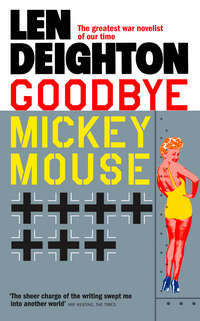

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

‘Nearly there now,’ said Farebrother, more to himself than to his friend. Separation from Charlie would be a bad wrench. They’d been together since they were aviation cadets learning to fly on old Stearmans, and it was easy to understand why they’d become such good friends. Both were calm, confident young men with easy smiles and quiet voices. More than one member of a selection board had said they were not aggressive enough for the ritual slaughter now taking place daily in the thin blue skies above Germany.

‘Why didn’t I bring my long underwear?’ said Charlie Stigg, letting the flap close against the chilly air.

‘It’s nearly Christmas,’ said Farebrother.

‘I guess almost anything will be better than teaching Cadet Jenkins to land an AT-6.’

‘Almost anything will be safer,’ said Farebrother. ‘Even Norwich on a Saturday night.’

‘You know why I stopped going to the Saturday-night dances?’ said Charlie Stigg. ‘I couldn’t face another of those girls telling me I looked too young to be an instructor.’

‘They didn’t mean anything by that.’

‘They thought we were ducking out of the war—they figured we volunteered to be flying instructors.’

‘The kind of girl I met at the dances didn’t even know there was a war on,’ said Farebrother.

‘Norwich,’ said Stigg. ‘So that’s how you pronounce it; I guess I’ve been saying it wrong. Yeah, good. Come over there and see me, Jamie, it sure will cheer me up.’ The truck stopped and they heard the driver hammering on his door to signal that this was Stigg’s destination, the Red Cross Club.

‘Good luck, Charlie.’

‘Look after yourself, Jamie,’ said Charlie Stigg. He threw his bag out onto the ground and climbed down. ‘And a merry Christmas.’

It wasn’t fair. Charlie Stigg had been hardworking and conscientious enough to master the complications of flying multi-engined aircraft, so when they finally let him go to war they turned down his application for fighters and sent him to a Bomb Group. Farebrother deliberately flunked his conversion to twins and got the assignment that Charlie so desperately wanted. It wasn’t fair, war isn’t fair, life isn’t fair.

He suffered a pang of guilt as he watched Charlie staggering up the steps of the club under the weight of his pack, and then, with the heartlessness of youth, dismissed the feeling from his mind. Farebrother was going to be a fighter pilot; he was the luckiest guy in the world.

‘Is this the truck for Steeple Thaxted?’ a voice called from the darkness.

‘That’s the way I heard it,’ said Farebrother.

An officer in a waterproof mac followed by half a dozen enlisted men climbed into the truck. Realizing that Farebrother was an outsider, they drew away from him as if he were the carrier of some contagious disease. The truck started and the officer lit a cigarette and then offered one to Farebrother, who declined and then asked, ‘What’s it like at Steeple Thaxted?’

‘Ever been in the Okefenokee Swamp when the heating was off?’

‘That bad?’

‘Picture an endless panorama of shit with tents stuck in it and you’ve got it. Whenever I meet a new dame at a dance, the first thing I ask her is if she’s got a bathroom with hot water.’ He drew on his cigarette, well aware of his audience of EMs. ‘Of course, this being England, she usually hasn’t got a bathroom.’ One of the men chuckled.

‘You’re living in tents in this weather?’ said Farebrother.

The officer prodded Farebrother’s bag with the toe of his shoe and pushed at it until he revealed the stencilled lettering on the side. ‘A fly-boy, are you?’ He tilted his head to read the name.

‘I’m a pilot,’ said Farebrother.

‘Captain J. A. Farebrother,’ the officer read aloud. ‘A captain, eh? This is a second tour, or have you been in the Pacific?’

‘I’ve been an instructor back home,’ said Farebrother apologetically.

The officer sniffed and wiped his nose with a dainty handkerchief obviously borrowed from a lady friend. ‘I’ve got a cold,’ he said as he put it away. ‘My name’s Madigan, Vincent Madigan. I’m a captain—Group Public Relations Officer. I guess you’re assigned to Colonel Badger’s 220th Fighter Group?’

‘Right.’

‘If you’re a flyer, you’ll be all right. That son of a bitch Badger has no time for anyone who isn’t a flyer.’ There was a soft growl of agreement from one of the other men.

‘Is that right?’ Farebrother looked round at the huddled figures. There was the odour of warm bodies in wet overcoats and the pungent smell of sweet American tobacco. The men were obviously coming back from pass and would go straight to their duties in the morning. They were waiting for Madigan to stop talking so they could catch up on their sleep.

‘Mud, shit and tents,’ reaffirmed Madigan. ‘And the local Limeys hate us more than they hate the Krauts.’

‘Hold it there,’ said Farebrother. ‘My mother was English. The way I see it, we’re in the war together; no sense in partners feuding.’

Madigan nodded and puffed at his cigarette. ‘They gave you the lecture, then.’ A sergeant sitting next to Madigan rested his head back against the canvas side of the truck. There was a cigarette in his mouth and, as he inhaled, the light from it illuminated a face with a large blunt moustache, a soft garrison cap tipped down to his half-closed eyes, and the collar of his overcoat wrapped around his ears. He pulled the collar tighter to close out Madigan’s voice, but Madigan didn’t notice. ‘You’ll find out,’ he promised. ‘You’re still on the crusade. Most of us started out that way. But you get Colonel Badger chewing your ass out. You get the Limeys screwing your last dollar out of you and then spitting in your eye. You get memos telling you how the top brass are figuring new ways to get us all killed…Suddenly maybe you’ll start thinking the Krauts aren’t so bad.’

The truck jolted as it went over some bomb-damaged road surface. Through the open canvas at the back they saw a British soldier with a flashlight waving the traffic past. Behind him there was a large red sign: ‘Danger. Unexploded Bomb.’

‘Watch out, mate,’ the soldier called. ‘The red alert is still on.’ The driver grunted his thanks.

‘Even if things are as rotten as you say, what can we do about it?’ said Farebrother.

Madigan threw his half-smoked cigarette into the darkness, where it made a sudden pattern of red sparks. He leaned forward and Farebrother smelled the whisky on his breath. ‘There are ways, Farebrother, my boy,’ he said flippantly. ‘There are Swedish airfields packed wing tip to wing tip with Flying Fortresses and B-24s. There must be room there for a factory-fresh Mustang fighter plane.’ He leaned back in his seat, watching Farebrother catch the effect of his words. ‘Some flyers out there over the sea get a sudden hankering to make a separate peace. They steer north to the big blonde girls, farm butter and central heating. You’ll be tempted, Farebrother, old buddy.’

Nervously Farebrother reached for his own cigarettes and lit one. He took a long time doing it. He didn’t want to talk any more with this drunken officer.

But when the cigarette was lit, Madigan said, ‘You’ve got a nice lighter there, Captain. Mind if I take a closer look?’ When it passed to him Madigan silently read the engraved ‘To Jamie from Dad’ and then clasped it tight in his hands.

‘Women are all the same,’ said Madigan. He was speaking more quietly now and with a fervour his earlier conversation had lacked. ‘I was in love this time. Ever been in love, Farebrother?’ It was not a real question and he didn’t wait for an answer. ‘I offered to marry her. Last night I dropped in unexpectedly and I find her in the sack with some goddamned infantry lieutenant.’ He tossed the lighter into the air. ‘She’s probably been two-timing me all along. And I was in love with the little whore.’

Farebrother murmured sympathetically and Madigan tossed the lighter to him.

‘You’ll be all right,’ said Madigan. ‘Your reflexes are okay for three o’clock in the morning. And any guy who goes to war carrying a solid-gold lighter is well motivated for survival. From Dad, eh?’

Farebrother smiled and wondered what Captain Madigan would say if he knew that Dad was one of the top brass who were figuring new ways to get them all killed.

Lieutenant Colonel Druce ‘Duke’ Scroll was the Group Administrative Executive Officer. He was a fussy thirty-nine-year-old who made sure everyone knew he’d graduated from West Point long before most of the other officers were out of high school. The Exec dressed like an illustration from The Officer’s Handbook. His wavy hair was always neatly trimmed and his rimless spectacles polished so that they shone.

‘What time did you arrive, Captain Farebrother?’ His eyes moved quickly to look out of the window. Two aircraft were parked on the muddy grass, their green paint shiny with the never-ending rain. Some men were huddled against the control tower, the outer walls of which were patchy from a half-finished paint job. Behind it the airfield was empty, its grass darkened by the sunless weeks of wintry weather.

‘A little after eight o’clock this morning, sir.’

‘Transport okay? And you got breakfast, I trust.’ The Exec was bent over his desk, his hands flat on its top, reading from an open file. There was no solicitude apparent in the questions. He seemed more interested in double-checking the motor pool and the mess staff than in Farebrother’s welfare. He looked up without straightening his body.

‘Yes, thank you, sir.’

The Exec banged a hand down on the bell on his desk, like an impatient hotel guest. His sergeant clerk appeared immediately at the door.

‘You tell Sergeant Boyer that if I see him and the rest of those lead swingers goofing off just once more, he’ll be a buckass private in time for lunch. And you tell him I’m looking for men to do guard duty over Christmas.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said the sergeant clerk doubtfully. He looked out of the window to discover what the Exec could see from here. ‘I guess the rain is pretty heavy.’

‘The rain was heavy yesterday,’ said the Exec, ‘and the day before that. Chances are it will be heavy tomorrow. Colonel Badger wants the tower painted by tonight and it’s going to be done by tonight. The Krauts don’t close down the war every time it rains, Sergeant. Not even the Limeys do that.’

‘I’ll tell Sergeant Boyer, sir.’

‘And make it snappy, Sergeant. We’ve got work to do.’

The Exec looked at Farebrother and then at the rain and then at the papers on his desk. ‘When my sergeant returns he’ll give you a map of the base and tell you about your accommodation and so on. And don’t kick up a fuss if you’re sleeping on the far side of the village in a Quonset hut. This place was built as an RAF satellite field, it wasn’t designed to hold over sixteen hundred Americans who want to bathe every day in hot water. The Limeys seem to manage with a dry polish—they think bathing weakens you.’ He sighed. ‘I’ve got over three hundred officers here. I’ve got captains and majors sleeping under canvas, shaving in tin huts with mud floors and cycling three miles to get breakfast. So…’ He left the sentence unfinished.

‘I understand, sir.’

Having finished his well-rehearsed litany, Colonel Scroll looked at Farebrother as if seeing him for the first time. ‘The commanding officer, Colonel Badger, will see you at eleven hundred hours, Captain Farebrother. You’ve just got time enough to shave, shower and change into a clean class A uniform.’ He nodded a dismissal.

It seemed a bad moment for Farebrother to tell him that he had already showered in the precious hot water, shaved, and was wearing his newest and cleanest uniform. Farebrother saluted punctiliously, and then performed the sort of about-face that was said to be de rigueur at West Point. The effect was not all he’d hoped for; he lost balance performing what the Basic Field Manual describes as ‘…place the toe of your right foot a half foot length in rear and slightly to the left of your left heel. Do not move your left heel.’ Farebrother moved his left heel.

Everything good or bad about the base at Steeple Thaxted during those days was largely due to the Group Exec. It was Duke Scroll who—like all executive officers throughout the Air Force—made life a pleasure or a pain, not only for the flyers but also for the sheet-metal workers, the parachute packers, and the clerks, cooks and crew chiefs who made up the three Fighter Group squadrons, and the Air Service Group, which supplied, maintained, policed and supported them.

The Exec stood behind Colonel Daniel A. Badger, station commander and leader of the Fighter Group. They were a curious pair—the prim, impeccable Duke and the restless, red-faced, squat Colonel Dan, whose short blond hair would never stay the way he combed it and whose large bulbous nose and pugnacious chin never did adapt easily to the strict confines of the moulded-rubber oxygen masks the Air Force used.

Colonel Dan rubbed the hairy arms visible below the shortened sleeves of his khaki shirt. It was a quick nervous gesture, like the few fast strokes a butcher makes on a sharpening steel while deciding how to dissect a carcass. In spite of the climate he never wore long sleeves and only put on his jacket when it was really needed. His shirt collar was open, ready for his white flying scarf—‘ten minutes in the ocean and a GI necktie will shrink enough to strangle you.’ Colonel Dan was always ready to fly.

‘Captain Farebrother!’ The Exec announced him as if he were a guest at a royal ball.

‘Yeah,’ said Colonel Dan. He went on looking at the sheet of paper that the Exec held before him, as if hoping that some more names would miraculously appear there. ‘Just one of you, eh?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Farebrother, restraining an impulse to turn round and see.

Colonel Dan ran a hand across his forehead in a movement that was intended both to mop his brow and to push back into position his short disarranged hair. ‘Do you know what I’ve had to do to get this Group equipped with those P-51s out there?’ He didn’t wait to hear the answer. ‘No officer on this base has tasted whisky in weeks! Why? Because I’ve used their booze ration to bribe the people who shuffle the paperwork at Wing, Fighter Command, and right up to Air Force HQ. In London a black-market bottle of scotch can cost you four English pounds. You can figure the money, I suppose, so you can figure what it’s cost to get those ships.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Farebrother. He’d understood the British currency ever since parting with two pounds to get his travel-creased uniform sponged and pressed in time to wear it at this interview.

‘I was hanging around Wing so much,’ went on Colonel Dan, ‘that the General thought I was dating his WAC secretary.’ He chortled to show how unlikely this would be. ‘I bought lunches for the Chief of Staff, and had my workshops make an airplane model for the Deputy’s desk. When I finally discovered that the guy who really makes the decision was only a major, I spent over a month’s pay taking him to a nightclub and fixing him up with a girl.’ He grinned. It was difficult to decide how much of all this was intended seriously, and how much was an act he put on for newly arrived officers.

‘So I get my airplanes, and what happens? I lose six jockeys in a row. Look at this manning table. One of them’s got an impacted wisdom tooth, one’s hurt his ankle playing softball, and one’s got measles. Can you beat that? The Flight Surgeon tells me…’ He tapped the papers on the table as if to prove it. ‘He tells me this officer’s got measles and can’t fly.’ He looked at Farebrother. ‘So just when I get three squadrons of Mustangs here ready to fly, I’m short of men. And what do they send me? Not the eleven lieutenants the T/O says I’m supposed to have from the replacement depot, but one lousy flying instructor—’ He raised his hand. ‘No offence to you, Captain, believe me. But goddamn it!’ He banged on his desk in anger. ‘What do you think they want me to do, Duke?’ The CO twisted round in his swivel chair to look up at his Exec. ‘Do they want me to set up Captain Farebrother in a dispersal hut on the far side of the field and have him train a dozen pilots for me? Could that be the idea, Duke?’

Colonel Dan scowled at Farebrother and tried without success to stare him down. Finally it was the CO who looked down at his paperwork again. ‘Fifteen hundred flying hours and an unspecified amount of pre-service flying,’ he read aloud. ‘I suppose you think that’s really something, eh, Captain?’

‘No, sir.’

‘We’re not flying Stearman trainers in neat little patterns over the desert, following the train tracks home when we get lost, and closing down for a long weekend whenever a cloud appears in the sky.’ He stabbed a finger at the window. ‘See that pale grey shit up there? It’s two thousand feet above the field and it’s ten thousand feet thick. And you’re going to be flying an airplane up through that stuff…an airplane you never dreamed existed even in your worst nightmare. These P-51 Mustangs are unforgiving s.o.b.s, Captain. No dual controls on these babies…just a mighty big engine with wings attached. For the first few rides they’ll scare you half to death.’

Colonel Dan banged the file shut. ‘We’re stood down right now, as you can see. Plenty of airplanes for you to try your hand on. Most of my pilots are on pass—flat on their faces drunk in some Piccadilly gutter, or trying to buy their pants back from some Cambridge whore. Am I right, Colonel Scroll?’

‘Most probably, sir,’ said the matronly Exec, moving one lot of papers away before placing a new pile in front of the CO. His face was expressionless, as if he were playing the role of butler to a playboy he didn’t like.

‘Get yourself a helmet and a flight suit, Captain,’ said Colonel Dan. ‘And take my advice about logging some hours on a P-51 before the Group’s assigned to its next mission.’ He scratched his arm again. ‘One of my flight commanders is still waiting for his captain’s bars, and that boy has five confirmed kills. How do you think he’s going to feel when he sees you practising wing-overs with those shiny railroad tracks on your collar? Having you turn up means he’ll wait even longer for promotion. You know that, don’t you?’

‘Yes, sir.’

The Colonel touched the edges of the papers the Exec had placed in front of him. Then, as he looked up, his eyes focused upon Farebrother and dilated with amazement. ‘Captain Farebrother,’ he said in a voice which suggested that all the foregoing had been part of some other conversation, ‘may I ask what, in God’s name, you are wearing? Is that a pink jacket?’ His voice croaked with indignation.

‘At my previous assignment it was customary for instructors to have jackets made up in tan gabardine, like the regulation pants.’

‘I swear to you, Farebrother,’ said the Colonel with almost incoherent vehemence, ‘that if I ever see you wearing that pansy oufit again…’ He rubbed his mouth as if to still his own anger.

‘You make sure you wear the regulation pattern uniform, Captain,’ said the Exec. ‘The enlisted men have been getting tailors’ shops to make up all kinds of cockamamie “Ike blouses” and the Colonel will not tolerate it.’

‘One of my top sergeants had a uniform custom-made in Savile Row,’ added Colonel Dan. His voice was not entirely without a note of pride.

‘We stamped on it all pretty hard,’ said the Exec. He picked up the cardboard folder and nodded, to show that the interview was coming to an end.

‘Good luck, Captain Farebrother,’ said Colonel Dan. ‘Get yourself somewhere to sack out and make sure you report to the orderly room of the 199th Squadron sometime this afternoon. The Squadron Commander is Major Tucker—he’ll be back tomorrow.’

Captain Farebrother saluted but this time did his own, modified, version of the about-face.

It was still raining when a sergeant—his name, Tex Gill, stencilled on his fleece-lined jacket—helped Farebrother strap into one of the P-51s parked on the apron. The aircraft smelled new with its mixture of leather, paint and high-octane fuel. On its nose a brightly painted Mickey Mouse danced, and stencilled in yellow, under the cockpit, was the name of its regular pilot: Lt M. Morse.

‘Parking brake on, sir?’

‘On,’ said Farebrother. He plugged in the oxygen mask and microphone and checked the fuel and the switches.

‘Did I see you on the truck from London last night, sir?’ His voice was low and leisurely with the unmistakable tones of Texas in it.

‘That’s right, Sergeant Gill.’

‘Take it real easy, sir. These airplanes are a handful, even for someone who’s had a full night’s sleep.’

‘Is she a good one?’

‘She’s not my regular ship, sir. But she’s a dandy plane, and I’ve got to say it.’ Gill smiled. He was a big muscular man with a black square-ended moustache that drooped enough to make him look mournful. ‘Mixture off, pitch control forward,’ he prompted.

‘It’s okay, Sergeant Gill,’ said Farebrother. ‘I have a few Mustang flights in my log.’

‘You don’t want to listen to what people tell you,’ Gill said. ‘This place is no better and no worse than any other unit I’ve been with.’

Farebrother nodded. The rain continued to drizzle down from the grey stratus. Its droplets made a thousand pearls on the Plexiglass canopy. He almost changed his mind about flying up into such an overcast, but it was too late now. He grinned at Sergeant Gill, who seemed reassured by this but remained on the wing watching the whole cockpit check.

When Farebrother set the throttle a fraction forward and switched on the magnetos and battery, the instruments sprang to life. Gill used his handkerchief to wipe the rain from the windshield, and then raised the side of the canopy and thumped it home with the heel of his hand. It was a gesture of farewell. He jumped down. Farebrother looked round to be sure Gill was clear and then hit the fuel booster and starter.

There was a salvo of bangs from the engine, and the four-bladed propeller turned stiffly and halted. To the south sunlight lit the cloud. The rain was lighter now but still coming into the cockpit. He closed the side panel.

Sergeant Gill’s jacket collar was up high round his neck, but his knitted hat and fatigue trousers were dark with rain. He put his fist in the air and swung it round. Farebrother tried again. The big Merlin engine fired, stuttered, almost stopped, and then after some faltering picked up and kept going. At first not all the cylinders were firing, but one after the other they warmed up until all twelve combined to produce the ragged but unmistakable sound of a Merlin engine.

Farebrother checked the magnetos one by one before running the power up. He left it there for a moment. Sergeant Gill gave a thumbs-up and Farebrother throttled back to fifteen hundred revs and looked at his instruments once more. She seemed okay, but the Merlins were notoriously susceptible to water vapour and he let her warm up until she was very smooth.

The rain stopped and a beam of sunlight spiked through the overcast. By now there was someone on the balcony of the control tower and the men painting it had paused in their work to watch the Mustang taxi out to the runway. The engine cowling obscured his view and Farebrother steered a zigzag course along the perimeter track to make sure he didn’t let the wheels go into the muddy patches on each side. At the runway he stopped. The figure on the balcony waved an arm and Farebrother ran the engine against the brakes before letting the plane slip forward and gather speed.

She lifted easily off the ground and he brought the wheels up quickly. The cloud was lower than he’d thought; even before he was turning into a gentle circuit there were tiny streaks of grey cloud rippling across his wings.

A man has to be very young, very stupid, or very angry to do what Farebrother did that December afternoon in 1943. Perhaps he was a little of all three. First he went up to find out how low the overcast was, and then he took her on a circuit to test the controls and look over the local terrain. He treated her gently, just as he had treated the ones at Dallas every time Charlie Stigg had been able to persuade his test pilot brother that two hardworking air force instructors needed the taste of real flying once in a while.