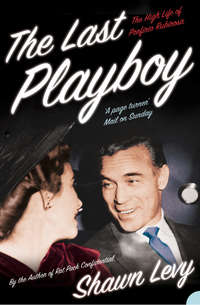

The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa

But at the same time, neither of them had any inkling of how truly invidious the Reich was or would be. Dazzled, perhaps, by his good fortune to be living with money in a posh European capital, Porfirio reckoned that Hitler’s great shows of force “were no more than a bluff.” In retrospect he would feel some shame at his miscalculation. “I’m not a politician,” he would explain. But he noted, too, that the diplomatic corps of larger and more sophisticated nations were equally gulled by the Führer. If he had been fooled, he wasn’t alone.

Before he could fathom the truth of the Reich, however, he found himself transferred. Flor was so miserable living in Berlin with her rakish husband that she wrote to her father to express her displeasure:

I have learned a little German and seen a lot of the country, and I have admired the great work of Hitler. But nevertheless I’m not happy.… In diplomatic circles, most of the officials are on the left. They don’t invite us to their dances and I don’t have the chance to meet anybody. If it isn’t too much to ask, I’d like you to transfer us to Paris.… There, I’d have occasion to attend many conferences and get to know better the French literature that I like so well. Please let me know if you can comply with this request.

Indeed, he could, but first a royal interlude in London: On May 12, 1937, they represented the Dominican Republic at the coronation of George VI; Porfirio met the monarch in a private audience. Two days later, at the Dominican legation at 21 Avenue de Messine in Paris, the following note arrived from the undersecretary of foreign relations in Ciudad Trujillo:

It pleases me to inform you that the most excellent Señor Presidente of the Republic has seen fit to name Mr. Porfirio Rubirosa as Secretary First Class of this legation in substitute for Gustavo J. Henriquez, who has been designated Secretary First Class in Berlin in substitution for Mr. Porfirio Rubirosa.

This was far more like it.

Paris had changed in the decade since he’d last lived there: The tangos and Dixieland in the nightclubs had been swept away by a wave of Russian music and Gypsy-flavored hot jazz; the chic hot spots were now on the Left Bank of the Seine instead of the Right. But it was intoxicating to be there, to saunter into his old haunts in search of old friends, to pass by the erstwhile family house on Avenue Mac-Mahon, to delight in the new fashions favored by women in both couture and amour. When he stowed away on the Carimare and left France he was a child, as Don Pedro had despairingly declared; now he was a twenty-eight-year-old man with means and liberty.

“As soon as I arrived in Paris,” he remembered without shame, “invitations began pouring in. I was out every night, often alone. My wife objected … she could not keep up with me.”

In large part, his duties at the embassy would be, as in Berlin, ceremonial. He and Flor were presented to the general commissioner of the upcoming Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, and he found himself appointed to a panel of judges who would award prizes to various exhibits. It was a prestigious post. The exposition, a gigantic world’s fair celebrating global modernity, took over the area around the Eiffel Tower and Palais de Trocadero throughout the summer. It was a marvel of aesthetic novelties paraded by nations on the verge of global war: Albert Speer’s soaring German pavilion; Pablo Picasso’s searing Guernica in the Spanish pavilion; a Finnish hall designed by Alvar Aalto; illuminated fountains; exhibitions dedicated to the latest advances in refrigeration and neon light. The Dominican Republic couldn’t compete with those sorts of things, but they did share some exhibit space with other Caribbean nations, showing off native crafts and the work of the latest Dominican artists. Trujillo instigated dozens of letters between Paris and Ciudad Trujillo about the exposition; he was delighted to learn that the French artist and critic Alfred Lebrun “had formed an elevated new idea of the progress achieved by our country,” and he sent the eminent man a box of cigars in gratitude.

The Benefactor lived for this sort of thing, and he kept Porfirio busy with the most bizarre little requests to satisfy better his comprehension of the modern world and his nation’s place in it. He sent to Paris for atlases and diplomatic dictionaries; he hired a Paris-based Caribbean journalist to analyze the possibility of his being awarded a Nobel Peace Prize; he had framed photos of the legation sent to him, and signatures of foreign officials, with whom he also exchanged pens; relishing the opportunity to acquire foreign honors in exchange for those of the Dominican Republic, he ordered miniatures and reproductions of each new award he received. Porfirio served so well as the conduit for all this ephemera that he was promoted to consul in July 1937.

But at the same time that he put forward the shiny front of his daughter and son-in-law for Europe’s leaders, Trujillo was revealing his most atrociously dark side back home. He had spent the first years of his rule quelling—through political machination, bribery, and, especially, brute force—all internal opposition. Now he turned his attention to Haiti. It was a natural target for him: The border between the two countries was something of a fiction, having been drawn along no clear geographical or political lines and passing through remote districts whose residents truly might not be able to say which country they lived in or who its ruler was. Moreover, Trujillo, like every Dominican, had been bred with a fear and hatred of Haiti born of centuries of conflict, and he had, like every leader of both nations, harbored dreams of uniting Hispaniola under his hand. At the very least, he wanted clear autonomy over his own portion of the island, and Haiti and its citizens always seemed to be interfering with that prospect. Throughout the early years of Trujillo’s reign, Haitian encroachment on Dominican territory became burdensome in a number of ways: public health, cattle rustling, an increase in churches practicing a mixture of Catholicism and voodoo, Haitian infiltration into the Dominican sugar industry, and so forth. There had been some efforts toward a détente between Trujillo and his Haitian counterpart, Stenio Vincent. But as the grievances were felt chiefly by Dominicans, it was inevitably Trujillo who was the more vexed.

His frustration reached the tipping point in October 1937, when he gave a provocative speech about Dominican sovereignty and national purity. That very night, up and down the border and in the areas farther inland that were easily accessible to Haitian migrants, small cadres of armed men—some from the official military, others no better organized than the makeshift platoons that Don Pedro Rubirosa had once commanded—rounded up all the Haitians they could find and slaughtered them.

It was the most brutal sort of genocide. In a land where virtually everyone was of mixed blood, it was nevertheless assumed that Haitians were generally darker-skinned, meaning that many black Dominicans were swept up in the raids; a crude test of certain Spanish words that French speakers notoriously had trouble pronouncing was instituted. Have a dark enough complexion and say perejil (“parsley”) improperly and you were dead. It went on for several days: mass murder by machete and pistol. By the time it was over, some 15,000 to 20,000 people had been killed.

It took several weeks for word of the massacre to reach the outside world, and when it did, the bloody face of the Trujillo regime first became known globally. In France, the colonial fatherland of Haiti, the events were received with special outrage; Trujillo took out subscriptions to French newspapers to keep track of what they were saying about him. For some time, Trujillo managed to keep the world at bay by explaining the genocide as a spontaneous outburst of his people, who had grown tired of being inundated with and exploited by Haitians. That charade didn’t last long—the United States government, still keenly observing Dominican affairs, was particularly anxious to uncover the truth—and Trujillo finally submitted to mediation and a judgment against his government, which paid $525,000 in damages to Haiti. The reaction of the world to this ghastly event forever altered Trujillo’s political prospects. He had forced his way to the presidency in 1930; he had run unopposed for reelection four years later; but after the Haitian massacre he could never again hold the office, satisfying himself rather with strictly managing Dominican political and economic life through a string of puppet presidents he installed in the National Palace. As a sop, he had himself declared generalissimo, adding an unprecedented fifth star to his epaulets and another title to the encomia by which he demanded to be addressed.

While Trujillo was roiled by grisly events of his own making, his son-in-law prospered in small fashion. In August 1937, as the barbaric Haitian plot was forming, a letter arrived at the Foreign Ministry in Ciudad Trujillo from a stamp collector in Paris: He had seen in the collections of several local dealers whole sheets of uncanceled Dominican stamps and was wondering if he might buy such rarities directly from the source and avoid paying a markup to middlemen. Trujillo immediately wrote to the Parisian embassy notifying the ambassador that somebody in his charge was stealing stamps and selling them on the sly to philatelists around the city. After several weeks, a reply was sent declaring that the dealers had identified their source for this contraband as Porfirio’s brother-in-law, Gilberto Sánchez Lustrino, who had, in the way of things in the Trujillo Era, turned from snobbish disparagement of the Benefactor’s mean roots to groveling obsequy and parasitic dependence. In the coming years, Sánchez Lustrino would paint sycophantic word pictures of the Benefactor’s greatness in prose and verse, and as editor of the ardently proregime newspaper La Nación. In Paris, one of several foreign postings in which he would serve, he had obviously fallen in with Porfirio, whose delicate fingerprints would be invisible on this clever but short-lived enrichment scheme. In any case, no record of punishment for the thefts found its way into the diplomatic archives.

Perhaps Porfirio wasn’t guilty. But more likely his complicity was overlooked by the ambassador himself, the Benefactor’s older brother Virgilio Trujillo Molina, who would fill ambassadorial posts in Europe for decades. Virgilio was always frankly resentful of his younger brother, if for no other reason than the mere notion that he was older and yet less powerful. Dependent on his sibling, like all other Dominicans, for work, money, and even life and limb, he made a habit of cultivating his own cadre of acolytes and, on occasion, hatching his own financial and political intrigues. Virgilio found a sufficiently eager ally in Porfirio, for instance, that he overlooked the younger man’s infidelities against Flor, who was, after all, his niece. And he would continue to maintain friendly relations with Porfirio as the illustrious marriage of 1932 devolved into the domestic shambles of 1937.

Paris, alas, hadn’t, as Flor had hoped, proved an even ground where her familiarity with the surroundings would counterbalance her husband’s shamelessness. The couple had moved from the embassy to a home in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a suburb just beyond the Bois de Boulogne. It should have been heaven. But, “unfortunately,” in Porfirio’s view, they were not alone: “A cousin of Flor’s was with us constantly.” The girl was Ligia Ruiz Trujillo de Berges, the daughter of the Benefactor’s younger sister Japonesa (so nicknamed for the almond shape of her eyes). “When I went to the embassy,” Porfirio recalled, “she didn’t separate from Flor for even a minute; in the evenings, she went out with us. She was in all our conversations, even our arguments, and this is no good for a couple. It’s possible to convince a woman of your good intentions or of the meaninglessness of a little fight; but two!”

Ligia had Flor’s ear and convinced her cousin that the marriage had degenerated irredeemably. She persuaded Flor to return to Ciudad Trujillo to seek her father’s help in corralling Porfirio and perhaps in making him feel sufficiently jealous or guilty or nostalgic that he would change his ways. Flor explained the trip by claiming that her father wanted her back home because of some family crisis (“She lied,” Porfirio declared with misplaced umbrage) and left France. When she arrived back home, she sent word of her true intent. “I feel life between us has become impossible,” he reported her to have said. “I want to see if I can live without you.” Then, he claimed, she visited his mother, Doña Ana, to solicit her help in repairing the marriage. Per Porfirio’s account, Flor sobbed to her mother-in-law, “Ask him to come find me. I love him. I know I’ve always loved him. Ask him to forgive me. Everything can go back to how it was.” Doña Ana, taking pity, relayed as much to her son.

But, he said, he balked. “Everything couldn’t be as it was. Nothing could ever be as it was. It’s true I erred as a husband, but there’s no doubt that I regretted this match. In the lives of men, as in the histories of nations, there are periods of acceleration, and I was living through one. The brake that Flor represented no longer worked. My mother’s letter didn’t move me.”

Naturally, Flor’s account of their separation would be different. The parent at whom she threw herself in her version of events was her own father, who coldly declared that he’d warned her about marrying such a wastrel and tried to mollify her with this consolation: “Don’t worry, you’re the one with money.” As proof, he tossed her a catalog of American luxury cars and told her she could choose one for herself; she picked a fancy Buick and tried to have it sent to Paris as a gift to Porfirio, hoping it would mend the breach; her father put a stop to that plan.

Indeed, not only wouldn’t Trujillo allow a car to be sent to his son-in-law, he wouldn’t allow his daughter to return to him. “I’ll never let you go back to that man,” he announced, and he had his lawyer begin writing up the papers necessary for a divorce.*

Flor claimed that the shadow of divorce evoked a new passion in her husband: “When I wrote that I wasn’t coming back, he sent letters pleading with me to return, threatening to join the French Foreign Legion if I didn’t.”

But Porfirio had a slightly different recollection of his impending bachelorhood: “Freedom in Paris was never disagreeable. I went out a lot.”

In November 1937, the decree was declared; in January 1938, the couple were officially divorced. Separated from Trujillo’s wrath by an ocean, protected by Virgilio and, perhaps, by his ability to implicate the Benefactor in the Bencosme affair, connected more to Paris than he was to his own homeland, Porfirio stayed put, chary but more or less safe and even eager. Having married the boss’s daughter and returned in luxe fashion to the city of his boyhood ramblings, he was ready to take huge gulps of the world.

* Figure $100,000 in 2005.

* The question of who was to blame for the couple’s childlessness would never be answered. Neither ever had children, despite the combined twelve marriages they entered after this first. It was long rumored that Porfirio was rendered sterile by a childhood bout with the mumps, and Flor occasionally hinted that one or both of them had been rendered infertile by a venereal disease Porfirio had contracted in one of his rambles and subsequently shared with her.

* Just the year before, Trujillo had passed a remarkably progressive divorce law that allowed a marriage that hadn’t produced children after five years to be dissolved by mutual consent of the spouses. It was a means for him to leave Doña Bienvenida, with whom he had no children, and marry María Martínez, the mother of Ramfis. Not long after he pulled off this legislative coup and took his third wife, however, he fathered a child—technically a bastard—with his just-divorced second wife.

FIVE

STAR POWER

On the one hand: liberty.

In divorcing Flor, Porfirio had unchained himself from an anchor, but he had also let go of a lifeline.

Yes, she behaved prematurely like an old Dominican dama with her petulant whining about his carousing and his other women, refusing to accept him for the type of man he was.

But: As the daughter of a powerful man, she was a direct conduit to money, security, and stature—and perhaps, given Trujillo’s incendiary nature, life itself. Losing her meant unmooring himself totally from the life he’d known since boyhood, a life implicated in the political goings-on of his homeland.

He lost everything. Before long, dunning letters began arriving at the Dominican embassy in Paris—saddleries and purveyors of equestrian clothing looking for payment on items he’d bought with a line of credit he no longer commanded.

By then, at any rate, he was no longer, technically, an embassy employee. Trujillo had expelled him from the diplomatic corps in January 1938. Virgilio, the generalissimo’s resentful older brother, managed to secure him a temporary appointment as consul to a legation that served Holland and Belgium jointly, but that expired by April. He held on to his diplomatic passport and was occasionally seen around Paris in embassy cars, but he was, literally, a man without a country. He wasn’t about to go home to the Dominican Republic, where his prospects for work were no better than in Europe and his prospects for play considerably worse. Plus, he had already heard from his mother not to risk the trip: Trujillo wanted his head; Paris was decidedly safer.

He was certain in his own mind that Flor hadn’t instigated her father’s fury. Indeed, he would declare that he always harbored warm feelings for her: “After this romantic catastrophe, we stayed good friends.” (They were widely said, in fact, to reignite their sex life whenever Flor, who’d apparently overcome her initial aversion to his lovemaking, was in Europe.) “And,” he continued, “I followed, with friendship, her life.” With friendship and, no doubt, amazement: after divorcing Porfirio, Flor would go on to take another eight husbands, including a Dominican doctor, an American doctor, a Brazilian mining baron, an American Air Force officer, a French perfumer, a Dominican singer, and a Cuban fashion designer. She had a short heyday as a diplomat in Washington, D.C., but during long periods of her life her father disowned her and even had her held under house arrest in Ciudad Trujillo. She would eventually come to dismiss her first husband with a shrug, answering interviewers who asked whether he was handsome or charming with a curt “For a Dominican.”*

And so what to do?

Another man might assess the situation and reckon it was time to think about settling down in France: a wife, a job, kids, a house, responsibility.

Not a tíguere, not with this sort of freedom, not at this time, in this place, with this thrilling sense of possibility and a titillating sense of impending catastrophe. “I was a young man in a Paris that the specter of war had heated up,” he remembered. “I lived a swirling life, without cease, without the pauses that would have allowed me the chance to think and make me realize that giant steps aren’t the only strides that suit a man.”

He spent time at Jimmy’s, a Montparnasse nightclub run by an Italian whose real name too closely resembled Mussolini’s to make for good advertising and who therefore took an American name as a PR maneuver. There, the comic jazz singer Henri Salvador became a friend. Porfirio sat in with his band for late night sessions—his little skill on the guitar and enthusiasm for drums were fondly received—and led parrandas of the musicians and clubgoers late into the night, retiring to this or that partyer’s flat for bouts of drinking and merrymaking that could last until the middle of the next day.

Of course, this sort of traveling circus required funding, and, as its ringmaster no longer enjoyed legitimate work as a diplomat, other strategies emerged. There was the familiar one of living off a woman. La Môme Moineau, the singing, yachting wife of Félix Benítez Rexach, was in Paris and available to him once again as her husband was off earning millions on his various projects in the Dominican Republic. Now, however, she had a fortune to spend on and share with her lover; he drove around the city at various times in one or another of her little fleet of luxury cars; occasionally, he would raise cash by selling off some valuable bijou from her jewel case.

This character—nightclubber, cuckolder, kept man, gigolo, scene maker, skirt chaser, dandy—was not so much a new Porfirio as an evolved one. Nearing thirty, freed of father, wife, and father-in-law—the living connections to his homeland that had thus far defined him—he was no longer an exotic, a Dominican in Paris, but, more and more, a Parisian with intriguingly Dominican roots. He had been an enthusiastic regular in the demimonde; now he was a staple of it. And, free of the constraints of decorum that adhered to him as the son of Don Pedro or the son-in-law of Trujillo, he no longer required so formal and elaborate a name as Porfirio Rubirosa. Anyone who knew him, truly knew him, in Paris after his divorce or, indeed, for the rest of his life, knew him as Rubi. Even more than his mellifluous given name, which he still used to dramatic effect and for official purposes, this new moniker captured his mature essence: the jauntiness, the rarity and high cost, the sparkle and the sharpness and sensuality and the bloody, cardinal allure.

Especially, perhaps, the bloody allure.

Over the years, he would—by virtue of his high living, his obscure origins, his association with Trujillo, his love of thrills and danger—almost inevitably be associated with shadowy events. Most of it was idle gossip. In some cases, such as the Bencosme murder, there were real reasons to think he was involved, albeit peripherally.

And then there was the matter of the Aldao jewels and Johnny Kohane.

For all the munificence of La Môme Moineau, Rubi wasn’t satisfied with his solvency. The life to which he aspired required real capital. He needed a score. In early 1938, while he was still holding, despite Trujillo’s injunctions against him, a diplomatic passport and temporary consular position, Rubi became involved in a scheme to smuggle a small fortune in jewels out of Spain. The goods in question belonged to Manuel Fernandez Aldao, proprietor of one of the most esteemed jewelry establishments of Madrid. In November 1936, when the Spanish Civil War had so turned that Madrid was under siege, Aldao had fled for safety to France and left a good deal of his wealth behind in the form of a safe filled with jewels guarded by an employee named Viega. Two years later, Aldao had need of his resources but was unable to retrieve them himself. He came into contact with Rubi, perhaps through Virgilio Trujillo, and hired him to go to Madrid and use his diplomatic pouch to transport a cache of jewels—and an inventory describing them—back to Paris.

In the time it took for the details of the operation to be worked out, another errand was added to Rubi’s schedule and another conspirator to the plot: Johnny Kohane, a Polish Jew who had also fled Spain without his fortune (some $160,000 in gold, jewels, and currency, he said), was introduced to Rubirosa by Salvador Paradas, who’d replaced him at the Dominican embassy. Kohane had need of his stash, and it was agreed that he would join Rubi on the trip using a passport borrowed from the Dominican embassy chauffeur, Hubencio Matos. In February, the two would-be smugglers got into the embassy’s Mercedes and drove across southern France and, through the Republican-controlled entry point of Cerbere-Portbou, into war-ravaged Spain.

A dozen days later, Rubi returned—alone.

He handed a sack of jewels over to Aldao—a smaller one than the Spaniard expected—and claimed that he’d never been given any inventory to go with it. And he told a hair-raising story about the bad luck he and Kohane had run into outside of Madrid when they were off fetching the Pole’s fortune. They were set upon, he said, by armed men, he wasn’t sure from which side, who chased them and shot at them, killing Kohane. He was lucky, he said, to get out of there with his own skin intact.