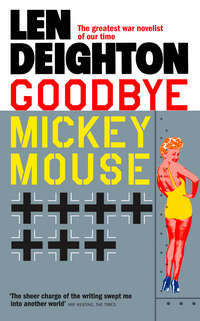

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Farebrother decided that, by luck or judgement, the unknown Lieutenant Morse had chosen a fine machine. Mickey Mouse II responded to every touch of the controls and had that extra agility the Mustang has when its main tank is more than half empty.

He pulled back the stick and eased up into the overcast. A few wisps of dirty cotton wool slid over the wings, then suddenly the cockpit was dark. The wet rain cloud swirled off the wing tips in curly vortices but the Merlin gave no cough or hesitation. It drank the wet cloud without complaint. Contented, Farebrother dropped out of the lower side of the stratus in time to see the crossed runways of Steeple Thaxted just ahead of him. He levelled off and slow-rolled to a flipper turn that gave turning force to the elevators. Then he went higher, banked steeply, and came back. This time he dived upon the field to gain speed enough for a loop. As she came up to the top of the loop, belly touching the underside of the stratus, he rolled her out and snaked away, tearing little pieces from the underside of the cloud base.

He had their attention now. Men had come out of the big black hangars, and others stood in groups on the parade ground. There was a crowd outside the mess tents and Farebrother saw their mess kits glint in the dull light as he made a low run across the field. There were people in the village streets too, and some cars had pulled off the road so the drivers could watch. Farebrother wondered whether Colonel Dan and the Exec were among the men standing in the rain outside the Operations Building.

By now he had enough confidence in the plane to move lower. He made another pass—this time so low that he had to ease her up to clear the control tower, and only just made it. The men working there threw themselves onto the wet ground, and on his next run he saw pools of spilled white paint that made big spiders on the black tarmac. He went between the hangars that time, and did a perfect eight-point roll across the field. For a finale he half-rolled to buzz the runway, holding her inverted until the engine screamed for fuel, and then split-essed in for a landing that put her down as soft as a caress.

If Farebrother was expecting a round of applause as he got out of the plane, he was disappointed. Apart from the amiable Sergeant Gill, who helped him unstrap, there was no one in sight. ‘Everything okay, sir?’ said Gill, deadpan.

‘You’d better change the plugs, Sergeant,’ said Farebrother. He noticed that Gill had put on a waterproof coat, but his face and trousers were wet with rain.

‘She’s due for a change. But I figured she’d be okay for a familiarization flight,’ Gill said in his Texan drawl.

‘You were quite right, Sergeant Gill.’

‘You can leave the chute there. I’ll get one of the boys to take it back.’

Gill walked back to the dispersal hut with Farebrother. There was a primitive kitchen there and some coffee was ready in the percolator. Without asking, Gill poured coffee for the pilot.

‘She’s a good ship, and well looked after.’

‘She’s not mine,’ said Gill. ‘I’m crew chief for Kibitzer just across the other side of the hardstand. That one belongs to a crew chief named Kruger.’

‘But he allows Lieutenant Morse to fly it once in a while?’

‘That’s about the way it is,’ said Gill without smiling.

‘Well, I hope Kruger and Lieutenant Morse won’t mind my borrowing their ship.’

‘Lieutenant Morse won’t mind—Mickey Mouse they call him—and he’s mighty rough with airplanes. He says planes are like women, they’ve got to be beaten regularly, he says.’ Gill still didn’t smile.

Farebrother offered his cigarettes, but Gill shook his head. ‘Kruger, he won’t mind too much,’ said Gill. ‘It don’t do an airplane any good to be standing around in this kind of weather unused.’ He took off his hat and looked at it carefully. ‘Colonel Dan now, that’s something else again. Last pilot who flew across the field…I mean a couple of hundred feet clear of the roofs, not your kind of daisy-cutting—Colonel Dan roasted him. He was up before the commanding general—got an official reprimand and was fined three hundred bucks. Then the Colonel sent him back to the US of A.’

‘Thanks for telling me, Sergeant.’

‘If Colonel Dan gets mad, he gets mad real quick, and you’ll find out real quick too.’ He wiped the rain from his face. ‘If you ain’t heard from him by the time you’ve unpacked, you ain’t going to hear.’

Farebrother nodded and drank his coffee.

Sergeant Gill looked Farebrother up and down before deciding to give him his opinion. ‘I don’t reckon you’ll hear a thing, sir. See, we’re real short of pilots right now, and I don’t think Colonel Dan’s gonna be sending any pilot anywhere else. Especially an officer who’s got such a good feel for a ship that needs a change of spark plugs.’ He looked at Farebrother and gave a small grin.

‘I sure hope you’re right, Sergeant Gill,’ said Farebrother. And in fact he was.

3 Staff Sergeant Harold E. Boyer

Captain Farebrother’s flying demonstration that day passed into legend. Some said that the men on duty at Steeple Thaxted exaggerated their descriptions of the flight in order to score over those who were on pass, but such attempts to belittle Farebrother’s aerobaties could only be made by those who hadn’t been present. And Farebrother’s critics were confuted by the fact that Staff Sergeant Harry Boyer said it was the greatest display of flying he’d ever seen. ‘Jesus! No plane ever made me hit the dirt before that. Not even out in the Islands before the war when some of the officers were cutting up in front of their girls.’

Harry Boyer was, by common consent, the most experienced airman on the base. He’d strapped into their rickety biplanes nervous young lieutenants who were now wearing stars in the Pentagon. And no matter what aircraft type was mentioned, Harry Boyer had painted it, sewn its fabric, and probably hitched a ride in it.

Harry Boyer not only told of ‘Farebrother’s buzz job’, as it became known, he gave a realistic impression of it that required both hands and considerable sound effects. The end of the show came when Boyer gave his fruity impression of Tex Gill drawling, ‘Everything okay, sir?’ and then, in Farebrother’s prim New England accent, ‘You’d better change the plugs, Sergeant.’

So popular was Boyer’s re-enactment of the flight that when he performed his party piece at the 1969 reunion of the 220th Fighter Group Association, a dozen men crowding round him missed the exotic dancer.

Staff Sergeant Boyer’s reputation as a mimic was, however, nothing compared to his renown as the organizer of crap games. Men came from the Bomb Group at Narrowbridge to gamble on Boyer’s dice, and on several occasions officers turned up from the 91st BG at Bassing-bourn. It was his crap game that got Boyer into trouble with the Exec.

Although Boyer and the Exec had carried on a long, bitter and byzantine struggle, the sergeant’s activities had never been seriously curtailed. But whenever it leaked out that some really big all-night game with four-figure stakes had taken place, Boyer frequently found himself mysteriously assigned to extra duties. So it was that Staff Sergeant Boyer had found himself in charge of the detail painting the control tower that day.

At the end of Farebrother’s hair-raising beat-up, Boyer looked over to the Operations Building, expecting the Exec and Colonel Dan to come rushing out of the building breathing fire. But they did not come. Nothing happened at all except that Tex Gill finally rode over to the tower on his bicycle, laying it on the ground rather than against the newly painted wall of the tower. ‘And how did you like that, Tex?’ asked Boyer. ‘On those slow rolls he was touching the grass with one wing tip while the other was in the overcast. Did you see it?’

‘He’s clipped the radio wires off the top of the tower,’ said Tex Gill.

Determined not to rise to one of Tex Gill’s gags, Boyer pretended not to have heard properly. ‘He’s what?’

‘He clipped the radio wires on that low pass.’ Tex Gill was a deadpan poker player who’d frequently taken money from the otherwise indomitable Boyer, so, still suspecting a joke, the staff sergeant would not look up at the antenna.

Tex Gill held out his fist and opened his hand to reveal a ceramic insulator and a short piece of wire attached to it. ‘Just got it off his tail.’

‘Does Colonel Dan know?’

‘Even the guy who just flew those fancy doodads don’t know. I figured that you and me could rig a new antenna right now, while your boys are finishing up the paint job.’

‘That’s strictly against regs, Tex. There’d have to be paperwork and so on.’

‘That captain just arrived,’ said Tex Gill. ‘I was with him on the truck from London last night. We don’t want to get him in bad with the Colonel even before he’s unpacked.’

Staff Sergeant Boyer rubbed his chin. Tex Gill could be a devious devil. Maybe he figured there was a good chance that the new pilot would take Kibitzer, in which case Tex would be his crew chief. ‘Well, I’m not sure, Tex.’

‘If someone reports that broken antenna, the Exec is going to come over here, Harry. And he’ll see your paintwork is only finished on the side that faces his office, and he’ll see that some clumsy lummox has spilled two four-gallon cans of white on the apron…’

Boyer looked at the flecks of spilled paint on his boots and at the insulator that Tex Gill was holding. ‘You got any white paint over there at your dispersal?’

‘I’d be able to fix you up, Harry.’ Tex Gill threw the insulator to Boyer, who caught it and winked his agreement. By the end of work that day the tower was painted and the antenna was back in position. Captain Farebrother never found out about it and neither did the Exec or Colonel Dan.

4 Lieutenant Z. M. Morse

Lieutenant Morse returned from four days in London with a thick head and a thin wallet. He desperately wanted to sleep, but he had to endure two young pilots sitting on his bed, drinking coffee and eating his candy ration and telling him all about the fantastic new flyer who’d been assigned to the squadron. ‘What the fuck do I care what he can do with a P-51?’ asked Morse. ‘I was happy enough with my P-47, and if I’d been Colonel Dan I wouldn’t have been so damned keen to re-equip us with these babies. Jesus! They stall without warning, and now they tell us the guns jam if you fire them in a tight turn.’ Morse was sprawled on his bed, his shirt rumpled and tie loose. He grabbed his pillow and punched it hard before shoving it behind his head. A large black mongrel dog asleep in the wicker armchair opened its eyes and yawned.

Morse, who’d grown so used to being called Mickey Mouse, or MM, that he’d painted the cartoon on his plane, was a small untidy twenty-four-year-old from Arizona. His dark complexion made him seem permanently suntanned even in an English winter, and his longish shiny hair, long sideburns and thin, carefully trimmed moustache caused him to be mistaken sometimes for a South American. MM was always delighted to act the role and would occasionally try his own unsteady version of the rumba on a Saturday night, given a few extra drinks and a suitable partner.

‘They say it was terrific,’ said Rube Wein, MM’s wingman. ‘They say it was the greatest show they ever saw.’

‘In your ship,’ added Earl Koenige, who usually flew as MM’s number three. ‘I sure would have liked to see it.’

‘How old are you jerks?’ said MM. ‘Come on, level with me. Did you ever get out of high school?’

‘I’m ninety-one going on ninety-two,’ said Rube Wein, Princeton University graduate in mathematics. There was only a few months’ difference in age between the three of them, but it was a well-established vanity of MM’s that he looked more mature than the others. This concern had led him to grow his moustache—which still had a long way to go before looking properly bushy.

‘I see you guys sitting there, Hershey bars stuck in your mouths, and I can’t help thinking maybe you should be riding kiddie cars, not flying fighter planes to a place where angry grown-up Krauts are trying to put lead into your tails.’

‘So who gave the new kid the keys to your car, Pop?’ said Rube Wein. This broody scholar knew how to kid MM and was prepared to taunt him in a way that Earl Koenige wouldn’t dare to.

‘Right!’ said MM angrily. ‘Why didn’t he take Cinderella or Bebop? Or better, Kibitzer, which is always making trouble. Why does he have to go popping rivets in my ship? That son-of-a-bitch Kruger is paid to look after that machine. He should never have let this new guy fly her.’

‘Why didn’t he use Tucker’s plane?’ said Rube Wein, who strongly disliked his Squadron Commander. ‘Why didn’t he take that fancy painted-up Jouster and maybe wreck it?’

‘Colonel Dan’s orders,’ explained Earl Koenige, a straw-haired farmer’s son who’d studied agriculture at Fort Valley, Georgia. ‘Colonel Dan told this guy to go out and fly a familiarization hop. Of course it’s only scuttlebutt, but they say Farebrother asked was it okay to fly it inverted.’ Meeting the blank-eyed disbelieving stares of the others, he added, ‘Maybe it’s not true but that’s what they say. The Group Exec is furious—he wanted Farebrother court-martialled.’

‘There should be a regulation about taking other people’s airplanes,’ said MM. ‘And inverted flying is strictly for screwballs.’

Earl Koenige tossed back his fair hair and said, ‘Colonel Dan said the new pilot hadn’t been in the base long enough to make himself familiar with local regulations and conditions. And the Colonel said that the especially bad weather that day created a situation in which low flying in the vicinity of the base was a necessary measure for any pilot new to the field about to attempt a landing in poor visibility.’ Earl laughed. ‘Or put it another way, Colonel Dan needs every pilot he can get his hands on.’ Having related this story, Koenige looked at MM. He always looked at his Flight Commander for approval of everything he did.

MM nodded his blessing and put another stick of gum into his mouth. It was his habit of chewing gum and smoking at the same time that made him so easy to impersonate, for he’d roll the cigarette from one side of his mouth to the other with a swing of the jaw. Anyone who wanted an easy laugh at the bar had only to do the same thing while flicking an imaginary comb back through his hair to create a recognizable caricature of MM. ‘Sure! Great!’ MM shouted, clapping his hands as if summoning hens out of the grain store. ‘And beautifully told. Now cut and print. Get out of here, will you! I’m not feeling so hot.’

Rube Wein leaned over MM where he was sprawled out on the bed and said, ‘It’s chow time, MM. How would you like me to bring you back some of those greasy sausages and those real soggy french fries that only the Limeys can make?’

‘Scram!’ shouted MM, but the effort made his head ache.

‘Rumour is that this new guy is going to get Kibitzer, and that means he’ll be flying as your number four, MM,’ said Rube Wein.

MM threw a shoe at him, but he was out of the door.

Winston, MM’s dog, looked up to see if the thrown shoe was intended for him to bring back, decided it wasn’t, growled unconvincingly, and closed his eyes again.

Not long afterwards there was a polite tap at the door, and without waiting for a response, a tall thin captain put his head into the room. ‘Lieutenant Morse?’

‘Come in, don’t just stand in the draught,’ said Morse, stubbing out his cigarette in the lid of a hair-cream bottle.

‘My name’s Farebrother, Lieutenant. I’m assigned to your flight.’

‘Kick Winston off that chair and sit down.’ MM’s first impression of the newcomer was of a shy stooped figure in an expensive non-regulation leather jacket, wearing a gold Rolex watch and with a fountain pen that was leaking through the breast pocket of his shirt to make a small blue mark over his heart. His captain’s bars had been worn long enough to become tarnished. It was a nice conceit and MM noted it with admiration.

‘I’m going to be flying Kibitzer, I understand.’

MM recognized the slight eastern accent.

‘So you’re the bastard who popped rivets in my ship.’

‘You’ve got a beautiful bird there, Lieutenant. She ticks like a Swiss watch,’ said Jamie diplomatically. MM purred like a cat with a saucer of cream. ‘But I didn’t pull enough G to pop any rivets.’

‘Where are you from, Captain?’ said MM. ‘New York? Boston? Philly?’ These rich eastern kids were all alike; they treated the rest of the nation as if they were just off a farm in Indiana.

‘I live in California, Lieutenant. But I went to school in the East.’

‘You want a drink, Captain? I’ve got scotch.’

Farebrother held up a thin hand to indicate that he wouldn’t. MM settled back in the pillows and looked at him—a poor little rich boy. Junior figured that singleseat fighters might be a way he could fight the war without rubbing shoulders with the riffraff.

Farebrother said, ‘Are we going to fight the entire war with me calling you Lieutenant and you calling me Captain?’

MM turned and held out a hand that Farebrother shook. ‘Call me Mickey Mouse like everyone else does.’

‘My friends call me Jamie.’

‘Take the weight off your legs, Jamie, and throw me a pack of butts from that carton on my footlocker.’ Morse opened a book of matches to make sure it wasn’t empty. ‘Are you fixed up with a room?’

‘I’m sleeping downstairs—sharing with Lieutenant Hart.’

‘Then you’re on your own. Hart got some kind of ulcer. He won’t be back. If you take my advice you’ll leave his name on the door and try to keep the room all to yourself, like I have this one. No sense in sharing if you can avoid it.’

‘Why are we living in these little houses?’

‘The RAF built them to house officers and their families. That narrow storeroom downstairs, where they fix sandwiches and fry stuff, used to be the family kitchen.’ Farebrother looked round the smoke-filled room. Lieutenant Morse had left no space for anyone else to move in with him. The second bed had been upended and a motorcycle engine occupied its floor space. Parts of the engine were strewn round the room; some were wrapped up in stained cloths and some were in a shallow pan of oil on the floor. In the corner there were Coca-Cola bottles piled up high on a milk crate and on the walls were pinup photos from Yank and a coloured movie poster advertising Dawn Patrol. Above the bed MM had hung a belt with a holstered Colt automatic clipped to it, and above that there was a beautiful grey Stetson.

‘And that old civilian sweeping the hall?’ said Farebrother.

‘We have British civilian servants, batmen they call them. They’ll fix up your laundry and bring you tea in the morning—well, you can make a face, but it’s better than British coffee, believe me. If you want coffee, fix it yourself.’

‘I hear you’re the ranking ace here.’

MM lit his cigarette carefully and then extinguished the match by waving it in the air. ‘You don’t have to be any Baron von Richthofen to be best around here. Most of these kids should still be in Primary Flight School learning how to do gentle turns in a biplane.’

‘Does that go for the pilots in your flight too?’

MM inhaled on his cigarette, closing his eyes as if in deep thought. ‘Rube Wein is my wingman—sad-eyed kid with jug ears, rooms downstairs. He’s no better, no worse than most as a flyer. He’s a brainy little bastard whose idea of a good time is to sit through an evening of Shakespeare, but he’s got eyes like an Indian scout and reaction times as good as any I’ve seen. And don’t let all that book learning fool you, he’s a tough little shit. When he’s on my wing I feel good.’ MM fiddled with his cigarette and tapped some ash into the tin lid. ‘You’ll probably fly wing for Earl Koenige—better pilot than Rube, he’s got that natural feeling for it, but he’s a shy kid and he just won’t get in close enough to get kills. Earl likes airplanes, that’s his trouble. He’s always frightened of bending something or damaging his engine by using full power. He flies these goddamn Mustangs like he was paying the maintenance out of his own pocket.’

Winston sighed and slid gracelessly off the wicker chair, which creaked loudly. Farebrother, who had been standing, sat down on the dog’s cushion and put his feet up on a hard chair. It gave MM a chance to admire Farebrother’s hand-tooled high boots.

‘When do you think we’ll go again?’ Farebrother asked.

‘After that Gelsenkirchen foul-up I thought we’d never go again. I had a hunch we’d all be transferred to the infantry.’

‘What happened?’

MM shook his head sadly. ‘Track in to Colonel Dan leading us to the rendezvous with the Bomb Groups at Emmerich, near the Dutch frontier. We’re tasked to give them close support all the way to the target, and then back as far as Holland again. We’re all tucked in nice and tight behind Colonel Dan. It was like an air show except that the stratus is under us and no one could see anything.’

‘Not even the bombers?’

‘What bombers?’ MM waved an arm to indicate that he could see nothing. ‘I never saw any bombers.’

‘So what happened?’

‘I’ll tell you what happened—nothing happened, that’s what happened. The bombers never found the target. The little magic black boxes that are supposed to see through cloud went on the blink, and the B-17s went miles north of our route. Cut to Colonel Dan, who’s taking us round and round Gelsenkirchen—at least he insists it’s Gelsenkirchen—but all we see is cloud. Then we fly back to England in a nice tight formation, do some low passes over the field to show what split-ass aces we are, and there’s plenty of time for drinks before dinner. Jesus, what a fuck-up!’

‘The mission didn’t bomb?’

‘Oh, they bombed. They bombed, “targets of opportunity”, which is a cute name the Air Force dreamed up for shutting your eyes, toggling the bombload, gaining height, and getting the hell out.’

‘I heard the Bomb Groups were having a tough time,’ said Farebrother. ‘I saw replacements by the truckload heading for the bombers.’

‘Slow dissolve to the Bremen mission one week later,’ said MM. ‘Seems like the target-selection guys at High Wycombe have some kind of private feud with the inhabitants of Bremen.’

Farebrother nodded politely. ‘It’s accessible; it’s near the ocean,’ he said. He reached into his shirt pocket for a packet of Camels and flicked a cigarette up with his fingernail. MM watched him light it. His hands were as steady as a rock. These rich kids are all the same—maybe it’s the school they go to on the east coast. Keep it cool, never laugh, never fart, never shout, never cry. MM admired it. ‘So what happened?’ said Farebrother.

MM realized he’d been daydreaming. He was tired and hung over—he should have told Farebrother to go away and leave him alone, but he didn’t. He told him about Bremen. He told him about the one that got torn in half.

‘We found the rearmost task force miles behind their briefed timings,’ MM said, and stopped. He’d never told the others about that midair collision, not even Rube, his closest buddy. So why tell this guy? Maybe because it was easier to tell a stranger. ‘Thank God we weren’t escorting those B-24s. They call them banana boats; they say they were flying boats that leaked so bad they put wheels on them and christened them bombers.’

Farebrother smiled, but he’d heard the joke before. He could tell that MM was stalling.

‘Those ships need a lot of babying. By the time they were above the cloud cover they were skidding all over the sky. The pilots couldn’t hold formation.’

‘It’s that Davis wing,’ said Farebrother. ‘It wasn’t designed for high loading at that altitude.’

‘Sure, something like that,’ said MM. ‘It was a bad start, flying past those banana boats, and they’ve taken so many casualties over the weeks that by now the pilots are mostly replacements who’ve never flown a tough one before.’ He flicked ash into the lid that was still resting on his chest. ‘You say Bremen’s easy because it’s on the coast, what you don’t know is that the Kraut radar chain goes right along that coast. Anything coming in over the sea comes up clear on their screens. So the fighters were waiting—hundreds of them. Did we have the shit beat out of us!’ MM found that his hands were sweating and he knew his face was flushed. ‘I drank too much last night,’ he explained.