Universe: The story of the Universe, from earliest times to our continuing discoveries

Contents

Cover

Title Page

1 A big Universe

2 In cosmic realms

3 Third rock

4 Our cosmic backyard

5 The galactic neighbourhood

6 Far and away

7 The Universe revealed

Glossary

Need to know more?

Further reading

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

1 A big Universe

Ever since our ancestors were first struck by the majesty of the heavens and pondered its meaning, human beings have felt a profound curiosity about realms beyond the Earth. Unimaginably distant and seemingly untouchable, the wider cosmos – from our closest planetary neighbours to the stars beyond – has inspired humans in countless ways through the centuries.

Splendour of the heavens

Although science has provided incredible insights into the Universe, our feelings of awe at viewing a star-spangled sky are the same as those experienced by our prehistoric ancestors.

Inklings of the infinite

Throughout history, everyone with the slightest degree of curiosity about the world around them has looked up at the sky and asked questions about it – seeking answers by questioning others, formulating their own theories and by arriving at their own answers through observation.

Galaxies in their thousands – a deep view of the Universe, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Eternal musings

How far away are the stars and what’s the furthest thing in the Universe that our eyes can see? Does it all go on forever? Are there other planets like the Earth, inhabited with beings intelligent enough to question who they are, and how they, their world and the Universe itself came into being? If the Universe is infinite, could there be another person like me wondering exactly the same things at that very same moment in time? Will they reach the same conclusions as me? These sorts of questions have been asked by people of all ages ever since our ancestors developed the mental capacity to lay aside their basic survival instincts for a moment or two and view the world around them – and the skies above them – with a genuine curiosity and a desire to know more about the cosmos.

Cosmic connection

The cosmos includes everything – the Earth included – and while science has amassed a great deal of knowledge about the physical nature of our home planet, the intricate processes at work on its living surface, and in its oceans and atmosphere, remain only partly understood. In modern times, living in a polluted big city where the Sun itself competes for attention amid the concrete canyons, it is easy for an individual to feel utterly detached from the Earth and the rest of the Universe – spiritually, mentally and physically. In the pre-industrial age, our ancestors were much more aware of the cycles of the heavens and the Earth. However, plant any 21st century urbanite beneath a dark, star-studded night sky, away from light pollution and the trappings of ‘civilisation’, and all those hardwired visceral feelings soon return.

Our physical bodies, our clothing and jewellery, the book you’re holding right now and the chair you’re sitting on – everything around you, including the planet beneath your feet – is all made from material produced inside long-dead stars. Knowing that we are made of ‘star-stuff’ allows us to feel more intimately connected with the Universe.

Viewing the awesome cosmos.

Sunshine and starlight

Without the stars, the night skies would lose much of their splendour; without the Sun, there would be nobody around to appreciate the stars. The Sun may not be the most important star in the cosmos, but it is critical to the existence of the Earth.

must know

Cosmic speed limit

Light travels at the staggering speed of around 300,000km per second. The Moon is 1.3 light seconds away and sunlight is around nine minutes old. Light from the nearest stars in our galaxy takes more than four years to reach us, and light from the most distant galaxies is billions of light years old. Nothing in the Universe can travel faster than light.

Stellar energy, cosmic distances

That blindingly brilliant object that illuminates the daytime sky – our nearest star, the Sun – appears to be the single most important object in the heavens. If it emitted less heat and light than it currently does, humans would struggle to survive; our species would face the bleakest of prospects as the Earth’s oceans froze and most plant and animal life on our planet became extinct. If its heat and light were switched off, human life could not survive at all. If the Sun were a solid lump of coal, it would burn itself to a cinder within a few thousand years. After millennia of speculation, the source of the Sun’s prodigious output of energy (and that of all the stars visible in the sky) was finally explained in 1926 by the British scientist Arthur Eddington. Something far more powerful than simple chemical combustion powers the Sun. We rely on the thermonuclear processes elegantly encapsulated within Einstein’s formula E=mc2 for our continued existence.

As the skies gradually darken after sunset, stars begin to appear. It may seem ironic that the starlight upon which such hopes and dreams for the future are made actually set out on its journey across the galaxy in the remote past – its light may be just over four years old or more than 3,000 years old. Rigil Kent, a star in the constellation of Centaurus, is 4.4 light years away, and the bright star Deneb in Cygnus is 3,200 light years distant. Starlight takes 2.9 million light years to reach us from the nearest big galaxy to our own, the great spiral in Andromeda.

With the exception of the Sun, the stars are too far away to perceive as globes of glowing gas; even when viewed through a powerful telescope, they appear as mere pinpoints of light. Slight variation in colour can be noticed between the stars – some appear white, others bluish, some slightly red. A star’s colour tells us a lot about its physical status – blue stars have intensely hot surfaces, while red stars have comparatively cool surfaces.

Examples of light travel time to the Earth for various objects visible with the unaided eye.

6.5 billion terranauts

We are all separated from the vacuum of space by just a few kilometres of breathable atmosphere. Earth spins on its axis once every 24 hours and revolves around the Sun once a year at a speed of more than 107,000 km/hour, accompanied by the Moon.

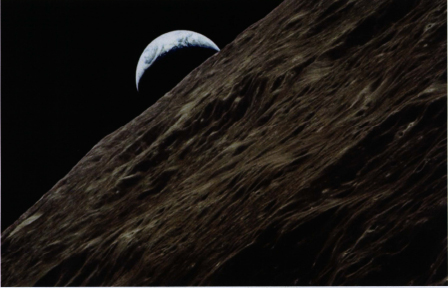

A crescent Earth rises over the rugged lunar surface, photographed by the crew of Apollo 17.

Big blue marble

From his vantage point in the command module of Apollo 8 above the Moon in December 1968, astronaut Jim Lovell described planet Earth as a ‘grand oasis in the big vastness of space’. This grand oasis, a beautiful blue globe, two-thirds of whose surface is covered with water, measures 12,756km across. Our planet is the only place in the Universe known to have life. The fossil record shows that life has clung tenaciously to the Earth’s surface for billions of years, surviving the devastating effects of numerous major geological and cosmic catastrophes. Although mass extinctions of many species of animals have occurred, life – in one form or another – has carried on. Just a few dozen kilometres beneath the Earth’s solid crust is a hot mantle – a zone of molten rock which hasn’t cooled down since the Earth was born some 4.5 billion years ago. The Earth’s crust occasionally splits in a volcanic eruption, allowing this material to erupt onto the surface.

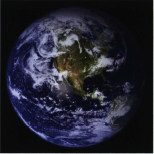

Earth – the grand oasis.

Moon musings

The same gravity that keeps you anchored to the Earth keeps the Moon in orbit. With a diameter about the same as the width of the continental USA, the Moon orbits at an average distance of 384,401km. It took the Apollo spacecraft a few days to traverse the gulf of space between the Earth and Moon, but it would take about a month to get there at the speed of a commercial jet airliner. Second in brilliance to the Sun, the Moon is 400 times smaller than the Sun, but as it is 400 times closer to the Earth, the Sun and Moon appear about the same size in our skies. As the Moon orbits the Earth every month, it goes through a sequence of phases, broadening from a narrow crescent in the evening skies to full Moon in around two weeks, and then becoming narrower again until it is a thin crescent in the morning skies.

At new Moon, the Moon is sometimes seen to move directly in front of the Sun, blocking its light and causing a partial or total eclipse. At full Moon, the Moon sometimes enters the Earth’s shadow and undergoes a partial or total lunar eclipse. Solar and lunar eclipses can be awesome sights.

Fellow wanderers

From little Mercury, whose rocky surface is scorched by the heat of the Sun, to countless deep-frozen cometary chunks from whose surface the Sun appears as a bright point, a remarkable collection of planets, asteroids and comets makes up the Solar System.

Two planetary monarchs compared – Earth, queen of the terrestrial planets, and Jupiter, king of the gas giants.

Meet the neighbours

Our immediate planetary neighbours – Mercury, Venus and Mars – are solid worlds like the Earth. Between Mars and the outer planets of the Solar System lies a zone occupied by countless chunks of rock. These remnants of the Solar System’s formation range from the size of houses to the size of Iceland and are known as asteroids. Four giant planets preside over the outer reaches of the Solar System. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are all swathed in thick layers of mainly hydrogen gas. Jupiter, the largest gas giant, is so big that a thousand Earths could comfortably fit inside its vast volume. Pluto, the outermost planet, is a diminutive world, smaller in fact than our own Moon. More than four light hours from the Sun, Pluto is one of a number of icy worlds at the cold fringes of the observable Solar System. Far beyond the planets, clinging on to the Sun’s gravity to a distance almost half way to the nearest stars, lies an unseen realm of comets known as the Oort Cloud. Cometary visitors from this distant region occasionally speed through the inner Solar System; warmed by the Sun, their icy nuclei emit large amounts of gas and dust, producing celestial spectacles like the magnificent Comet Hyakutake of 1997.

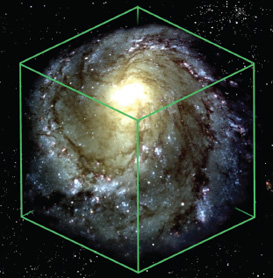

The galactic suburbs

The Sun, attended by its nine major planets and their satellites, along with hundreds of thousands of asteroids and comets, orbits the centre of a vast spiral galaxy of some 300 billion stars called the Milky Way. A middle-aged resident of the galactic suburbs, the Sun is located around 26,000 light years from the galactic centre – about half way from its centre to the edge, within one of the galaxy’s spiral arms. Orbiting the Milky Way at a speed of around 220km per second, the Sun has made around 20 galactic circuits since its birth around five billion years ago.

Measuring around four light years across (if we include the Oort Cloud), the Solar System occupies a tiny part of the Milky Way galaxy, some 100,000 light years in diameter. Indeed, the Sun would not be visible to the unaided eye from a distance of much more than 50 light years. Viewed from the Alpha Centauri system some 4.5 light years away, the Sun would appear as a bright star in the constellation of Cassiopeia.

Our location within the suburbs of the Milky Way spiral galaxy.

Island Universe

On a clear night it’s possible to see hundreds of stars from a rural location. Each one is a relatively nearby member of our home galaxy, whose further reaches dissolve into a glowing band called the Milky Way.

must know

Beginnings

As we probe further into the depths of space, we are looking ever further back in time towards the beginning of the Universe. That beginning, thought to have taken place less than 14 billion years ago, may have been a single ‘Big Bang’ – the explosion of a primeval atom which created spacetime and matter. What caused this to occur, and what took place before the Big Bang, is still unknown.

A grand design

Shaped like a flattened disk with a central bulge, our home galaxy the Milky Way is arranged in a loosely-wound spiral, with a number of curving arms composed of stars and glowing gas clouds. Two nearby small satellite galaxies – the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds – drift some distance beyond the edge of the Milky Way. From our perspective deep within an arm of the galaxy, we see the Milky Way as a glowing band which circles the heavens. Looking towards the bright galactic region in the vicinity of the constellation of Sagittarius, we are peering directly towards the centre of the galaxy. Our view of the actual galactic hub is blocked by dense interstellar clouds of dust and gas, which show up as dark silhouettes against the brighter parts of the Milky Way.

Clouds of interstellar dust and gas in Sagittarius obscure our view of the Milky Way’s bright core.

Around 2.9 million light years away lies the Andromeda Galaxy – the nearest big galaxy to our own, the Milky Way.

Galaxies galore

Only a century ago most astronomers thought that the Milky Way represented the entire Universe. We now know that the Milky Way is just one of billions of other galaxies – some larger, some smaller than our own. The nearest big galaxy to the Milky Way is the Andromeda Galaxy, 2.9 million light years away, a spiral similar to our own. Discernable with the unaided eye on a dark, clear night, the light from that ghostly oval smudge in Andromeda set off long before the first sparks of consciousness flickered within the minds of human beings.

Telescopic surveys have shown us the structure of the wider Universe. Galaxies are arranged in gravitationally-bound clusters and superclusters, immersed in vast clouds of gas. Incredibly, the matter that can be observed telescopically – planets, stars, interstellar gas and dust clouds – make up a small proportion of the matter in the Universe. A staggering 90 per cent is thought to take the form of ‘dark matter’, currently unable to be detected by any telescope. This mysterious stuff is known to exist because its mass produces a detectable gravitational pull on galaxies. What constitutes dark matter is a subject of much debate among astronomers. It may be an entirely new form of matter, quite unlike the stuff we are made of, or it may simply be as yet unobserved ordinary matter such as old failed stars known as ‘brown dwarfs’, or more exotic entities like black holes.

Zooming around the Universe

To get some sense of the size and scale of the cosmos, let’s zoom away from the Earth in giant steps, right out to the very edge of the Universe, pausing to survey the scene before our eyes after each step.

Our home planet, a sphere more than 12,700km across.

The little grey Moon is outshone by its big blue partner.

Earth

Most of the Earth is contained within a 10,000km cube – just 1/30th light second across. From here we can see the blue oceans, the brilliant white clouds and icy polar caps, and the browns and greens of the continents. You may see some large sprawling grey cities during the day, but at night you’ll have no trouble seeing city lights and illuminated roadways. From our high vantage point, the Earth’s atmosphere – our protection against cosmic threats, such as bombardment by meteorites and harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun – appears awfully thin and insubstantial.

Earth-Moon

Virtually a double planet, the Earth-Moon system is contained within a cube 1,000,000km across. Light would take just 3 seconds to get from one side to the other. This view shows the comparative size and brightness of the Earth and the dull grey Moon. The Moon has no atmosphere; no clouds ever appear in the Moon’s skies, rainfall never quenches the dry lunar soil and no rivers flow on its surface. Our only natural satellite has always been dry and lifeless, its surface subject to harsh treatment from cosmic impactors.

Solar System

Contained within a cube of space 10 billion km on each side (8 light hours across) are the orbits of the nine major planets of the Solar System.

The planets are utterly outshone by the brilliant Sun.

Oort Cloud

Viewing a cube of space 1 trillion km (38 light days) on each side, all the major planets in the Solar System are lost in the glare of the Sun, which appears as bright as the full Moon. The inner parts of the distant Oort Cloud of comets are contained within the cube.

At the edge of the Sun’s gravitational domain.

Stellar neighbourhood

A cube measuring 100 x 100 x 100 light years centred on the Sun takes in a sizeable portion of the local stellar neighbourhood, including many of the sky’s brightest stars, from Rigil Kent (4.4 light years away) out to Capella (42 light years away).

Rigil Kent, otherwise known as Alpha Centauri, is the brightest star in the constellation of Centaurus. It is like the Sun in terms of age, size, colour and luminosity, but because it is so near to us it appears as the sky’s fourth brightest star. Alpha Centauri is gravitationally bound to two other stars – a smaller orange star called Alpha Centauri B and a diminutive red dwarf known as Proxima Centauri. Of the three, Proxima is slightly the nearer; at 4.22 light years, it is the nearest star to the Sun. Could planets exist in orbit around Alpha Centauri? Since Alpha Centauri B orbits its brighter neighbour at a distance equivalent to the Sun and Uranus, Alpha Centauri wouldn’t be able to hold on to any planets further away from it as Jupiter is to the Sun, as their orbits would be gravitationally disrupted by Alpha Centauri B.

The Sun, just an ordinary star among its stellar neighbours.

The spiral structure of our galaxy can only be appreciated when viewed from above its plane.

Milky Way

Our home galaxy, the vast spiral of the Milky Way, is enclosed within a cube 100,000 light years across. From this distance we can see only the brightest stars within the galaxy – stars of the Sun’s brightness and dimmer are assumed within a mottled glow, interspersed with the dark silhouettes of opaque dust lanes and glowing clouds of dust and gas.

Our local group of galaxies.

Local galactic group

A cube 10,000,000 light years across will take in the Local Group of galaxies. Only three large spirals dominate the scene – the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy and its neighbour the Triangulum Galaxy. The smaller galaxies dotted around are dwarf and irregular ones. Numerous gravitational interactions between the galaxies of our local group have taken place during the last 12 or more billion years.

Most of the Universe

From our impossible perspective, viewing a cube of space 10 billion light years to each side, most of the objects in the visible Universe can be seen. Each dot represents a cluster of galaxies.

As we look further out into space, we are looking backwards in time. Light from the nearest galaxies in our local group takes a few hundred thousand to several million years to reach us, and we are seeing them as they appeared before homo sapiens sapiens walked the Earth. Galactic clusters and superclusters are arranged in filaments and sheets surrounding huge empty voids. Astronomers work out the distance of far away galaxies by measuring how much light is shifted towards the red end of the spectrum or redshifted. The greater the observed redshift, the greater a galaxy’s distance. Telescopic deep field images have revealed faint galaxies so distant that we see them as they appeared several billion years ago – before life itself developed on Earth.