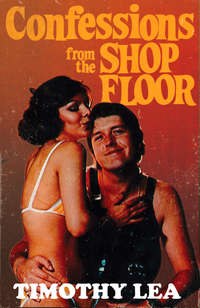

Confessions from the Shop Floor

‘Come into the drawing room,’ I say. I call it the drawing room because of some of the things my nephew Jason Noggett drew on the wall with his felt pencil — I don’t know where a child that age hears the words, really I don’t. Unfortunately they didn’t come off without smudging and this meant that the settee had to be moved against the wall to hide them. This liberated a large stain in the middle of the carpet and a pink latex brassiere which nobody claimed, neither of them. Sid said that Dad must have brought the bra home from the L.P.O. which didn’t go down very well. In order to cover the stain. Mum moved the fireside rug but this revealed all the scorch marks and holes where I had tried to pick out the pattern of the carpet with a red hot poker — of course, I was just a child at the time and I didn’t really know what I was doing — until the fire brigade arrived, that is. In the end, Dad solved the problem by bringing back a screen which we were able to put against the wall where Jason had done his stuff — I mean, the writing. At first, I thought the screen came from the L.P.O. but when I read that a bloke had fallen down a manhole on to some geezers who were repairing a power cable, I had another think. The initials L.E.B. were a bit of a give away, too.

‘There we are,’ I say proudly. ‘Do you want to watch telly while I get us a cup of tea?’

‘Have you got a colour set?’ she asks.

‘Oh yes,’ I say. ‘What colour would you like?’

‘What do you mean?’ She sounds startled. Maybe I should have explained. It isn’t exactly a colour set. It’s a black and white set and Dad got hold of these strips of tinted perspex. You prop them in front of the screen to get a colour effect. It is not very realistic and the perspex is so thick it is difficult to see the picture. Still, it is quite ingenious, isn’t it? Unfortunately, Pearl does not seem to agree with me when I explain it to her and starts poking around the room — not a bad idea when you come to think of it. ‘What are the dentures doing at the bottom of the fish tank?’ she says.

The correct answer must be ‘growing a kind of green mould’, but I do not give it. ‘They must be Dad’s,’ I say. ‘Jason — he’s my little nephew — was messing about with them. Dad will be pleased.’ At least, he will be pleased that they have been found. It is not surprising that nobody has noticed them up to now. The tank is pretty dirty and the dentures look not unlike an ornament as they sit grinning amongst the coloured gravel.

‘Don’t get them out now,’ says Pearl with a shudder as I start rolling up my sleeve.

‘All right,’ I say. I can see what she means. The sight of Dad’s best gnashers covered in green slime doesn’t exactly make you come out in a romantic flush. ‘Tea or coffee?’

‘What kind of coffee is it?’

‘Nescafe.’

‘Do you have any real coffee?’

‘It is real coffee. Out of a jar.’ I suppose coming from Trinidad she doesn’t know about things like that.

‘I’ll have tea, thank you.’

I don’t argue with her but flash into the kitchen. It is now getting on for midnight and I don’t have a lot of time to waste. Dad should soon be taking Mum in his arms for the last mazurka. I clean the dribbles off the teapot spout with a rag I find in the sink and start bunging things on a tray. Some uncouth bugger has helped himself to the sugar with a wet teaspoon so there are unattractive brown lumps and streaks all through the basin. I get cracking with rag and fingers and try and clean things up. In the end I find it easier to bury everything under a fresh avalanche of sugar. The kettle is taking a long time to boil which I find is because I have switched on the wrong ring. Dear oh dear. I hope it isn’t going to be one of those nights. I try and put a gloss on everything by digging out some cakes I find at the back of the cupboard but it occurs to me that the little chocolate flakes may be mouse droppings so I abandon the idea. The yellow icing was going a nasty transparent colour anyway, as I find out when I try and scrape away the mould. Blimey, this bird had better turn up trumps after all the effort I am putting in. In the end, I settle for some soggy biscuits and lug the whole lot back on a tray.

‘I’m afraid we’re out of milk,’ I say.

She looks at me in a funny sort of way. ‘You needn’t have bothered,’ she says. ‘I can’t drink it without milk. Is this what you brought me all the way here for, a cup of black tea?’

I put the tray on top of the telly and sit down beside her on the settee. A straight question deserves a straight answer. ‘No,’ I say. I gaze into her minces and suck in my breath sharply as if her wild animal beauty defies description.

‘What is it?’ she says. ‘Has one of my lashes smudged?’

‘They’re perfect,’ I say. ‘Like — like —’ once again she can feel me struggling for words ‘— like you. You’re just too much.’

‘Do you feel all right?’ she says.

‘I know it sounds ridiculous me talking like this,’ I say. ‘But I can’t help it. It’s the effect you have on me. You draw the words out of me — words I never thought I could utter. It’s some strange kind of magic.’

‘Do you have a proper drink?’ she says. ‘Something alcoholic. The way you go on I should think you must have.’

I cannot help feeling that I am not getting through to her. The old verbal magnetism is dropping a bit short of target.

‘I’ll have a look,’ I say. ‘I know we were running low.’ Understatement of the year. Last Christmas we must have been the only family in the land toasting the Queen in Stone’s Ginger Wine. Ever since I was a kiddy I have looked at a bottle of scotch like it was inside a glass case. I open the lower door of the sideboard and glance inside. There are a number of cork table mats which have been attacked by mice, a paper streamer and a pile of yellowing Christmas cards going back to the early fifties. Mum says she keeps the cards because she likes the pictures but it is really because it is the only way we can get a mantlepiecefull. When we get a Christmas card it is like another family getting a present. Everybody gathers round and it is passed from hand to hand and turned over to see how much it cost and if it came from the 2p section at Woolworths. The best card we had last year was addressed to somebody else and came to us by mistake. First of all we opened it to look at it and then we kept it. It showed a lot of geezers in top hats blowing trumpets from the back of a coach drawn by six black horses which are approaching an inn called ‘Ye Swanne’ practically buried in a snow drift. Inside, it said ‘May all your Christmases be white, and future prospects mighty bright. Thinking of you this happy Yuletide, Harry, Doris and family — not forgetting Cuddles’. We thought about them a lot, especially Cuddles. I wonder what he was — or she, maybe. It was funny how the infrequent visitors to the house all picked up the card and nodded like they had known Harry and Doris all their lives. I hope we get something from them next year.

‘Oh dear,’ I say. ‘That’s amazing. You have to come at the one time when we’re out of everything. Isn’t there something else I can get you? We’ve got some cocoa.’

‘I like cocoa without milk even less than tea without milk,’ says my dusky dreamboat sulkily.

‘Anything good on the telly?’ I say. ‘I see you’ve got it going.’

‘Just an old movie,’ she says. ‘I don’t know where they dig them up from.’

‘It’s probably black and white anyway,’ I say, trying to cheer her up.

‘Ronald Coleman,’ she says. ‘I can’t see what anyone ever saw in him. That moustache.’

‘The bird’s all right,’ I say, sliding on to the settee again. ‘Her clothes look quite modern, don’t they?’ I advance my hand along the back of the settee and let my fingers brush against her shoulders. Neither of us is getting any younger and my brooding, passionate nature demands an outlet.

‘Uum.’ She doesn’t tell me to piss off so I move my sensuous lips to her shell-like lobes and blow gently. She flicks her head like a disturbed cat. ‘Don’t do that.’

‘How long have you been over here?’ I ask.

‘Eighteen years.’

‘Eighteen years!’ The scent of bougainvillea blossom is obviously long dead in this bird’s nostrils.

‘I came over when I was a baby.’ She stifles a yawn. ‘Have you got a record player or anything?’

‘It’s at the menders,’ I say. In fact we do have a gramophone but it looks like the picture on an old HMV sleeve and was ‘rescued’ by Dad. I can’t see Pearl’s sophisticated tastes responding to it. Especially the selection of old Maurice Chevalier records that came with it. ‘Lets make love,’ I say. I suppose I could have built up to it a bit more but there is not a lot of time to waste and I need to know where I stand. It is also a fact that birds can sometimes respond well to the frank, straightforward approach. After all, they all know what it’s about and they must get bored waiting for you to wring out the words.

‘You don’t waste a lot of time, do you?’ she says.

‘When you feel the way I do, there’s not a lot of point.’ I say. It doesn’t mean anything but I put a lot of sincerity into it.

‘Nobody could accuse you of trying to buy me, could they?’ she says.

‘I couldn’t do it,’ I say. ‘I’m no saint but I do have a few scruples.’

This is another effective ploy. Just as birds are always prepared to believe you when you say something nice about them, they are also prepared to give you the benefit of the doubt when you say something nasty about number one. This way, you come out as being honest, in need of help, and slightly exciting. You can appeal to a number of their cravings with one simple approach. Frank Sinatra was a master of this gambit as a study of some of his old movies on the telly will reveal: ‘If you know what’s good for you, you’ll stay away from me, kid. I’m poison to dames. I just foul them up, see? Stick with me and you’ll earn yourself a groin-full of groans.’ Of course, once he’d said that, knocked back a couple of fingers of Jack Daniels and flipped his snap-brimmed hat on to the back of his head they had to plane the birds off him in layers.

‘It’s not very romantic down here.’

Note the use of words carefully. She does not say ‘in’ here but ‘down’ here. This clearly indicates that the possibility of being ‘up’ somewhere has clearly entered her mind — as indeed it has entered mine. In her case I think she is thinking about ‘upstairs’.

‘Let me show you round,’ I say, very casual. ‘There’ll be a collection for the National Trust at the end of the tour. Please give generously.’ I run my fingers up her body as I get to the last bit and turn the telly off with a flourish. When she has helped me pick up the tea things we go out into the hall. I wish I was not so clumsy. Still, maybe she will put it down to my impetuosity.

‘Where’s the bathroom?’ she says.

‘Top of the stairs. Follow your nose.’ She looks at me a bit old fashioned. ‘I mean straight on.’ I suppose I could have chosen my words better.

I take the tray into the kitchen and then I think of something. ‘Watch out for the —’ There is a shrill scream from the bathroom — ‘gorilla in the bathroom,’ I finish lamely.

Dad keeps his gorilla skin in the bathroom because of the steam and it can give you a nasty turn if you’re not expecting it — which, let’s face it, very few people are.

‘Oh my God!’ says Pearl when I get to her side. ‘I saw it in the mirror. I thought it was coming to get me.’ The skin is hanging on the door and I can see what she means. Grab a gander at your mug and there it is leering over your shoulder.

‘It’s all right. I’m here,’ I say, taking her in my arms and pressing my cakehole against her barnet. Well done, Dad’s gorilla! This is just the little ice-breaker I needed. As I have said on many occasions it is vital to establish unforced bodily contact at the first opportunity.

‘It’s horrible!’ she shudders. I think she is referring to the gorilla but it may be the pressure of my giggle stick against her dilly pot that is causing anxiety. Percy is coming on strong as they say. Nothing feeds his base appetites more than the sight of a damsel in distress.

‘Let’s get out of here,’ I say. I don’t wait for her to consult her horoscope but lead her towards my room. A glance through the door makes me change my mind. I had forgotten that I had been stripping down the gear change on my bike. There are bits and pieces all over the bed. I don’t want to sweep her on to it impulsively and find that I have wedged an axle nut up her khyber.

‘In here.’ I don’t like using Mum and Dad’s bedroom but passion makes you reckless, doesn’t it? My high-thigh equipment is itching for action and in situations like this it is inclined to programme my thought box.

‘It’s all right in here, is it?’ I see Pearl’s eyes nervously scanning the walls for signs of gorillas or worse.

‘You bet.’ I take her cheeks between my hands and home on to her mouth like a bird settling on its nest. My tongue starts painting a mural on the roof of her mouth and I rub my chest backwards and forwards across her bristols. She is wearing one of those stretch silk blouses with puff sleeves and I flick my digits across the strawberries that show through. ‘You’ve got a mole down there, haven’t you?’ I murmer. I am talking about her cleavage but she looks down at the floor as if imagining that the gorilla might have a friend. ‘Here,’ I say, sticking a finger down the front of her blouse.

‘Yes. I never had it when I was a kid.’ I don’t make any comment but push her back on to the bed and start moulding the front of her jeans. I do wish birds would give up wearing trousers. I feel unhealthy touching up somebody turned out like a bloke. Mum’s bed has an eiderdown on it and Pearl sinks into it so deep that you wouldn’t be able to see her from the other side of the room. Not that I am going to look, mind you. I like it too much where I am.

I unpop the front of her jeans and then carry on popping up to the top of her blouse. She must have shapely knockers because they don’t disappear when she is lying on her back. You know what some birds are like when in the Egyptian PT position — only their nipples mark the spots. I start fiddling for the catch on her bra but she shakes her head.

‘It doesn’t have one.’ Funny how birds clobber changes, isn’t it? I can remember when bra cups were like plastic beakers. Now they are as flimsy as Ted Heath’s re-election prospects. I expose a couple of gnawable nipples and set to with a will — and a willy as I am reminded by the eager force battering the front of my brushed denim. You might well think that the back of my zip was a xylophone and that my love portion was practising its scales. My lips spill a confetti of kisses down to Pearl’s tummy button and from this position I direct the assault on her jeans. Not that it is much of an assault. Pearl obligingly raises her shapely haunches and together we push the encumbering threads down to ankle level. She is wearing a pair of flowery panties and the white background sets off her light brown skin a treat.

‘What about you?’ Yes, what about me, indeed. With Pearl’s unneeded help I rip open my shirt and wriggle out of my jeans like there is a prize for doing it fast. Percy bounds forward eagerly and only the frail fragment of my navy blue, silk-effect athlete’s briefs keeps him in half-hearted check. Gently at first, as if tip-toeing across a minefield, Pearl brushes her fingers over my truncheon meat. ‘He’s keen, isn’t he?’ she says.

‘Keen?’ I say. ‘He’s a raving maniac!’

As I say this, her fingers take a steely grip on my hampton and she kisses me like she is trying to organise a tongue transplant. She may have been eighteen years out of the country but a lot of the old jungle magic still remains.

‘Put him to work.’ She arches her back and shows me her teeth — by opening her mouth, I hasten to add. She doesn’t fish them out of her back pocket.

I am not the man to deny a lady such a request and I swiftly scramble to my knees and tug down her nicks. Her own fingers are not idle. She flicks down the rim of my pants so that Percy peeps over the top like we are having a Punch and Judy show.

‘Peek a-boo!’ she says.

Percy does not say anything. With him, actions speak louder than words as I hope to show the Caribbean curve carnival. Keeping my fingers in reggae rhythm, I check that all parts are in good working order and enthusiastic about the imminent arrival of Mad Mick. As she looks up at me expectantly I discard my pants and position myself on the starting grid.

‘Go on.’ That counts as the chequered flag as far as I am concerned. With a screech of balls I roar up the straight and head for the first bend. The Grand Prick of Clapham is under way. I could give you all the sordid details but I know that you are a sensitive bunch and would probably skip to the end of the chapter. Suffice to say that this chick performs like a mechanical sludge sifter gone berserk. I have never known such a mover. The bedhead bashes against the wall and the light in the middle of the room starts swinging. What a pity that one of us has to catch a toe in the eiderdown. That’s right. Suddenly, the room is full of feathers. You have never seen anything like it. Talk about plucking a chicken. I feel more as if I am — what was that? I stop moving and my blood freezes. It sounded like the front door.

‘I’d never have bleeding gone if I’d known he wasn’t going to give us a lift back.’

‘Oh, stop your moaning!’

Mum and Dad are back! Eek! Immediately, panic replaces passion, and my nunga wilts like a blob of fat at the bottom of a hot frying pan. My feet hit the floor and I start pulling on my jeans. Bugger! They are not my jeans. Bleeding unisex! Bleeding sex!!

‘Get your clothes on!’ I hiss. ‘They’re coming!’

‘I should be so lucky,’ says the bird sulkily.

‘I don’t care about you. I’m going to bed.’ That is Mum coming up the stairs. Oh my gawd! Why did I ever get myself in this situation? I must stop her coming in to the bedroom.

I brush some of the feathers off my shirt and hobble to the door trying to wriggle my feet into my slip-ons. I fling the door open just as Mum’s hand is stretching out for the knob.

‘Timmy! What on —’ I close the door behind me and stand in front of it.

‘Did you have a nice time?’ I say. A feather that has become attached to my lips soars into the air as I speak.

Mum stares at it suspiciously for a second before ignoring my considerate question. ‘What were you doing in there?’ she says. ‘Why are you covered in feathers?’

She tries to go into the room but I continue to bar the way. Dad appears at the top of the stairs. He takes one look at me and stops dead. ‘Blimey!’

They both stare at me and panic lights flash before my eyes. What can I say?

‘Have you got someone in there?’ says Mum. Dad grits his teeth and takes a menacing step towards me.

‘You mustn’t go in!’ I squeak.

‘And why not, pray?’ snarls Dad.

‘She’s getting herself ready to meet you,’ I gulp.

‘Who is?’ Mum’s voice rises sharply and she steps forward beside Dad.

‘My fiancée,’ I say.

‘What!!?’ They say the word together and take a step backwards like I have produced a gun. It is a masterstroke. Now they look bewildered. Seconds before they looked like a lynching party.

‘Hi dere!’ Pearl comes out of the bedroom smoothing the ruckles out of the front of her blouse at skirt level.

Dad catches Mum just before she hits the floor.

CHAPTER TWO

One of the strangest things about my “engagement” to Pearl is that Mum never mentions it — apart from saying that she will drop dead if we ever walk up the aisle together. She doesn’t even say anything about the eiderdown. As a gambit — which is what I believe they call them in some circles — it is well worth remembering. The next time your mum or dad catch you on the job with someone, say that you’re going to marry them. They’ll be so horrified they won’t bother to castigate you — it’s OK, it doesn’t mean what it sounds like. Sometimes I think that parents experience the reverse of what I feel when I imagine them on the job. It turns them right off to think of their little boy or girl indulging in all those nasty goings-on.

Of course, the fact that Pearl has joined the brownies without having to buy a uniform slips down less than a treat but it isn’t the whole story. Sid hears about it from Rosie when she drops in to see Mum and he is full of interest as we drive to see Slumbernog — that is the daft name he has come up with for the company we haven’t even seen yet. He was going to call it Slumnog until I spelt it out to him.

‘You jammy old bastard,’ he says. ‘What was it like then? I hear they’re a bit special.’

‘Sidney, please!’ I reproach him. ‘Do you think I’m the kind who scatters the secrets of the nuptial couch?’

‘But you aren’t going to nupt her, are you?’ asks Sid. ‘I believe the ceremony is very embarrassing. You have to give her one while you’re signing the register.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ I say.

‘All your relations standing about watching you,’ muses Sid. ‘I wouldn’t fancy it.’

‘Well, don’t disturb yourself,’ I tell him. ‘It’s not going to happen.’

In fact, nobody need get their knickers in a twist because I haven’t seen Pearl since the night in question. I think she was a bit upset by some of the remarks Dad made. When he saw all the feathers in the bedroom he thought we had killed a chicken.

‘Coming round here with your voodoo love rites!’ he kept shouting. ‘We don’t want no jungle loving in this house!’ It was all very embarrassing.

‘How much further have we got to go?’ I say, deciding that the time has come to steer the conversation into less controversial waters.

‘Just along here by the river. Nice, isn’t it?’

I don’t answer immediately because I am not certain whether he is joking. It depends whether you call boarded up buildings and collapsing warehouses nice.

‘It seems to be coming down faster than a snail’s knickers,’ I say warily.

‘That’s good isn’t it?’ says my idiot brother in law cheerfully. ‘Rents will be low and we’ll be able to keep the overheads down.’ He starts whistling “Old Father Thames” and rubbing his hands together.

‘I should think the overheads will all be at floor level anyway,’ I say. Sid slams on the brakes and pulls into the kerb.

‘Are you feeling all right?’ I say.

Sid turns off the engine and bashes his nut on the windscreen because he hasn’t taken it out of gear first. He curses softly and faces me. ‘You’ve got to change your attitude. All this fas-fash-vas —’

‘Vasectomy?’ I prompt.

‘Facetiousness has got to stop. If you’re going out on the shop floor you’ve got to do so in the right attitude. Serious, alert, responsible —’

Hang on a minute,’ I say. ‘Shop floor? I thought you were taking over this place?’

‘And you thought you were going to end up with some cushy number sitting behind a big desk?’ Sid shakes his head. ‘Oh no, Timmo. It’s not going to be like that. That’s the besetting sun of British industry, that is. Management up there, workers down there. With me at the helm, it’s going to be different.’

‘You mean it’s going to be Sid up there, Timothy down there?’

Sid bashes his mitt on the dashboard. ‘There you go again. You can’t be serious, can you? What I’m saying is that we’ve got to integrate ourselves with the labour force. We’re all working to the same end. We’ve got to understand their problems, feel their grievances. And you can only do that by working alongside them.’

It has not escaped my attention that the “we” has changed to “you” at a very crucial moment. ‘Are you going to work on the shop floor, too, Sid?’

‘Up here,’ says Sid. ‘Up here.’ A fanciable bird is passing the car and for a moment I think he is saying “Up her!” Then I see that he is tapping his nut. ‘In my mind I will always be shoulder to shoulder with the workers. Their struggle will be my struggle, their sweat will be my sweat —’