Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Graves’s campaign against the bars was, in fact, a battle against the city’s raucous history. Since its founding, Paterson had been the Wild West on the Passaic, where bare-knuckled industrialists converged with brawny immigrants and infamous scoundrels. Alexander Hamilton, smitten by the Great Falls of the Passaic River, founded Paterson in 1791 with the belief that water-powered mills would turn the city into a laboratory for industrial development. Initially, Paterson was not a city at all but a corporation, called the Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufacturers, or SUM. The Panic of 1792 almost sank SUM, but it survived, and Paterson flourished as a freewheeling outpost of frontier industrialism.

Fueled by iron ore from nearby mines, charcoal from abundant forests, and coal from Pennsylvania, Paterson in the nineteenth century attracted inventors, romantics, and robber barons who made goods used across the country and beyond. In 1836 Sam Colt, unable to raise money for a factory by roaming the East Coast with a portable magic show, found backers in Paterson, where he manufactured his first revolver. John Holland, an Irish nationalist, built the first practical submarine in Paterson in 1878, his goal being “to blow the English Navy to hell.” (The Brits turned out to be principal buyers of the new weapon.)

It seemed that Patersonians believed anything was possible, reckless or otherwise. In the 1830s “Leaping” Sam Patch, a cotton mill foreman, became the only man to jump off the Niagara Falls successfully without a protective device. (He was less successful jumping off the Genesee Falls; his body turned up in a block of ice on Lake Ontario.) Wright Aeronautical Corporation undertook a more constructive if no less daring mission in 1927: it built a nine-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine that propelled Charles Lindbergh to Paris on the first solo Atlantic flight. Paterson’s most famous product was silk—enough to adorn all the aristocrats in Europe, if not the Victorian homes and furtive mistresses of the silk barons themselves. Silk lured thousands of European immigrants to Paterson. By 1900 they filled three hundred and fifty hot, clamorous mills, weaving 30 percent of all the silk produced in the United States.

Between 1840 and 1900, Paterson’s population increased by 1,348 percent, to 110,000 residents, making it the fastest-growing city on the East Coast. Newly arrived Germans, Irish, Poles, Italians, Russians, and Jews carved out sections of the city, and ethnic taverns followed. By 1900 Paterson had more than four hundred bars, where tipplers bought cheap, locally brewed beer and reminisced about the old country. Even in the 1950s, long after the immigrant waves had been assimilated, the Emil DeMyer Saloon, in the oldest part of the city, north of the river, hung out a sign that read: “French, Dutch, German, and Belgian Spoken Here.”

The bars, of course, were also seen as contributing to alcoholism, broken marriages, and lost weekends. Wives complained to the priest of Saint John the Baptist Cathedral, William McNulty, that their husbands were quaffing down their wages. Dean McNulty, who led the church for fifty-nine years until he died in 1922, would patrol the bars on Friday nights and swat the guzzlers home with his wooden walking stick.

Booze was hardly enough to calm the tensions that stirred in the crowded three-family frame tenements. The factory laborers, with their dye-stained fingers and arthritic backs, chafed at the excesses of the rich. In 1894 Paterson’s largest silk manufacturer, Catholina Lambert, built a hulking medieval castle near the top of Garrett Mountain, hiring special trains to bring four hundred guests to its opening reception. But in the streets below, vandalism was rampant, strikes common, and political passions high. In 1900, when Angelo Bresci, a Paterson anarchist, returned to his homeland of Italy and murdered King Humbert I, a thousand anarchists in Paterson gathered to celebrate. Between 1850 and 1914, Paterson was the most strike-ridden city in the nation. The strife reached its brutal climax in 1913, when a five-month strike left gangs of workers and police roaming the streets and attacking one another. Paterson’s silk industry, and the town itself, never recovered.

While World War II spurred a brief economic revival, mechanization threw weavers out of work, and textile factories needing skilled labor moved to the South. Wright Aeronautical went from a wartime peak of sixty thousand employees to five thousand, then moved to the suburbs. The Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufacturers dissolved in 1946. The Great Falls became a favorite spot for suicides and murder.

Lacking leadership and vision, Paterson continued its long economic slide in the 1960s, and like other cities in New Jersey, it became a wide-open rackets town. Bookies ran the wirerooms in a club on lower Market Street, placing bets on horse races and football games. The most popular form of gambling, the grease that lubricated the Paterson economy, was the “numbers.” It cost as little as a quarter or even a dime, and everyone played, including the cops. Bettors dropped off their money at a storefront, typically a bar but perhaps a bakery or grocery. Bets were made on the closing number of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the winning numbers from a horse race, or the New York Daily News’s circulation number, which was published on the back page in each edition. The following day, the two-bit gamblers either griped about their bad luck or picked up their winnings, typically six hundred times their bet, meaning $60 on a ten-cent wager or $150 on a quarter. Win or lose, they put down another bet. Numbers runners ferried the cash to the mobsters, who controlled the game, and the small business owners who collected the cash got a cut. It was another way for the bustling taverns to stay in business, but it did little to help Paterson regain its glory.

In On Paterson, Christopher Norwood wrote this elegy for the city in the middle 1960s: “The mills, the redbrick buildings where people produced commodities and became commodities themselves, still stand in Paterson, but most are abandoned now. The looms are no more, their noisy, awkward machinery long vandalized or sold for scrap. Vines, weeds and sometimes whole trees have grown through their stark walls, the walls unadorned except for small slits, outlined in a contrasting brick pattern, left for windows.”

This was the city Frank Graves ran from 1960 to 1966. Despite the deteriorating economy, the mayor wanted the police force to be his legacy. Graves himself was a policeman manqué. He had ridden in police cars as a kid and relished the crisp blue uniforms, the recondite radio codes, and the peremptory wail of a car siren. But his father, Frank X. Graves, Sr., would not allow his son to work on the force. Frank Sr. was a city power broker who owned a lucrative cigarette vending-machine company. He also covered the police for the Paterson Evening News for fifty years, and no son of his was going to chase petty thieves on the street. So, as mayor, Frank Jr. gloried in turning the police into his fiefdom. He spent time at the police station and personally answered incoming calls. He approved all hires, assignments, and promotions. He interrogated suspects. He chastised traffic cops who failed to direct cars with sufficient authoritarian snap. He required patrolmen to salute him, and offenders were summoned to the captain’s office the next day for a reprimand. Graves decreed that all police calls receive a response within ninety seconds, resulting in siren-blaring patrol cars careening through Paterson’s narrow streets. “The police force,” Graves said, “is the city.” And no task was too trivial. He once sent a phalanx of patrol cars to a nearby suburb to search for Tiger, a dog who’d strayed from Paterson.

But Graves came under fire for turning the city into a police state; there were charges of brutality and even torture. In 1964 the state ordered Passaic County to convene a grand jury to investigate reports that Paterson police had burned a prisoner’s body with matches and poured alcohol into his nose. The grand jury made no indictments but recommended that the department photograph prisoners both before and after questioning. The barroom raids were seen as grandstanding ploys, sacrificing basic patrol work. Although drug-related crimes were the city’s worst problem, there was only one man in the Narcotics Bureau.

Paterson’s swelling black population especially feared the mostly white police force and resented Graves’s apparent indifference to their grievances. During the Depression, blacks made up less than 2 percent of the city’s population. By the middle 1960s, they were about 20 percent. Between 1950 and 1964, 18,000 blacks and Hispanics moved into Paterson as 13,000 whites moved out. At the same time, good factory jobs were disappearing quickly, creating tensions between whites and blacks for a piece of the shrinking economic pie. Many black immigrants settled in the Fourth Ward and established taverns and nightclubs. Housing there was a shambles. Old wooden structures slouched beneath the weight of their new occupants; many of the units lacked plumbing, central heating, or private baths. A citywide survey showed that when a black family moved into a tenement, the rent was increased. There were long waiting lists for low-income municipal housing, and when blacks tried to move out of the Fourth Ward, they were refused or stalled by white real estate agents. Health conditions were horrid. A protest group offered a bounty of ten cents for each rat found in a home and delivered to City Hall. A court injunction snuffed out the rodent rebellion.

The anger in the black community was finally unleashed in August 1964, when a three-day riot broke out, primarily in the Fourth Ward. No one was killed, but the cataract of violence unnerved white Patersonians, who still made up 75 percent of the city’s 140,000 residents. Black youths shattered more than a dozen store windows at the intersection of Godwin and Graham Streets while a black youngster battling sixteen policemen was pushed through a plate glass window. Factory fires, Molotov cocktails, and errant shotgun blasts sent panic through the city. A marked law enforcement car from Maryland appeared with two German shepherd police dogs, although the authorities said they were never loosed on the rioters. Black leaders blamed the uprising on police harassment and overcrowded housing conditions, saying it was simply too hot to stay indoors, and they demanded rent control in blighted areas and a new police review board.

The riot was part of a summer of uprisings that broke out in Harlem, in Jersey City and Elizabeth, New Jersey, in Rochester, New York, and in small black enclaves in Oregon and New Hampshire. In each case, a street arrest triggered escalating hostilities, but only Paterson had Frank Graves.

The mayor tried to keep control. At a luncheon in Paterson on August 12 for Miss New Jersey, he promised, “Paterson will be completely safe for you tonight.” By nightfall, Graves probably hoped, Miss New Jersey was smiling in some other part of the state, because violence erupted once again in Paterson. Graves personally led the police through a ravaged ten-block area and narrowly missed serious injury when a bottle was thrown at him as he stepped from his car. Confronted by the overturned vehicles, shattered storefronts, and broken streetlights, Graves blamed the riot on “the worst hooligans that man has ever conceived.” His rhetoric, combined with his hard-nosed police, left little doubt among blacks that Graves was less interested in civil rights than civil repression.

Thoughts of race and crime were probably not on the mind of seventeen-year-old William Metzler when he arrived at work on Thursday, June 16, 1966. Metzler was an attendant for his father’s ambulance company in Paterson, working a midnight–8 A.M. shift. Employees stayed awake for two-hour stretches, sipping coffee, eating doughnuts, and monitoring the police radio. Some time after 2 A.M. on June 17, Metzler began hearing a series of police calls amid escalating panic. One call said, “Holdup.” Another: “Shooting.” And yet another, “Code one for ambulances,” which meant emergency.

Metzler and his older brother, Walt, raced their ambulance twelve blocks to the scene of the crime: the Lafayette Grill at 128 East Eighteenth Street, a nondescript neighborhood bar on the first floor of a tired three-story apartment building. When the ambulance arrived, a police car and two officers were on the site. William Metzler opened the bar’s side door, on Lafayette Street, walked inside, and literally slid across the bloody tile floor, almost falling into the red stream. Amid the cigarette and nut machines, a pool rack and jukebox and black-and-white television above the L-shaped bar, a scene of mayhem emerged: there were four bullet-ridden bodies—two dead, two alive, all white. It was, Metzler said years later, “a Wild West scene.”

While the shooting itself would be subject to one of the longest, most bitterly contested criminal proceedings in American history, no one would ever dispute the distinctively sadistic nature of the rampage. These basic facts were known within days.

Two black men entered the bar through the side door, one carrying a 12-gauge shotgun, the other a .32-caliber handgun. The bartender, James Oliver, age fifty-one, flung an empty beer bottle at the assailants, then turned to run. As the bottle shattered futilely against the wall, a single shotgun blast from seven feet away ripped through Oliver’s lower back, opening a two-by-one-inch hole. The bullet severed his spinal column, literally breaking the man in half. Oliver fell behind the bar, dead, two bottles of liquor lying near his tangled feet and cash strewn on the floor.

At about the same time the second assailant, holding the handgun, fired a single bullet at Fred Nauyoks, a sixty-year-old regular sitting on a barstool. The bullet ripped past Nauyoks’s right earlobe and struck the base of his brain, killing him instantly. He slumped over as if asleep, his head lying in a pool of blood, a lit cigarette between his fingers, his shot glass full, and cash on the bar ready to pay for the fresh drink. His foot remained on the stool’s footrest.

The pistol-carrying gunman then fired a bullet at William Marins, a forty-three-year-old machinist who had been at the bar for many hours, sitting two stools down from Nauyoks. The bullet entered his head near the left temple, caromed through the skull, and exited from the forehead by the left eye. He survived his wound and was able to describe the assailants to the police.

Seated in a different section of the bar was fifty-one-year-old Hazel Tanis, who had just arrived from her waitressing job at the Westmount Country Club. The assailant with the shotgun fired a single blast into her upper right arm. Then the second shooter turned and emptied his remaining five bullets, the muzzle of the gun as close as ten inches from the victim. Four bullets struck their mark: the right breast, the lower abdomen, the vagina, and the genital area. Tanis survived and was able to describe the gunmen to the police, but she developed an embolism four weeks later and died.

From the outset, the Lafayette bar murders became intertwined with another brutal homicide in Paterson. About six and a half hours earlier, a white man named Frank Conforti walked into the Waltz Inn, about four blocks from the Lafayette. Conforti had sold the bar to a black man, Roy Holloway, who was paying him in weekly installments. On this night, Conforti came to collect his last payment, but a heated argument broke out over the amount owed. Conforti stormed out of the tavern and returned moments later with a double-barreled shotgun. He blasted Holloway in the upper right arm; when Holloway tried to flee, he fired again, this time striking him in the head. Conforti was arrested for murder.

The police immediately suspected that the Lafayette bar shooting was in retaliation for the Waltz Inn murder. At the Waltz Inn, a white man with a shotgun killed a black bartender. At the Lafayette bar, a black man with a shotgun killed a white bartender. An eye for an eye. The Lafayette bar slaying chilled the white establishment. Black vigilantism, of course, was unacceptable. What’s more, the bar itself had long been a tiny neighborhood hangout for the Italians, Lithuanians, Poles, and other Eastern European immigrants who lived on the southern boundary of the working-class Riverside section.

But by the summer of 1966, the neighborhood was changing quickly. Blacks, moving north along Carroll and Graham Streets, were now living near and around the Lafayette bar. But the bar was still a watering hole for its traditional base of white workers, not blacks. Indeed, rumors circulated that the bartender refused to serve blacks. In time the bar, under different owners and different names, would be a black gathering spot for a black neighborhood. But on June 17, 1966, it was seen as a white redoubt against a coming black wave.

For a city the size of Paterson, the Lafayette bar shootings—four innocent victims, including one woman, three ultimately dead—would have been jarring under any circumstance. There had been only six murders in Paterson since the beginning of the year. But the overlay of race, of black invaders and white flight and a hapless neighborhood bar with a neon Schlitz sign and threadbare pool table, elevated the tragedy further.

Frank Graves assigned 130 police officers (out of a force of 341) to the investigation, promising promotions and three-month vacations to the arresting officers. He initially offered a $1,000 reward for information that led to an arrest, then raised it to $10,000. The Paterson Tavern Owners Association chipped in another $500. That the crime occurred in a bar confirmed the mayor’s conviction that taprooms were whirlpools of disorder. “We have three hundred and fifty” taverns, Graves thundered. “We should only have a hundred.”

He repeatedly referred to the Lafayette bar murders as “the most heinous crimes” and “the most dastardly crimes in the city’s history.” Two days after the shooting, Graves told the Paterson Evening News, “We will stay on this investigation until it is solved. There will be no such thing as a dead end in this case. If we hit a roadblock, we’ll back up and get on the main road until it is solved. These are by far the most brutal slayings in the city’s history.”

The pressure to solve the worst crime in Paterson’s long history would soon lead to the most feared man in the town.

3

DANGER ON THE STREETS

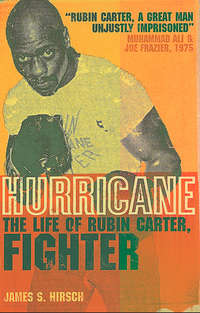

AT THE TIME of the Lafayette bar murders, Rubin Carter was a twenty-nine-year-old prizefighter and one of the great character actors of boxing’s golden era. The middleweight stalked opponents across the ring with a menacing left hook, a glowering stare, and a black bullet of a head—clean-shaven, with a sinister-looking mustache and goatee. Outside the ring, Carter cultivated a parallel reputation of a dashing but defiant night crawler. He settled grudges with his fists and was not cowed by the police. His intimidating style sent chills through boxing foes and cops alike, making him a target for both.

Regardless of where he walked, Carter always turned heads. At five feet eight inches and 160 pounds, he had an oversize neck, broad shoulders, and trapezoidal chest, with contoured biceps, thick hands, a tapering waist, and sinuous legs. A broadcaster once said of Carter, “He has muscles that he hasn’t even rippled yet.”

He was obsessed with fine clothing and personal hygiene, passions he inherited from his father. Lloyd Carter, Sr., believed that immaculate apparel showed a black man’s success in a white man’s world. A Georgia sharecropper’s son with a seventh-grade education, Lloyd earned a good living as a resourceful and indefatigable entrepreneur. He owned an icehouse, a window-washing concern, and a bike rental shop, and he wore his success proudly. He had his double-breasted suits custom-made in Philadelphia, favored French cuffs, and wore Stacy Adams two-tone alligator shoes. He bought his children shoes for school and for church; but if the school shoes had a hole, church shoes could not be worn to classes. No child of his would enter a house of worship with scuffed footwear.

Rubin Carter was just as meticulous as his father, if somewhat flashier. He instructed a Jersey City tailor to design his clothes to fit his top-heavy body. He placed $400 suit orders on the phone—“Do you have any new fabrics? … Good. Put it together and I’ll pick it up”—and he favored sharkskin suits, or cotton, silk, all pure fabrics, an occasional vest, and iridescent colors. His pants were pressed like a razor blade. He wore violet and blue berets pulled rakishly over his right ear, polished Italian shoes, and loud ties.

Carter trimmed his goatee with precision and clipped his fingernails to the cuticle. He collected fruit-scented colognes while traveling around the United States, Europe, and South Africa, then poured entire bottles into his bath water, soaked in the redolent tub, and emerged with a pleasing hint of nectar. Every three days Carter mixed Magic Shave powder with cold water and slathered it on his crown and face. He scraped it off with a butter knife, then rubbed a little Vaseline on top for a shine. His wife, Tee, complained that the pasty concoction smelled like rotten eggs, so she made him shave on their porch, but the result was Carter’s riveting signature: a smooth, shiny dome.

Nighttime was always Carter’s temptress, a lure of sybaritic pleasures and occasional danger. On his nights out, he left his wife at home and cruised through the streets of Paterson in a black Eldorado convertible with “Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter” emblazoned in silver letters on each of the headlights. He strolled into nightclubs with a wad of cash in his pocket and a neon chip on his shoulder. He bought everyone a round or two of drinks and mixed easily with women, both white and black. An incorrigible flirt, he danced, drank, and cruised with different women most every night.

But club confrontations often got Carter in trouble. He faced assault charges at least twice for barroom clashes, including once from the owner of the Kit Kat Club. Carter, contending he was unfairly singled out because of his swaggering profile, was cleared. But stories swirled about his hair-trigger temper. In an oft-repeated tale, Carter once found a man sitting at his table at the Nite Spot. When the man was slow to leave Hurricane’s Corner, Carter knocked him out with a punch, then took his girl.

Carter pooh-poohs such tales, although he says he would have told the man to sit elsewhere if other tables had been available. His dictum was that he never punched anyone unless first provoked, but he acknowledges that he was easily antagonized and, once aroused, showed little mercy on his tormentor. Adversaries came in all stripes. He once knocked a horse over with a right cross. The horse had had it coming: it tried to take a bite out of Carter’s side. The knockdown, publicized in local and national publications, added to Carter’s street-fighter reputation and legendary punching prowess.

Hedonistic excess was hardly uncommon in the boxing world; nonetheless, it was not widely known that Carter was an alcoholic during his career. Some thought Carter drank to make up for his dry years in prison: between 1957 and 1961, Carter had been sentenced to Trenton State Prison for assault and robbery. The inmates surreptitiously made a sugary wine concoction, “hooch,” but good liquor was hard to come by.

Outside prison, vodka was Carter’s drink of choice. Straight up, on the rocks, in a plastic cup, in a glass, from a bottle, it didn’t matter; it just had to be vodka. He was not a binge drinker but a slow, relentless sipper, and he could drink a fifth of vodka in a single night. Carter stayed clear of the bottle, mostly, when in training, but when he was out of camp, he kept at least one bottle of 100-proof Smirnoff’s in his car; friends hitching a ride got free drinks.

Carter concealed his drinking as much as possible. It was a sign of weakness and undermined his image as an athletic demigod. To avoid drinking in clubs, he picked up liquor in stores and drank in his car, sometimes with drinking buddies, sometimes alone. He tried not to order more than one drink at any one club on a given night. His wife rarely saw him imbibe and had no idea of the scope of his addiction. He carried Certs and peppermint candies to mask the alcohol on his breath, and he never got staggering drunk.