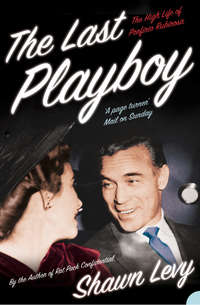

The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa

The source of the president’s contempt was, in Porfirio’s view, obvious: Little Ramfis had been commissioned as a senior officer in the Army the previous year; as Porfirio put it, “What sort of son-in-law would be content to be captain when [Trujillo’s] own five-year-old son was already a colonel?” (A letter from Robert L. Ripley’s “Believe It or Not” offices in New York would arrive on Trujillo’s desk in February 1936, seeking confirmation of Ramfis’s position in the Army and asking whether he wore full uniform and collected the appropriate salary for his rank. By that time, the young soldier had been seen beside his father at several official functions wearing elaborate military uniforms and partaking of champagne toasts.)

But Porfirio endured the Benefactor’s scorn because he simply wanted to be his own man. Without responsibilities as a soldier, he could look for private opportunities around the city. “I had very little to do,” he recalled, “and I wanted to learn about business.” But, as he should have known from his brief stint at the insurance company, nobody did business in Ciudad Trujillo without doing business with Trujillo. And it was a uniquely bold and crafty businessman indeed who could make a success at that.

Félix Benítez Rexach wore his hair to his shoulders, wasn’t too particular about washing or combing it, and habitually topped it with battered straw hats. His clothes weren’t much more presentable: He could show up at official functions in torn and muddy outfits as if oblivious entirely to protocol. He looked for all the world like a hobo, but it was a calculated guise. He was actually a millionaire engineer willing to stand up to gangsters and governments to see his business interests come to fruition. Born in Puerto Rico, he traveled widely and grew especially fond of France, where he owned homes in Paris and on the Riviera. There was suspicious talk about his sexuality, but he had two wives, the second being the onetime Parisian flower girl Gaby Montbre, who had a sort-of musical career as La Môme Moineau (literally, “the bratty sparrow”), a chanteuse in the vein of Edith Piaf. There was suspicious talk as well about his engineering credentials, but he had built himself a yacht from his own design (his wife would become more famous for being photographed by French magazines on its decks in sailing clothes than for her singing), and he had successfully overseen the creation of deep-water harbors in Puerto Rico, where he had additional interests in the resort hotel business.

Benítez Rexach showed up in Ciudad Trujillo in 1934 when Trujillo’s government announced plans to enlarge the harbor at the mouth of the Ozama River; until then, the largest ships arriving in the capital had to anchor a short distance out at sea and have their passengers and cargo ferried ashore. The project would require the use of a massive shipboard dredge—and whoever successfully completed the job could hope on doing further business with Trujillo at other ports around the country.

Benítez Rexach read all the implications of the situation, including the nepotistic nature of Dominican political and business affairs, and he sought a pry hole that would get him into the president’s good graces. He found one in Trujillo’s tomcatting son-in-law. He dangled his wife as bait in front of Porfirio, cynically affording him ample opportunity to sample her favors. (Flor knew about the affair and so, she claimed, did the whole city, including her father.) To tie the knot tighter, Benítez Rexach suggested a business partnership: If Porfirio acquired a dredge, and Benítez Rexach knew of one available in New Orleans, then the engineer would rent it for the duration of the job; they drew up an agreement.

For Benítez Rexach, it was politics: cozen the son-in-law to get to the real power. But for Porfirio and Flor, it was a lifeline—and a gamble. “Neither of us had much business sense,” Flor recalled. She and her husband “were alike in so many ways, neither of us really good-looking, both mixed-up Dominicans, in love with the high life, hungry for what money could buy, but unable to earn an honest living on our own.” Success in the harbor project, however, would mean autonomy from Trujillo’s money and influence. The risk was worth it.

The first obstacle would be getting the capital necessary to buy the dredge. Flor’s father still controlled the $50,000 dowry; would he be willing to open the purse for the project? Willing wasn’t exactly the word. “I don’t have much faith in second-hand machinery or in this investment,” the president told his daughter even as he agreed to her request. Rubi sent an emissary, cash in hand, to buy the dredge, a vessel called the Tenth of February, and bring it back to Ciudad Trujillo.

While he was risking his fortune and good name, such as they were, in this scheme, Porfirio was also upholding his share of the bargain he’d struck with Benítez Rexach, establishing a connection between the engineer and Trujillo. Eventually, the two men so bonded that an intermediary was unnecessary; Benítez Rexach sufficiently impressed Trujillo, in fact, that he was routinely forgiven the effrontery of strolling into the immaculate palace in his grubbiest condition and eventually enjoyed brief appointments from the president in the diplomatic service in France and Puerto Rico.

With these two in cahoots, it was only a matter of time before Porfirio was frozen out. The blindside was delivered with an assassin’s cunning. By the time the Tenth of February was in Ciudad Trujillo and ready to dig, Benítez Rexach had acquired a brand-new dredge of his own for the job and had convinced Trujillo of the superiority of his vessel to Porfirio’s. But Porfirio had the engineer’s signed promise to use his equipment, and he demanded that it at least be tested. In the coming weeks, Benítez Rexach submitted the Tenth of February to trials but sabotaged them at every turn: He claimed that the dredge wouldn’t function properly in the tropical weather; he insisted that it first be tried in the most ill-suited portion of the harbor; he whispered to Trujillo that its gas-powered engine might ignite and blow up the whole port.

Porfirio, suffering one of his father-in-law’s periodic silent treatments, couldn’t get a hearing. He could see that he was being shut out of the operation, and he was realistic enough to wish only to recoup the lease money he’d been promised so as to repay Trujillo for the dredge. Even that much Benítez Rexach refused, and so Porfirio took decisive action. In his full captain’s uniform, complete with sidearms, he rode a launch out to the work site in the harbor and accosted the engineer. “I leapt at him, grabbed him by the collar and shook him like a carpet,” Porfirio remembered. “‘Thief! If you continue waging war against me and don’t pay me right now what you owe me, I will destroy you!’ He was terrified. He collapsed. He promised everything I wanted.”

But as soon as Porfirio left, Benítez Rexach raced to tell Trujillo that he would have to quit working on the harbor improvements for fear that Porfirio would kill him. Trujillo offered reassurance: “Four officers of my guard will accompany you and let Captain Rubirosa know what it will cost him if he touches one hair on your head.” The operation continued without further hindrance while the Tenth of February sat unused and worthless. As a Dominican businessman—indeed, as a Dominican man—Porfirio was toast.

It would be hard to imagine a worse fall: from golden aide-de-camp to anointed heir to broke, disgraced nonperson in less than three years. With whatever money they could scrounge, Porfirio and Flor decided to leave the country and look for less dreary prospects in the United States. In the winter of 1934–35, they moved to New York City. Trujillo, perhaps to let them tumble further into his debt, let them go.

This was, in most ways, madness. In Ciudad Trujillo, even on the outs with the Benefactor, they had connections, prestige, resources. In New York, for which they didn’t even have the proper winter clothing, they were broke, they didn’t speak the language, and they were anonymous refugees living in a cheap Broadway hotel and, later, in Greenwich Village, where at least one associate would later remember Porfirio working, briefly, as a waiter.

“It was a nightmare,” Flor remembered. Her husband, as he had back home, “disappeared to play poker with Cuban gangster types while I waited in that dingy hotel room, watching the Broadway signs blink on and off.”

There was no money: “When he won, we ate; when he lost, we starved.”

And he had other interests: “He would come home at 6 a.m., his pockets stuffed with matchbooks scribbled with the phone numbers of women.”

They fought: “Angry, brutal, he shoved and hit me when we argued.”

It was utterly foolish to think of New York as a going prospect. They could count on no help from the consulate, which obviously answered to her father. There was a Dominican presence in the Latin American community in the north of Manhattan, but most of that contingent was made up of people who had fled Trujillo and were actively plotting his replacement—again, a dead end. The only significant contact they had was a mixture of comedy and menace: three cousins of Porfirio’s, sons of Don Pedro’s sister, who had been raised in the city since boyhood and had spent most of their grown years engaged in petty crime and worse. “When I saw ‘West Side Story’ I was reminded of them,” Flor recalled. “Good-for-nothings who had never worked.”

Among them was Luis de la Fuente Rubirosa, aka Chichi, who had been in trouble with the law since boyhood. In 1925, he had been arrested for burglary and sentenced to a spell at the New York Reformatory for Boys. In 1932, he was tried for assault and robbery and acquitted. He was short, maybe five-foot-six, with jug ears and a pinched face and sharp cheekbones, a wiry, dangerous little creep, plain and simple, with nothing to offer his cousin and his wife in the way of truly promising possibilities.

New York was coming to seem even more disastrous than Ciudad Trujillo. And then the most unexpected lifeline appeared: a telegram from the Benefactor announcing that Porfirio had been elected—elected!—to the national congress and that both he and Flor were required back home. Unable to explain what was happening, they were equally unable to resist.

Trujillo’s congress was a dog-and-pony show that fooled no one. The deputies were required upon taking office to submit signed and undated letters of resignation so that the president could remove them at any time for any cause; it wasn’t unusual for a man to return from lunch to attend the afternoon session only to find out that he had, without knowing it, quit his post during the recess. And when they did sit, the legislators were utterly impotent. “In every session,” Porfirio remembered, “the President read aloud a proposed law and we adopted it with a show of hands. There was never any question of discussing it.”

A nation conditioned by centuries of rebellion and despotism wasn’t especially outraged by this pantomime of a government. And Trujillo was modernizing the Dominican Republic in a way that no previous tyrant had: paying off its staggering national debt to the United States, paving roads, building an electrical grid, and so forth. Soon after he took power, the island suffered a devastating hurricane that virtually bowled it back to the Stone Age; the speed of repairs and, indeed, improvements under Trujillo’s firm hand made him a hero in the eyes of his countrymen.

As a result, Trujillo had no shortage of stooges who could fill the seats of this cardboard congress, so it wasn’t at all clear to Porfirio why he was so urgently needed. But in April 1935, he was called in to see the president—who suddenly seemed very happy to see his son-in-law—and given a delicate assignment. When he got home, he told Flor that he would be going back to New York the next day on official business.

On April 16, Porfirio disembarked from the S.S. Camao in New York and checked into the St. Moritz Hotel on Central Park South. Along with his personal effects, he had a suitcase containing $7,000 in cash.* A few days later, he toted that suitcase to the Dominican consulate on Fifth Avenue, where he met with a small group that included his cousin Chichi. On April 27, he left for Miami; from there he sailed for San Pedro de Macorís, his spare suitcase filled this time with new dresses and other gifts for Flor.

The following day, a Sunday, a group of Dominican dissidents met in Manhattan to discuss their plans for unseating Trujillo. Among them was Dr. Angel Morales, the most recognized Dominican statesman in the world. In the years before Trujillo’s assumption of power, Morales had served his country as minister of the interior, minister of foreign affairs, minister to Italy, minister to France (he was once Don Pedro Rubirosa’s boss), and minister to the United States. In the mid-1920s, he had been elected vice president of the League of Nations. In 1930, he had run in the rigged election that gave Trujillo the presidency; when he lost, he fled to New York for his life and was declared a traitor; all his property in the Dominican Republic was confiscated by the new government.

As an alternative to Trujillo, Morales had supporters not only in the Dominican exile community but in the U.S. government and among private parties in North America who sought to foster change in the island nation. But he so feared Trujillo’s ruthlessness and reach that he lived in New York like a hunted man. He shared a Manhattan rooming house flat with Sergio Bencosme, a general’s son who had served Trujillo’s rivals as a congressional deputy and minister of defense. The two lived on the proceeds from a small coffee importing business. And they tiptoed around the city in mortal trepidation: Morales was said to be hesitant to eat anywhere save at his landlady’s table for fear of being poisoned or attacked.

His fears were justified that Sunday night. When the dissident meeting broke up, Morales, in a rare feeling of well-being, went to dine out with friends. Bencosme returned to their apartment on the seventh floor of a Washington Heights walk-up and a supper cooked by Mrs. Carmen Higgs, their thirty-year-old Latina landlady.

At about 8 P.M., there was a knock at the door. Mrs. Higgs, who shared her lodgers’ fears, asked who was there.

“Open this door,” came the harsh reply.

She cracked the door to have a look, and a short, wiry man in a brown suit and brown hat pushed in past her, brandishing a .45 caliber pistol. Mrs. Higgs screamed and leapt back into the kitchen; fearing a robbery, she removed her engagement ring and wedding band and tossed them into a coffeepot that was percolating on the stove. The gunman looked into the kitchen and then moved down the hall, first into the living room and then into an adjoining bedroom.

Bencosme, shaving for dinner, his face covered in lather, heard the commotion, came toward the front door, and peered into the living room. Finding it empty, he went on to the kitchen to see what the screaming was about. From the rear of the apartment came a shout—“Die, Morales!”—and two shots struck Bencosme in the back; the bullets passed through his body and lodged in a bureau. The gunman ran through the hall—over the body and past Mrs. Higgs—and down the six flights of stairs into the street. Bencosme, staggering and in agony, made his way to the apartment of a neighbor who had a telephone and rang for help.

When police and ambulance drivers arrived, they couldn’t at first make out what happened. Mrs. Higgs was so frightened that she couldn’t bring forth any English and insisted that she’d been robbed until a detective found her jewelry brewing with the coffee. Bencosme, barely conscious by the time he was taken off to Knickerbocker Hospital, muttered that he was a political refugee. Only when Morales returned home at midnight to find the chaotic scene did a reasonable theory of the case emerge: Somebody had tried to kill him and had mistakenly shot Bencosme.

On Monday, forty known Trujillo supporters from among Manhattan’s Dominican community were rounded up and questioned by detectives of the so-called alien squad at the West 152nd Street station, but no arrests were made. On Tuesday morning, Bencosme succumbed to his wounds and died in the hospital, leaving behind a widow and two children in Ciudad Trujillo. Finally, Mrs. Higgs sat in a station house and looked at mug shots of Dominicans with histories of criminal violence. She looked at a 1932 booking photo and declared that the man pictured in it was the killer.

It was, of course, Chichi de la Fuente Rubirosa.

After going before a grand jury to present the known facts of the case, many of which derived from Morales’s own contacts and investigation, the New York County District Attorney’s Office filed an indictment in absentia for murder against Chichi on February 18, 1936. According to the charges, “Captain Porfirio Rubirosa” had been in New York immediately prior to the shooting and Chichi was, nearly a year after the shooting, living in Ciudad Trujillo as a lieutenant in the Dominican army despite his total lack of military training. Chichi’s extradition was sought through the State Department, but little hope was held out that the accused killer would be sent back to New York.

Back in Ciudad Trujillo, Flor knew nothing about the events in New York—the murder wasn’t exactly front-page news in the state-controlled local papers—but like everyone else in the culture of gossip that was coming to thrive under Trujillo, she heard things. She was only mildly surprised, therefore, to answer a knock at her door on a night when her husband and father were out of town to find Chichi standing there begging for help.

“I had to leave the States,” he explained. “They are pursuing me.”

For a while, Chichi lived with his cousin and his wife and sought work around the city; he even put in a spell on the harbor project that had driven Porfirio and Flor to leave home the year before. It wasn’t a promising situation, and Porfirio didn’t exactly relish it, especially as Chichi aggravated matters by hinting broadly around town that he had done Trujillo a great service and deserved to be at least a captain for his efforts.

He might as well have cut his own throat. “One evening,” Flor recalled, “we came home to find him gone. Servants said ‘strangers’ had surrounded the house and taken him away. We never heard from Chichi or saw him again—and my husband would not comment on the affair.” (When a year or so later Flor thought she saw Chichi on the street and pointed the look-alike out to Porfirio, he snapped back, “Don’t mention that name! Those kids were good-for-nothings!”) When the U.S. State Department inquired as to Chichi’s whereabouts, they were told alternately that no such person existed and that the fellow in question had died in a dredging accident in the harbor. But police and prosecutors in New York still wanted to talk to Porfirio—and they would be patient in waiting to do so for decades.

This drama did little to stabilize the marriage of Porfirio and Flor, which continued to be roiled by Trujillo. In the summer of 1935, they found themselves once again in the Benefactor’s confidence. He was suffering from a severe case of urethritis and required surgery. Because of his need to maintain a show of superhuman capacity, he arranged for a French specialist to be brought secretly to perform the operation. The doctor was put up—again, on the QT—at Porfirio and Flor’s home, where he conducted three operations on the president, using only local anesthetic. Trujillo was so weakened by the ordeal that rumors spread as far as Washington, D.C., that he was dying. To put an end to the gossip, he left his makeshift intensive care bed and had himself driven through the capital in a Rolls-Royce for an hour, long enough so that word of his good health would circulate. When he recovered, he returned to his own house without so much as a thank-you for his daughter and son-in-law.

At the time, Flor’s own health was of concern. She had been trying to conceive a child and was told by her physician to seek the advice of a specialist in the United States, where she underwent a surgical procedure designed to address her infertility.* When she came home hopeful of starting a family, she found her household had been the scene of one of Porfirio’s bacchanalian parrandas: There were women’s earrings in the swimming pool, and one of her servants confided that “all the whores in Santo Domingo have been here.”

She begged her father to help her do something about this nightmare, and he offered a unique solution: In July 1936, he named Porfirio secretary of the Dominican legation in Berlin.

They arrived at the height of preparations for the Nazi Olympics, an event that drew to the city a claque of idle rich scenesters from around the Continent: Porfirio’s crowd exactly. With almost no work assigned to him, he kept up the equestrian skills in the city’s parks, began to take a series of fencing lessons, and, in general, dove into a more luxe version of the life he had lived in Paris as a feckless teen. “Berlin suited me perfectly,” he admitted blithely. “I could ride, go to clubs, drive fast and dance at the afternoon teas at the Eden.”

Needless to say, those afternoon teas involved women—and not Dominican whores, either, but a breed of woman that intimidated Flor. “How could I,” she wondered, “still a provincial girl in her early 20s, unworldly, badly dressed, mousy, compete with these women?” She was particularly anxious about a certain Martha: “Soignée, blazing with diamonds, she was everything I was not.”

But there were other, nameless rivals. There was the time one of Porfirio’s afternoon teas turned into dinner and an overnight stay. He snuck home to the Dominican embassy at dawn, quickly showered and dressed for breakfast, and made his way to his dining room where Flor and the ambassador, among others, awaited him. He sat nonchalantly and then noticed a bouquet of roses in front of his place setting. Attached was a note written in a feminine hand, a paean to a night that had seemed never to end, like midsummer’s eve in Sweden. Whatever cock-and-bull story Porfirio had planned to offer vanished from his head: “My pretty German spoke of the Scandinavian summer. Breakfast proceeded like the middle of the Siberian winter. Since then, I can’t see a bouquet of roses without feeling a bit of a shiver.” But any chastening he felt soon dissolved, as when he had frightened his parents by spending the night out as a boy, and he presently resumed his rambles.

Official duties dotted the high life. Because of their relative worldliness, because they were relatives of the Dominican president, and because the Third Reich was courting Caribbean governments as part of its scheme of global expansion, Porfirio and Flor were granted a number of remarkable privileges. When the Olympics began, they were permitted to sit in Hitler’s box at the main stadium, where they observed the Führer’s caroms between childish glee at each German victory and rock stolidity when another nation’s anthem was played at a medal ceremony. They were feted by Hermann Göring, who took Porfirio aside during the evening and expressed interest in obtaining a particularly handsome Dominican medal. They were invited to the annual party rally in Nuremberg, where they gazed in stupefaction at an orgy of adulation on a scale of which Trujillo, with his own budding cult of personality, could only dream.

Despite such impressive shows, both young Dominicans were shocked by the outright anti-Semitism of the regime. Flor found herself secretly aiding a Jewish girl who had been her schoolmate in France, obtaining visas for her and her husband and seeing to their getting settled in the Dominican Republic and started in the tobacco business. Porfirio was staggered one day as he rode through a park and saw a young man wearing a yellow star and being humiliated by Germans. “Racism never occurred to me,” he reflected. Indeed, he had enjoyed a certain éclat for his Creole heritage, which was evident even though he was fair-skinned enough to pass for Latin as opposed to Negro. “In the Dominican Republic, blacks and whites were equals. At times they mixed. There were social differences, but in the most exclusive places one met people of color. In Paris as well, racial problems didn’t exist.”