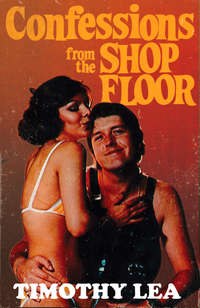

Confessions from the Shop Floor

Confessions from the Shop Floor

BY TIMOTHY LEA

Contents

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

‘I’ve answered this advertisement in The Times,” says Sid.

‘The Times?’ A note of surprise enters my voice. My brother-in-law is not exactly what you might call a typical Times reader. He tends to find Exchange and Mart a bit highbrow.

‘Oh yes, Timmo. It’s a very good paper. Excellent foreign section, very sound on the arts — and it takes 10p worth of chips, no trouble.’

I might have guessed. Sid does all his reading off the magazines Mum cuts up to put in the toilet, or what he finds down at the doctor’s when he is trying to get a medical certificate.

‘So what was it about, Sid?’

‘Some geezer wanting capital to extend a profitable business venture.’ Sid takes a reflective sip at his pint and my blood runs cold. Sid’s business brain works with the remorseless speed of a blue glacier and his eye for a good thing is matched only by a rabbit trying to have it away with a bacon slicer. He reads my expression. ‘It can’t do any harm to have a look, can it? I mean, if it’s in The Times it must be all right.’

‘It doesn’t mean it’s all right,’ I say. ‘It just means it doesn’t read dirty. They don’t check everything.’

Frankly, I am amazed that Sid still has any money left. I believe he did all right out of the insurance when Beauty Manor burned down — you read all about that in Confessions from a Health Farm, didn’t you? — but he doesn’t talk about it a lot. Frankly, I am not surprised. Sid’s relationship with Sir Henry Baulkit and Wanda Zonker was confusing and probably very unhealthy and I think that when Wanda disappeared Sir Henry was only too glad to lash out a hefty slice of the insurance money to keep Sid’s mouth shut.

‘What does this bloke do?’ I say.

‘He makes beds,’ says Sid.

‘Domestic help?’ I say. ‘You don’t want to get mixed up in that, Sid. You’ll end up with water on the knee. That’s women’s work.’

‘Manufacturing beds, you berk!’ rasps Sid. ‘Not farting about with hospital corners. Gordon Bennett! Can you see me as a housemaid?’

‘Roll your trousers up and I’ll tell you.’

‘Get stuffed!’ Sid knocks back his drink and shoves the glass towards me agressively. ‘It’s your turn to get them in. I’m not made of money, you know.’

‘Everybody knows that,’ I tell him. ‘They call you Mr Abstinence because you never go for a p.’

‘Piss off!’ Sid always descends to coarseness in the face of superior word power and I take our glasses to the bar and wonder what harebrained scheme he can be considering. The more half-witted it is, the more likelihood there is of Sid parting with some mazuma. I remember Hulapog — the game where you hurled surplus pogo sticks through unwanted hula hoops. He sold four sets. Still, beds doesn’t sound too outlandish. Lots of my best friends have beds. I have passed many a happy hour on them myself. Many people actually sleep on them. Could it be that Sid has actually found a product with a future? I am not sorry to be getting the beers in because — apart from the fact that I am one of nature’s givers — they have a new bird behind the bar who is quite an eyeful. She is of the tinted variety and though not as dark hued as Matilda Ngobla — whose dusky loins I once decorated — she is considerably browner than most brands of toothpaste. She has a lovely pair of top bollocks — slung like cannon balls waiting to be bunged into the breach — and a dark red mouth that makes me think of the texture of rose petals — you can tell I haven’t had my end away for a couple of weeks, can’t you?

‘What is your pleasure?’ she says.

This is the kind of question that can get a few funny answers even though the Highwayman does cater for a nicer class of person these days. Because I think I might get a bit further with a sophisticated approach I resist the easy descent into roguish raillerie and suggest that the consumption of another couple of pints from the wood might go some way towards satisfying my desires.

‘Not many people about,’ I say, gazing down the front of her dress as if I expect to find a pair of feet sticking out from between her knockers.

‘It’s always quiet on a Monday.’

‘I haven’t seen you in here before, have I?’

‘I don’t know. I’m not your eyes.’ While I think about that, she pushes the pints towards me with short jabs of her fingers and gazes into my minces. ‘I help out sometimes when Gladys wants a night off. We probably haven’t overlapped.’ She smiles when she says it like the word ‘overlapped’ means to her what it means to me. ‘32p, please.’

‘And a packet of crisps,’ I say, applying slight pressure to the palm of her mitt as I slide the ackers across. Talk about gentle love play. This is more like the Calmer Sutra than the Kama Sutra.

‘What flavour appeals to you?’

‘Just stick your hand in the tin and see what you come up with.’ She smiles at me and bends over to plunder the cartons of goodies. She has a beautiful bum and a classical case of V.P.L. (Visible Pant Line) showing through her jeans. I go a bundle on that. Any glimpse of underwear always gets percy trying to prize the lid off the counter.

‘Cheese and onion all right?’

‘Favourite. Ta, luv.’

‘That’ll be another 4p, please.’

‘Do you fancy anything yourself?’

She flashes her lashes at me. ‘Not just now, thanks.’

‘See you later, then.’

I return to Sid and slop a gobful of pigs over the table in front of him. ‘Blimey, you’re a clumsy sod, aren’t you?’ he says pleasantly. ‘I never met anyone so bleeding useless when it comes to carrying things.’

It occurs to me to comment that I have been carrying my brother-in-law for years but I restrain myself. Sid’s idea of a heated discussion is trying to shove his fist inside your earhole.

‘Sorry, Sid. I’ll get a cloth,’ I say.

‘Don’t bother. Your handkerchief will do.’ He snatches it out of my pocket and starts mopping up the beer. ‘It’s in a disgusting condition,’ he says. ‘Did you use it for doing an oil change?’

‘My handkerchief? No, I dusted your chair with it.’

Sid leaps to his feet and rubs his german over his here and there like he is trying to touch it up. He is wearing his posh new trousers and is very sensitive.

‘Taking the piss, as usual,’ he says sitting down again and chucking my snitch rag in my lap. ‘You’re a right little bundle of fun, aren’t you?’

I don’t answer because there is no point and the bird behind the bar is giving me the glad eye. Why should one man have so much? It doesn’t seem fair really.

‘Nice bit of stuff, that,’ says Sid.

‘Who? What?’ I say.

‘Don’t play dumb with me! The brown tart. Gordon Bennett! I thought you were going to announce your engagement when you were getting the beers in.’

‘Dad would like that,’ I say.

‘What, the bird or the engagement?’

‘Both. You know what he’s like with those Ngoblas. It’s horrible what goes on in that mind. All that prejudice wrapped up in steaming lust.’

‘Terrible,’ agrees Sid. ‘Your Mum’s the same, isn’t she? She was always terrified that the Ngoblas would start spreading. Do you remember when she thought she heard something in the attic? She thought they were coming through from next door and living there.’

‘Eventually taking over every attic in the street. Yeah, I remember. The chair fell over and she was left hanging, wasn’t she? It gave her lovely long arms, though.’

‘Fred Nadger has had her,’ says Sid.

‘Not Mum!’ I am horrified. I know we live in permissive times and Fred certainly puts it round a bit but —

‘Not your mother! The tart behind the bar. Gawd help us! Can you imagine anyone having a go at your mum?’

When I think about it — which I don’t like doing — I can’t. Not even Dad. Not for years, anyway. The red blood flowing through his veins dried up to a trickle before I could tell the difference between him and Mum.

‘Don’t be coarse, Sid,’ I say. I greet the news about Fred Nadger with mixed feelings. I am glad to hear that the bird does a turn but I am not over enthusiastic about following in Fred’s footsteps — or whatever. I never like to think of other blokes spoiling something beautiful that should be reserved entirely for Timothy.

‘He said she was a right little raver,’ says Sid. ‘She comes from Trinidad. You know, in the West Indies. I reckon they’re all a bit on the jungle bunny side out there. Start rattling your tom toms and the old breasts are thundering up and down against the chests so that you could hammer rivets with them.’

‘Delightful,’ I say. ‘Is Fred all right? Not walking about like an upright concertina?’

‘He looked all right when I saw him,’ says Sid. ‘In the pink, or you might say, in —’

‘Yes,’ I say, heading off Sid’s salty wit before it gets to the pass. ‘I know what you mean.’

Sic takes a long swig from his glass and wipes the back of his hand with his mouth. ‘You know, I like the idea of making things.’ I look at Miss Trinidad polishing a glass and nod. ‘I’d like to play my part in putting this old country of ours back on its feet.’

‘Back on its back, don’t you mean?’ I say. ‘I mean, beds and all that.’

‘Don’t make feeble jokes. I’m serious. Money isn’t everything, you know.’

‘Are you all right, Sid?’ I sniff my pint suspiciously. There must be something in it — there is plenty of room because it isn’t overloaded with hops.

‘It’s this money-grabbing philosophy which is at the root of most of our national ills. Everybody out for number one and devil take the hindmost.’ I can hardly believe my bottles. If Sid helped an old lady across the road she would probably find that she had lost her handbag before they were half way over. Sid must see the expression of incredulity on my mug. ‘Of course, I know that I’ve erred in the past. I’ve been as guilty as anybody when it came to looking after number one. I’ve been overbearing, dictatorial —’

‘Oh no, Sid,’ I interrupt. ‘You haven’t. You’ve been —’

‘Shut up when I’m talking!!’ snaps Sid. ‘What was I saying? Oh yes. I made the mistake of thinking that money was the only thing that mattered. I forgot about the importance of job satisfaction. What’s the point of having a lot of bread if you’re miserable?’

‘What’s the point of being miserable if you’ve got a lot of bread?’ I say.

Sid thinks for a minute. ‘Yeah, well, that’s one way of looking at it, too. But believe me, Timmo. It doesn’t work like that in practice.’

‘I’ve never had the chance to find out,’ I say.

Sid clears his throat. ‘That’s where you’ve been lucky. I’m glad I’ve been able to spare you that. It can be very disillusioning.’

‘Thanks, Sid.’ I now realise why Sid took all the cash from our previous exploits and never paid me anything. He was protecting me from disappointment. What consideration, what humanity, what a load of bleeding rubbish!!

‘I want to put what I’ve learned to some use,’ says Sid plaintively.

The bird behind the bar is standing on a stool to reach down a carton and I nod enthusiastically. ‘Very creditable,’ I say.

‘We’ve worked on both sides of the fence in our time,’ drones Sid. ‘We know the problems. If we can harness management and labour to a common purpose — a purpose not just connected to financial reward — then we can start moving forward again. We can give the whole country a lead. Noggett Beds will set an example to British Industry.’

‘You’re leaping ahead a bit, aren’t you?’ I say. ‘You haven’t even talked to the bloke yet.’

‘That’s my mandate,’ says Sid. ‘You don’t get anywhere these days unless you’ve got a mandate.’

‘I thought a mandate was something you gave to someone else,’ I say.

‘You can give yourself one if you want to,’ says Sid. ‘It’s still a free country — more or less.’

I am pretty certain that neither of us knows what a mandate is so I don’t press the point. The point I would like to press is the blunt job between my legs. Where I would like to press it depends on the trowel behind the bar although I can see one or two likely spots without having to consult Gray’s Anatomy.’ (‘Trowel’ equals a small spade.)

‘Don’t rush into anything. That’s all I ask you,’ I say. ‘If that bloke has to advertise to raise cash there must be something wrong with him. Why won’t the banks lend him the money?’

‘He probably doesn’t want to pay all that interest. I expect he’s offering a better deal. A stake in the company.’ I doubt if Sid would get a stake in the company if they were manufacturing palings but I don’t say anything.

‘Well, watch it. There’s a lot of mean people about.’

‘I’ve met some of them,’ says Sid. ‘The kind of blokes who wouldn’t crash the crisps if they were having tea at Buckingham Palace. Mean, self-seeking people —’

‘All right, all right!’ I say, dropping the packet in his lap. ‘You have these. I’ll get some more.’

I skip to the bar and Miss Trinidad lilts across, shaking her bum like a sulky moggy. ‘What do you want, man?’ she says.

‘Another packet of crisps, please.’

‘Any flavour you have in mind?’

‘The ones you have to bend furthest for.’ I wink at her just to show that I’m joking and it is all good clean fun — well, fun, anyway.

‘Saucy.’ She bends down kicking one leg up behind her and fishes out a packet of crisps between finger and thumb. ‘Plain,’ she says, glancing at the packet.

‘They don’t remind me of you.’

‘Flattery will get you anywhere,’ she says. She is right of course. Be it ever so horrible there is no substitute to laying it on with a shovel. Women do respect sincerity and if you say they look beautiful then they automatically think that you must be sincere.

‘You pack up at closing time, do you?’ I ask, lowering my voice. I can see the guvnor looking at me suspiciously and I don’t want any trouble. I have been told not to come back more times than our next door neighbour’s tom.

‘When we’ve tidied up,’ she says.

‘We might go on somewhere?’ My voice becomes husky and enticing — at least, it tries to.

‘Like where?’ I was afraid she would ask that question. The smarter birds usually do. I was thinking of behind the changing rooms where they store the goal posts but I wanted it to be a surprise — it was certainly a surprise the last time I was there. I had just got this bird pressed up against something solid when all the crossbars fell down and buried her knickers. Very lucky she wasn’t wearing them at the time. It put the kibosh on our romance though. I stepped back a bit sharpish and sat in one of the washing troughs — my trousers were round my ankles, you see. It wouldn’t have mattered but some sloppy bastard hadn’t bothered to take the plug out. Talk about a passion killer. It wasn’t all that warm to start off with.

‘I could take you home,’ I say.

‘What, to your place?’ This had not been my intention but the hint of interest in her voice makes me think again. Mum and Dad usually go out less often than the tide in the Mediterranean but some mate of Dad’s at the lost property office — where Dad works and furnishes our home — has got him involved in a rotarian’s ladies’ night. Of course, Dad didn’t want to go but Mum nagged him rigid. She said the last time Dad took her out was to see ‘Brief Encounter’ — they didn’t get in because there was a queue — and thirty years later she feels like hitting the high spots again. Dad groans and moans about the cost of the tickets — especially when he finds that the cost of what he thought was a double is for a single and that wine is not included — but Mum gets her way in the end. ‘Don’t worry about the wine,’ she says wittily. ‘I’ve had enough whining from you to last me a lifetime.’

I seem to recall that the tickets said ‘Carriages 2 am’ — Dad thought it meant real carriages, stupid old git — so my esteemed parents should be out of the way long enough for me to cement a meaningful relationship and be snug in my cot by the time they lumber through the front door.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘Come back for a drink.’

‘Oh,’ she says. ‘That will make a change.’ I think she is trying to be sarcastic but I don’t take her up on it.

‘I can run you home afterwards,’ I say. That is literally correct. Provided I am still capable of running I will be quite willing to lope beside the young lady as she leaves the purlieus of Scraggs Lane, from time immemorial and immortal the home of the Leas. If she is expecting a car she will be disappointed.

‘All right,’ she says. ‘But I won’t be able to stay long.’ I have to suppress a smile. They all say that. It is like turkeys making plans to visit the in-laws on Boxing Day.

‘How did you get on?’ says Sid when I sit down again.

‘Salt and vinegar,’ I say. ‘Do you fancy one?’

‘Don’t treat me like I’m soft in the head,’ says Sid. ‘You were trying to get that bird to go out with you, weren’t you?’

‘I was just being pleasant,’ I say. It never pays to tell too much to Sid. Although he is married to my vivacious sister, Rosie, he is not above thrusting his pelvic area and appurtenances into close contact with any lady’s mole-catcher. He has seen more crumpet than your friendly local baker — in fact it was Sid who gave the trade the idea of putting holes in the middle of doughnuts — and he does not mind playing with his friends’ toys.

‘Going to take her home, are you?’

‘I was thinking about it,’ I say. ‘But there are nine of them in the flat. You know what it’s like? Her mum’s just come back from Nightingale Lane with another one.’

‘You find a lot of them down there,’ says Sid. ‘Ah well, sup up. No sense in being downcast about it. Women aren’t everything, are they?’

‘You’re right, Sid,’ I say, trying to sound as if I am putting a brave face on it. ‘There’s comradeship, isn’t there?’

‘A few pints of ale between friends. What could be better. Drink up, Tim lad. You don’t fancy a short, do you?’

I have never known Sid so full of the milk of human kindness. It is practically curdling in the face of the unexpected warmth. As I stand in the gents’ wondering why anyone should want to write ‘I had my sister in a pair of Wellington boots’ on the pebble dash wall — I mean, it is so difficult apart from anything else — I also chew over whether Sid is preparing himself for the key role he intends to play in the bedding business — I must say it does seem the right business for Sid.

I later learn that my naive faith in Sid’s good nature was misplaced. I have just helped Pearl — yes, that’s her name — remove something rather unpleasant from her shoe — those platform jobs don’t half spread it around — and the lights at the edge of the common are in sight when she starts moaning. ‘I’d have taken your friend’s offer if I’d known,’ she says. ‘Do you want your handkerchief back?’

‘You must be joking,’ I say. ‘What offer?’

‘He said he’d take me up west for a meal.’ Sid only meant West Clapham but it is still a better offer than I came up with. The crafty sod! No wonder he was keen to get up to the bar.

You can’t trust anyone can you?

‘He’s got a Rover 2000, hasn’t he?’

I decide to ignore this remark. ‘Lovely night, isn’t it?’ I say. ‘I do like a stroll.’

I don’t mind a stroll. It’s hiking I object to. You told me it was just round the corner.’

‘Once we get off the common it’s just round the corner.’ She is not exactly overdoing the pre-foreplay, this one. I hope I am not dooming myself to disappointment. It is distressing how white hot favourites can sometimes turn colder than last year’s Christmas pudding. There is no accounting for women.

‘Cut across here,’ I say. ‘Sorry mate.’ I am addressing the uppermost of the two people I have just tripped over. It is so dark once you get off the path. The bloke makes a strange grunting noise but I don’t think he is talking to me.

‘Disgusting!’ says Pearl. ‘Why did you have to bring me this way?’

‘It’s a short cut,’ I say, trying to steer her away from the bloke who is throwing up in the waste paper basket. ‘If we go — no.’ I don’t think that couple against the tree are studying lichen. Knickers! It is not exactly the best introduction to a night of wild passionate ecstasy. Most of these people seem to know each other rather better than we do.

By the time we get to 17 Scraggs Lane I am humming to keep my spirits up.

‘Is this it?’ says Pearl. She sounds as excited as some bird being fixed up with Frankenstein’s monster on a blind date. I know they don’t live in rude mud huts in Trinidad — polite mud huts at the worst of times — but I was not expecting to be taken to task for the family home.

‘These houses are very sought after in Putney,’ I say, quoting something that Mum is always saying.

‘It must have heard,’ says Pearl. ‘It’s leaning towards Putney.’

‘Very funny,’ I say, opening the front door and sticking my tongue out at Mrs Tanner, our new neighbour. She is always peering through her lace curtains and it drives me round the twist. Once I took Dad’s moose head round and tapped it against her front window and she had a police car on the door step in two and a half minutes flat. I had only just closed the back door behind me when I heard it screaming down the street. I wish I could have caught an earful of what she told them. They didn’t hang about for long. ‘Now, tell me, madam. Was there anything particularly distinctive about this moose? Anything you would remember if you saw him again?’

‘No officer. I’m afraid he was just like any other common or garden moose.’

‘It makes it very difficult for us, madam. Are you absolutely certain he had no distinctive features? Listen. I’m going to read you a list of things he might have been wearing in order to jog your memory: surgical truss, bowler hat, long pants — over the trousers. MCC blazer.’

‘Why are all these gas masks hanging in the hall?’ says Pearl. She sounds slightly frightened and very unimpressed.

‘My father collects things like that,’ I say. ‘He’s fascinated by anything to do with war.’

Pearl shudders. ‘Sounds unhealthy to me. What about the wooden legs?’

‘They came from North Staffordshire. We use them as firewood.’ That doesn’t sound very nice, does it? I wish Dad would nick a more superior class of article from the lost property office. It is difficult to explain the situation to visitors. They would never believe some of the things people leave on trains. Dad is like one of those Scavenger Beetles that goes around disposing of lumps of shit. He gets rid of the stuff that nobody claims. Society owes him a debt really.

‘Does the barometer wo —’

‘Don’t —’ Too late. The glass has fallen off again. People will keep tapping it. ‘It’s waiting to be mended. You didn’t see which way the hand went did you?’

It is difficult to see anything in the hall because after the cost of electricity went up again our wattage came down to a level which would cause complaints at a teenagers’ snogging party. You can hardly see your hand in front of somebody else’s tit. It does create rather a gloomy atmosphere and I can see that Pearl is having no difficulty in resisting the temptation to shout ‘Fiesta!’ and run round the front room with one of the plastic roses between her teeth.