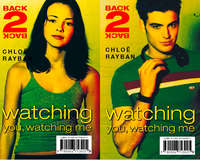

Watching You, Watching Me

‘But it’s what he’s drinking …’ said Mum.

I could resist no longer. I joined Mum and Jamie and stared out as well.

Sitting on the wall outside number twenty-five, there was this boy with his hair shaved round the sides and cut in a sort of slab on top. He was taking swigs out of a bottle — a Smirnoff vodka bottle.

‘What did I tell you?’ said Mum. ‘Let squatters into the street and there’ll be nothing but trouble. I should call the police.’

‘No!’ I said. You can’t do that. He’s probably nothing to do with the house. I expect he’ll move on in a moment.’

This statement was immediately contradicted by the window two storeys above opening. A figure leaned out. It was him.

‘Come on up. I’ve found something better up here.’

I left the window in a hurry and went and sat on the sofa well out of sight.

Mum glared at me. ‘See?’

‘No, I don’t see,’ I said. You’re jumping to conclusions.’

Mum continued peering out of the upper window. ‘Look upstairs. It’s that boy from the other morning. The one I nearly ran down rollerblading. The one who had such a cheek.’

‘Oh … is it?’ I asked, trying not to sound in the least bit interested.

‘He’s our squatter,’ said Gemma, giving me a nudge. ‘Come away, It’s not fair on Tasha to stare at him like that.’

‘What’s going on?’ demanded Mum.

‘Tasha really fancies him,’ said Jamie in a matter-of-fact voice.

Gemma nudged Jamie hard.

‘I do not!’ I said hotly.

‘That would be just so typical!’ said Mum. ‘A girl with no problems whatsoever. Doing well at school. And then someone like that moves into her street and …!’ She paused, peering out again. ‘Oh that’s too much.’

‘So what’s going on now?’ I asked.

‘He’s smoking a big fat cigarette,’ said Jamie.

‘Stay well away from them. That’s all I’m going to say,’ said Mum. She started vacuuming again in a haphazard way with one eye on the window.

Mum thinks she knows it all. She’s got this part-time job as an educational psychologist. She’s used to seeing kids that have gone off the rails. She spends her whole time sorting out disputes, counselling people who’ve been expelled and helping to fix up places in special schools. I reckon it makes her over-react sometimes.

‘I’m going upstairs where I can get some peace to finish my French,’ I said.

I settled down lying on my stomach on my bed facing the window. My room was in shadow so I knew no-one could see in. The guy with the flat-top haircut was leaning out of the attic window opposite, smoking now. And it didn’t look like an ordinary cigarette. He still had the vodka bottle in his hand. He looked down and waved it in the direction of our living room. He must have caught sight of Mum watching him.

The two boys appeared to be fooling around the ways boys do when they think they have an audience. I could have killed Mum. She must be staring out through the window. And they were certainly making the most of it.

The boy waved the bottle again. It was nearly empty now. How on earth could squatters afford to drink vodka like that? That’s if it was vodka, of course. I was starting to have my doubts. The way the boys were fooling around didn’t look totally convincing to me. The chap with the flat-top haircut was really camping it up. He stood at the window and made his eyes go completely crossed and then fell over flat, backwards. I was killing myself.

Mum must’ve been going ballistic down below.

The falling-over act seemed to conclude the show. They’d disappeared from sight. I wondered what it was like being a squatter. What did they live on? Social Security? Was the house filthy and vermin-infested like Mum said? If I lived in a squat I’d make the place exactly how I wanted it. I’d paint the walls black or silver maybe. Perhaps I’d paint murals all over them — and I’d find things in skips and do them up. It must be absolutely fantastic being able to do exactly what you want with no parents around. Being able to stay in bed as long as you want, for instance — eat what and when you like — play music as loud as you like — go out wherever and however late you like.

My parents are really repressive. I reckon it has a lot to do with the fact I’m the eldest. I haven’t had someone up ahead of me to kind of break them in — establish the ground rules. They’re always easier on Gemma — she can do things I was never allowed to do at the same age. By the time Jamie’s my age they’ll probably have given up rules entirely. It’s so unfair!

The boys didn’t reappear. I rolled over on my back and stared at the ceiling. Out of all the girls in my class I reckon my parents are the strictest. Maybe some of it’s boasting, but from what I’ve heard, other girls my age are allowed to go out loads more than me. They dress up and get into pubs and clubs. My parents would have a fit if I did any of those things. They still think I’m a child.

I sat up and stared at my reflection in the bedroom mirror. I even look young for my age. I didn’t stand a chance with a guy like the one over the road. He’d hardly want to be seen around with some kid.

You know what Mum says? It’s the most depressing and infuriating thing anyone can say: ‘Your turn will come, Natasha.’ Well, I simply don’t believe it. By the time it’s my turn, it’ll be too late.

I lay there for quite a while trying to summon up the energy to finish my French homework. I strained my ears for sounds from the house opposite but I guess the boys must have gone out or something.

It was a warm evening and my window was open. I could hear the anxious cheeping and scrabbling of the house-martins. They made a rough mud nest under the eaves of our house every year. This one was just above my bedroom window. Gemma was doing a nature project on them for school and was always barging into my room to check on them. It had been a bit of a pain to start with, but then I couldn’t help getting involved. This summer the parents had brought up three separate broods of fledglings. So there had been constant comings and goings as the parents tried to keep up with their demand for food. I could see a couple of martins darting back and forth across the street catching insects right now. I loved the way they always looked so neatly dressed in black and white — like an anxious pair of waiters in a smart restaurant, with a load of diners grumbling about the time they took bringing the food. And it wasn’t just the adults who did the work. Later in the year — like right now — the earlier, older fledglings would join in and help feed the younger ones. You’d think they’d prefer to be off on their own somewhere, wouldn’t you? Flying down to Spain perhaps, sorting out where they were going to spend the winter? Instead, they were stuck at home doing chores for Mum and Dad. I’d started to identify with some of those martins over the course of that project.

Gemma had wandered into my room.

‘Hi,’ she said, sitting down on my bed beside me.

‘What’s up? Nothing on TV?’

‘Just wondered what was going on over there.’ She indicated the window over the road.

‘Absolutely nothing.’

‘Oh. Sorry about letting on to Mum.’

‘I’ll survive.’

‘But you do fancy him, don’t you?’

‘He’s all right.’

She leaned towards me and asked in an undertone: ‘Do your knees go to Jell-o whenever you see him?’

‘Go to what?’

‘Jell-o.’ She paused. ‘What is Jell-o?’

‘Jell-o is American for jelly. And no, they don’t as a matter of fact. Honestly, Gem. I don’t know what you see in those books.’

Chapter Six

The school week dragged to an end at last, and Friday found me in my room doing my long overdue oboe practice.

I had a really difficult piece to practise for my next exam. It had this long sustained opening note which you had to count through and keep your breathing controlled until you felt you could burst. I dread to think what I must have looked like while playing it.

On my third attempt it really came out well. The piece was by Albinoni. He’s a genius. If you play his music properly it’s really stunningly beautiful. That’s the funny thing about practice. You put it off and put it off and when you can’t put it off any longer and it comes to doing it — you find you enjoy it. No, not just enjoy It’s as if you’re on another plane when you really get into it. You get to a state when you’re so totally absorbed that you can’t break off …

Like now.

‘Natasha, can you hear me?’

‘Yes Mum … What is it?’

‘Help me with this, can’t you?’ Mum’s voice was muffled. She appeared in her bedroom doorway half-in and half-out of a dress, her best dress.

I put down the oboe and went to rescue her. I gave the dress a tug and her head appeared over the top.

‘Can you keep an eye on Jamie and Gemma? It’s only for a few hours. I’ll be back by 9.30.’

‘But it’s Friday …’

‘Yes, and this is a very important meeting. Might mean promotion.’

‘I’m doing my oboe practice.’

‘Well, that won’t take all night.’

‘Why can’t Dad babysit?’

‘Working late on that river project.’

‘Uggghh.’

‘You can take the two of them to the cinema, my treat.’

‘Big deal. We can go to a U.’

Mum was leaning into her three-piece mirror putting lipstick on. I stood behind her and watched critically.

‘You ought to use a lipliner you know — you’d get a much better shape.’

‘You said yourself you wanted to see Babe,’ she mumbled, rubbing her lips together. They’re doing a rerun at the MGM.’

I had actually. OK, I know it’s pathetic, but I still get a kick out of kids’ films — it’s the one and only compensation for having a younger brother and sister. You can veg out in front of stuff like 101 Dalmatians and pretend it’s for their benefit.

‘Popcorn and ice-cream too?’

Mum put a tenner on the dressing table and then increased the bribe by adding a five pound note.

‘It’s a deal then,’ I said sweeping them up. What time does it start?’

‘You’ve missed the early performance — have to take them to the 7.15. So you can finish your practice first.’

‘Can I stand the pace?’

Mum straightened up and took an assessing look at herself in her full-length wardrobe mirror.

‘How do I look?’

I’ve never liked the dress. It’s a really ghastly oxblood red and that terrible middle aged length that makes you look as if you end at mid-calf.

‘It’s not exactly power dressing, is it?’

‘What do you think I should wear?’

‘Your black suit.’

‘The skirt’s too short.’

‘Rubbish. You’ve got good legs Mum, flaunt them. And you need mascara too.’

It took about half an hour to get Mum looking halfway decent, and I had to lend her my lip-gloss. She took another long assessing look at herself in the mirror.

‘I look like Joan Collins.’

‘Well look how successful she is.’

‘True. And — oh my God! Look at the time! I’ve got to dash. They’ve both had tea. Now make sure Jamie holds your hand anywhere near a road. And …’

‘Mum … Do you think I’m stupid or what?’

‘Or what,’ she said, giving me a hasty kiss.

‘Thanks. Knock ‘em dead.’

‘Do you really think I look OK?’

‘Of course!’

‘Not mutton dressed as lamb?’

‘You looked like lamb dressed as mutton in that red thing. Raw mutton.’

‘OK … Here goes.’

We could walk to the MGM from our house. Jamie and Gemma kept running on ahead so I was forced to run with them. Going with me instead of Mum made it an extra-special treat, and I knew that it was going to be a struggle to stop them getting out of hand.

We arrived at the cinema hot and out of breath to find there was a queue and it had started to drizzle too. We’d hardly joined the tail-end before Jamie started to put the pressure on for me to go inside and stock up with supplies of popcorn.

‘It’s raining,’ I pointed out. ‘It’ll only get soggy. Wait till we’re inside.’

The queue was moving really slowly and there were at least forty people ahead of us. My hair had started sticking to my head in a most unflattering fashion. That’s when Gemma nudged me hard.

‘Look,’ she said.

It was him. He was walking down the road with this incredible girl. She had really high-heeled boots on and a minimal skirt topped by a black leather jacket. And she was walking with him as if she owned him.

They joined the queue opposite ours — the one for White Knuckle, a really tough suspense movie just released. The one I’d been planning to see with Rosie until tonight’s alternative entertainment cropped up.

Gemma looked at me balefully. I ignored her. The last thing I needed was her sympathy. ‘She could be his sister,’ she whispered.

Out of the corner of my eye I could see that the girl had started practically rubbing her body against his. Some sister. Get any closer and she’d be inside his jacket. She kept pulling at his sleeve to get eye contact.

‘Huh,’ I said. All I was interested in at that point was getting into the cinema without being noticed.

But as luck would have it, their queue and our queue coincided at the MGM doors at precisely the same moment.

‘Hi …’ I heard him say.

‘Hello …’ said Gemma.

I vaguely murmured a cross between the two that came out like a painful hybrid ‘Hi-lo”. Hoping that if I didn’t look at him, he wouldn’t look at me, I gazed at the pavement which was dotted with blobs of discarded chewing-gum — riveting.

‘Are you going to see Babe?’ I heard Jamie ask. (Thanks Jamie.)

‘No, as a matter of fact, but I’ve heard it’s good …’ he was saying.

There’s a pig in it that can talk and everything.’

‘Really? How do they do that?’

‘Come on Matt. We’re losing our place,’ the girl’s voice whined.

‘Dunno,’ said Jamie. ‘I suppose they must’ve taught it to.’ He was doing everything in his power to prolong this agonising encounter.

‘Must’ve been some bright pig,’ said ‘Matt’. I knew his name now — Matt. He was being really nice to Jamie for some reason.

There was more hassle coming from the girl, who was through the doors by now.

‘OK, I’m coming …’ I heard him say, and then they went ahead of us and bought their tickets and disappeared arm-in-arm into Screen 2.

Gemma gazed after him. ‘He is gorgeous,’ she sighed.

‘But he’s got a girlfriend,’ I pointed out. ‘So forget it.’

Gemma then proceeded to give me the benefit of worldly-wise advice gleaned from her obsessive romance reading — like how ‘true love’ always had to overcome all sorts of totally impossible obstacles which made it all so much more worthwhile in the end.

‘Thanks a lot Gem, that’s a big comfort.’

I didn’t have the heart to point out that, in real life, guys like him went out with girls like the one he was with — and girls like me went to see Babe with their kid brother and sister.

Chapter Seven

Saturday morning. Mum likes to use Saturdays to catch up on chores. So it had become a sort of ritual that Dad and I should make the routine shopping expedition to the supermarket. I had an ulterior motive, of course, like making sure decent shampoo and conditioner found its way into the trolley, not just family stuff — and slipping in things like Fruit Comers and Coco Pops when he wasn’t looking. If Dad had his own way he’d come out with an entire trolley of unwashed, unwrapped, organically-grown fruit and veg. He has this real thing about packaging, keeps ranting on about what a waste of the worlds resources it is. In Dad’s ideal world, we’d all have to juggle our groceries home with our pockets filled with detergent. So for Dad, Saturday mornings at Sainsbury’s isn’t just shopping — its a crusade.

We’d stocked up on fruit and veg and Dad had given a lady who was helping herself to a stash of special mushroom bags a lecture on criminal waste — when I spotted Matt.

He was with that alkie guy — the one who looked as if he’d been guzzling vodka on number twenty-fives front wall. The alkie guy actually had an open can of lager in his hand, and between bouts of slopping it everywhere, he was drinking out of it. Their trolley was packed sky-high with booze. A third guy, who was huge and ferocious-looking with matted dreadlocks, was tagging along behind. I knew Dad would throw a wobbly if he saw them. I steered our trolley into safer territory between the cereal aisles and started up a distracting argument about the virtues of Kelloggs versus Own Brand Cereals. I knew this would get him going.

‘They’re all made by the same people, Natasha.’

‘No they’re not. Says so on the packet.’

‘It’s basically the same stuff inside, though.’

‘It can’t be.’

Dad was well into a tirade against branded goods when we moved on to Jams and Preserves. Since it was Saturday morning the place was pretty crowded. At this rate I just might get Dad out of the supermarket without him spotting the guys.

All went well as we went full steam ahead through tinned foods and stocked up on pasta. Nearing the end of the maze of aisles, we reached pet foods. I was reminding Dad of the varieties of cat food that Yin and Yang would or would not currently eat.

‘What do you mean, they’ll eat Chicken & Rabbit but not Chicken & Turkey? Those can’t taste much different.’

‘Maybe they read the labels.’

‘Well, they’re getting Own Brand. I’ve never heard of brand-conscious cats.’

‘That is so unfair; Dad. They don’t do Own Brand Salmon & Shrimp — and that’s their favourite.’

‘One tin, Natasha — for a treat. And that’s their lot.’

So all we had left to do now was detergents. We rounded the top of the Shampoo and Soaps aisle and as luck would have it, there they were. The alkie guy with the flat-top haircut was throwing his weight around, having some sort of argument with one of the shelf-stackers. He had him by the lapels.

Dad stopped in his tracks.

‘Just look at that,’ he said. ‘Disgusting.’

‘Mmmm,’ I said.

But Dad hadn’t homed in on the aggressive little scene in Wines and Spirits. His interest was closer to home. He’d picked up a box containing a hideous plastic crinoline lady full of strawberry-scented bubble bath.

‘It’s criminal! An outer pack — an inner pack — about ten grams of high grade coloured plastic — and all to package a teaspoonful of artificial strawberry-scented detergent. Do you know what stuff like this is doing to the ozone layer?’

‘Making a hole in it, Dad,’ I replied dutifully.

‘Too right it is,’ he said, passing the pack to me. He took charge of the trolley and steamed off towards the check-out. ‘Come on, we’re going to take a stand on this one.’ I was left to trail behind carrying the gross crinoline lady.

I’d had scenes like this before. Incredibly mortifying scenes with everyone staring at us as if we’d gone totally insane. Scenes with poor harrassed staff trying to keep their cool and churn out all that ‘the customer’s always right’ stuff they learn in supermarket school, while Dad ranted on making a total prat of himself.

Dad had rounded the bend at the end of Shampoos and Conditioners when we were caught in a knot of people. A traffic jam of trolleys and mums and kids had built up. That’s when we came face to face with them.

The guy with the dreadlocks took one look at what I was carrying, raised an eyebrow and made an ‘isn’t it cute’ face. The guy with the square-topped hairdo raised his can of lager like a salute and he just said ‘Hi.’

‘Hi,’ I said. And then they moved on.

Dad stood there staring after them. ‘Do you know those people?’

‘Yes, no … Umm, one of them lives in our street … I think.’

‘Not that squatter that’s moved into number twenty five?’

Dad didn’t need an answer, my face said it all.

‘Nice friends he’s got. Your mother’s right. You don’t want to have anything to do with them.’

‘Yes, Dad.’

Dad continued positively fuming. We joined a checkout queue and I dutifully started to load the conveyor.

‘And what about that?’ asked the girl, indicating the bubble bath I was holding. ‘Do you want it or don’t you?’

‘Want it? How could anyone want anything as repulsive as that?’ demanded Dad.

The check-out lady looked affronted. She obviously wasn’t used to having people criticising her merchandise. Well, if you don’t want it, just leave it on one side.’

‘I don’t want it. I want to take it through and complain about it.’

‘You’ll have to pay for it first then and get a refund.’

Dad looked as if he was about to explode.

‘You are asking me to pay for this … This … excrescence?’

‘If you want to take it through, yes.’

A little queue was building up behind us. A lady one back, wearing designer sunglasses with gilt bits on them, stopped devouring the ‘Mediterranean Recipe’ card she’d pinched from the rack and gave us a withering glance.

‘I say. Why don’t you just jolly well pay and be done with it?’ she said.

‘Yes,’ agreed a guy three or so people back. We haven’t got all morning.’ He was wearing a tight T-shirt that read ‘Expansion Tank’ across his stomach and didn’t look like the kind of person you’d want to have an argument with. A baby strapped into a plastic seat set up a mournful howl in agreement.

‘I’d like to speak to the Manager.’ Dad was standing his ground.

The check-out lady put her on her little flashing light with a sigh and we all stood and waited.

‘Look mate, why don’t you just pay for what you’ve got and ‘op-it,’ said the bloke in the expandable T-shirt.

I don’t really want to go into the details. Let’s just say we came very close indeed to causing a riot and ended up at the Complaints Desk with an angry crowd gathered round Dad listening to his standard speech on the evils of packaging and the imminent destruction of rainforests and polar icecaps and the inundation of most of the Netherlands. I stood a few yards away, guarding our trolley, praying for an earthquake to cause a gaping hole to appear in Sainsbury’s floor and swallow me up.

And yes, the boys had reached the check-out. They weren’t going to be allowed to miss out on a scene like this. Oh no. They were finding the whole situation most fun. I could see the flat-top haircut guy practically peeing himself. Dreadlocks was doing a pretty good imitation of Dad by the look of it.

Naturally, they took forever going through — one of their crates of lager wasn’t bar-coded and they had to send an assistant back to check the shelves. I’d moved away, hoping to disassociate myself from Dad’s agonisingly embarrassing performance. But my eyes kept gliding back to check if the boys were still watching him.

That’s when our eyes actually met. You read all those corny things about ‘eyes meeting’. I mean, I’d always thought the whole eye-contact thing was a vast overclaim. But even from this distance, I could see that his were greeny-hazel and kind of — intense. They went right through me. To add the ultimate touch to my humiliation, I felt myself blushing. I had to turn round and study a poster for Spicy Thai Prawn Paella to get over it.

When I felt composed enough to turn back, I found they were making for the exit. They’d practically bought up the whole store’s supply of beers. By the look of it they were going to have some party.

Chapter Eight

Just so you get the picture of the full extent of my family’s madness, I’ve got to tell you about Dad’s pet project.

Dad’s pet project is up in the loft. He’s taken over the whole loft area and he’s pinned out all the pages of the A-Z road atlas side by side, each page butting to the next so that we’ve got an incredibly detailed plan of London, street by street. He’s working on his own alternative traffic plan. He seems to think that the future of the planet lies in pedal power. So he’s tracing all these little cycle-ways through the city. Most weekends you’ll see us setting out as reluctant researchers on one of his reccies. First Dad on his mountain bike. Then Mum on her old upright. Followed by Jamie and Gemma and lastly me on my cringe-making pink Raleigh. To complete the picture, we all have to wear these really nerdy cycle helmets and pollution masks. Give us ears and we’d look like a group outing of koala bears.