Blood, Tears and Folly: An Objective Look at World War II

Blood, Tears and Folly

An Objective Look at World War II

LEN DEIGHTON

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published by William Collins in 2014

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape in 1993

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2014

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Cover design: Antoni Deighton

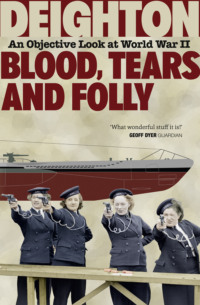

Cover illustration: Gunther Prien’s U-47 (U-Boot Type VIIB built by Germaniaweft Krupp in 1938); cover photograph shows four WRNS with Webley revolvers practising at the pistol range © Imperial War Museum Archive

Source ISBN: 9780007531172

Ebook Edition © February 2014 ISBN: 9780007549498

Version: 2017-03-15

To your children, and ours

‘Death and sorrow will be the companions of our journey; hardship our garment; constancy and valour our only shield.’

Winston Churchill, addressing the House of Commons, 8 October 1940

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Cover Designer’s Note

Illustrations

Introduction

PART ONE: The Battle of the Atlantic

1 Britannia Rules The Waves

2 Days of Wine and Roses

3 Exchanges of Secrets

4 Science Goes to Sea

5 War on the Cathode Tube

PART TWO: Hitler Conquers Europe

6 Germany: Unrecognized Power

7 Passchendaele and After

8 France in the Prewar Years

9 An Anti-Hitler Coalition?

10 German Arms Outstretched

11 Retreat

PART THREE: The Mediterranean War

12 The War Moves South

13 A Tactician’s Paradise

14 Double Defeat: Greece and Cyrenaica

15 Two Side-Shows

16 Quartermaster’s Nightmare

PART FOUR: The War in the Air

17 The Wars Before the War

18 Preparations

19 The Bullets Are Flying

20 Hours of Darkness

21 The Beginning of the End

PART FIVE: Barbarossa: The Attack on Russia

22 Fighting in Peacetime

23 The Longest Day of the Year

24 ‘A War of Annihilation’

25 The Last Chance

26 The War for Oil

PART SIX: Japan Goes to War

27 Bushido: The Soldier’s Code

28 The Way to War

29 Imperial Forces

30 Attack on Pearl Harbor

31 The Co-Prosperity Sphere

Conclusion: ‘Went The Day Well?’

Plate Section

Notes and References

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also By Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Cover Designer’s Note

The story of the Second World War is one of tremendous technological change combined with great human emotion. When I set out to design the covers for this reissue of Len Deighton’s trilogy of Second World War histories, Fighter, Blitzkrieg and Blood, Tears and Folly, I wanted to incorporate both of these elements into a unified design theme that could be used on all three books. The books were among the first to offer a balanced narrative of the war with both sides of the story being represented, and I felt it was essential that the cover designs were similarly complete.

To convey the concept of technological change and development I created illustrations that begin as a set of plans on the back cover and continue across the spine to become a full-colour image of a fighting machine on the front. Many things we take for granted today, such as the mobile phone, microwave and air-traffic control, owe their development to the innovation that took place during the war.

The Second World War affected the lives of every man, woman and child living in Western Europe between 1939 and 1945. Television news has made us accustomed to watching remotely piloted drones waging war from the safety of our living room sofas, uninvolved except for the opinions we choose to express. In contrast I felt it was important to remind readers of the direct participation and sacrifice made by everyone during the war, so I carefully chose photographs of women in a variety of roles.

One such woman was my grandmother, an audacious and inspirational person who left her job as a chef to become a skilled oxyacetylene welder making flame traps for night-fighters. Thousands of women like her, building airplanes, tanks and ships, were immortalized in America by the ‘Rosie the Riveter’ campaign. Britain’s survival during the leanest days of the war owes a debt of gratitude to the Women’s Land Army. These hard-working women succeeded in cultivating every available square foot of land and saved the country from starvation when the U-boat campaign was at its most successful.

The extraordinary women of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry created a secret unit that was dropped by parachute behind enemy lines to undertake espionage work for the Special Operations Executive. Bletchley Park’s work in cracking the ‘Enigma’ codes is well known, and many of the brilliant code-breakers were women. The magnificent women ferry-pilots of the Air Transport Auxiliary flew everything from fast and nimble Spitfire fighters to large and powerful Lancaster heavy bombers, many with battle damage and in need of repair. The Royal Air Force and Royal Navy depended on an army of women radar controllers to manage their operations in the air and at sea.

The contribution to the war made by women was not limited to Britain. In America Jacqueline Cochrane’s famous Women’s Airforce Service Pilots ferried military aircraft, while flight nurses – the unsung heroines of the US Army – provided critical medical attention to wounded soldiers, saving lives on both the European and Pacific fighting fronts. In Russia, too, all the Red Army’s nurses were women. Those serving as front-line medics were also armed and expected to fight alongside their male comrades when not attending to the wounded. Their casualty rate was approximately equal to that of the Red Army infantry. These women demonstrated that they were every bit as willing to help win a war against an enemy that threatened the life they knew. Together they blazed a trail for equality and their lasting contribution to today’s society deserves to be recognized.

Blood, Tears and Folly is a history of the Second World War concentrating on the early years when Britain and her dominions came near to defeat. The German navy’s use of advanced diesel-electric submarines and the four-rotor Enigma machine almost succeeded in starving Britain of raw materials and food. The Type VII is the iconic U-boat of the Battle of the Atlantic. During the early part of the war they were painted in a resplendent three-colour scheme, including a bright red hull below the waterline (they were later painted solid grey to make them less visible). Built by Krupp Germaniawerft in Kiel and launched in 1938, U-47, a Type VIIB commanded by Günther Prien that sank thirty ships including the battleship HMS Royal Oak, begins as a line-drawn plan on the back cover before appearing menacingly in full colour on the front. The front-cover photograph of a group of Wrens qualifying at the pistol range exemplifies Britain’s plucky resolve in the face of extreme adversity. This defiant attitude played an important role in convincing a sceptical United States to support Britain in its war against Germany.

Antoni Deighton, 2013

Illustrations

PLATES

1 Before Munich – Winston Churchill talks earnestly in Whitehall to Lord Halifax, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, after returning from the Continent in March 1938

2 General Wilhelm Keitel, Hitler’s Army Chief of Staff, in conversation with the Führer on a flight to Munich in March 1938

3 Hitler receives Prime Minister Chamberlain at Obersalzberg in September 1938 – the prime move in ‘appeasement’

4 Admirals Erich Raeder and Karl Dönitz planning the German U-boat campaign in the North Atlantic, October 1939

5 Six days after becoming prime minister, Churchill flew to France for talks on the imminent collapse with General Gamelin and General Lord Gort, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, May 1940

6 General Erwin Rommel, after sweeping through France in May 1940, became the notorious ‘Desert Fox’ of North Africa

7 Hitler meets the fascist Spanish dictator General Franco, October 1940

8 General Thomas Blamey, commander of Australian forces in the Middle East, talks to troops just returned from Crete to Palestine

9 General ‘Dick’ O’Connor with the Commander-in-Chief of British forces in the Middle East, General Sir Archibald Wavell, outside Bardia, Libya, January 1941

10 General Sir John Dill, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, with the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden in Cairo, March 1941

11 Prime Minister Churchill inspecting part of Britain’s defences in 1940 with a Tommy gun under his arm

12 Hitler discussing progress of the war with the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, August 1941

13 The German Luftwaffe chief, Field Marshal Hermann Göring, with his deputy Field Marshal Erhard Milch, March 1942

14 Joseph Stalin, the Soviet communist dictator

15 General Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-Chief of all US forces in the Far East, with President Roosevelt

16 General Arthur Percival, commander of Allied troops in Malaya – a clever and experienced leader who was utterly vanquished by a ferocious Japanese force employing 6,000 bicycles

17 Stalin’s trusted General Georgi Zhukov began his career in the Tsar’s dragoons and defeated first the Japanese and then the Germans

18, 19 General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the ‘Tiger of Malaya’, who was forbidden to return to Japan, and Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto, once a student of Harvard University, who master-minded the attack on Pearl Harbor

20 General Hideki Tojo, first Japan’s war minister and then prime minister

FIGURES

1 HMS Dreadnought

2 German U-boat submarine, type V11C

3 HMS Ajax

4 HMS Exeter

5 German Enigma coding machine

6 British shipping losses in the first year of the war

7 Focke-wulf Fw 200C Condor

8 Short Sunderland flying boat

9 Consolidated Catalina flying boat

10 The German battleship Bismarck

11 The US long-range Liberator, used for convoy escort

12 Comparative ship sizes

13 British Lee-Enfield rifle Mk 111

14 Mercedes and Auto-Union racing cars

15 British Bren light machine-gun

16 British, French and German tanks in use at the start of the war

17 Junkers Ju 52/3m transport aircraft

18 German DFS 230 4.1 glider

19 Heinkel He 111 bomber

20 German Mauser Gewehr 98

21 German MG 34 machine-gun

22 Fairey Swordfish from HMS Illustrious

23 German 8.8mm anti-aircraft/anti-tank gun

24 Heinkel He 280 – the world’s first jet fighter, for which neither Milch nor Udet saw any need

25 British Avro Lancaster bomber

26 Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber

27 Supermarine Spitfire and Messerschmitt Bf 109

28 Hawker Hurricane fighter

29 Messerschmitt Bf 110 long-range fighter

30 Dornier Do 17 bomber

31 Junkers Ju 88 bomber

32 The rocket-powered Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet – the fastest aircraft used in the war

33 Germany’s jet-propelled Me 262 – the only jet aircraft to have a significant role in the war

34 Arado 234 ‘Blitz’ bomber (jet)

35 Heinkel 162 ‘Volksjäger’ (jet)

36 Russian Ilyushin 2 Shturmovik

37 Russian T-34 tank

38 Russian machine-pistol PPSh 41

39 Two of the best aircraft of the war the Mitsubishi ‘Claude’ and ‘Zero’ fighters

40 The Japanese aircraft carriers Akagi and Kaga

41 Japanese infantry cyclist

MAPS

1 The pursuit and sinking of the Bismarck

2 North Atlantic convoy escort zones

3 The Maginot Line

4 The invasion of Norway 1940

5 The Westward German armoured offensive

6 German Blitzkrieg and the evacuation of Dunkirk

7 Italy enters the war, June 1940

8 Advance of the Allied XIII Corps along the North African coast, January/February 1941

9 The Mediterranean Theatre 1939–40

10 Battle of Britain – the air battlefield

11 Russian/Japanese battles of 1938–40

12 The expansion of the USSR, 1939–40

13 The ‘buffer states’ between Germany and Russia eliminated by invasions and treaties

14 Russian rail communications

15 Barbarossa: the German Army on the eve of the invasion of the USSR

16 Barbarossa: the first impact

17 German advance towards Moscow, June to December 1941

18 The economic resources of the USSR

19 The German assault on Moscow

20 Petroleum supplies to Britain and Germany 1939

21 World Oil Supplies 1939–45

22 The Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor

23 Japanese invasion routes, and the sinking of Force Z

TABLES

1 Allied shipping losses May–December 1941

2 Relative strengths of the Great Powers in 1939

3 German and Allied casualties, 1940

4 Airmen killed in the First World War

5 Aircraft production 1939–44

6 Average monthly Farenheit temperatures in four Soviet cities

7 Sources of German oil supplies in 1940

8 Japan’s Pearl Harbor carrier attack force

DOCUMENT Guidelines issued for the behaviour of German troops in England as part of the invasion play of 1940

The maps and drawings are by Denis Bishop. Permission to reproduce the photographs is acknowledged with thanks to the following sources: Bibliothek fur Zeitgeschichte, Stuttgart (20); Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin (13); E.C.P. Armées, France (5); Getty Images (1, 14 , 15); Imperial War Museum, London (8, 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 19); Robert Hunt Library/Mary Evans (18); SZ Photo/Mary Evans (2, 3, 6); Ullsteinbild/TopFoto (4, 7, 12).

Introduction

I was lucky to be so early in my studies of the Second World War. Finding participants was not difficult: the eyewitnesses and the men who had done the fighting were mostly still young. The men who had commanded the battles and made the decisions that influenced them were no longer young. My great good fortune was in being able to talk to such senior figures as General Adolf Galland, the Luftwaffe fighter chief, to Major-General Sir Francis de Guingand, the chief of staff to Field Marshal Montgomery, and to General Walther Nehring, who was chief of staff to General Rommel. (General Nehring was kind enough to write an Introduction for my book Blitzkrieg.) I also met with Albert Speer, Hitler’s Minister of Armaments, a remarkable, and usefully frank, source of information about top-level decisions.

When the first edition of this book was ready to go to the printers I sat down with Tony Colwell and Steve Cox, editors who had supported and advised me through the years of writing it. It was the biggest and most demanding work I had ever undertaken and I knew that many of the truths I had uncovered would not bring universal joy. Tony and Steve had been tough critics. It was because they tested and challenged my theories and conclusions that I am now able to look with confidence at this reprinted version which remains as originally written.

***

It is a national characteristic beloved of the British to see themselves as a small cultured island race of peaceful intentions, only roused when faced with bullies, and with a God-given mission to disarm cheats. Rather than subjugating and exploiting poorer people overseas, they prefer the image of emancipating them. English school history books invite us to rally with Henry V to defeat the overwhelming French army at Agincourt, or to join Drake in a leisurely game of bowls before he boards his ship to rout the mighty Armada and thwart its malevolent Roman Catholic king. The British also cherish their heroes when they are losers. The charge of the Light Brigade is seen as an honourable sacrifice rather than a crushing defeat for brave soldiers at the hands of their incompetent commanders. Disdaining technology, Captain Scott arrived second at the South Pole and perished miserably. Such legendary exploits were ingrained in the collective British mind when in 1939, indigent and unprepared, the country went to war and soon was hailing the chaotic Dunkirk evacuation as a triumph.

Delusions are usually rooted in history and all the harder to get rid of when they are institutionalized and seldom subjected to review. But delusions from the past do not beset the British mind alone. The Germans, the Russians, the Japanese and the Americans all have their myths and try to live up to them, often with tragic consequences. Yet Japan and Germany, with educational systems superior to most others in the world, and a generally high regard for science and engineering design, lost the war. Defeat always brings a cold shock of reality, and here was defeat with cold and hunger and a well-clothed and well-fed occupying army as a daily reminder that you must do better. The conquerors sat down and wrote their memoirs and bathed in the warm and rosy glow that only self-satisfaction provides.

Half-finished wartime projects, such as the United Nations, fluid and unsatisfactory frontiers and enforced allegiances suddenly froze as the war ended with the explosion of two atomic bombs. The ever-present threat of widespread nuclear destruction sent the great powers into a sort of hibernation that we called the Cold War. The division of the world into two camps was decided more by the building of walls, secret police and prison camps than by ideology. Expensively educated men and women betrayed their countrymen and, in the name of freedom, gave Stalin an atomic bomb and any other secrets they could lay their hands on. Only after the ice cracked half a century later could the world resume its difficult history.

But not everyone was in hibernation. With the former leaders of Germany, Italy and Japan disposed of as criminals, more criminal leaders came to power in countries far and wide. The Cold War that seemed to hold Europe’s violence in suspense actually exported it to places out of Western sight. The existence of Stalin’s prison camps was denied by those who needed Lenin and Marx as heroes. The massacre of Communists in Indonesia raised fewer headlines than Pol Pot’s year zero in Cambodia, but they were out on the periphery. Newspapers and television did little to counteract the artful management of news at which crooks and tyrants have become adept. Orthodontics and the hair-dryer have become vital to the achievement of political power.

The postwar world saw real threats to the democratic Western ideals for which so many had died. Is the European Community – so rigorously opposed to letting newsmen or the public see its working and decision-making – about to become that faceless bureaucratic machine that Hitler started to build? Is the Pacific already Japan’s co-prosperity sphere? Hasn’t the Muslim world already taken control of a major part of the world’s oil resources, and with the untold and unceasing wealth it brings created something we haven’t seen since the Middle Ages – a confident union of State and Religion?

Britain’s long tradition of greatly overestimating its own strength and skills leads it to underestimate foreign powers. Our Victorian heyday still dominates our national imagination and our island geography has often enabled us to avoid the consequences of grave miscalculations by our leaders. Such good fortune cannot continue indefinitely, and perhaps a more realistic look at recent history can point a way to the future that is not just ‘muddling through’.

In Germany in 1923 runaway inflation produced the chaos in which the Nazis flourished. Today the United States is very close to the position where even the total revenue from income tax will not pay the interest on its National Debt.1 While the Japanese enjoy one of the world’s highest saving rates, Americans are notoriously reluctant to put money into the bank. Furthermore Japan, with a population less than half that of the USA, employs 70,000 more scientists and engineers, uses seven times more industrial robots, and spends over 50 per cent more per capita on non-military research and development.2

Hans Schmitt, who grew up in Nazi Germany, returned to his homeland as an officer of the American army and become professor of history at the University of Virgina, wrote in his memoirs: ‘Germany had taught me that an uncritical view of the national past generated an equally subservient acceptance of the present.’3 It is difficult to understand what happened in the Second World War without taking into account the assumptions and ambitions of its protagonists, and the background from which they emerge. So in each part of this book I shall take the narrative far enough back in time to deal with some of the misconceptions that cloud both our preferred version of the war, and our present-day view of a world that always seems to misunderstand us.

One good reason for looking again at the Second World War is to remind ourselves how badly the world’s leaders performed and how bravely they were supported by their suffering populations. Half a century has passed, and the time has come to sweep away the myths and reveal the no less inspiring gleam of that complex and frightening time in which evil was in the ascendant, goodness diffident, and the British – impetuous, foolish and brave beyond measure – the world’s only hope.