Blood, Tears and Folly: An Objective Look at World War II

For many years the American Rear-Admiral A. T. Mahan’s book The Influence of Sea Power upon History had specified the way in which all sea wars must be fought: by big ships battling to contest sea lanes. But the British would not play this game. Surprising many theorists, the Royal Navy of 1914 refused battle and instead set up a blockade of German ports. The geographical position of the British Isles, and a plentiful supply of ships, persuaded the Admiralty to create barriers across the open water by means of mines and patrols. The Germans responded by a less ambitious blockade of Britain. German warships prowled the sea routes to sink the merchant ships bringing supplies to the British Isles.

Given this strategy, German engineering and the development of the torpedo, it was inevitable that the German navy became interested in submarines. Although they were the last of the major powers to adopt that weapon, the Germans had watched with interest the designs and experiments of other nations. The first German-built submarines were supplied to overseas customers. The Forel, built and tested at Kiel, was supplied to Russia and went by railway to Vladivostok.

The Germans rejected ideas about using submarines for coastal defence, or as escorts for their fleet. They wanted an offensive weapon. This meant longer-range, more seaworthy vessels. Because they considered the petrol engines used by the Royal Navy as too hazardous, their early U-boats used a kerosene (liquid paraffin) engine, but it was the development of the diesel engine that made the submarine a practical proposition. The first production diesel was made in the M.A.N. factory in Augsburg in 1897, and a much improved version was tested in a U-boat in Krupp’s Germania Works in Kiel in 1913. At that time the U-boat was still a primitive device. During the First World War the submarine tracked, attacked and escaped on the surface, its low silhouette making it difficult to spot. It could only hide briefly below the surface but (in a world without asdic, sonar or radar) hiding was enough. The British had more or less ignored the dangers of commerce raiding by submarines because the Hague Convention denied any warship the right to sink an unescorted merchant ship without first sending over a boarding party to decide if its cargo was contraband.

Whatever the rights and wrongs of commerce raiding, any last doubts about the value of torpedo-equipped submarines vanished in 1914, less than two months after the outbreak of war, when Germany’s U-9, commanded by a 32-year-old on his first tour of duty, hit HMS Aboukir with a torpedo and she sank before the lifeboats could be lowered. HMS Cressy lowered her boats to pick up men in the water, but while so doing was hit by a second torpedo. A third torpedo hit HMS Hogue, which also sank immediately. More than 1,600 sailors died. About three weeks later the same rather primitive type of submarine sank the cruiser HMS Hawke.

The development of wireless was changing naval warfare, as it was changing everything else. The admirals seized upon it, for it gave the men behind desks the means of controlling the units at sea. Intelligence officers saw that enemy ships transmitting wireless signals could be located by direction-finding apparatus. Better still, such radio traffic could be intercepted, the codes broken, and messages read.

Intercepted wireless signals played a part in the battle of Jutland in 1916, when Britain’s Grand Fleet and the German High Seas fleet clashed in the only modern battleship action fought in European waters. Lack of flash doors caused HMS Queen Mary to disappear in an explosion, HMS Indefatigable blew up and sank leaving only two survivors, and HMS Lion was only saved because a mortally wounded turret commander ordered the closing of the magazine doors. The loss of the Royal Navy’s three battle cruisers and three armoured cruisers could all be ascribed to their inadequate upper protection.

There were many ways to evaluate the battle of Jutland, and both sides celebrated a victory with all the medals and congratulatory exchanges that victory brings for the higher ranks. In tonnage and human lives lost the British suffered far more than the Germans, but the Royal Navy was more resilient. The British were seafarers by tradition, and regular long-service sailors who fought the battle accepted its horrors in a way that conscripted German sailors did not. Britain’s Grand Fleet took its sinkings philosophically. Within a few hours of returning to Scapa Flow and Rosyth, the fleet reported itself ready to steam at four hours’ notice.

There can be no doubt however that Britain’s technological shortcomings were startlingly evident at Jutland. Once the envy of all the world, Britain’s steel output had now sunk to third place after the United States and Germany, and German steels were of higher quality. Anyone studying the battle had to conclude that German ships were better designed and better made, that German guns were more accurate and German shells penetrated British armour while many of the Royal Navy’s hits caused little damage.

Radio had also played a part in the battle. Helped by codebooks the Russians salvaged from a sunk German cruiser, the men in Room 40 at the Admiralty ended the war able to read all three German naval codes. After the war the work in Room 40 was kept completely secret so that even the official history made only passing mention of it.

By the end of 1916, despite patrols by planes, dirigibles and thousands of ships, U-boats had sunk 1,360 ships. The German U-boat service, which grew to 100 submarines, had lost only four of them to enemy action. The Admiralty stubbornly refused to inaugurate a convoy system, and produced rather bogus figures to ‘prove’ that convoys would block up the ports and harbours. Convoys might never have been started but for the French government insisting that their cross-Channel colliers sailed in convoy. The result was dramatic but the Admiralty remained unconvinced. Perhaps the Admiralty officials thought that escorting dirty old merchant ships was not a fitting task for gallant young naval officers. Whatever their reasons, it took an ultimatum from the prime minister to make them change their minds. (Although later the admirals petulantly said they were about to do it anyway.) When convoys began in May 1917, only ships that could do better than 7 knots, and could not attain 12 knots, were allowed to join them. Losses fell about 90 per cent. The British had come close to losing the war, and before the effect of the convoy system became evident the nerve of the first sea lord, Admiral Jellicoe, broke. On 20 June he told a high-level conference that, owing to the U-boats, Great Britain would not be able to continue the war into 1918. He proved wrong and, thanks to the convoys, the crisis abated.

German U-boats continued sinking passenger ships even after negotiations for peace began on 3 October 1918. The following day Hiramo Maru was sunk off the Irish coast, killing 292 out of the 320 aboard. The following week the Irish mail boat Leinster was torpedoed without warning and torpedoed again while it was sinking: 527 drowned. ‘Brutes they were, and brutes they remain,’ said Britain’s foreign secretary. President Wilson warned that America wouldn’t consider an armistice so long as Germany continued its ‘illegal and inhuman practices’. The U-boat’s Parthian shots had not helped to create a climate suited to negotiations for a lasting peace.

By the time the First World War ended, about 200 U-boats had been sunk, but the submarine menace had been countered only by means of escorted convoys and the use of about 5,000 ships, hundreds of miles of steel nets and a million depth charges, mines, bombs and shells. Yet for those who wanted to find it, the most important lesson of the 1914–18 war in the Atlantic lay in the statistics. In the whole conflict only five ships were sunk by submarines when both surface escort and air patrol was provided, and this despite the fact that no airborne anti-submarine weapon had been developed.

2

DAYS OF WINE AND ROSES

The man who with undaunted toils

Sails unknown seas to unknown soils

With various wonders feasts his sight:

What stranger wonders does he write!

John Gay, ‘The Elephant and The Bookseller’

By the end of the First World War Britain was exhausted, financially bankrupt and in debt to the USA. The Empire, having made a selfless and spontaneous commitment to the war, no longer wanted to be ruled by men of Whitehall. British leaders, both civilian and military, had proved inept in conducting a war which, had the United States not entered it, Germany might well have won.

In 1922, Britain formally acknowledged her declining power. Since Nelson’s day Britain’s declared policy was to have a navy as strong as any two navies that could possibly be used against her. Even into the 1890s Britain was spending twice as much on her fleet as any other nation. With the Washington treaty of 1922 such days were gone. The politicians agreed that the navies of Britain, USA and Japan should be in the ratio of 5:5:3. Britain also accepted limitations upon the specifications of its battleships, and promised not to develop Hong Kong as a naval base and to withdraw altogether from Wei-hai-wei, China. In conforming to the treaty, the Royal Navy scrapped 657 ships including 26 battleships and battle-cruisers. One history of the British Empire comments: ‘So ended Britain’s absolute command of the seas, the mainstay and in some sense the raison d’être of her Empire.’1

After the First World War, the surrendered German fleet sailed to Scapa Flow, between Orkney and the Scottish mainland. There, in a gesture of defiance, they scuttled all their ships. This provided Germany with a chance to start again with hand-picked personnel and modern well-designed ships, while the victorious nations were patching up their old ships to save money.

The treaty of Versailles stipulated that Germany’s navy must be kept very small but in June 1935, acting without reference to friends or enemies, the British government signed an Anglo-German naval agreement permitting Hitler to build a substantial navy, up to 35 per cent as strong as the Royal Navy, and include battleships, virtually unlimited submarines and eventually cruisers and aircraft-carriers.2

This notable concession to Hitler’s belligerence encouraged him to ever more reckless moves and deeply offended Britain’s closest ally France. It went against all Britain’s international undertakings and, in grossly breaching the peace treaty, nullified it. The first lord of the Admiralty said: ‘the naval staff were satisfied and had been anxious to bring about an agreement’. Stabilization of Anglo-German naval competition would release RN ships to distant waters. Perhaps the British politicians – and the men in the Admiralty who advised them – believed that showing good will towards the Nazis would bring lasting peace. One suspects that it revealed some calculation in the minds of Britain’s leaders that a more powerful Fascist Germany would keep Communist Russia contained.

Significantly perhaps, the Reichsmarine was renamed Kriegs-marine and the Germans began building immediately. Germany’s four biggest battleships, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Bismarck and Tirpitz, which were later to give the Royal Navy so many sleepless nights, were laid down as an immediate result of this treaty. The following year Germany agreed – in the London Submarine Protocol of 3 September 1936 – that it would adhere strictly to the international prize law, which provided for the safety of merchant ship passengers and crews in time of war.

In 1937 came a supplement to the 1935 treaty. A German naval historian, Edward P. von der Porten, has described it as ‘a German attempt to convince the British of sincerity’. The Germans affirmed that they would build no battleships bigger than 35,000 tons. The Bismarck and Tirpitz, then in production, were 41,700 and 42,900 tons respectively. The extra tonnage, explained U-boat C-in-C Karl Dönitz after the war, was for ‘added defensive features’. In fact the extra size was due to Hitler specifying 15-inch guns instead of the previous 11-inch ones.

While German shipyards were producing these impressive warships Britain’s shipbuilding industry was antiquated and inefficient. It had suffered from the strikes and slumps that other British industry knew well. Yet while Britain’s merchant navy, although still large, was in decline, no such decline befell the bureaucrats of Whitehall. In 1914, with 62 capital ships in commission, the Admiralty employed 2,000 officials. By 1928 – with only 20 capital ships in commission, and the Royal Navy officers and men reduced from 146,000 to 100,000 – there were 3,569 Admiralty employees. Although the Washington naval treaty prevented any increase in Britain’s naval forces, there were by 1935 no less than 8,118 Admiralty staff on the payroll.3

Germany had ended the war without ships or shipbuilding facilities but the creation of a strong navy and a merchant fleet had been decided upon long before Hitler came to power. In the summer of 1929 these plans bore fruit as the ocean liner Bremen snatched the Atlantic Blue Riband from the elderly British liner Mauretania. The following year Bremen’s sister ship Europa took the record. Both German liners displaced about 50,000 tons, with top speeds of about 27 knots. These products of German shipyards were given energetic publicity by the Nazi propaganda machine. Germany had staked its claim to the Atlantic sea routes and intended to remain there.

Equipping for war

On Sunday 3 September 1939 Britain declared war on Germany. Although there were no treaty obligations between Britain and the Dominions, Australia and New Zealand also declared war at once. The Canadians declared war on Germany after Britain (but were later to declare war on Japan before Britain). South Africa followed after some fierce parliamentary debate, and the Viceroy took a similar decision for India seemingly without reference to anyone. Virtually the whole of the Empire and Commonwealth, from Ascension Island to the Falklands, joined the mother country. A newly independent Ireland remained neutral and was represented in Berlin throughout the war by an ambassador accredited in the name of King George.

In the course of time, 5 million fighting troops were raised from these overseas countries, with India contributing the largest volunteer army that history had ever recorded.4 But warships were in scarce supply. The navy was still regarded as the factor which both bound the countries of the Empire and protected their sea routes. So, for Britain’s Royal Navy, the war was a global one right from the first hour of hostilities.

Britain went to war with a Royal Navy that was highly skilled and totally professional, although its officers and men were poorly educated when compared with men of the other industrialized nations. Most of its 109,000 sailors had joined as boys aged sixteen, and most of its 10,000 officers as thirteen-year-old cadets. Steeped in tradition, its ratings wearing curious old uniforms which could not be put on without help, the navy provided a tot of rum each day for every man, and the fleet retained corporal punishment long after the other services had abolished it.

When wartime’s compulsory military service first sent civilians to sea, they regarded this narrow-minded, time-warped community with awe. They took it over, and changed it for ever. Soon the regular sailors with their distinctive rank badges were outnumbered by HO (Hostilities Only) ratings and RNVR (Volunteer Reserve) officers with ‘wavy-navy’ rings on their cuffs. By the middle of 1944 the wartime navy totalled 863,500 personnel of whom 73,500 were WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service). The sailors who fought and won the Atlantic battle were in the main civilians.

When war started the Admiralty was calm and confident. With fifteen battleships, of which thirteen had been built before 1918 (and ten of these were designed before 1914), and six aircraft-carriers of which only HMS Ark Royal was not converted from other ships’ hulls, it knew exactly what sort of war it was going to fight. Unfortunately Germany’s naval staff, the Seekriegsleitung (SKL), had a different rule book.

A less parsimonious British government or a more realistic Royal Navy might have expected the Germans to break their agreements, but the interwar years had been noted for self-delusion, and the admirals did not readily learn lessons. The Royal Navy seemed indifferent to the threat of air attack. Its multiple pom-pom anti-aircraft guns had proved completely ineffective, but only when war was imminent were Swedish Bofors and Swiss Oerlikon guns put into production.

A closed eye had been turned to the potential of the submarine. With lofty disdain, most Royal Navy officers regarded the submarine service as a refuge for officers of low ability. Submarines participating in fleet exercises were always ordered to withdraw during the hours of darkness. Anyone who suggested that in a future war the enemy might not be willing to withdraw during the hours of darkness was told that the miracle apparatus asdic could counter submarines.

Asdic (later named sonar) was a crude device first introduced at the end of the First World War, although never used operationally in that war. Mounted under a ship’s hull, it emitted sound waves and picked up their reflections to detect submarines. Always demonstrated in perfect weather by well-rehearsed crews, it enabled a confident Admiralty to declare the U-boat to be a weapon of the past. By 1937 the Naval Staff said that ‘the submarine would never again be able to present us with the problem we were faced with in 1917’. Even if the Admiralty’s assessment of asdic had been right, there were only 220 warships equipped with it, while the British merchant service had 3,000 oceangoing ships and 1,000 large coasters to be protected.

The range of the asdic was a mile at best. It could not pierce the layers of differing temperature and salinity that are commonly found in large bodies of water. Nor could it be used by a ship steaming at more than 20 knots, or in rough weather. It was useless in locating a surfaced submarine and did not reveal the depth of a submerged one. All of these shortcomings could benefit a skilful U-boat commander, and it might have been remembered that by the end of the First World War attacks by surfaced U-boats had become the favoured tactic.

Admirals everywhere prefer big ships. The United States navy lined them up in Pearl Harbor and, even in the middle of the war, German admirals were still telling each other that the battleship was the most important naval weapon and pressing for a programme to build more and more of them. So the British navy, like the United States navy, began the war with plenty of expensive battleships for which there was little or no need and a grave shortage of small escort vessels.

Canada wanted to make a contribution to the war without having its soldiers decimated at the commands of British generals on some new ‘western front’. It elected to concentrate on ships, which could be kept under its own control. The Canadian navy started a construction programme exclusively devoted to escort vessels – corvettes and frigates – to protect the Atlantic traffic. The corvettes were slow and seaworthy, although the way in which they rolled and wallowed from wave top to wave top made crewing them one of the war’s most queasy assignments. Nevertheless by May 1942 Canada had 300 ships – a magnificent achievement.

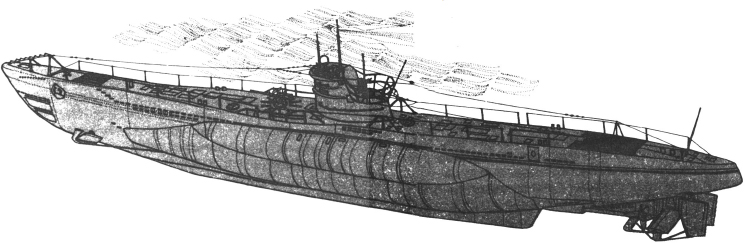

FIGURE 2

German submarine U-boat, type V11C

The U-boat

Since the First World War, submarine design had improved only marginally, and then chiefly in greater hull strength. This enabled them to dive far deeper, and provided escape for many U-boats under attack. (Due largely to inter-departmental squabbles, it took some time before British depth charges were designed for deep water use.) Although more efficient electric batteries enabled submarines to stay submerged longer, they still spent almost all their time on the surface, submerging only to escape attacks from the air or avoid very rough seas.

A submarine of this period consisted of a cylindrical pressure hull like a gigantic steel sewer pipe. To this pipe, a stern and bow were welded and the whole vessel was clad in external casing to give it some ‘sea-keeping capability’, although submarines could never be manoeuvred like ships with regular hulls. A casing deck and a conning tower – what the Germans called an ‘attack centre’ – was added to the structure. Directly below the conning tower was the ‘control room’ where the captain manned the periscope. The tower was given outer cladding to provide some weather protection to men standing there, as well as some measure of streamlining when the boat went underwater. An electric motor room and an engine room with supercharged diesels of about 3,000 bhp were positioned well aft for the sake of sea-keeping and to cut diving time. The great bulk of a submarine was below the water-line, and visitors going below are always surprised to discover how big they are, compared with the portion visible above water. For instance, the long-range Type IXC U-boat that displaced 1,178 tons submerged would still displace 1,051 tons when on the surface.

There were two basic types of German U-boat used operationally in the Atlantic campaign, the big long-range Type IX and the smaller Type VII, which was the standard German U-boat of the Second World War.5 The VII typically had a displacement of 626 tons, a crew of four officers and forty-four ratings (enlisted men), and carried about fourteen 21-inch torpedoes. Four tubes faced forward and one aft. All the tubes were kept loaded and when they had been fired, the awkward business of reloading had to be done. On the surface the diesel engines gave a range of 7,900 nautical miles at 10 knots. If they pushed the speed up to 12 knots it would reduce their range to 6,500 nautical miles. In an emergency the diesels could give 17 knots for short periods. With a fully trained crew a Type VII dived in thirty seconds and when submerged used electric motors. The rechargeable batteries could go for about 80 nautical miles at 4 knots. Maximum speed underwater was reckoned to be 7.5 knots, depending upon gun platforms which obstructed the water flow. Most reference books give manufacturer’s specification speeds which are faster than this.

The whole purpose of the submarines was to fire torpedoes. These big G7 – seven metres long – devices were no less complicated than the submarine itself, and in some respects exactly like them. They were treated with extraordinary care. Each torpedo arrived complete with a certificate to show that its delicate mechanisms had been tested by firing over a range. It had been transported in a specially designed railway wagon to avoid risk of it being jolted or shaken. One by one, with infinite concern, the ‘eels’ were loaded into the U-boat, which was usually moored inside a massive concrete pen. From then onwards, all through the voyage, each and every eel would be hung up in slings every few days, so that the specialists could check its battery charge, pistols, propellers, bearings, hydroplanes, rudders, lubrication points and guidance system.

To make an attack it was necessary to estimate the bearing and track of the target. Usually the submarine was surfaced, and the captain used the UZO (U-Boot-Zieloptik) which was attached to its steel mounting on the conning tower. This large binocular device had excellent light-transmission capability, even in semi-darkness, and from it the bearing, range and angle of the target vessel was sent down to the Vorhaltrechner. This calculator sent the target details to the torpedo launch device, Schuss-Empfänger, and right into the torpedoes, continuing to adjust the settings automatically as the U-boat moved its relative position. By means of these instruments the U-boat did not have to be heading for its target at the moment of launching its torpedo. The torpedo’s gyro mechanism would correct its heading after exiting the tube. Thus a ‘fan’ of shots, each on a slightly different bearing, could be fired without turning the boat. This device was coveted by British submarine skippers who aimed their torpedoes by heading their submarines towards the target.