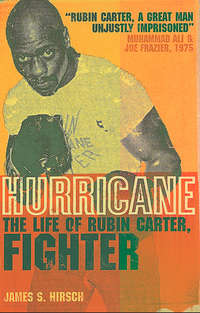

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Carter was also petrified. He had no idea where they were heading, only that they had turned East Eighteenth Street into the crazy backstretch of a stock car race. He saw landmarks fly by. There was a cousin’s home on the corner of East Eighteenth and Twelfth Avenue. There was the Nite Spot on the corner of East Eighteenth and Governor. But then the juggernaut sped beyond the black neighborhoods into unknown territory. Finally, the lead police car slowed down and made a sharp left turn at Lafayette Street, five blocks north of the Nite Spot. A crowd of people in the brightly lit intersection scattered as the pacer car screeched to a halt. The other vehicles followed suit.

Everything seemed to be in miniature. The streets were so narrow, the intersection so compressed, that any car whipping around a corner could easily crash into an apartment building or a warehouse. “What the fuck are we doing here?” Carter blurted. Neither he nor Artis had ever been inside the Lafayette bar; Carter had never even heard of the place. These are not my digs, but whatever went down, it had to be bad.

A scene of chaos lay before them. An ambulance had pulled up next to the bar, where a bloodstained body was being hauled out on a stretcher beneath the neon tavern sign. The throng of mostly white bystanders, many in pajamas, robes, or housecoats, milled about the Dodge, parked on Lafayette Street and hemmed in by police cars. There was panicked crying and breathless cursing, the slap of slamming car doors, and the errant static of police radios. Whirling police lights gave the neighborhood’s old brick buildings a garish red light as about twenty white cops, wearing stiff-brimmed caps, shields on their left breast, and bullet-lined belts, whispered urgently among one another.

The neighbors, some weeping, began to converge on the Dodge. Peering into the open windows, they looked at the two black men with anger and suspicion. Carter and Artis both sat frozen, unclear why they had been brought there but fearing for their lives. This is how a black man in the South must feel when a white mob is about to lynch him, Carter thought, and the law is going to turn its head. Finally, a grim police officer approached Artis.

“Get out of the car.”

“Do you want me to take the keys out?”

“Leave the keys.”

Then another officer intervened. “Bring the keys and open the trunk!”

“No problem,” Artis said.

As Artis headed to the rear of the car, Carter hesitated. If I get out of this car, it could be the worst mistake I’ve ever made. Artis opened the trunk, and a cop rummaged through Carter’s boxing gloves, shoes, headgear, and gym bag.

Another officer motioned to Carter to step out. Carter opened the door, but he had held his tongue long enough. “What the hell did you bring us here for, man?”

“Shut up,” the officer shouted as he cocked the pistol. “Just get up against the wall and shut up, and don’t move until I tell you to.”

As Carter and Artis walked toward the bar at the corner of Lafayette and East Eighteenth, a hush settled over the crowd. With bystanders forming a semicircle around the two men, Carter and Artis stood facing a yellow wall bathed in the glare from headlights. Artis turned his right shoulder and searched for a familiar face, maybe someone from racially mixed Central High School, his alma mater, but he saw only white strangers. The police frisked them brusquely but found nothing on them or in Carter’s car or trunk. Another ambulance arrived, and Artis felt the hair on his neck rise when he saw another body, draped in a white sheet, roll past him on a stretcher.

Finally, a paddy wagon pulled up and someone shouted, “Get in!” Carter and Artis stepped inside and were whisked away. Sitting by themselves, the two men were once again speeding through Paterson, heading to the police headquarters downtown. No one had asked them any questions or accused them of anything. They could see the driver through a screen divider but were otherwise isolated. “Something terrible is going on, but what’s it got to do with us?” Artis asked.

Carter, disgusted, told him to stay calm. “Don’t volunteer anything, but if someone asks you any questions, tell them the truth. The cops are just playing with me, as usual. It’ll all be cleared up soon.”

The paddy wagon stopped downtown, and the doors swung open at police headquarters. Built in 1902 after a devastating fire wiped out much of Paterson, the building is a hulking Victorian structure with dark oak desks and wide stairways. But Carter and Artis had barely gotten inside when there was another commotion. “Get back in!” someone shouted, and the two men returned to the wagon, which peeled off again. Now they headed on a beeline south on Main Street, eventually stopping at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Paterson’s oldest, where plainclothes detectives were waiting. Carter and Artis were hustled out of the truck and into the emergency room. Everything seemed white, the walls and curtains, the patients’ gowns and nurses’ uniforms, the floor tile and bedsheets. The room had that doomy hospital smell of ether and bedpans and disinfectant. The only patient was a balding white man lying on a gurney, a bloody bandage around his head, an intravenous tube rising from his arm, and a doctor working at his side.

“Can he talk?” asked one of the detectives, Sergeant Robert Callahan.

The doctor, annoyed at the intrusion, shot a disapproving glance at the detective, then at Carter and Artis. “He can talk, but only for a moment.” The doctor lifted the lacerated head of William Marins, shot in the Lafayette bar. The bullet had exited near his left eye, which was now an open, serrated cut. He was pallid and weak.

“Can you see clearly?” Callahan asked the one-eyed man. “Can you make out these two men’s faces?”

Marins nodded his head feebly. Callahan pointed to Artis. “Go over and stand next to the bed.” Artis walked over.

“Is this the man who shot you?” Callahan asked.

Marins paused, then slowly shook his head from side to side. Callahan then motioned for Carter to step forward. “What about him?”

Again, Marins shook his head.

“But, sir, are you sure these are not the men?” Callahan asked in a harder voice. “Look carefully now.”

Carter had been relieved when the injured man seemed to clear him and Artis. But now he concluded the police were going to do whatever they could to pin this shooting on them. Previous assault charges against Carter had been dismissed. Police surveillance had yielded little. Now, this: pell-mell excursions through the night, an angry mob outside a strange bar, a one-eyed man lying in agony, and Carter an inexplicable suspect. He had had enough. As Marins continued to shake his head, Carter closed his eyes, clenched his fists, and spilled his boiling rage. “Dirty sonofabitch!” he yelled. “Dirty motherfucker!”

Back at police headquarters, in the detective bureau, Carter found himself in a windowless interrogation room. It was familiar ground. He had been questioned in the same room twenty years earlier for stealing clothing at an outdoor market. (His father had turned him in.) Two battered metal chairs and a table sat beneath a cracked, dirty ceiling. Artis was left to stew in a separate room, which had green walls, a naked light bulb, and a one-way mirror in the door. Artis could see, between the door and the floor, the black rubber soles of the officers outside his door. He knew they were watching him.

Both men lingered in their separate rooms for several hours, their alcoholic buzz long worn off. They simply felt exhaustion. At around 11 A.M., the door to Carter’s room opened and Lieutenant Vincent DeSimone, Jr., walked in. The two men had a history. DeSimone joined the Paterson Police Department in 1947 and had been one of the officers who questioned the teenage Carter after he assaulted the man at the swimming hole. DeSimone was a coarse and intimidating old-school cop, who would quip about suspects, “He’s so crooked, they’ll have to bury him standing up.” A relentless interrogator, he was known for his ability to elicit confessions through threats and promises. He would do anything for a confession, including pulling out a string of rosary beads to bestir a guilty conscience. He hated the 1966 Miranda decision, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that no confession can be used against a criminal defendant who was not advised of his rights. The ruling, DeSimone feared, gave confessed criminals a loophole.*

In the 1950s he joined the Passaic County Prosecutor’s Office as a detective specializing in homicides, and he was known for keeping index cards in his pocket so he wouldn’t have to carry a notebook. His bosses viewed him as the finest law enforcement official in the state, their own Javert, and his power and reputation were unquestioned.

But on the streets of Paterson’s black community, DeSimone had a different reputation entirely, for he embodied the racist, bullying tactics of an overbearing police force. His confessions had less to do with gumshoe police work than with intimidation, and he was feared. Frankly, he looked scary. In World War II he had taken a grenade blast in the face, and despite several surgeries, his jowly visage was disfigured. A scar inched across his upper lip, which was pulled tightly back, and drool sometimes gathered at the side of his mouth. He had thick eyeglasses, spoke in a gravelly voice, and wore an open sport jacket across his thick, hard gut, revealing his low-slung holster.

DeSimone was tense when he entered Carter’s holding room. He had been awakened at 6 A.M. with news of the shooting, and he stopped off at the crime scene before going to the police station. Despite his many years in police work, this was his first interrogation for a multiple homicide.

“I’m Lieutenant DeSimone, Rubin. You know me.” He sat down heavily and pulled out his pen and paper.

“You can answer these questions or not,” he continued. “That’s strictly up to you. But I’m going to record whatever you say. Just remember this. There’s a dark cloud hanging over your head, and I think it would be wise for you to clear it up.”

“You’re the only dark cloud hanging over my head,” Carter said.

DeSimone was joined by two or three other officers. Over the next couple of hours, Carter recounted his whereabouts on the previous night, from the time he left his home after watching the James Brown special to his two encounters with Sergeant Capter. He mentioned his trip to Annabelle Chandler’s and various club stops. When DeSimone finally told Carter that four people had been shot, Carter waved off the suspicion: “I don’t use guns, I use my fists. How many times have you arrested me around here for using my fists? I don’t use guns.”

Carter was certain the interrogation was just another example of police harassment for his bellicose reputation. He felt his position on fighting was well known to DeSimone and the other officers: he would fight only if provoked. He did not imagine that even an old antagonist like DeSimone would consider him a suspect for killing people inside a bar he had never entered.

During the questioning, DeSimone shuttled back and forth between Carter and Artis in parallel interrogations. It was more difficult to write down the answers from Artis, who spoke faster. DeSimone also told Artis that “there was a dark cloud hanging over you,” but he said the young man had a way out. “When two people commit a murder, you know who gets the short end of the stick? The guy who doesn’t have a record, and you don’t have a record. That’s the guy they really stick it to. Tell us what you know.”

“I don’t know anything,” Artis said.

By midday Carter’s wife heard he had been picked up, and she came to the station.

“Do you want me to call a lawyer?” Tee asked.

“What do I need a lawyer for?” Carter responded. “I didn’t do anything, so I’ll be out of here shortly.”

Later, while Carter was heading to the bathroom, he was taken past several witnesses who supposedly saw the assailants fleeing the crime scene. One was Alfred Bello, a squat, chunky former convict who was outside the bar when the police arrived. He told police at the crime scene that he had seen two gunmen, “one colored male … thin build, five foot eleven inches. Second colored male, thin build, five foot eleven inches.” Another was Patricia Graham, a thin, angular brunette who lived on the second floor above the bar and said she saw two black men in sport coats run from the bar after the shooting and drive off in a white car. Both Bello and Graham would later provide critical testimony in the state’s case against Carter, giving different accounts from those in their initial statements.

A police officer asked the group of witnesses if they recognized Carter. “Yeah, he’s the prizefighter,” someone said. Asked if he had been spotted fleeing the crime scene, the witness shook his head.

After DeSimone completed his questioning of Carter, he gathered up his papers. “That’s good enough for the time being, but there’s one thing more that I’d like to ask. Would you be willing to submit to a lie detector test?”

“And a paraffin test, too,” Carter said without hesitation. “But not if any of these cops down here are going to give it to me. You get somebody else who knows what he’s doing.”

At 2:30 P.M., Sergeant John J. McGuire, a polygraph examiner from the Elizabeth Police Department, met Carter in a separate room. A barrel-chested man with short hair, McGuire had just been told about the shootings, and he was in no mood for small talk. “Carter, let me tell you something before you sit down and take this test,” he said in a tight voice. “If you have anything to hide that you don’t want me to know, then don’t take it, because this machine is going to tell me about it. And if I find anything indicating that you had anything to do with the killing of those people, I’m going to make sure your ass burns to a bacon rind.”

“Fuck you, man, and give me the goddamn thing.”

McGuire wrapped a wired strap around Carter’s chest, and Carter put his fingers in tiny suction cups. He answered a series of yes-or-no questions and returned to his holding room. After another delay, McGuire showed up and laid out a series of charts tracking his responses. DeSimone and several other officers were there as well. Pointing to the lines on the chart, McGuire declared, “He didn’t participate in these crimes, but he may know who was involved.”

“Is that so?” DeSimone asked.

“No, but I can find out for you,” Carter said.

Sixteen hours after they had been stopped by the police, Carter and Artis were released from the police station. Carter was given his car keys and went to the police garage, only to find that the car’s paneling, dashboard, and seats had been ripped out. The following day, June 18, Assistant County Prosecutor Vincent E. Hull told the Paterson Morning Call that Carter had never been a suspect. Eleven days later Carter, as well as Artis, testified before a Passaic County grand jury about the Lafayette bar murders. DeSimone testified that both men passed their lie detector tests and that neither man fit the description of the gunmen. Notwithstanding the adage that a prosecutor can indict a ham sandwich—prosecutors are given a wide berth to introduce evidence to show probable cause—the prosecutor in the Lafayette bar murders failed to indict anyone. Carter traveled to Argentina and lost his fight against Rocky Rivero. The promoter never did give him a sparring partner. The thought flashed through Carter’s head that he should just stay in Argentina, which had no extradition treaty with the United States. That way, the Paterson police would no longer be able to hassle him. Instead he returned home.

On October 14, 1966, Carter was picked up by the police and charged with the Lafayette bar murders.

* FBI files released through the Freedom of Information Act indicate that Carter was under investigation at least by 1967. The report could not be read in full because the FBI had blacked out many sections, evidently to protect its informants.

* The Miranda decision had been issued only days before the Lafayette bar murders. DeSimone testified that he gave Carter his Miranda warning, which Carter denies.

4

MYSTERY WITNESS

IT WAS THE BREAK everyone had been waiting for. On October 14, 1966, the front page of the Paterson Evening News screamed the headline: “Mystery Witness in Triple Slaying Under Heavy Guard.” A three-column photograph, titled “Early Morning Sentinels,” showed tense police officers in front of the Alexander Hamilton Hotel on Church Street guarding the “mystery witness.” An unnamed hotel employee said he saw the police hustle a “short man” into an elevator the day before at 6 P.M. The elevator stopped on the fifth floor, where a red-haired woman was seen peering out from behind a raised shade.

The newspaper story raised as many questions as it answered, but the high drama indicated that a breakthrough had occurred in the notorious Lafayette bar murders, now four months old. Excitement swirled around the Hamilton, where a patrol car was parked in front with two officers inside, shotguns at the ready. Roaming behind the hotel were seven more officers, guarding the rear entrance. A police spotlight held a bright beam on an adjoining building’s fire escape, lest an intruder use it to gain access to the Hamilton. Two more shotguntoting cops stood inside the rear entrance, and detectives roamed the lobby. Overseeing the security measures, according to the newspaper, was Mayor Frank Graves.

John Artis saw the headline and thought nothing of it. He assumed he had been cleared of any suspicion of the Lafayette bar shooting after he testified before the grand jury in June and no indictments had been issued. At the time, Artis was at a crossroads in his own life. His mother had died from a kidney ailment a month after he graduated from Central High School in 1964. Mary Eleanor Artis was only forty-four years old, and her death had devastated John, an only child. He knocked around Paterson for several years, working as a truck driver and living with his father on Tyler Street. In high school, he had been a solid student and a star in two sports, track and football, and he sang in the choir at the New Christian Missionary Baptist Church. He had giddy dreams of playing wide receiver for the New York Titans (later known as the New York Jets). He also had a bad habit of driving fast and reckless—he banged up no fewer than eight cars—but he had no criminal record and never had any problems with the police. Neither of his parents had gone to college, and they desperately wanted their only child to go. By the fall of 1966, Artis had been notified by the Army that he had been drafted to serve in Vietnam, but he was trying to avoid service by winning a track scholarship to Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado, where his high school track coach had connections.

On October 14, dusk had settled by the time Artis finished work. It was Friday, the night before his twentieth birthday, and an evening of dancing and partying lay ahead. He stopped at a dry cleaner’s to pick up some shirts, then went into Laramie’s liquor store on Tyler Street to buy an orange soda and a bag of chips. He and his father lived above the store. As he was paying for the soda, the door of the liquor store swung open. “Freeze, Artis!” a cop yelled. “You’re under arrest!”

Artis saw two shotguns and a handgun pointed at him. “For what?” he demanded.

“For the Lafayette bar murders!”

“Get outta here!”

Police bullying of blacks in Paterson was so common that Artis thought this was more of the same, an ugly prank. But then two officers began patting him down around his stomach and back pockets. Artis handed his clean shirts to the liquor store clerk and told him to take them to his father. His wrists were then cuffed behind his back. Damn, Artis thought, these guys are serious! On his way out of Laramie’s, Artis yelled his father’s name: “JOHHHHN ARTIS!” As he was shoved into a police car, Artis saw his father’s stricken face appear in the second-story window.

Rubin Carter was at Club LaPetite when one of Artis’s girlfriends approached him with the news: John had been arrested.

“For what?” Carter asked.

“I don’t know, they just arrested him.”

Like Artis, Carter had seen the “Mystery Witness” headline in the newspaper but hadn’t given it a second thought, and he didn’t connect the headline to Artis’s arrest. Carter, distrustful of the police, feared for Artis’s safety, so he got into his Eldorado and drove to police headquarters to check up on the young man. As he neared the station, he put his foot on the brake; then, out of nowhere, detectives on foot and in unmarked cars swarmed around his car.

“Don’t move! Put your hands on the wheel! Don’t move!”

Here we go again, was all Carter could think. But this police encounter proved to be much more harrowing than his June confrontation. His hands were quickly cuffed behind his back, and he was shoved into the back seat of an unmarked detective’s car. According to Carter, the officers did not tell him why they had stopped him or what he was being charged with. Instead, with detectives on either side of him, the car doors slammed shut and the vehicle sped away, followed by several other unmarked cars. Carter had no idea where they were going, or why. Soon the caravan headed up Garrett Mountain, cruising past the evergreens and maple trees. Even at night Carter knew the winding roads because he often rode his horse on the mountain. The motorcade finally came to a stop along a dark road, and there they sat. Detectives holding their shotguns milled around, and Carter heard the crackling of the car radios and officers speaking in code. They did not ask him any questions. Damn! They’re going to kill me. They sat for at least an hour, then Carter heard on the car radio: “Okay, bring him in.” He always assumed that someone had talked the detectives out of shooting him.

At headquarters, Carter was met by Lieutenant DeSimone and by Assistant County Prosecutor Vincent E. Hull. It was Hull who spoke: “We are arresting you for the murders of the Lafayette bar shooting. You have the right to remain silent …” The time was 2:45 A.M. Unknown to Carter, Artis had also been taken to Garrett Mountain, held for more than an hour, then returned to headquarters and arrested for the murders. The Evening News said the arrests “capped a cloak-and-dagger maneuver masterminded by Mayor Graves,” who grandly praised his police department: “Our young, aggressive, hard-working department brought [the case] to its present conclusion.”

Some nettlesome questions remained. Though the police searched the city’s gutters and fields and dragged the Passaic River, they never found the murder weapons. The authorities were also not divulging why Carter and Artis killed three people. Robbery had already been ruled out, and the Evening News reported on October 16 that the police had determined there was no connection between the Roy Holloway murder and the Lafayette bar shooting. Such details were unimportant. The Morning News rejoiced at the arrest, trumpeting on the same day that the newspaper “exclusively broke the news that the four-month-old tavern murders were solved.”

Carter figured his arrest was tied to the November elections. Mayor Graves, prohibited by law from running for a fourth consecutive term, was hoping to hand the job over to his chosen successor, John Wegner. What better way to show that the city was under control than by solving the most heinous crime in its history? After the election, Carter reckoned he’d be set free.*

But sitting in the Passaic County Jail, where each day he was served jelly sandwiches, Carter learned through the jailhouse grapevine that two hostile witnesses had emerged. Alfred Bello, the former con who had been at headquarters following the crime, and Arthur Dexter Bradley, another career criminal, were near the Lafayette bar trying to rob a warehouse on the night of the murders. Questioned by the police that night, Bello said he could not identify the assailants. But suddenly his memory had improved. Both Bello and Bradley now told police that they had witnessed Carter and Artis fleeing the crime scene.