists. I need to go through it all again.’

A flicker of a smile acknowledged my gibe. ‘Okay. At first the hastily built Wall was a bit ramshackle and it was comparatively easy for someone young, fit and determined to get through.’

‘How?’

‘I remember the sewers being used. The sewers couldn’t be bricked off without a monumental engineering job. One of my boys came through a sewer in Klein-Machnow. A week after the Wall went up. The gooks had used metal fencing so as not to impede the sewage flow. My guys from this side waded through the sewage to cut the grilles with bolt-cutters and got him out. But after that things gradually got tougher. They got sneaky: welded steel grids into position and put alarms and booby-traps down there – put them under the level of the sewage so we couldn’t see them. The only escape using the sewers that I heard of in the last few years were both East German sewage workers who had the opportunity to loosen the grid well in advance.’

‘So then came the tunnels,’ I said.

‘No, at first came all the scramble escapes. People using ladders and mattresses to get across places where barbed wire was the main obstacle. And there were desperate people in those buildings right on the border: leaping from upstairs windows and being caught in a Sprungtuch by obliging firemen. It all made great pictures and sold newspapers but it didn’t last long.’

‘And cars,’ said Werner.

‘Sure cars: lots of cars – remember that little bubble car … some poor guy squeezed into the gas tank space? But they wised up real fast. And they got rid of any Berlin kids serving as Grenztruppen – too soft they said – and brought some real hard-nosed bastards from the provinces, trigger-happy country boys who didn’t like Berliners anyway. They soon made that sort of gimmick impossible.’

‘False papers?’

‘You must know more about that than I do,’ said Lange. ‘I remember a few individuals getting through on all kinds of Rube Goldberg devices. You British have double passports for married couples and that provided some opportunities for amateur label fakers, until the gooks over there started stamping “travelling alone” on the papers and keeping a photo of people who went through the control to prevent the wrong one from using the papers to come back.’

‘People escaped in gliders, hang-gliders, microlites and even hot-air balloons,’ said Werner helpfully. He was looking at me with some curiosity, trying to guess why I’d got Lange started on one of his favourite topics.

‘Oh, sure,’ said Lange. ‘No end of lunatic contraptions and some of them worked. But only the really cheap ideas were safe and reliable.’

‘Cheap?’ I said. I hadn’t heard this theory before.

‘The more money that went into an escape the greater the number of people involved in it, and so the greater the risk. One way to defray the cost was to sell it to newspapers, magazines or TV stations. You could sometimes raise the money that way but it always meant having cameramen hanging around on street corners or leaning out of upstairs windows. Some of those young reporters didn’t know their ass from their elbow. The pros would steer clear of any escapes the media were involved with.’

‘The tunnels were the best,’ pronounced Werner, who’d become interested in Lange’s lecture despite himself.

‘Until the DDR made the 100-metre restricted area, all along their side of the Wall, tunnels were okay. But after that it was a long way to go, and you needed ventilation and engineers who knew what they were doing. And they had to dig out a lot of earth. They couldn’t take too long completing the job or the word would get out. So tunnels needed two, sometimes three, dozen diggers and earth-movers. A lot of bags to fill; a lot of fetching and carrying. So you’re asking too many people to keep their mouths shut. You trust a secret to that many people and, on the law of averages, at least one of them is going to gossip about it. And Berliners like to gossip.’

I said nothing. Mrs Koby came in with the tea. Upon the tray there was a silver teapot and four blue cups and saucers with gilt rims. They might have been heirlooms or a job lot from the flea-market at the old Tauentzienstrasse S-Bahn station. Gerda poured out the tea and passed round the sugar and the little blue plate with four chocolate ‘cigarettes’. Lange got a refill of his plum wine: he preferred that. He took a swig of it and wiped his mouth with a big wine-stained handkerchief.

Lange hadn’t stopped: he was just getting going. ‘Over there, the Wall had become big business. There was a department of highly paid bureaucrats just to administer it. You know how it is: give a bureaucrat a clapboard doghouse to look after and you end up with a luxury zoo complete with an administration office block. So the Wall kept getting bigger and better and more and more men were assigned to it. Men to guard it, men to survey it and repair it, men to write reports about it, reports that came complete with cost-estimates, photos, plans and diagrams. And not just guards: architects, draftsmen, surveyors and all the infrastructure of offices, with clerks who have to have pension schemes and all the rest of it.’

‘You make your point, Lange,’ I said.

He gave no sign of having heard. He poured more wine and drank it. It smelled syrupy, like some fancy sort of cough medicine. I was glad to be allergic to it. He said, ‘Wasteful, yes, but the Wall got to be more and more formidable every week.’

‘More tea, Bernard,’ said Gerda Koby. ‘It’s such a long time since we last saw you.’

If Gerda thought that might be enough to change the subject she was very much mistaken. Lange said, ‘Frank Harrington sent agents in, and brought them out, by the U-Bahn system. I’m not sure how he worked it: they say he dug some kind of little connecting tunnel from one track to the next so he could get out in Stadtmitte where the West trains pass under the East Sector. That was very clever of Frank,’ said Lange, who was not renowned for his praise of anything the Department did.

‘Yes, Frank is clever,’ I said. He looked at me and nodded. He seemed to know that Frank had deposited me into the East by means of that very tunnel.

‘Trouble came when the gooks got wind of it. They staked it out and dumped a pineapple down the manhole just as two of Frank’s people were getting ready to climb out of it. The dispatching officer was blown off his feet … and he was two hundred yards along the tunnel! Frank wasn’t around: he was apple-polishing in London at the time, telling everyone about the coming knighthood that he never got.’

I wasn’t going to talk about Frank Harrington; not to Lange I wasn’t. ‘So the diplomatic cars are the only way,’ I said.

‘For a time that was true,’ said Lange with a wintry smile. ‘I could tell you of African diplomats who put a lot of money into their pockets at ten thousand dollars a trip with an escapee in the trunk. But a couple of years ago they stopped a big black Mercedes with diplomatic plates at Checkpoint Charlie and fumigated it on account of what was described as “an outbreak of cattle disease”. Whatever they used to fumigate that car put paid to a 32-year-old crane operator from Rostock who was locked in the trunk. They say his relatives in Toronto, Canada, had paid for the escape.’

‘The guards opened the trunk of a diplomatic car?’ asked Werner.

‘No. They didn’t have to,’ said Lange grimly. ‘Maybe that poison gas was only intended to give some young escaper a bad headache but when the trunk was opened on this side, the fellow inside was dead. Hear about that, Bernard?’ he asked me.

‘Not the way you tell it,’ I admitted.

‘Well that’s what happened. I saw the car. There were ventilation holes drilled into the trunk from underneath to save an escaper from suffocating. The guards must have known that, and known where the vents were.’

‘What happened?’ asked Werner.

‘The quick-thinking African diplomat turned around and took the corpse back to East Berlin and into his embassy. The corpse became an African national by means of pre-dated papers. Death in an embassy: death certificate signed by an African medico so no inquiries by the East German police. Quiet funeral. Buried in a cemetery in Marzahn. But here’s the big boffola: not knowing the full story, some jerk working for the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Volkskammer thinks a gesture of sympathy is required. So – on behalf of the government and people of the DDR – they send an enormous wreath in which the words “peace, trust and friendship” are made from miniature roses. It was only on the grave for a day or two then it was discreetly removed by someone from the Stasi.’ Lange laughed loudly. ‘Cheer up, Bernie,’ he said and laughed some more.

‘I thought you’d have good news for me, Lange. I thought things had eased up.’

‘And don’t imagine going through Hungary or Czechoslovakia is any easier. It’s tight everywhere. When you read how many people have been killed crossing the Wall you should add on the hundreds that have quietly bled to death somewhere out of sight on the other side.’

‘That’s good tea, Gerda,’ I said. I never knew whether to call her Mrs Lange or Gerda. She was one of those old-fashioned Germans who prefer all the formalities: on the other hand she was married to Lange.

‘Bringing someone out, Bernie?’ said Lange. ‘Someone rich, I hope. Someone who can pay.’

‘Werner’s brother-in-law in Cottbus,’ I said. ‘No money, no nothing.’

Werner, who knew nothing of any brother-in-law in Cottbus, looked rattled but he recovered immediately and backed me up gamely. ‘I’ve promised,’ said Werner and sat back and smiled unconvincingly.

Lange looked from one of us to the other. ‘Can he get to East Berlin?’

‘He’ll be here with his son,’ Werner improvised. ‘For the Free German Youth festival in summer.’

Lange nodded. Werner was a far better liar than I ever imagined. I wondered if it was a skill that he’d developed while married to the shrewish Zena. ‘You haven’t got a lot of time then,’ said Lange.

‘There must be a way,’ said Werner. He looked at his watch and got to his feet. He wanted to leave before I got him more deeply involved in this fairy tale.

‘Let me think about it,’ said Lange as he got Werner’s coat and hat. ‘You didn’t have an overcoat, Bernie?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Aren’t you cold, Bernard?’ said Gerda.

‘No, never,’ I said.

‘Leave him alone,’ said Lange. He opened the door for us but before it was open wide enough for us to leave he said, ‘Where’s the other half of that banknote, Bernard?’

I gave it to him.

Lange put it in his pocket and said, ‘Half a banknote is no good to anybody. Right, Bernie?’

‘That’s right, Lange,’ I said. ‘I knew you’d quickly tumble to that.’

‘There’s a lot of things I quickly tumble to,’ he said ominously.

‘Oh, what else?’ I said as we went out.

‘Like there not being a Freie Deutsche Jugend festival in Berlin this summer.’

‘Maybe Werner got it wrong,’ I said. ‘Maybe it was the Gesellschaft für Sport und Technik that have their Festival in East Berlin this summer.’

‘Yeah,’ said Lange, calling after us in that hoarse voice of his, ‘and maybe it’s the CIA having a gumshoe festival in West Berlin this summer.’

‘Berlin is wonderful in the summer,’ I said. ‘Just about everyone comes here.’

I heard Lange close the door with a loud bang and slam the bolts back into place with a display of surplus energy that is often the sign of bad temper.

As we were going downstairs Werner said, ‘Is it your wife Fiona? Are you going to try to get her out?’

I didn’t answer. The time switch plopped and we continued downstairs in darkness.

Vexed at my failure to answer him, Werner said somewhat petulantly, ‘That was my hundred marks you gave Lange.’