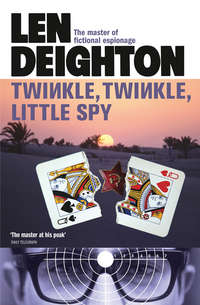

Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘I say – old chap,’ said the old man. He had difficulty remembering our names. Perhaps that was because we changed them so often. ‘Mr Antony, I mean. Are you wondering about the road ahead?’

‘Yes,’ I said. My name was Antony; Frederick L. Antony, tourist.

Dempsey blinked. His face was soft and babyish as old men’s faces sometimes are. Now that he had taken off his sun-glasses, his blue eyes became watery.

Mann said, ‘Don’t get nervous, Auntie. We’ll dope it out.’

‘The oil-drum markers continue along this track,’ said the old man.

‘How do you know that?’ said Mann.

‘I can see them,’ said the old man.

‘Yeah!’ said Mann. ‘So how come I can’t see them, and my buddy here can’t see them?’

‘I used my binoculars,’ said the old man apologetically.

‘Why the hell didn’t you say you had binoculars?’ said Mann.

‘I offered them to you just outside Oran. You said you weren’t planning a trip to the opera.’

‘Let’s go,’ said Mann. ‘I want to make camp before the sun gets high. And we have to find a place where the Russkie can spot us from the main road.’

Dempsey’s Desert Tours VW bus was equipped with two tent sides that expanded to provide a large area of shade. There was also a nylon sheet stretched across the roof, and held taut above it, which prevented the direct sunlight striking the top of the bus and so making it into the kind of oven that metal car bodies became.

The bright orange panels could be seen for miles. The Russian spotted them easily. He had driven non-stop from some prospecting site along the river Niger east of Timbuktu. It was a gruelling journey over poor tracks and open country, and he’d ended it in the fierce heat of early afternoon.

The Russian was a hatchet-faced man in his early forties.

He was tall and slim with cropped black hair that showed no sign of greying. His dark suit was baggy and stained, its jacket slung over his brawny shoulder. His red check shirt was equally dirty, and the gold pencil clipped into its pocket was conspicuous because of that. Pale blue eyes were almost sealed by fine desert sand, and his face was lined and bore the curious bruise-like marks that come with exhaustion. His arms were muscular and his skin was tanned very dark.

Major Mann opened the nylon flap and indicated the passenger seats of the VW bus and the table-top fixed between them. In spite of the tinted windows the plastic seat covering was hot to the touch. I sat opposite the Russian and watched him take off his sun-glasses, yawn and scratch the side of his nose with his car-key.

It was typical of Mann’s cunning, and of his training, that he offered the Russian no chance to rest. Instead he pushed towards him a glass and a vacuum flask containing ice-cubes and water. There was a snap as Mann broke the cap on a half-bottle of whisky and poured a generous measure for our guest. The Russian looked at Mann and gave him a thin smile. He pushed the whisky aside and from the flask grabbed a handful of ice-cubes and rubbed them on his face.

‘You got ID?’ Mann asked. As if to save face he poured whisky for himself and for me.

‘What are ID?’

‘Identification. Passport, security pass or something.’

The Russian took a wallet from his hip pocket. From it he brought a dog-eared piece of brown cardboard with his photo attached. He passed it to Mann, who handed it to me. It was a pass into the military zone along the Mali frontier with Niger. It described the Russian’s physical characteristics and named him as Professor Andrei Mikhail Bekuv. Significantly the card was printed in Russian and Chinese as well as Arabic. I gave it back to him.

‘You have the photo of my wife?’

‘It would have been poor security to risk it,’ said Mann. He sipped at his drink but when he set it down again the level seemed unchanged.

Professor Bekuv closed his eyes. ‘It’s fifteen months since I last saw her.’

Mann shifted uncomfortably in his seat. ‘She will be in London by the time we get there.’

Bekuv spoke very quietly, as if trying to keep a terrible temper under control. ‘Your people promised a photo of her – standing in Trafalgar Square.’

‘It was …’

‘That was the agreement,’ said Bekuv, ‘and you haven’t kept to it.’

‘She never left Copenhagen,’ said Mann.

Bekuv was silent for a long time. ‘Was she on the ship from Leningrad?’ he said finally. ‘Did you check the passenger list?’

‘All we know is that they didn’t come in on the plane to London,’ said Mann.

‘You lie,’ said Bekuv. ‘I know the sort of people you are. My country is filled with such men as you. You had men there waiting for her.’

‘She will come,’ said Mann.

‘Without her I will not come with you.’

‘She will come,’ said Mann. ‘She is probably there already.’

‘No,’ said Bekuv. He turned in his seat, to see the road that would take him a thousand miles back to the Russians in Timbuktu. In spite of the tinted windows, the sand was no more than a blinding glare. Bekuv picked up the battered sun-glasses that he’d left on the table alongside his car keys. He toyed with them for a moment and then put them into the pocket of his shirt. ‘Without her I am nothing,’ said Bekuv reflectively. ‘Without her life is not worth living for me.’

Mann said, ‘There is urgent work to be done, Professor Bekuv. Your chair of Interstellar Communication at New York University will give you access time on the Jodrell Bank radio telescope – and, as you well know, that has a 250-foot steerable paraboloid. The university is also arranging time on the 1,000-foot fixed radio telescope they’ve built in the Puerto Rican mountains near Arecibo.’

Bekuv didn’t answer but he didn’t leave either. I glanced at Mann and he gave me the sort of glare that was calculated to shrivel me to silent tissue. I realized now that Mann’s joke about little men in flying saucers was no joke.

‘There is no one else doing this kind of cosmology,’ Mann said. ‘Even if you fail to make contact with life in other solar systems, you’ll be able to give it a definitive thumbs down.’

Bekuv looked at him scornfully. ‘There is already enough – proof to satisfy any but the most stupid.’

‘If you don’t take this newly created chair of Interstellar Communication there will be another bitter fight … and next time the cynics might get their nominee into it. Professor Chataway or old Delahousse would jump at such an opportunity to prove that there was no life anywhere in outer space.’

‘They are fools,’ said Bekuv.

Mann pulled a face and shrugged.

Bekuv said, ‘I have a beautiful wife who has remained faithful, a proud mother and a talented son who will soon be at university. Nothing is more important than they are.’

Mann sipped some of his whisky and this time he really drank. ‘Suppose you go back to Timbuktu and your wife is waiting in London? What then, eh?’

‘I’ll take that chance,’ said Bekuv. He slid across the seat and stepped down from the VW into the sand. The light through the nylon side-panels coloured him bright orange.

Mann didn’t move.

‘You don’t fool me,’ said Mann. ‘You’re not going anywhere. You made your decision a long time ago and you’re stuck with it. You go back now, and your comrades will stake you out in the sand, and toss stale piroshkis at you.’

Bekuv said nothing.

‘Here, you forgot your car keys, buddy,’ Mann taunted him.

Bekuv took the keys that Mann offered but he did not step out into the sunshine. The sudden buzzing of a fly sounded unnaturally.

‘Professor Bekuv,’ I said. ‘It’s in our mutual interests that your family should be with you.’

Bekuv took out his hankerchief and wiped sand from the corners of his eyes but he gave no sign of having heard me.

‘I understand there is still work to be done, so you can bet that the American Government will do everything in their power to make sure you are happy in every respect.’

‘In their power, yes …’ said Bekuv sadly.

‘There are ways,’ I said. ‘There are official swops as well as escapes. And what you never hear about are the secret deals that our governments do. The trade agreements, the loans, the grain sales … all these deals contain hundreds of secret clauses. Many of them involve people we exchange.’

Bekuv dug the toe of his high, laced boots into the sand and traced a pattern of criss-cross lines. Mann reached forward from his seat and rested a hand upon Bekuv’s shoulder. The Russian twitched nervously.

‘Look at it this way, Professor,’ Mann said, in the sort of voice that he believed to be gentle and conciliatory. ‘If your wife is free we’ll bring her to you, so you might as well come with us.’ Mann paused. ‘If she’s in prison … you’d be out of your mind to go back.’ He tapped Bekuv’s shoulder again. ‘That’s the way it goes, Professor Bekuv.’

‘There was no letter from her this week,’ said Bekuv.

Mann looked at him but said nothing.

I had seen it before: men like Bekuv are ill fitted for the conspiracy of defection, let alone years of conspiracy that threatened the safety of his family. His gruelling journey across the Sahara had exhausted him. But his worst mistake was in looking forward to the moment when it would all be over; professionals never do that. ‘Oh Katinka!’ whispered Bekuv. ‘And my fine son. What have I done to you. What have I done.’

I didn’t move, and neither did Mann, but Bekuv pushed the nylon flap aside and stepped out into the scorching sun. He stood there for a long time.

3

The next problem was how to lose Bekuv’s vehicle. It was a GAZ 59A, a Russian four-wheel drive field-car. It was a conspicuous contraption – canvas top, angular bodywork and shiny metal springs showing through the seat covers. You couldn’t bury it in sand, and setting it ablaze would probably attract just the sort of attention we were trying to avoid.

Mann took a big wrench and ripped the registration plates off it and defaced the RMM sign that would tell even an illiterate informer that it was from Mali.

Mann didn’t trust Percy Dempsey out of his sight. And Mann certainly didn’t trust Johnny, the ever-smiling Arab driver. Only because he couldn’t come up with a better idea did he agree to Johnny heading back north with the GAZ, while we followed with Bekuv in the VW. And all the time he was turning to look at Bekuv, watching Percy in the Land Rover behind us and telling me that Percy Dempsey wasn’t half the man I’d cracked him up to be.

‘It’s damned hot,’ I said.

Mann grunted and looked at Bekuv still asleep on the bench seat behind us. ‘If we dump that GAZ anywhere here in the south, the cops will check it to make sure it’s not someone dying of thirst. But the farther we go north, the more interest the cops are going to take in that funny-looking contraption.’

‘We’ll be all right.’

‘We haven’t seen one of those heaps in the whole of Algeria.’

‘Stop worrying,’ I said. ‘Percy was doing this kind of thing out here in the desert when Rommel was in knee pants.’

‘You Limeys always stick together.’

‘Why don’t you drive for a while, Major.’

When we stopped to change seats, we stayed there long enough to let Johnny get a few kilometres ahead. The GAZ was no record-breaker. It wasn’t all that far advanced from the Model A Ford from which it evolved. There would be no problem catching up with it, even in the VW.

In fact, the old GAZ came into view within twenty-five minutes of us resuming the journey. We saw it surmounting the gentle slope of a dune and Mann flicked his headlights in greeting.

‘We’ll keep this kind of distance,’ Mann said. There was about five hundred yards between the vehicles.

Behind us Percy came into view, driving the Land Rover. ‘Is Percy a fag?’ said Mann.

‘Queer?’ I said. ‘Percy and Johnny? I never gave it a thought.’

‘Percy and Johnny,’ said Mann. ‘It sounds like some cosy little bar in Tangier.’

‘Does that make it more likely that they are queers, or less likely?’

‘As long as they do their job,’ said Mann. ‘That’s all I ask.’ He glanced in the mirror before taking a packet of Camels from his shirt pocket, extracting a cigarette and lighting up, without letting go of the wheel. He inhaled and blew smoke before speaking again. ‘Just get us up to that goddamned airstrip, that’s all I ask.’ He thumped the steering-wheel with his bony fist. ‘That’s all I ask.’

I smiled. The first hint of Bekuv’s possible defection had been made to a British scientist. That meant that British Intelligence were going to cling to this one like a limpet. I was the nominated limpet, and Mann didn’t like limpets.

‘We should have moved by night,’ I said, more to make conversation than because I’d thought about it very carefully.

‘And what do we tell the cops, that we are photographing moths?’

‘No explanation necessary,’ I said. ‘These roads probably have more traffic at night when it’s cool. The danger is running into camels or people walking.’

‘Look at tha – Jesus Christ!’

Mann was staring ahead but I could see nothing there, and by the time I realized he was looking in the rear-view mirror it was too late. Mann was wrenching the steering-wheel and we were jolting into the desert in a cloud of sand. There was a howl of fury as Bekuv was shaken off the back seat and hit the floor.

I heard the jet helicopter long before I caught sight of it. I was still staring at the GAZ, watching it disappear in a flurry of sand and white flashes. Then it became a big molten blob that swelled up, and, like a bright red balloon, the fuel exploded with a terrible bang.

The helicopter’s whine turned to a thudding of rotor blades as it came back and flew over us with only a few feet clearance, its blades chopping Indian signals out of the smoke that drifted up from the GAZ.

The Plexiglas bubble flashed in the sun as it banked so close to the desert that the blade tips almost touched the dunes. It was out of sight for a moment and by the time I heard the engine again I was fifty yards from the track full length on my face and trying to bury my head in the sand.

The pilot turned tightly as he came to the roadway. He circled the burning car and then came back again before he was satisfied about his task. He turned his nose eastwards. At that altitude he was out of sight within a second or two.

‘How did you guess?’ I asked Mann.

‘The way he was sitting there above the road. I’ve seen gun-ships in Nam. I knew what he was going to pull.’ He smacked the dust off his trousers. ‘OK, Professor?’

Bekuv nodded grimly. Obviously it had removed any last thoughts he might have had about driving back to Mali to kiss and make up.

‘Then let’s get the hell out of here, before the cops arrive to mop up the mess.’

We slowed as we passed through the smoke and the stink of rubber and carbonized flesh. Bekuv and I both turned to make sure that there was no last chance that the boy could have survived it. Then Mann accelerated, but behind us we saw the Land Rover stop.

Mann was looking in the rear-view mirror. He saw it too. ‘What’s the old fool stopping for?’

I didn’t answer.

‘You got cloth ears?’

‘To bury the kid.’

‘He can’t be that dumb!’

‘There are traditions in the desert,’ I said.

‘You mean that’s what the dummy is going to tell the cops when they get here and find him carving a headstone.’

‘Probably.’

‘They’ll shake him,’ said Mann. ‘The cops will shake Percy Dempsey, and you know what will fall out of his pockets?’

‘Nothing will.’

‘We will!’ said Mann, still watching in the mirror. ‘Goddamned stupid fruit.’

‘I make it twenty k.’s to the turn-off for the airstrip.’

‘Unless our fly-boy was scared shitless by that gunship, and went back to Morocco again.’

‘Our boy hasn’t even faked his flight plan yet,’ I said. ‘He’s only fifteen minutes’ flying time away from here.’

‘OK, OK, OK,’ said Mann. ‘I don’t need any of that Dunkirk spirit crap.’ For a long time we drove in silence.

‘Watch for that cairn at the turn-off,’ I said. ‘It’s no more than half a dozen stones, and the sand has drifted since we came down this road.’

‘There’s no spade in the Land Rover,’ said Mann. ‘You don’t think he’d bury him with his bare hands, do you.’

‘Slow a little now,’ I said. ‘The cairn is on this side.’

An aircraft came dune-hopping in from the north-west. It was one of a fleet of Dornier Skyservant short-haul machines, contracted to take Moroccan civil servants, politicians and technicians down to the phosphate workings near the Algerian border. The world demand for phosphates had made the workings the most pampered industry in Morocco.

The pilot landed at the first approach. It was part of his job to be able to land on any treeless piece of hard dirt. The Dornier taxied over to us and flipped the throttle of the port engine, so that it turned on its own axis, and was ready to fly out again. ‘Watch out for the prop-wash!’ Mann warned me.

Mann’s father had been an airline pilot, and Mann had a ten-year subscription to Aviation Week. Flying machines brought out the worst in him. He rapped the metal skin of this one before climbing through the door. ‘Great ships, these Dorniers,’ he told me. ‘Ever see a Dornier before?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘My uncle George shot one down in 1940.’

‘Just make sure you lock the door,’ said Mann.

‘Let’s go, let’s go,’ said the pilot, a young Swede with a droopy moustache and ‘Elsa’ tattooed on his bicep.

I pushed Bekuv ahead of me. There were a dozen or more seats in the cabin, and Mann had already planted himself nearest the door.

‘Hurry!’ said the pilot. ‘I want to get back on to my flight plan.’

‘Casablanca?’ said Mann.

‘And all the couscous you can eat,’ said the pilot, and he opened the throttles even before I had locked the door.

The place from which the twin-engined Dornier climbed steeply was a disused site left by the road-builders. There were the usual piles of oil-drums, two tractor chassis and some stone markers. Everything else had been taken by the nomads. Now a bright new VW bus marked Dempsey Desert Tours was parked in the shallow depression of a wadi.

‘That’s screwed this one up for ever,’ said Mann. ‘When the cops find the VW they’ll be watching this airstrip for ever.’

‘Dempsey will collect it,’ I said.

‘He’s a regular little Lawrence of Arabia, your pal Dempsey.’

‘He could have done this job on his own,’ I said. ‘There was no need for us to come down here.’

‘You’re even dumber than you look.’ Mann looked round to make sure that Bekuv couldn’t hear.

‘Why then …?’

‘Because if the prof yells loud enough for his spouse, someone is going to have to go in and get her.’

‘They’ll use one of the people in the field,’ I said.

‘They’ll use someone who talked to the professor … and you know it! Someone who was here, who can talk to his old lady and make it sound convincing.’

‘Bloody risky,’ I said.

‘Yep!’ said Mann. ‘If the Russkies are going to send gun-ships here and blast cars out of the desert, they are not going to let his old lady out of their clutches without a struggle.’

‘Perhaps they’ll write Bekuv off as dead,’ I said.

Mann turned in his seat to look at the professor. His head was thrown back over the edge of the seat-back. His mouth was open and his eyes closed. ‘Maybe,’ said Mann.

Now I could see the mountains of the High Atlas. They were almost hidden behind the shimmer of heat that rose from the colourless desert below us, but above the heat haze I could distinguish the snow-capped tops of the highest peaks. Soon we’d see the Atlantic Ocean.

4

I never discovered whether New York University realized that they had acquired a chair of Interstellar Communication; certainly it was not mentioned in the press analysis. The house we used was on Washington Square, facing across the trees to the university buildings. It had been owned by the CIA – through a land-management front – for many years, and used for various clandestine purposes that included extra-marital exploits by certain senior members of the Operations Division.

Technically, Major Mann was responsible for Bekuv’s safety – which was a polite way of saying custody, as Bekuv himself pointed out at least three times a day. But it was Mann’s overt role of custodian that enabled Bekuv to believe that the interrogation team were the NYU academics that they pretended to be. The interrogators’ first hurdle was to steer Bekuv away from pure administration. Perhaps it was inevitable that a Soviet academic would want to know the floor-area his department would occupy, spending restrictions, the secretarial staff he was entitled to, his voting power in the university, his access to printing, photography and computer and his priority for student and postgraduate enrolment.

The research team was becoming more and more fretful. The reported leakage of scientific information eastwards was reflected by the querulous memos that were piling up in my ‘classified incoming’.

Pretending to be Professor Bekuv’s assistants, the interrogators were hoping to recognize the character of the data he already knew, and hoping to trace the American sources from which it had been stolen. With this in mind, slightly modified data had been released to selected staff at various government labs. So far, none of this ‘seeded’ material had come back through Bekuv, and now, in spite of strenuous protests from his ‘staff’, Bekuv declared a beginning to the Christmas vacation. He imperiously dismissed his interrogators back to their homes and families. Bekuv was therefore free to spend all his days designing a million-dollar heap of electronic junk that was guaranteed to make contact with one of those super-civilizations that were sitting around in space waiting to be introduced.

By Thursday evening the trees in Washington Square were dusted with the winter’s first snow, radio advertisers were counting Christmas shopping time in hours, and Mann was watching me shave in preparation for a Park Avenue party at the home of a senior security official of the United Nations. A hasty note on the bottom of the engraved invitation said ‘and bring the tame Russkie’. It had sent Mann into a state of peripatetic anxiety. ‘You say Tony Nowak sent your invite to the British Embassy in Washington?’ he asked me for the fourth or fifth time.

‘You know Tony,’ I said. ‘He’s nothing if not tactful. That’s his UN training.’

‘Goddamned gab-factory.’

‘You think he knows about this house on Washington Square?’

‘We’ll move Bekuv tomorrow,’ said Mann.

‘Tony can keep his mouth shut,’ I said.

‘I’m not worrying about Tony,’ said Mann. ‘But if he knows we’re here, you can bet a dozen other UN people know.’

‘What about California?’ I suggested. ‘UCLA.’ I sorted through my last clean linen. I was into my wash-and-wear shirts now, and the bath was brimming with them.

‘And what about Sing Sing?’ said Mann. ‘The fact is that I’m beginning to think that Bekuv is stalling – deliberately – and will go on stalling until we produce his frau.’

‘We both guessed that,’ I said. I put on a white shirt and club tie. It was likely to be the sort of party where you were better off English.

‘I’d tear the bastard’s toenails out,’ Mann growled.

‘Now you don’t mean that,’ I said. ‘That’s just the kind of joke that gets you a bad reputation.’

I got a sick kind of pleasure from provoking Major Mann, and he rose to that one as I knew he would: he stubbed out his cigar and dumped it into his Jim Beam bourbon – and you have to know Mann to realize how near that is to suicide. Mann watched me combing my hair, and then looked at his watch. ‘Maybe you should skip the false eyelashes,’ he said, ‘we’re meeting Bessie at eight.’