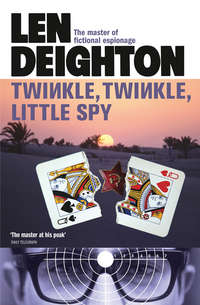

Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

Mann’s wife Bessie looked about twenty years old but must have been nearer forty. She was tall and slim, with the fresh complexion that was the product of her childhood on a Wisconsin farm. If beautiful was going too far, she was certainly good-looking enough to turn all male heads as she entered the Park Avenue apartment where the party was being held.

Tony greeted us and adroitly took three glasses of champagne from the tray of a passing waiter. ‘Now the party can really begin,’ said Tony Nowak – or Nowak the Polack as he was called by certain acquaintances who had not admired his spike-booted climb from rags to riches. For Antoni Nowak’s job in the United Nations Organization security unit didn’t require him to be in the lobby wearing a peaked cap and running metal detectors over the hand baggage. Tony had a six-figure salary and a three-window office with a view of the East River, and a lot of people typing letters in triplicate for him. In UN terms he was a success.

‘Now the party can really begin,’ said Tony again. He kissed Bessie, took Mann’s hat and punched my arm. ‘Good to see you – and Jesus, what a tan you guys got in Miami.’

I nodded politely and Mann tried to smile, failed and put his nose into his champagne.

‘The story is you’re retiring, Tony,’ said Bessie.

‘I’m too young to retire, Bessie, you know that!’ He winked at her.

‘Steady up, Tony,’ said Bessie, ‘you want the old man to catch on to us?’

‘He should never have left you behind on that Miami trip,’ said Tony Nowak.

‘It’s a lamp,’ said Mann. ‘Bloomingdales Fifty-four ninety-nine, with three sets of dark goggles.’

‘You could have fooled me,’ said Tony Nowak, ‘I thought it was a spray job.’

Behind us there were soft chiming sounds and a servant opened the door. Tony Nowak was still gripping Bessie’s arm but as he caught sight of his new guests he relaxed his grip. ‘These are the people from the Secretariat …’ said Tony Nowak.

‘Go look after your new arrivals,’ said Mann. ‘Looks like Liz Taylor needs rescuing from the Shah of Iran.’

‘And ain’t you the guy to do it,’ said Tony Nowak. He smiled. It was the sort of joke he’d repeat between relating the names of big-shots who had really been there.

‘It beats me why he asked us,’ I told Mann.

Mann grunted.

‘Are we here on business?’ I asked.

‘You want overtime?’

‘I just like to know what’s going on.’

From a dark corner of the lounge there came the hesitant sort of music that gives the pianist time for a gulp of martini between bars. When Mann got as far as the Chinese screen that divided this room from the dining-room, he stopped and lit a cheroot. He took his time doing it so that both of us could get a quick look round. ‘A parley,’ Mann said quietly.

‘A parley with who?’

‘Exactly,’ said Mann. He inhaled on his cheroot, and took my arm in his iron grip while telling about all the people he recognized.

The dining-room had been rearranged to make room for six special backgammon tables at which silent players played for high stakes. The room was crowded with spectators, and there was an especially large group around the far table at which a middle-aged manufacturer of ultrasonic intruder alarms was doing battle with a spectacular redhead.

‘Now that’s the kind of girl I could go for,’ said Mann.

Bessie punched him gently in the stomach. ‘And don’t think he’s kidding,’ she told me.

‘Don’t do that when I’m drinking French champagne,’ said Mann.

‘Is it OK when you’re drinking domestic?’ said Bessie.

Tony Nowak came past with a magnum of Heidsieck. He poured all our glasses brimful with champagne, hummed the melody line of ‘Alligator Crawl’ more adroitly than the pianist handled it, and then did a curious little step-dance before moving on to fill more glasses.

‘Tony is in an attentive mood tonight,’ I said.

‘Tony is keeping an eye on you,’ said Bessie. ‘Tony is remembering that time when you two came here with those drunken musicians from the Village and turned Tony’s party into a riot.’

‘I still say it was Tony Nowak’s rat-fink cousin Stefan who put the spaghetti in the piano,’ said Mann.

Bessie smiled and pointed at me. ‘The last time we talked about it, you were the guilty party,’ she confided.

Mann pulled a vampire face, and tried to bite his wife’s throat. ‘Promises, promises,’ said Bessie and turned to watch Tony Nowak moving among his guests. Mann walked into the dining-room and we followed him. It was all chinoiserie and high camp, with lanterns and gold-plated Buddhas, and miniature paintings of oriental pairs in acrobatic sexual couplings.

‘It’s Red Bancroft,’ said Mann, still looking at the redhead. ‘She’s international standard – you watch this.’

I followed him as he elbowed his way to a view of the backgammon game. We watched in silence. If this girl was playing a delaying game, it was far, far beyond my sort of backgammon, where you hit any blot within range and race for home. This girl was even leaving the single men exposed. It could be a way of drawing her opponent out of her home board but she wasn’t yet building up there. She was playing red, and her single pieces seemed scattered and vulnerable, and two of her men were out, waiting to come in. But for Mann’s remark, I would have seen this as the muddled play of a beginner.

The redhead smiled as her middle-aged opponent reached for the bidding cube. He turned it in his fingers as if trying to find the odds he wanted and then set it down again. I heard a couple of surprised grunts behind me as the audience saw the bid. If the girl was surprised too she didn’t show it. But when she smiled again, it was too broad a smile; and it lasted too long. Backgammon is as much a game of bluff as of skill and luck, and the redhead yawned and raised a hand to cover her mouth. It was a gesture that showed her figure to good advantage. She gave a nod of assent. The man rattled the dice longer than he’d done before, and I saw his lips move as if in prayer. He held his breath while they rolled. If it was a prayer, it was answered quickly and fully – double six! He looked up at the redhead. She smiled as if this was all part of her plan. The man took a long time looking at the board before he moved his men.

She picked up her dice, and threw them carelessly, but from this moment the game changed drastically. The man’s home board was completely open, so she had no trouble in bringing in her two men. With her next throw she began to build up her home board, which had been littered with blots. A four and a three. It was all she needed to cover all six points. That locked her opponent. Now he could only use a high throw, and for this his prayers were unanswered. She had the game to herself for throw after throw. The man lit a cigar with studied care as he watched the game going against him, and could do nothing about it. Only after she began bearing-off did he get moving again.

Now the bidding cube was in her hands – and that too was a part of the strategy – she raised it. The man looked at the cube, and then up to the faces of his friends. There had been side wagers on his success. He smiled, and nodded his agreement to the new stakes, although he must have known that only a couple of high doubles could save him now. He picked up the dice and shook them as if they might explode. When they rolled to a standstill there was a five and a one on the upper side. He still hadn’t got all his men into the home board. The girl threw a double five – with five men already beared-off, it ended the game.

He conceded. The redhead smiled as she tucked a thousand dollars in C notes into a crocodile-skin wallet with gold edges. The bystanders drifted away. The redhead looked up at Bessie and smiled, and then she smiled at Major Mann too.

But for that Irish colouring she might have been Oriental. Her cheekbones were high and flat and her mouth a little too wide. Her eyes were a little too far apart, and narrow – narrower still when she smiled. It was the smile that I was to remember long after everything else about her had faded in my memory. It was a strange, uncertain smile that sometimes mocked and sometimes chided but was nonetheless beguiling for that, as I was to find to my cost.

She wore an expensive knitted dress of striped autumnal colours and in her ears there were small jade earrings that exactly matched her eyes. Bessie brought her over to where I was standing, near the champagne, and the food.

When Bessie moved away, the girl said, ‘Pizza is very fattening.’

‘So is everything I like,’ I said.

‘Everything?’ said the girl.

‘Well … damn nearly everything,’ I said. ‘Congratulations on your win.’

She got out a packet of mentholated cigarettes and put one in her mouth. I lit it for her.

‘Thank you kindly, sir. There was a moment when he had me worried though, I’ll tell you that.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘When you yawned.’

‘It’s nerves – I try everything not to yawn.’

‘Think yourself lucky,’ I said. ‘Some people laugh when they are nervous.’

‘Do you mean you laugh when you are nervous?’

‘I’m advised to reserve my defence,’ I told her.

‘Ah, how British of you! You want to know my weaknesses but you’ll not confide any of your own.’

‘Does that make me a male chauvinist pig?’

‘It shortens the odds,’ she said. Then she found herself stifling a yawn again. I laughed.

‘How long have you known the Manns?’ I asked.

‘I met Bessie at a Yoga class, about four years back. She was trying to lose weight, I was trying to lose those yawns.’

‘Now you’re kidding.’

‘Yes. I went to Yoga after …’ She stopped. It was a painful memory. ‘… I got home early one night and found a couple of kids burglarizing my apartment. They gave me a bad beating and left me unconscious. When I left hospital I went to a Yoga farm to convalesce. That’s how I met Bessie.’

‘And the backgammon?’

‘My father was a fire chief – Illinois semi-finalist in the backgammon championships one year. He was great. I almost paid my way through college on what I earned playing backgammon. Three years ago I went professional – you can travel the world from tournament to tournament, there’s no season. Lots of money – it’s a rich man’s game.’ She sighed. ‘But that was three years ago. I’ve had a lousy year since then. And a lousy year in Seattle is a really lousy year, believe me! And what about you?’

‘Nothing to tell.’

‘Ah, Bessie told me a lot already,’ she said.

‘And I thought she was a friend.’

‘Just the good bits – you’re English …’

‘How long has that been a “good bit” among the backgammon players of Illinois?’

‘You work with Bessie’s husband, in the analysis department of a downtown bank that I’ve never heard of. You –’

I put my fingers to her lips to stop her. ‘That’s enough,’ I said. ‘I can’t stand it.’

‘Are your family here in the city with you?’ She was flirting. I’d almost forgotten how much I liked it.

‘No,’ I said.

‘Are you going to join them for Christmas?’

‘No.’

‘But that’s terrible.’ Spontaneously she reached out to touch my arm.

‘I have no immediate family,’ I confessed.

She smiled. ‘I didn’t like to ask Bessie. She’s always matchmaking.’

‘Don’t knock it,’ I said.

‘I’m not lucky in love,’ she said. ‘Just in backgammon.’

‘And where is your home?’

‘My home is a Samsonite two-suiter.’

‘It’s a well-known address,’ I said. ‘Why New York City?’

She smiled. Her very white teeth were just a fraction uneven. She sipped her drink. ‘I’d had enough of Seattle,’ she said. ‘New York was the first place that came to mind.’ She put the half-smoked cigarette into an ashtray and stubbed it out as if it was Seattle.

From the next room the piano player drifted into a sleepy version of ‘How Long Has This Been Going On?’ Red moved a little closer to me and continued to stare into her drink like a crystal-gazer seeking a fortune there.

The intruder alarm manufacturer passed us and smiled. Red took my arm and rested her head on my shoulder. When he was out of earshot she looked up at me. ‘I hope you didn’t mind,’ she said. ‘I told him my boy-friend was here; I wanted to reinforce that idea.’

‘Any time.’ I put my arm round her waist; she was soft and warm and her shiny red hair smelt fresh as I pressed close.

‘Some of these people who lose money at the table think they might get recompense some other way,’ she murmured.

‘Now you’ve started my mind working,’ I said.

She laughed.

‘You’re not supposed to laugh,’ I said.

‘I like you,’ she said and laughed again. But now it was a nice throaty chuckle rather than the nervous teeth-baring grimace that I’d seen at the backgammon table.

‘Yes, you guessed right,’ she said. ‘I ran from a lousy love-affair.’ She moved away but not too far away.

‘And now you’re wondering if you did the right thing,’ I said.

‘He was a bastard,’ she said. ‘Other women … debts that I had to pay … drinking bouts … no, I’m not wondering if I did the right thing. I’m wondering why it took me so long.’

‘And now he phones you every day asking you to come back.’

‘How did you know.’ She mumbled the words into my shoulder.

‘That’s the way it goes,’ I said.

She gripped my arm. For a long time we stood in silence. I felt I’d known her all my life. The intruder alarm man passed again. He smiled at us. ‘Let’s get out of here,’ she said.

There was nothing I would have liked better but Mann had disappeared from the room, and if he was engaged in the sort of parley he’d anticipated, he’d be counting on my standing right here with both eyes wide open.

‘I’d better stay with the Manns,’ I told her. She pursed her lips. And yet a moment later she smiled and there was no sign of the scarred ego.

‘Sure,’ she said. ‘I understand,’ but she didn’t understand enough, for soon after that she saw some people she knew and beckoned them to join us.

‘Do you play backgammon?’ one of the newcomers asked.

‘Not so that anyone would notice,’ I said.

Red smiled at me but when she learned that two one-time champions were about to fight out a match in the next room she took my hand and dragged me along there.

Backgammon is more to my taste than chess. The dice add a large element of luck to every game, so that sometimes a novice beats a champion just as it goes in real life. Sometimes, however, a preponderance of luck makes a game boring to watch. This one was that – or perhaps I was just feeling bad about the way Red exchanged smiles and greetings with so many people round the table.

The two ex-champions were into the opening moves of their third game by the time that Bessie Mann plucked my sleeve to tell me that her husband wanted me.

I went down the hall to where Tony Nowak’s driver was standing on guard outside the bedroom. He was scowling at the mirror and trying to look like a cop. I was expecting the scowl but not the quick rub down for firearms. I went inside. In spite of the dim lighting, I saw Tony Nowak perched on the dressing-table, his tie loosened and his brow shiny.

There was a smell of expensive cigars and after-shave lotion. And seated in the best chair – his sneakers resting upon an embroidered footstool – there was Harvey Kane Greenwood. They had long ceased to refer to him as the up-and-coming young Senator: Greenwood had arrived. The long hair – hot-combed and tinted – the chinos and the batik shirt, open far enough to reveal the medallion on a gold neck-chain, were all part of the well-publicized image, and many of his aspirations could be recognized in Gerry Hart, the lean young assistant that he had recently engaged to help him with his work on the Scientific Development Sub-Committee of the Senate Committee of International Cooperation.

As my eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, I saw as far as the Hepplewhite sofa, upon which sat two balding heavyweights, comparing wrist-watches, and arguing quietly in Russian. They didn’t notice me, and nor did Gerry Hart, who was drawing diagrams on a dinner napkin for his boss Greenwood, who was nodding.

I was only as far as the doorway, when Mann waved his hands, and had me backing-up past Nowak’s sentry, and all the way along the corridor as far as the kitchen.

Piled up along the working surfaces there were plates of left-over party food, dirty ashtrays and plastic containers crammed with used cutlery. The remains of two turkeys were propped up on the open door of a wall oven, and as we entered, a cat jumped from there to the floor. Otherwise the brightly lit kitchen was unoccupied.

Major Mann opened the refrigerator and took a carton of buttermilk. He reached for tumblers from the shelf above and poured two glassfuls.

‘You like buttermilk?’

‘Not much,’ I said.

He drank some of it and then tore a piece of paper from a kitchen-roll and wiped his mouth. All the while he held the refrigerator door wide open. Soon the compressor started to throb. This sound, combined with the interference of the fluorescent lights above our heads, gave us a little protection against even the most sophisticated bugging devices. ‘This is a lulu,’ said Mann quietly.

‘In that case,’ I said, ‘I will have some buttermilk.’

‘Do we want to take delivery of Mrs B?’ He did not conceal his anger.

‘Where?’ I asked.

‘Here!’ said Mann indignantly. ‘Right here in schlockville.’

I smiled. ‘And this is an offer from gentleman-Jim Greenwood and our friend Hart?’

‘And the two vodka salesmen from downtown Omsk.’

‘KGB?’

‘Big-ass pants, steel-tipped shoes, fifty-dollar manicures and big Cuban cigars – yes, my suspicions run that way.’

‘Perhaps Hart got them through central casting.’

Mann shook his head. ‘Heavy,’ he said. ‘I’ve been close to them. These two are really heavy.’

Mann had the mannerism of placing a hand over his heart, the thumb and forefinger fidgeting with his shirt-collar. He did it now. It was as if he was taking an oath about the two Russians.

‘But why?’

‘Good question,’ said Mann. ‘When Greenwood’s goddamned committee is working so hard to give away all America’s scientific secrets to any foreigner who wants them – who needs the KGB?’

‘And they talked about B.?’

‘I must be getting senile or something,’ said Mann. ‘Why didn’t I think about those bastards on that Scientific Cooperation Committee – commie bastards the lot of them if you ask me.’

‘But what are they after?’

Mann threw a hand into the air, and caught it, fingers splayed. ‘Those guys – Greenwood and his sidekick – are lecturing me about freedom. Telling me that I’m just about to lead some kind of witch-hunt through the academic world …’

‘And are we?’

‘I’m sure going to sift through Bekuv’s friends and acquaintances … and not Greenwood and all his pinko committeemen will stop me.’

‘They didn’t set up this meeting just to tell you not to start a witch-hunt,’ I said.

‘They can do our job better than we can,’ said Mann bitterly. ‘They say they can get Bekuv’s wife out of the USSR by playing footsie with the Kremlin.’

‘You mean they will get her a legal exit permit, providing we don’t dig out anything that will embarrass the committee.’

‘Right,’ said Mann. ‘Have some more buttermilk.’ He poured some without waiting to ask if I wanted it.

‘After all,’ I said in an attempt to mollify his rage. ‘It’s what we want … I mean … Mrs B. It would make our task easier.’

‘Just the break we’ve been waiting for,’ said Mann sarcastically. ‘Do you know, they really expected us to bring Bekuv here tonight. They are threatening to demand his appearance before the committee.’

‘Why?’

‘To make sure he came to the West of his own free will. How do you like that?’

‘I don’t like it very much,’ I said. ‘His photo in the Daily News, reporters pushing microphones into his mouth. The Russians would feel bound to respond to that. It could get very rough.’

Mann pulled a face and reached for the wall telephone extension. He capped the phone and listened for a moment to be sure the line was not in use. To me he said, ‘I’m going back in there, to tug my forelock for ten minutes.’ He dialled the number of the CIA garage on 82nd Street. ‘Mann here. Send my number two car for back-up. I’m still at the same place.’ He hung up. ‘You get downstairs,’ he told me. ‘You go down and wait for the back-up car. Tell Charlie to tail the two Russian goons and give him the descriptions.’

‘It won’t be easy,’ I warned. ‘They are sure to be prepared for that.’

‘Either way it will be interesting to see how they react.’ Mann slammed the refrigerator door. The conversation was ended. I gave him a solemn salute, and went along the hall to get my coat.

Red Bancroft was there too: climbing into a fine military-styled suede coat, with leather facings and brass buttons and buckles. She winked as she tucked her long auburn hair into a crazy little knitted hat. ‘And here he is,’ she said to the intruder alarm manufacturer, who was watching himself in a mirror while a servant pulled at the collar of his camel-hair coat. He touched his moustache and nodded approval.

He was a tall wiry man, with hair that was greying the way it only does for tycoons and film stars.

‘The little lady was looking everywhere for you,’ said the intruder alarm man. ‘I was trying to persuade her to ride up to Sixtieth Street with me.’

‘I’ll look after her,’ I said.

‘And I’ll say good night,’ he said. ‘It was a real pleasure playing against you, Miss Bancroft. I just hope you’ll give me a chance to get even sometime.’

Red Bancroft smiled and nodded, and then she smiled at me.

‘Now let’s get out of here,’ I whispered.

She gripped my arm, and just as the man looked back at us, kissed my cheek. Whether it was nice timing, or just impulse, was too early to say but I took the opportunity to hold her tight and kiss her back. Tony Nowak’s domestic servants found something needing their attention in the lounge.

‘Have you been drinking buttermilk?’ said Red.

It was a long time before we got out to the landing. The intruder alarm man was still there, fuming about the non-arrival of the elevator. It arrived almost at the same moment that we did.

‘Everything goes right for those in love,’ said the alarm man. I warmed to him.

‘You have a car?’ he asked. He bowed us into the elevator ahead of him.

‘We do,’ I said. He pressed the button for ground level and the numbers began to flicker.

‘This is no city for moonlight walks,’ he told me. ‘Not even here in Park Avenue.’

We stopped and the elevator doors opened.

Like so many scenes of mortal danger, each constituent part of this one was very still. I saw everything, and yet my brain took some time to relate the elements in any meaningful way.

The entrance hall of the apartment block was brightly lit by indirect strip-lighting set into the ceiling. A huge vaseful of plastic flowers trembled from the vibration of some subterranean furnace, and a draught of cold wind from the glass entrance door carried with it a few errant flakes of snow. The dark brown floor carpet, chosen perhaps to hide dirty footmarks from the street, now revealed caked snow that had fallen from visitors’ shoes.

The entrance hall was not empty. There were three men there, all wearing the sort of dark raincoats and peaked hats that are worn by uniformed drivers. One of them had his foot jammed into the plate-glass door at the entrance. He had his back to us and was looking towards the street. The nearest man was opposite the doors of the elevator. He had a big S & W Heavy-Duty .38 in his fist, and it was pointing at us.

‘Freeze,’ he said. ‘Freeze, and nobody gets hurt. Slow now! Bring out your bill-fold.’

We froze. We froze so still that the elevator doors began to close on us. The man with the gun stamped a large boot into the door slot, and motioned us to step out. I stepped forward carefully keeping my hands raised and in sight.