Universe: The story of the Universe, from earliest times to our continuing discoveries

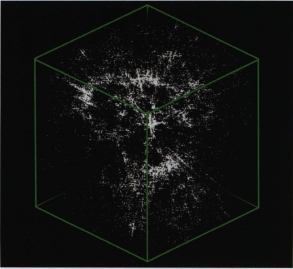

Our picture of the wider Universe is based on redshift measurements.

Want to know more?

Take it to the next level . . .

Other sources. . .

Weblinks. . .

2 In cosmic realms

Humans have been watching the Universe for countless millennia. Records of celestial events go back tens of thousands of years. Our attempts to understand the Universe and our place within it have occupied the thoughts of curious folk since the dawn of civilisation. We take a look back at how our ancestors first interpreted what they saw in the skies above them and how that has evolved into the science we now use today.

Cosmic notions

Our distant ancestors certainly kept a watchful eye on celestial goings-on, for preserved in ancient cave paintings, rock carvings and other human artefacts are indisputable records of a variety of astronomical events.

Observant ancestors

Patterns of dots thought to be star maps and what appears to be an attempt to populate the heavens with figures representing constellations in the form of animals have been discovered at a number of prehistoric sites in various parts of the world. They show an amazing sophistication of thought in our distant ancestors, proving that they were immensely observant of the world around them and the skies above their heads.

Wonderful scenes like this – brilliant Venus and ruddy Mars in Scorpius, rising over the French Alps – have been witnessed by human eyes for countless millennia.

Moon markings

One of the most familiar symbols to be found is the crescent representing the Moon and markings that indicate the monthly lunar cycle of phases. One such lunar calendar of 29 markings – one for each day of the lunar month – has recently been identified in the caves at Lascaux in France, dated to around 15,000 BC. This symbolism, acknowledging the Moon’s importance, is hardly surprising; the Moon’s light will have been of immense value to any culture without the benefit of streetlights and flashlights, in terms of hunting, nocturnal survival and in primitive religions which attached significance to Moon worship and observing the lunar cycles. What many experts consider to be a depiction of the Moon showing the main features discernable with the unaided eye – the dark patches, known as the ‘maria’ – has been discovered in 5,000-year-old rock carvings in prehistoric tombs at Knowth, County Meath in Ireland.

Celestial purpose

Tens of thousands of years ago our ancestors believed the skies had a greater purpose than to be simply admired for their splendour. The heavens were considered to have a purpose; those fixed stellar points of light actually meant something. Those bright objects which appeared to move – the Moon, Sun and the five planets – were imagined to have a special significance. So the skies became incorporated into human affairs, and astrology was born. Unexpected changes in the skies – bright comets, eclipses and novae – were considered to be potent warnings or revelations to humanity.

Carved into Irish rock 50 centuries ago, this set of curves found in the Knowth prehistoric tomb in Ireland may represent the oldest map of the Moon.

Astrology

The notion that the movements of the Sun, Moon and five planets have an influence on the lives of individual people and the course of world events has its roots in ancient concepts and beliefs.

Predictive power

Being able to predict celestial events, from the movements of Venus to eclipses of the Sun and the Moon, appeared to give a great advantage to any society capable of mastering such complex astronomical and mathematical problems. Great civilizations, such as those of ancient Babylon, Egypt and China, attached great importance to observing, recording and predicting heavenly phenomena. Astrologer-priests kept a constant vigil on the skies, ostensibly for society’s well-being and to keep their rulers informed of any celestial portents that might affect the status quo. Astrology was considered such a precious asset that its use without the ruler’s permission was often punishable by execution. Sometimes, either through lack of attention to the skies, sloppy mathematics or just plain bad luck, the astrologers got things wrong – and paid a severe penalty as a result. The ancient Chinese Book of History reports that two court astrologers were executed for having failed to announce a total lunar eclipse in 2136 BC.

Comets were once regarded as celestial omens.

Portents of doom

Of course, not everything in the heavens can be predicted. Even these days, bright novae or supernovae (stars which temporarily brighten far beyond their ordinary brightness), bright comets, fireballs (brilliant meteors) or aurorae (displays of the northern/southern lights) often take astronomers by complete surprise. Although such sights can be awesome to behold, we know how these phenomena are caused and realise that, for the most part, they pose no threat to the Earth or its inhabitants. Only a few hundred years ago, things were very different, and a bright comet might have been regarded as an omen of impending change on the Earth – of natural catastrophe, famine, pestilence, war or a change of ruler.

Astrology may look glamorous, but it is as insubstantial as the paper its predictions are written on.

Pseudoscience

Ancient astrology was practised by making astronomical observations (in an age long before the telescope was invented), so the two subjects of astrology and astronomy were once closely intertwined. Modern forms of astrology, which claim to foretell the destinies of individuals, have often come under close scientific scrutiny, yet have been consistently found to have no provable predictive powers. While many find modern astrology to be entertaining, it has very little basis in science, apart from using certain scientific terms and nomenclature.

Ancient cosmology

Although humans around the world have viewed the same range of celestial phenomena through the ages, our interpretation of them – how they were thought to have been created and what they were believed to have meant – has been immensely varied.

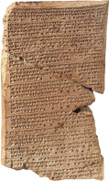

A copy of observations of Venus made in Babylon in 1700 BC is recorded on this clay tablet made at Nineveh in the 7th century BC.

Mesopotamian skies

The science of astronomy can trace its roots back thousands of years to Mesopotamia, a land bordered by the rivers Tigris and Euphrates in modern Iraq.

Fertile minds

Mesopotamia actually means ‘land between two rivers’. The region is also known as ‘the fertile crescent’, its fertility being perhaps the source of the biblical Garden of Eden. Here, from around 4000 BC, the first complex human civilisations grew: first Sumeria, then the kingdoms of Babylon and Assyria.

Omens in the heavens were deemed of tremendous importance to the rulers of ancient Mesopotamia – all events visible in the skies were believed to take place for a reason, and it was the job of the astronomer-priests to note such events, predict them where possible and to interpret their meaning. Astronomical observations were deemed so important that they were preserved on clay tablets imprinted with cuneiform script – a form of writing made with narrow wooden scribes with tapered ends.

A flourishing sky lore also developed in Sumeria, in which ancient myths and legends were projected into the heavens, creating some of the constellations with which we are familiar today. Zodiacal constellations such as Sagittarius, Scorpius, Capricornus, Leo, Gemini and Taurus – areas of the sky through which the Sun, Moon and five planets were observed to travel – were devised by the Sumerians around 5,000 years ago. In addition to having a spiritual significance, the constellations had a practical use – their visibility throughout the year (notably the times of the year when certain constellations were first seen rising or setting) was used to mark agricultural seasons.

Lunar calendar

A calendar based on the Moon’s cycles was used. Each month began with the first sighting of the narrow crescent Moon at sunset, and 12 lunar months made one year. Since 12 lunar months is 11 days short of a solar year (365 days), the Sumerian calendar was synchronized with the solar year by adding a leap month every three or four years.

Babylonian astronomy

The Babylonians adopted and added to ancient Sumerian sky lore, their calendar and scientific knowledge. Hundreds of Babylonian clay tablets noting scientific and astronomical subjects have been discovered. The Babylonians acknowledged the ‘morning star’ and the ‘evening star’ to be a single object –the planet Venus. Lunar eclipses were capable of being predicted with reasonable accuracy.

Babylonian world map, early 5th century BC on a clay tablet, shows a flat, round world with Babylonia at the centre. Eighteen of the animal constellations are named on the tablet.

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptians paid little attention to observing and recording the movements of the Sun, Moon and planets. Instead, special significance was attached to certain bright stars and constellations.

The ceiling of the Temple of Hathor at Denderah (above) depicts a magnificent series of ancient Egyptian constellations (illustrated, top).

Flood warning

By chance, the annual flooding of the River Nile – so vital to irrigating the crops that grew near the river – happened to coincide with the first sighting of Sirius, the sky’s brightest star, as it rose in the east before dawn. It was deemed that the start of each new year would occur with the first new Moon following the reappearance of Sirius. When the system was adopted around 3,000 years ago, the rising of Sirius (known to the Egyptians as Sopdet) just before sunrise took place in early July; it now it takes place around three weeks later because the Earth’s axis points to a slightly different place today than it did in those far off times.

Gods in the sky

A catalogue of the heavens made in 1100 BC lists just five major constellations. In addition, 36 smaller star groups enabled the time to be calculated during the night – helpful tables allowing these calculations to be made have been found inscribed on a number of coffin lids. Osiris, the god of death, rebirth and the afterlife, was represented by the bright, familiar constellation of Orion, and the swathe of the Milky Way represented the sky goddess Nut, who gave birth to the Sun god Ra each day. Circumpolar stars – those stars near the north celestial pole which never set from Egyptian latitudes – were deities known as the ‘Imperishable Ones’.

Pyramid scheme

A collection of large stone slabs recently discovered in Nabta in Egypt (in the Sahara Desert) represent the world’s earliest known astronomically-aligned construction. Dated between 6,000 to 6,500 years old, it is thought that the megaliths were erected by the direct ancestors of the builders of the pyramids, in what was once a fertile area. Climate change caused the residents of Nabta to move eastwards into the Nile Valley, where the great pyramids at Giza were built some time between 2700 to 2500 BC. Astronomy was used to precisely position the pyramids, since their sides are aligned almost exactly north-south and east-west. The fact that they are more accurately aligned east-west suggests that the main positional sighting was made by observing the rising and setting points of a star due east and west; the star Acrab (Beta Scorpii) best fits for the era of the pyramids’ construction. It is likely that the positions of the three great pyramids were meant to reflect the belt stars of the constellation of Orion.

A belief that cosmic events and planetary positions influenced human affairs is remarkably absent throughout most of ancient Egyptian history. Astrology did not figure until the Ptolemaic period, from around the 3rd century BC, when the culture was being influenced by nearby civilisations. Perhaps the best star map depicting astrological constellations can be found on the ceiling of the Temple of Hathor (see left, page 30), constructed in the first century BC.

The three large pyramids at Giza appear to mimic the position of the three belt stars of Orion.

Megaliths and medicine wheels

An awareness of the Universe, and a need to remain tuned in to its cycles prompted ancient cultures in Europe and America to construct earthworks and stone buildings which were aligned with celestial events.

must know

Little is known about the builders of these sites, but it is clear that they attached great importance to observing the Universe and perhaps being able to predict basic celestial events.

Hanging stones

Megalithic monuments dating back 5,000 years can be found across parts of western Europe and the British Isles. Weathered by the elements and damaged by people over the millennia, these battered grey stone circles and other prehistoric monuments make an eerie sight, but their former grandeur can be imagined. Perhaps the most famous of these ancient sites, Stonehenge, on the windswept Salisbury Plain in southern England, dates back to at least 2950 BC. Of unknown religious and ritual significance, Stonehenge and other megalithic constructions appear to have been used to make astronomical sightings of the Sun and Moon and to provide a means to calculate future solar and lunar solar events.

Medicine wheels

Many examples of the ‘medicine wheel’ – a feature commonly constructed from stones laid on the ground which radiate from a raised central cairn to large circular stone rings – can be found across the United States and Canada. Smaller stone circles can often be found nearby these sites. Medicine wheels were constructed and used by native Americans from 4,000 years to a few hundred years ago. Astronomical alignments certainly exist in them, not only connected with the Sun and Moon but connected with the rising and setting points of numerous bright stars, which may have had special significance in native American religion and cosmology.

Ancient Stonehenge keeps a cold and silent vigil on England’s Salisbury Plain.

Ancient China

Far removed from the cradle of western civilisation, China developed its own form of astronomy, creating its own constellations and ideas about the workings of the Universe.

Skies under scrutiny

Over an almost continuous period spanning the 16th century BC to the end of the 19th century AD, court astronomers were appointed to observe and record changes in the heavens. This legacy of almost 3,500 years’ worth of astronomy, in which sunspots, aurorae, comets, lunar and solar eclipses and planetary conjunctions were noted, has provided us with a rich source of reference material.

Ancient Chinese astronomers created a catalogue of stars visible with the unaided eye, divided the skies into constellations known as ‘palaces’ and referred to the brightest star in each palace as its ‘emperor star’, surrounded by less brilliant ‘princes’. In the 4th century BC, the astronomer Shih-Shen catalogued 809 stars and recorded 122 individual constellations.

Instruments to aid naked eye observations were used extensively in ancient China, as they were in the west. In the 1st century, Lo-hsia-Hung constructed an armillary sphere – a device representing the celestial sphere, upon which were marked 365.25 divisions (for the days of the year), and rings for the celestial equator and the meridian. Lo-hsia-Hung’s charming analogy for the Universe likened the Earth to the yolk within an eggshell, stating ‘the Earth moves constantly but people do not know it; they are as persons in a closed boat; when it proceeds they do not perceive it’. In the 15th century an observatory was built on the southeastern corner of the city wall in ancient Beijing, which was equipped with a number of accurately calibrated sighting devices made out of bronze.

Cosmic firecracker

One of the most interesting records dates from 1054 AD and describes the sudden appearance of a ‘guest star’ near the star we know as Zeta Tauri. This bright star, initially brilliant enough to be seen during the daytime and visible to the unaided eye for more than a year, was caused by a supernova – the catastrophic explosion of a massive star. Its remnants are visible today as the Crab Nebula.

Star signs

Astrology played an important role in ancient China. No fewer than 5,000 astrologers resided in 5th century Beijing! Twenty-eight constellations formed the ancient Chinese zodiac, through which the Sun, Moon and planets progressed. Each of the five planets was designated its own element – Mercury, water; Venus, metal; Mars, fire; Jupiter, wood; Saturn, earth. A person’s fate was supposedly determined by the relative position of the five planets, the Moon, Sun and any comets that happened to be in the sky at the time of that person’s birth.

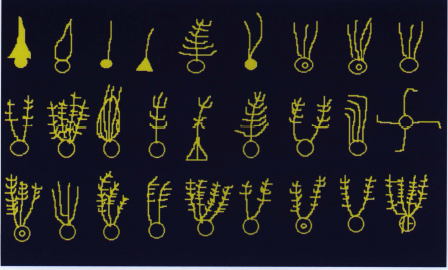

Ancient Chinese astrological classification of comets – known as ‘broom stars’. Each shape was said to foretell a different event.

Ancient Greece

Many concepts about the Universe with which we are familiar today first arose in ancient Greece between 700 BC and 300 AD. Greek philosophers laid the foundations of modern astronomy.

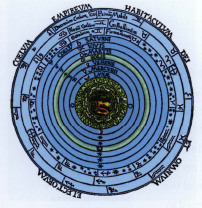

Eudoxus envisaged the Earth at the centre of a series of crystal spheres upon which were fastened the Sun, Moon, individual planets and stars.

Cosmic questioning

The Greeks benefited from the knowledge of the Universe that had been acquired by ancient Mesopotamian astronomers, and much of its ancient sky lore was also adopted and developed into fantastic celestial myths and legends. Quite unlike ancient Mesopotamia, conditions within the Greek civilisation allowed scientific enquiry to flourish. Ancient Greek philosophers were the first to determine the size of the Earth, the distance of the Moon and deduce the cause of solar and lunar eclipses. Greek philosophers enquired into the very nature of the cosmos, as attempts were made to explain objects and phenomena from the very small to the very big, from the basic atomic essence of matter to the structure of the Universe.

Earth-centred Universe

In the 4th century BC, in accordance with Pythagoras’ deduction that the circle and the sphere were perfect figures, Eudoxus devised a complete picture of the Universe, placing our planet at the centre of a nest of 27 concentric transparent celestial spheres to which were attached the Sun, Moon, planets and stars. Each of these Earth-centred spheres rotated around an axis shared with the Earth’s axis. Using 55 spheres, the system was ‘improved’ by Aristotle a century later. It was considered that the Sun, Moon and planets were perfect spherical objects, and circular motions were deemed to be the only paths that could possibly be followed by celestial objects. This notion held sway throughout the entire era of ancient Greek astronomy and persisted through to the renaissance.