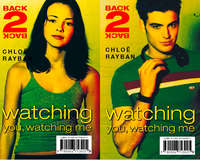

Watching You, Watching Me

BACK 2 BACK

watching

you, watching me

Tasha’s side of the story …

CHLOË RAYBAN

with grateful thanks to James Ross, Felix Milton, Molly Milton and Leo Bear for their help with the music and club scene

CONTENTS

Cover

Book One Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Also by Chloë Rayban

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

There it was again. That creepy feeling in the small of my back. I swung round and looked back down the road. I could feel someone watching me. But where from? The street was deserted, not even a car coming down it. I scanned windows for twitching nets, and my gaze settled on number twenty-five.

Number twenty-five had been boarded up for ages, years. Ever since Mr Copps, the old man who’d lived there, had died. There’d been some sort of legal battle about who was meant to inherit it, and until this was settled it couldn’t be sold.

Jamie and Gemma called it ‘the spook house’, and I must admit that on occasions, when they were being a real pain while I was baby-sitting, I’d made up ghost stories about it to keep them quiet. Jamie had woken up screaming with a nightmare one night, so Mum had put an end to that. She was livid.

Number twenty-five looked pretty spooky, as a matter of fact, on an overcast afternoon like today. It was a tall terraced house like the others in the street, but the windows, with their rough covering of weathered boarding, gave it a blind, desolate look. Paint was peeling off the window frames and weeds had grown up through the front path. There was a row of house-martins’ nests under the eaves — slowly nature was taking over.

I shook myself and continued down the road. I decided to put the whole thing down to an over-active imagination. My own fault really for making up all those stories.

It was later that evening, when he was meant to be getting ready for bed and was hiding from Mum behind the curtains in my room, that Jamie suddenly let out a whimper.

‘Tasha!’ He ran and clung to me.

‘Hey … what is it?’

They’re there … they’re really there …’

‘Who are where?’

‘At number twenty-five — the spooks’

‘Don’t be silly. ‘Course they’re not. No such thing as spooks. You know that, don’t you?’

‘But there are. They’re there …’ He dragged at my sleeve. ‘Come ‘n look … There’s lights moving around in the house.’

‘Rubbish,’ I said. But I could feel the little hairs on the back of my neck rising in spite of myself. ‘You’re making it up.’

‘No honest … There are … Look.’

I let him lead me to the window, and we crouched in the dark part between the curtains and the windowpane, staring out.

‘Where?’ I demanded. This was typical of Jamie, always blowing up the most trivial thing into a drama.

‘Wait …’ he whispered. His hand was holding my arm so hard it hurt.

I scanned the bleak façade of number twenty-five. And then I froze. He was right. Just the faintest glimmer of a light, but it was moving through the rooms. You caught a glimpse of it every time it passed a crack in the boarding. It would pause and glimmer and then it would flicker on. It was moving up now as if something was floating upwards through the house …

‘What are you two up to?’ Mum pulled the curtains back and found us sitting there.

‘We’ve found a spook,’ said Jamie, now emboldened by the presence of Mum and the cheery light of the room.

‘Tasha …’ said Mum with a warning look.

‘No … its not me this time, honestly. But there is someone or something in number twenty-five … See for yourself.’

The three of us huddled behind the curtain. It took some minutes before Mums eyes became accustomed to the gloom, and then she pronounced:

‘Squatters.’

‘What’s squatters?’ asked Jamie, his lower lip wobbling. To his six-year-old brain ‘Squatters’ were quite possibly as bad as spooks, or maybe they were worse — a special kind of spook, one that moved around by a kind of legless elevation like those weirdo yogic flyers.

‘That’s the limit,’ she said. ‘I knew something like this would happen if that house was left empty like that.’ She set off down the stairs to find Dad.

‘Tasha — what are squatters?’ demanded Jamie again in a wavering voice.

I put an arm round him. ‘Squatters are people who haven’t got homes of their own. So they find empty houses and they break in and squat in them.’

‘Why can’t they stand up straight?’

‘They can, silly … ‘Squat’ is just a word that means … umm … to take over an empty house and live there, without paying rent or anything.’

‘Why isn’t there a proper word?’

‘I don’t know!’ I hadn’t time to get into ‘why-mode’ for a discussion with Jamie — I wanted to know what Dad was going to make of the situation.

Dad came striding through my door at that moment. He stuck his head through the curtains and stared out.

‘Can’t see a thing — you’re all making this up.’

‘Wait until your eyes get adjusted,’ said Mum.

‘Hrrmph,’ said Dad.

‘It’s not spooks, it’s ‘squatters’,’ said Jamie importantly. They’re people who haven’t got houses so they go and live in other people’s houses while they’re out …’

‘I know what ‘squatters’ are, thank you Jamie … shhh!’ He waved a hand behind him for silence. I joined him, and we stood together for a moment straining our eyes towards the shadowy house.

‘See … There it is in the top room,’ I said.

‘Yeaahhh,’ said Dad. ‘Flickering … must be a candle …’

‘Right. I’m going to phone the police,’ said Mum.

‘No hang on …’ said Dad. He extricated himself from the curtains. ‘Let’s think about this for a moment.’

‘What’s there to think about?’

‘Well … How long has that house stood empty?’

‘Two years … could be three.’

‘So that’s two or three years when the house could have provided a roof over someone’s head. Some poor individual who’s been sleeping rough in a doorway or something.’

I loved the way Dad was like this — always surprising me — always ready to see the other side of the question. I slipped an arm through his.

‘Dad’s right. Mum. There could be some poor homeless person in there, trying to shelter.’

‘Poor homeless person! Next thing we know there’ll rubbish all the way up the street, rats, needles — God knows what else …’

‘It’s a situation this country’s brought upon itself,’ said Dad.

‘This is a respectable street. Families, children … the last thing we need is squatters.’

At that point Jamie upset my entire carefully-stacked collection of CDs. This mini-landslide brought Mum’s attention back to him and she remembered the initial reason for coming into my room.

‘Bed for you Jamie. Goodness, look at the time!’

She went off with him, still grumbling over her shoulder at my father.

‘You and your oh-so-liberal views.’

‘You may or may not have forgotten … I lived in a squat myself once,’ Dad called after her.

‘You? You were a squatter?’ I exclaimed.

‘Not for long. When I was a student. We were so hard up we had no choice. But we got the place running like clockwork. I reckon we did the people who owned it a favour. Damp old house it was before we cleaned it up. Mended the roof too — all the ceilings would have been down in another few months.’

‘So what do you think we should do?’

‘I reckon I ought to pay our new neighbours a visit. See if they’ve got forked tongues and fangs …’

‘What if they have?’

‘You willing to stand watch?’

‘Sure …’

‘Bring the portable in here and if you see someone coming at me with a meat cleaver — ring 999 straight away. Oh … and … Don’t tell Mum, OK?’

I stood at the window grasping the portable really tightly. I had a sick feeling in my throat. What if there were violent people in there — criminals — thugs?

I watched Dad cross the road and make his way up the overgrown front path. He hammered on the front door. The sound echoed down the road. I wondered if Mum would hear, but by the sound of bathwater running, I could tell she was busy bathing Jamie.

Nothing happened for a while. Then Dad hammered again, harder this time. Number twenty-five seemed absolutely silent — uninhabited. And then, I tightened my hold on the portable. The light on the first floor was on the move again, floating and glimmering through chinks in the boarding. It was descending through the house.

I waited tensely, expecting the front door to be split asunder any minute and some equivalent of the Incredible Hulk to come bursting through. But it didn’t. Dad just stood there. He seemed to be talking animatedly through the door, waving his arms around. I could tell by his back that he was speaking but I couldn’t catch what he said because Mum was letting the bathwater out. Then Dad seemed to give up — he shook his head and came back across the road.

I heard our front door slam.

I headed down the stairs.

‘What happened? What did they say?’

Dad cleared his throat. ‘Bloody confident little bastard, whoever he is. Said he had every right to be there. Told me I was an interfering old busy-body. And suggested that I … Piss off.’

I could tell by Dad’s tone that he felt put-down. Guess it was a male pride thing — he’d gone over that road in the spirit of a well-wisher, a comrade-in-arms, and he’d been told to get lost. I managed to stifle the impulse to giggle. He went to the fridge and took out a can of lager, snapped it open and sat down, thoughtfully sipping it.

‘What did he sound like — this bloke? A great big bruiser?’

‘No … not at all. Quite young …’

‘How young?’

‘Hard to tell but couldn’t be more than, say seventeen … eighteen?’

‘Who?’ Gemma had left off watching the TV and was helping herself to juice from the fridge.

‘Someone who seems to have moved in over the road, number twenty-five.’

‘What, in the spook house?’

‘It’s not a spook house, remember. No such things as spooks. Gemma,’ said Dad, taking the juice container out of her hand and returning it to the fridge before she drank the lot.

‘Seventeen or eighteen. What does he look like?’ asked Gemma. Already I could see she was assessing his romantic potential. Gemma was positively addicted to romances. Love Stories, Sweet Valley High, Mills & Boon — Gemma consumed all this stuff at the rate of three books a week.

‘I haven’t actually seen him yet. We talked through the door.’

‘Oh … but you must be able to tell. You can from voices, you know. I read this book about these two people who fell in love over the telephone. They’d never even met and it was the real thing …’

‘Gemma listen,’ I said. This is like some tramp or something. Wild-eyed, unshaven, overweight maybe. He probably smells … Really rough.’

‘He didn’t sound rough. Just annoyed,’ said Dad. ‘Funny business.’

We could hear Mum coming downstairs. Dad obviously wanted to bring the discussion to a close.

‘Hey Gem. Your bedtime. Off you go.’

‘Must I?’

Mum appeared at the kitchen door. ‘Yes, you must. Term starts tomorrow, remember?’

Later that night, when I went up to bed, I opened my window as usual. Dad has this real thing about fresh air. Unless its about ten degrees below, he absolutely insists we sleep with the windows open. He says we can pile on as many duvets as we like but young lungs need fresh air and the air is freshest at night when there’s not so much traffic around. He’s got this big thing about traffic too, but I won’t bore you with all that right now. I stared out of the window. The light was still there, flickering in the top room now. With the curtains drawn around behind me, I settled down to watch. Nothing much was happening — only the light was moving around a bit. And it was pretty chilly too.

‘What’s going on?’ Gemma’s small warm body thrust itself against mine.

‘Ssssh!’ I said unnecessarily, as he could hardly have heard us from across the street. ‘Nothing.’

‘I reckon he looks like Liam Gallagher. Unshaven, you know, and kind of hungry-looking. Dead sexy.’

‘What would you know about it?’ Gemma was only nine.

‘What would you?’ she retorted. You’ve never even had a boyfriend.’

She was right really. At fourteen I didn’t score too highly on the ‘boyfriend’ front. Unless you counted being kissed at Christmas by Stephen, my cousin, but he was a total dweeb and since it was under the mistletoe, I guess it didn’t count anyway. Girls at school had been going out with guys since they were twelve practically. I was teased about my single status the whole time. But short of bumping into the boy of my dreams in the local shopping mall, I didn’t have that much opportunity for male conquest. Mum and Dad were dead strict about pubs and clubs, and even parties were vetted. It really wasn’t fair.

‘Look, it’s gone out,’ said Gemma. The light had suddenly been extinguished. We sat in silence for a few minutes more. Watching a flickering candle was pretty boring, but watching a totally dark house was ridiculous. So we went to bed after that.

I lay in bed unable to sleep for hours. My mind kept on making up different photo-fits of our mysterious new neighbour.

I had just got to Mystery-Man Photo-Fit Number Eight which was a bronzed kind of Baywatch guy who’d escaped from Hollywood and come to Britain because he was being hounded by Interpol for a murder he hadn’t committed and was trying to clear his name. I featured prominently in this one, working as an undercover agent and doing amazingly heroic acts for which he was stunned and grateful and he was just about to …

When I must have fallen asleep.

Chapter Two

Mornings in our house are always pretty unbelievable. But the first morning of any term gets the chaos award.

I left as much time as I reasonably could before I made my appearance downstairs. Mum had called six times. I climbed into my loathsome uniform. Grey skirt made as short as I dare by rolling round the waistband (a quick unroll adds that vital inch on uniform inspection days). Hideous white shirt you can see your bra through, yukk! I’d forgotten the gross feel of the nylony fabric — the kind of stuff that gives off electric shocks like forked lightning when you undress in the dark. Dangerous if you ask me. Tie — now I reckon it’s kinky making girls wear ties. And to complete the ensemble, scratchy nylon and acrylic mix grey cardie — ghastly!

I stomped downstairs. Gemma was sitting on the third step practising her recorder. The ‘tune’ she was attempting to master was ‘London’s Burning’. Every time she got to the two final notes — ‘Fire, Fire’ — she played two painfully wrong ones.

‘Shut up Gems — you’re giving everyone a headache!’

‘Miss Dawson said we had to have it perfect over the holidays.’

‘But you’ve had all summer!’

I climbed over her. Mum was dressed in her smart ‘I’ve got a meeting at work’ outfit and making sandwiches distractedly.

‘Oh, there you are. You couldn’t be an angel and find Jamie’s football gear for me, could you? It’s brand new, should be in the drawer but …’

‘He’s been wearing it as pyjamas,’ chimed in Gemma, appearing in the kitchen doorway.

‘I have not …’ said Jamie going red — and an argument broke out.

Mum tore open a tin of tuna and Yin and Yang started up a chorus at her feet.

‘Jamie, its your job to feed the cats this week. Why aren’t they fed?’

‘Mum!!!!! …’ Gemma was staring at the sandwiches practically in tears. You know I can’t stand mayonnaise. It makes me want to throw up. The very sight of it and I puke …’

‘Oh goodness yes … I forgot. OK … Tasha, you feed the cats and Jamie, you get your football gear.’

‘Dad came in. I couldn’t find them. Definitely not in the bedroom.’

‘What?’

‘The car keys.’

‘I don’t believe this! We’re going to be late,’ Mum fussed.

Gemma broke off in the middle of an ear-piercing wrong note. ‘Mu-um, we can’t be late on the first day. I’ll get a seat near the front …’

‘I’ll look for the keys,’ I offered — anything to avoid smelly cat food duty.

‘Hey Gems … its OK, your sandwich hasn’t got mayonnaise on now,’ said Jamie.

Mum leapt at Yang, who in the absence of breakfast, had seized his opportunity and was licking mayonnaise off Gemma’s bread.

‘If you smack him I shall ring the NSPCC,’ said Gemma.

‘Try the RSPCA, Gemma,’ suggested Dad. ‘Unless you continue playing that thing — then we might need both.’ And with that he scooped up his briefcase and escaped through the front door.

Mum headed upstairs.

Gemma poured milk on her cereal.

‘I wonder if he’s got any breakfast over there …’ she sighed to me.

‘Who?’ asked Jamie as he spooned cat food ever so slowly and carefully on to two saucers. Yin and Yang were practically going berserk at his feet.

I shoved the saucers under their noses.

‘Maybe we should make up a food parcel, like in a basket or something, and then he could let down a rope and haul it up to his room,’ continued Gemma in a dreamy tone.

‘Dad’s trying to get rid of him, not encourage him,’ I pointed out.

‘But what if he stays up there and starves to death? It’ll be our fault.’

‘He could have my tuna sandwiches and then I’d have to have school dinners,’ suggested Jamie generously. Mum didn’t approve of school dinners. She reckoned they served factory-farmed meat, and they had chips too which she insisted were really unhealthy. Jamie went positively dewy-eyed over the very thought of a school dinner.

‘Shall I make some toast for him?’

‘No, Gemma. Absolutely not.’

The last thing we needed was Gemma doing something typically cringe-worthy like sending over food parcels. Having her act of charity rejected, she returned crossly to the stairs and started up her recorder torture again.

Mum came down the stairs like a whirlwind, holding out Jamie’s football gear.

‘Gemma was right! They were in your bed.’

‘You’ve got a ladder in your tights, Mum. A really humungous one,’ remarked Gemma.

‘I haven’t! I have! The keys! Tasha we’re going to be so late!’

We were late. I found Mum’s keys in the fridge. I reckon Dad must have picked them up last night when he’d had the set-to with the ‘squatter’ and then shoved them in there when he’d got the beer. He’d been in a bit of a state.

So we all piled in the car, and just as Mum was trying to persuade it to start … this boy came out of number twenty-five. He shot through the gate that led round to the back garden, bold as brass as if he owned the place. He was really fit actually. I craned out of the back to get a better view.

‘Cor …’ said Gemma.

‘Gems, that is a really vile and vulgar expression,’ I said, signalling violently to her not to draw Mum’s attention to our new neighbour. Mum hadn’t seen him — she’d been too busy battling between the ignition and the choke. I prayed she wouldn’t realize where he’d come from. For all I knew, she’d be out of that car in a flash and doing a citizen’s arrest on him or something.

The car started at last and Mum coaxed it out into the street. He was ahead of us now, sashaying along on rollerblades, dead in the middle of the road, making it impossible for Mum to pass.

‘I don’t believe this!’ she muttered, really losing her cool. She hooted at him but he didn’t take a blind bit of notice. This guy had some cheek.

But Gemma was right — he was well ‘Cor!’ I mean, guys always look good on rollerblades — gives them extra height and all that. But apart from the nice build which I’d noticed as he came out, he had a really OK face too. He wasn’t unshaven as a matter of fact — he was pretty tanned as if he’d just come back from holiday and his hair was kind of rough and sun-bleached. I mean, he was about the best thing I’d ever seen down our street. Squatter or not — he was good news.

A milk float lurched round the corner and approached us. Now any chance of passing him was totally out of the question.

Mum put her hand down on the hooter again.

‘This young man is going to get himself killed if he’s not careful!’

She hooted again and waved wildly at the milkman. The milkman got her drift and went all officious, flagging him down as if he were a policeman. Our rollerblader suddenly came to an abrupt stop, and Mum nearly collided with him. The guy shot a glance over his shoulder and did an ace wobble and double-take, nearly landing on his backside. You should have seen his face!

‘Just what do you think you’re doing!’ Mum yelled at him. She always gets hysterical when she sees someone endangering themselves.

The guy recovered himself and took the two little foam Walkman speakers out of his ears. I could hear the jangle of the bass from inside the car. He must have had it on full blast. No wonder he hadn’t heard the car. The idiot! He stood there looking foolish for a moment. And then he caught sight of me in the back of the car. I was killing myself — silently, so as not to enrage Mum even more. He frowned, obviously realising what a total prat he’d made of himself.

‘Look — do you know the way to West Thames College?’ he asked.

‘I know the way to West London Cemetery — and that’s where you’re heading at this precise moment,’ said Mum.

‘Sorry but — you must’ve come from nowhere!’ he said.

Mum pointed at the head-set. ‘If you want to stay alive, I’d give that a rest if I were you.’

‘Yeah, well maybe …’

‘If I see you doing that again, I won’t be so lenient. I’ll run you over,’ she added.

‘Feel free … Mind how you go now,’ he said. And he waved her on with a flourish.

‘Hmmmph — he’s got a cheek,’ said Mum, but she kind of smiled to herself all the same. Then she thrust the gear lever into second gear and concentrated on getting us through the traffic to school.

OK — school. That first day back is never as bad as you think it’s going to be. You arrive there all ready to muster your reluctant brain-cells and force them back to work, then most of the day turns out to be timetable-planning and book lists and general reorganisation. All of this was carried out by harrassed teachers who were fighting a losing battle against our real purpose of the day — to find out what everyone else did on holiday and go one better.