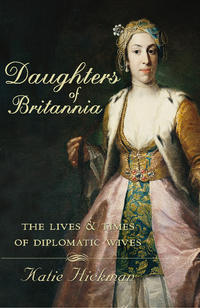

Daughters of Britannia: The Lives and Times of Diplomatic Wives

Useful items of personal apparel include ‘several full-sized silk gossamer veils to wear with your topee’ and ‘a most liberal supply of tulle, net, lace, ruffles, frillings, white and coloured collars and cuffs, artificial flowers and ribbons’. Furthermore ‘pretty little wool wraps to throw over the head, and an opera cloak, are requisites which should not be overlooked’. Among essential household items the major lists mosquito curtains, punkahs, umbrellas and goggles; when travelling by sea, a lounge chair; drawing materials, wool and silks for ‘fancy work’; a water filter, lamps, a knife-cleaning machine; and no fewer than half a dozen pairs of lace curtains. Other recommended sundries include:

a refrigerator

a mincing machine

a coffee mill

a few squares of linoleum

cement for mending china and glass

Keatings insect powder

one or two pretty washstand wall-protectors

a comb and brush tray

bats, net and balls for lawn tennis

one or two table games

a small chest of tools including a glue pot

a small box of garden seeds

a small garden syringe

chess and backgammon

a few packs of playing cards

a Tiffin basket

Tropical Trials was, thankfully, by no means the only handbook of its kind to which a woman planning a life abroad could turn. Flora Annie Steel’s celebrated book The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook, first printed in 1888, was so popular in its day that it ran to ten editions. Although it was dedicated ‘To the English girls to whom fate may assign the task of being house-mothers in Our Eastern Empire’, its sound good sense and truly prodigious range of recondite advice – from how to deal with snake bite (‘if the snake is known to be deadly, amputate the finger or toe at the next joint …’) to how to cure ‘bumble foot’ in chickens – made it just as useful to diplomatic women living outside the empire.

Unlike the major, Annie Steel had no time at all for fripperies.* ‘As to clothing, a woman who wishes to live up to the climate must dress down to it,’ was her sensible advice. Frills, furbelows, ribbons and laces were quite unnecessary, she believed. None the less, the clothing which even she considered essential would have taken up an enormous amount of trunk space. ‘Never, even in the wilds, exist without one civilized evening and morning dress,’ she urged, and listed:

6 warm nightgowns

6 nightgowns (silk or thin wool) for hot weather

2 winter morning dresses

2 winter afternoon dresses

2 winter tennis dresses

evening dresses

6 summer tea gowns*

4 summer tennis gowns

2 summer afternoon gowns

1 riding habit, with light jacket

1 Ulster†

1 Handsome wrap

1 umbrella

2 sunshades

1 evening wrap

1 Mackintosh

2 prs walking shoes

2 prs walking boots

2 prs tennis shoes

evening shoes

4 prs of house shoes

2 prs strong house shoes11

On the actual journey, however, circumstances were often rather more frugal than these preparations suggest. When Diana Shipton travelled to Kashgar it was so cold in the mountains that she and her husband put on every garment they possessed and did not take them off again for three weeks. On one of her journeys in Brazil Isabel Burton once went for three months without changing her clothes at all. Sometimes, though, such spartan conditions were imposed more by accident than by design. When Angela Caccia, her husband David and their newborn son were posted to Bolivia in 1963 they made the journey by sea, taking with them an enormous supply of consumer goods, from tomato ketchup to soap powder. This luggage came with them as far as Barcelona, where it was lost, leaving them to face the six-week ocean voyage with little more than the clothes they were wearing. For the baby they did have clothes, but no food; ‘David had 75 ties; I had 9 hats, and between us we had 240 stiff white paper envelopes.’

However, the journey itself was so entrancing that the Caccias soon forgot these inconveniences. Their route took them through the Panama Canal and then down the Pacific coast of South America to the Chilean port of Antofagasta, from where they took a train across the Atacama and up into the Andes. Angela was spellbound by the beauty of the desert, despite the fact that the air was so thin and dry that their lips cracked and their hands hissed if they rubbed them together as if they would ignite. The light was so intense, she recorded, that they wore dark glasses even inside their carriage with the curtains drawn.12

Very few diplomatic women were as experienced, or as naturally adept at travelling as Ella Sykes – or certainly not at first. The journey to a posting was often a woman’s first taste of travelling abroad, and it left an indelible impression on her – although not always the same sense of wonderment experienced by Angela Caccia. Reading back over my mother’s very first letters, written during the six-week sea voyage out to New Zealand in 1959, I find, to my surprise (for I have always known her as the most practised of travellers), a note of apprehension in her tone.

I suppose quite shortly we shall really be at sea [she writes from her cabin aboard the S.S. Athenic]. Atlantic rollers may begin, instead of the millpond the Channel has been up to now. We have been sailing in dense fog all day. It is a queer sensation to have thick mist swirling around with visibility about the length of the boat, the foghorn sounding every few minutes and bright sun shining down from above. We seem to be travelling at a snail’s pace.

It is also a surprise to be reminded that even then such a voyage was still considered a special undertaking. My parents arrived at the London docks to find themselves inundated with well-wishers.

We were taken straight to our cabin and found a large box of flowers from Auntie Olive, also from Betty and Riki, and telegrams from Hilary and Tony, J’s mother, Auntie Jo and Jack, Sylvia Gardener, and Richard Hickman. After the ship sailed at eight o’clock last night I found Mummy’s wonderful boxes of Harrod’s fudge and chocolates, and Hilary’s [my mother’s sister] stockings. Thank you so much both of you. It was all the nicer getting them then, after we had left the dock and were feeling a bit deflated. Thank you Mummy and Daddy also for the beautiful earrings, which J produced after dinner … I wonder if you realised how much I wanted something just like them?

There was no such send off for Isabel Burton when she took to the seas on her first posting in 1865. In her hotel room in Lisbon, where she stayed en route to Brazil, she was greeted by three-inch cockroaches. Although she could not know it then, it was only a taste of what was to come. ‘I suppose you think you look very pretty standing on that chair and howling at those innocent creatures,’ was Richard’s characteristically caustic response. Isabel reflected for a while, realized that he was right, and started bashing them instead with her shoe. In two hours, she recorded, she had a bag of ninety-seven.

For some women, the journey was the only enjoyable part of diplomatic life. The writer Vita Sackville-West loathed almost every aspect of it (the word ‘hostess’, she used to say, made her shiver), but her first impressions of Persia, recorded when she travelled there to join her husband, Harold Nicolson, in 1926, echoes the experience of many of these peripatetic wives. On crossing the border she wrote:

I discovered then that not one of the various intelligent people I had spoken with in England had been able to tell me anything about Persia at all, the truth being, I suppose, that different persons observe different things, and attribute to them a different degree of importance. Such a diversity of information I should not have resented; but here I was obliged to recognise that they had told me simply nothing. No one, for instance, had mentioned the beauty of the country, though they had dwelt at length, and with much exaggeration, on the discomforts of the way.

The land once roamed by the armies of Alexander and Darius had, to Vita’s romantic imagination, a kind of historical glamour that its contemporary inhabitants never quite equalled. It was ‘a savage, desolating country’, but one that filled her with extraordinary elation. ‘I had never seen anything that pleased me so well as these Persian uplands, with their enormous views, clear light, and rocky grandeur. This was, in detail, in actuality, the region labelled “Persia” on the maps.’ With the warm body of her dog pressed against her, and the pungent smell of sheepskin in her nostrils, Vita sat beside her chauffeur in the front seat of the motor car with her eyes fixed in rapt attention on the unfolding horizon. ‘This question of horizon,’ she wrote musingly later, ‘how important it is; how it alters the shape of the mind; how it expresses, essentially, one’s ultimate sense of a country! That is what can never be told in words: the exact size, proportion, contour; the new standard to which the mind must adjust itself.’13

On that journey, she believed, Persia had in some way entered her very soul. ‘Now I shall not tell you about Persia, and nothing of its space, colour and beauty, which you must take for granted – ’ she wrote to Virginia Woolf on her arrival in Tehran in March 1926, ‘but please do take it for granted, because it has become part of me, – grafted on to me, leaving me permanently enriched.’ But the exact quality of this enrichment even she found hard to put her finger on. ‘But all this, as you say, gives no idea at all. How is it that one can never communicate? Only imaginary things can be communicated, like ideas, or the world of a novel; but not real experience … I should like to see you faced with the task of communicating Persia.’14

Such difficulties, however, were as nothing compared to the difficulties and hardships often involved in the actual travelling itself. When Mary Fraser set off from Venice to make the journey to Peking in 1874 she was unprepared for the rigours of her first diplomatic journey, even though, having lived in Italy and America, she was relatively well travelled for a young woman. At first all was well, even though she could not help noticing the strange smell on board their boat: ‘the abominable, acrid, all-pervading smell of the opium cargo it was carrying’. By the time they reached Hong Kong, however, they had other worries: the worst typhoon in fifty years had all but destroyed the little island.

The P & O agent who came to meet their boat, ‘ashy pale and still trembling in every limb’, described how the storm had literally ripped apart the island in less than two hours. All shipping vessels had been wrecked, half the buildings ruined and not a single tree had been left standing in the Botanical Gardens. Worse than all this, though, was the fate of Hong Kong’s coolies and their families who had been living in sampans in the harbour – an estimated 10,000 had been drowned. By the time the Frasers arrived the water in the harbour was awash with the floating bodies of men, women and children. As she disembarked, Mary accidentally stepped on one of them and thereafter, ‘I could not be left alone for a moment without feeling faint and sick.’ In the tropical heat the corpses were already beginning to putrefy. Pestilence was all around and the atmosphere, she recalled with horror, ‘was that of a vast charnel house’.

The Frasers then travelled on to Shanghai without incident, and Mary recovered her composure enough to enjoy the rest of the journey, even the final stretch up the Pei-Ho river, although at first she surveyed the preparations with dismay. For the five-day river journey they had a fleet of five boats, each with five boatmen. Three of these carried their luggage; one was a kitchen and store room; while the fifth was fitted up snugly as a sleeping room and dining room. At night the boatmen pulled up the boards on the deck of their boat and, packed ‘like sardines in a tin’, they fitted the boards back tightly over themselves and slept peacefully. On the Frasers’ boat there was a little deck at the front with two chairs and ‘a tiny caboose sunk aft’, where a mattress could be laid on the floor at night. By day it was replaced by a table. ‘In the morning,’ Mary recalled, ‘poor Hugh used to hurry into his clothes, and go on shore for a walk, while I attempted to make my toilet, in all but darkness, with the help of one tin basin, muddy river water, and a hand glass.’

Although, unlike her husband, she was quite unused to these primitive travelling arrangements – ‘the Frasers’, she once commented, ‘are all Spartans’ – Mary was quick to learn a certain diplomatic stoicism. For most of the five days they spent on the Pei-Ho their servant, Chien-Tai, cooked ‘with marvellous success’ amidst her trousseau trunks in the kitchen boat and ‘not a course that we would have had on shore was omitted’; but on one terrible occasion, amidst torrential rain, the boats became separated and they had nothing to eat for a whole day. The two of them passed the day gloomily in the blacked-out caboose, lighted only by two meagre candles.15

On her journey to Constantinople in 1716 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, together with her husband and infant son, faced still greater hardships. On the mountain roads between Bohemia and Saxony she was so frightened by the sheer precipices that when she finally arrived in Dresden she could not compose herself to write at all. Their journey was all the more dangerous because they travelled at night, with only the moon to light their way.

In many places the road is so narrow that I could not discern an inch of space between the wheels and the precipice [she wrote to her sister Lady Mar]. Yet I was so good a wife not to wake Mr Wortley, who was fast asleep by my side, to make him share in my fears, since the danger was unavoidable, till I perceived, by the bright light of the moon, our postilions nodding on horseback while the horses were on a full gallop, and I thought it very convenient to call out to desire them to look where they were going.

As they travelled further south the danger of mountain precipices was replaced by another less dramatic but no less real peril: the weather. From Vienna Lady Mary wrote again to her sister on the eve of their journey through Hungary. It was January, and the entire country was so frozen by ‘excessive cold and deep snows’ that her courage almost failed her. ‘The ladies of my acquaintance have so much goodness for me, they cry whenever they see me since I have determined to undertake this journey; and, indeed, I am not very easy when I reflect on what I am going to suffer.’ Lady Mary’s usually sanguine tone begins to waver a little at this point; but when no less a person than Prince Eugene of Savoy, the Austrian general, advises her against the journey she begins to sound genuinely frightened.

Almost everybody I see frights me with some new difficulty. Prince Eugene has been so good as to say all the things he could to persuade me to stay till the Danube is thawed, that I may have the convenience of going by water, assuring me that the houses in Hungary are such as are no defence against the weather, and that I shall be obliged to travel three or four days between Buda and Essek without finding any house at all, through desert plains covered with snow, where the cold is so violent many have been killed by it. I own these terrors have made a very deep impression on my mind, because I believe he tells me things truly as they are, and nobody can be better informed of them.

She ends her letter, ‘Adieu, my dear sister. If I survive my journey, you shall hear from me again.’ And then, in an uncharacteristically maternal aside: ‘I can say with great truth, in the words of Moneses, I have long learnt to hold myself as nothing, but when I think of the fatigue my poor infant must suffer, I have all a mother’s fondness in my eyes, and all her tender passions in my heart.’

As it turned out, Lady Mary’s fears were not realized and the Wortley Montagus survived their journey. Although the snows were deep, they were favoured with unusually fine weather, and with their carriages fixed upon ‘traineaus’ (‘by far the most agreeable manner of travelling post’) they made swift progress. What they saw on the frozen Hungarian plains, however, shocked even their robust eighteenth-century sensibilities. Lady Mary recorded her impressions of the fields of Karlowitz, where Prince Eugene had won his last great victory over the Turks, in a letter to her friend, the poet Alexander Pope:

The marks of that glorious bloody day are yet recent, the field being strewed with the skulls and carcasses of unburied men, horses and camels. I could not look without horror on such numbers of mangled human bodies, and reflect on the injustice of war that makes murder not only necessary but meritorious. Nothing seems to me a plainer proof of the irrationality of mankind, whatever fine claims we pretend to reason, than the rage with which they contest for a small spot of ground, when such vast parts of fruitful earth lie quite uninhabited.16

But, as Lady Mary had found, the ‘tender passions’ provoked by the additional stress of travelling with small children were often difficult to bear. Catherine Macartney, yet another diplomatic wife to find herself posted to the wilds of Chinese Turkistan, describes the extraordinary precautions which she took to ensure the safety of her small son. Eric, her eldest child, was born in 1903 when the family was in Edinburgh on home leave, and was only five months old when they set off back to Kashgar. ‘It seemed a pretty risky thing to take so small a traveller on a journey like the one before us,’ Catherine wrote. Nonetheless, knowing what was ahead of them, she did all she could, almost from the day Eric was born, to prepare him for the journey. To harden him up she took him out in all weathers, and only ever gave him cold food (once they were in the Tien Shan Mountains she knew that it would be impossible to heat up bottles of milk). Eric apparently throve on it. Catherine described their travelling routine:

When we were in the mountains, his bottles for the day were prepared before starting the march, and carefully packed in a bag to be slung over a man’s back. As they needed no heating, he could be fed when the time came for his meals, and just wherever we happened to be. And the poor little chap had his meals in some funny places – cowsheds, in the shelter of a large rock, or anywhere where we could get out of the wind.

At night he slept in a large perambulator which they had carried along especially for the purpose. According to Catherine, ‘He stood the journey better than any of us.’

Five years later, in 1908, when the family went home on leave again, they were not so lucky. Eric was now five, his sister Sylvia two and a half. Flooding rivers had blocked the usual route through Osh, and instead the Macartneys decided to trek north over the Tien Shan, and then through the Russian province of Semiretchia, from whence they could reach the railway at Aris, just to the north of Tashkent. Catherine recorded it all in her diary. Despite her misgivings about travelling in the summer heats, she was overwhelmed by the beauty of the lakes and flower-filled meadows they passed through. The two children, who rode on pack ponies in front of two of the consulate servants, seemed to enjoy it too. It is not long, however, before a more anxious tone begins to colour her entries: ‘Thursday, July 23rd. We have beaten the record today and have done four stages, reaching Aulie-ata at about four o’clock this afternoon. Poor little Eric has been so ill all day with fever; but the travelling has not seemed to worry him much, for he has slept the most of the time in spite of the jolting. Our road has been across the grassy steppes and the dust was not so bad.’

The next day, to her relief, Eric was much better, and she was able to hope that it was just ‘a passing feverish attack’. Two days later it was clear that it was something much worse.

Sunday, July 26th. Today’s march has been done with the greatest difficulty, for the children have both been very unwell and can take no food whatever. They have not seemed themselves for some days, and today they have been downright ill. To make matters worse, I suddenly had an attack of fever come on, which decided us to stop at the end of our second stage at Beli-Voda. Eric and I had to go to bed, or rather to lie down on hard wooden sofas, and it was pitiable to see poor little Sylvia. She was so ill and miserable and yet wanted to run about the whole time, and seemed as though she could not rest. There was little peace for anyone, for we could only have the tiny inner room that was reserved for ladies, to ourselves. The whole afternoon travellers were arriving and having tea in the next room, talking and laughing and making a distracting noise. Happily we had the place to ourselves for the night. I am much better this evening, but the children seem to be getting steadily worse and we are becoming anxious about them.

The following day the two children were so ill that the Macartneys got up at dawn and made haste to the town of Chimkent, where they were told there was a doctor. The doctor advised them to stop travelling at once and, to Catherine’s relief, found rooms for them in an inn near his house.

It is delightfully cool and restful here, after the hot dusty roads [she wrote in a snatched moment] and a few days’ rest will, I hope, set us all up. The first thing we did was to give the children a warm bath, put them into clean clothes and get them to bed. They looked so utterly dirty and wretched when we arrived that I felt I must cry; and they were asleep as soon as they got between clean sheets … a sleep of exhaustion. Both of them have lost weight in the last few days.

It was the last entry she was to make for many weeks.

On 23 August Catherine finally resumed her journal.

Our two or three days here have lengthened into nearly a month, and a time of awful anxiety it has been. The children, instead of recovering in a few days, developed dysentery, and to add to our troubles Nurse took it too. For three weeks it was a fight for Eric’s life and several times we thought we would lose him. Sylvia, though bad enough, was not as desperately ill as Eric … My husband and I did all the nursing and during that time we neither of us had a single night’s rest, just snatching a few minutes sleep at odd times.

In spite of their rudimentary lodgings – two rooms so small that there was only space for the children’s and the nurse’s beds – they were comforted by the extraordinary kindness of the local people. The Russian doctor visited them sometimes as many as three or four times a day. And there were others, too, ‘who, simply hearing that we were strangers and in trouble, were most helpful in sending us goat’s milk, cake, fruit, and delicacies. It is when one is in such straits as we were that one discovers how many kind people there are in the world. But I never imagined that anyone could receive so much sympathy and practical help from perfect strangers as we did during that anxious month.’17

The Macartneys had been on the road for more than 800 miles before they finally arrived, exhausted, in Aris. From here they were able to pick up the Tashkent – Moscow train, and travelled onwards, first to Moscow, and then to Berlin via Warsaw. Although Eric suffered several relapses during that time, the family arrived safely in Edinburgh, three long and painful months after they had set out.

Like Mary Wortley Montagu with her traineaus, and Mary Fraser with her fleet of Chinese river boats, diplomatic women over the centuries have been obliged to take what transport they could find. Yet another Mary – Mary Waddington, who travelled to Russia to the Tsar’s coronation in 1883 – had several luxuriously appointed private railway carriages at her disposal, but a diplomatic wife was just as likely to find herself transporting her family by camel, yak, horse, palanquin, coolie’s chair, house-boat, cattle-truck, tukt,* sleigh or tarantass† as by more conventional methods.