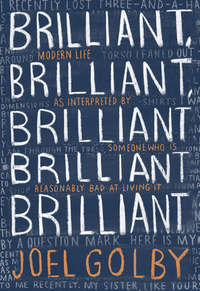

Brilliant, Brilliant, Brilliant Brilliant Brilliant

I’m on my fourth Christmas without parental guidance now, and I suppose I am okay. There are still times when I feel unutterably alone – times when all I need is my mum’s roast, or a voice that knows me on the other end of a phone to tell me things will be alright again, or what I need to do to make things alright; times when I’d give anything to go for one pint with my dad, or drive around in his smoky old Volvo listening to Fleetwood Mac. It’s weird what you miss: every holiday we had, when I was a kid, was foreshadowed on the morning of travel by my dad getting the shits – every single time, without fail – and our journey to Cleethorpes or Scarborough or Whitby or Filey would be delayed by Dad, in the bathroom, making the air sharp and sour, groaning through the door, and Mum, on her tenth or eleventh furious cigarette, hissing, ‘Every. Bloody. Time. Tony! Every. Fucking. Time.’ through her teeth, and I don’t know. Holidays don’t seem the same without this consistent element of intestinal chaos beforehand.

I picked up his camera, recently. I think a lot of people my age and of my generation get this delayed obsession with film – that gauzy, blurry, physical quality of it, haunted eyes reflected back from a flash bang, a fraction of a second of light that could have exploded – just for a moment – a day ago, or a week, a year, one hundred, more a frozen moment in time, somehow, than anything digital – and I asked my sister to dig out his old Nikon. I turn 30 this year, a moment that will be marked with me living more of my life without him than I ever did with, and it was curious, looking into that bag, reminding myself of a time left behind me: an old emergency pack of Rizlas, the gnarled old piece of tights material he used as a lens cleaner; the ephemera of a life left behind. The bag smelled of him. I held the camera up to my face, put the eye where his eye had been, nestled my nose where, years before, he would have squashed his. Click. You wonder what they would make of you, now. Click. How they might be proud of what you’ve become. Click.

Dad taught me how to make a prison bomb once. I do not think my mum ever knew about this. This was not on the family curriculum. But we were playing cards one day when I was ten, and, ‘Oh,’ Dad said, as if recalling some vital lesson all fathers teach to their children that he had somehow neglected, ‘right: you know you can make a bomb out of this?’ And I said: I’m listening.

You can make a prison bomb out of a pack of cards, Dad explained, if you cut all the little red pieces out – the hearts and the diamonds, and any red ink-like paste that might be smeared on the back – and mush them into a wet paste, which you cram down a radiator pipe or some such. When the pipe heats up – it’s an inelegant art, and results vary, so don’t, like, sleep close to it, especially not head-first – some chemical reaction will happen, which causes it to explode, dismantling the wall behind it and through which you – he motioned me in a very confident way, as if to say, ‘You, my sweet large son, are destined for prison’ – through which you escape. And that’s a prison bomb. And that’s rummy.

I didn’t really question this at the time because dad was always talking about war stuff and cannons and stuff, and also because he went to prison once. This, again, was one of those strange things that was never explained to me as being abnormal – Dad got stopped for drink-driving once and given a warning, and then he was stopped again and given a fine, and seeing as we were poor and couldn’t pay the fine he did three weeks in prison, one week maximum security and then another fortnight – after they realised how truly meek and unthreatening he was – in an open prison somewhere near Leicester. ‘How was prison, Dad?’ I asked, when he came back again. He said: ‘Not bad.’ He genuinely looked quite healthy. Prison wore well on my father.

We didn’t talk about prison much after that, mainly because it was such a pathetic stretch he did – I mean I never even had to draw a heartbreaking crayon-coloured picture of our family, labelled ‘MUMMY’, ‘DADDY?’, ‘ME’ about it – and also because Mum very strictly forbid us talking about it (she was really mad about that time he had to go to prison). But one day I answered the phone – one of my pathological childhood obsessions, for a while, was snatching the phone up and answering it in my politest sing-song – and a strange voice on the other end growled: ‘Is that Joel?’

Yes, I said.

‘Hello Joel,’ he said (imagine the voice is more prison-y than that. You are not reading it prison-y enough, and I can tell). ‘Hello, Joel,’ the prison voice said. ‘I’ve heard a lot about you. Is your dad there?’

And I said sure, who is it.

And he said, John.

And so I yelled up the stairs, D–AAAA–D, JOHN’S ON THE PHONE.

And my dad appeared before me like death had learned to shit his pants in fear.

‘Yeah,’ my Dad said, shakingly, as I watched. ‘Yeah. Yeah. Yep. No I’ll— yeah. No I’ll come to you. Yeah. Yep. See you there.’ And then he hung up and turned and swivelled into a crouch down next to me and said, Don’t Tell Your Mother.

I’m not saying who told her but she found out.

It turns out Dad had made friends, in prison, as he was wont to do as he was a very mellow and agreeable man, especially friends with his bunkmate, John, who murdered someone. ‘Yeah come over,’ Dad said into the bunk above him, confident this man would never be released from prison ever in his life. ‘We’ll get a drink. Kip on the sofa until you sort yourself out.’ And then John fucking got parole, and instantly called the only phone number he had on his person, which was my Dad’s, and asked if he could stay with us, promising not to do a murder again. The row between my parents that night – the Red Corner fighting ‘can a murderer stay on our sofa’ and the Blue Corner fighting out of ‘absolutely fucking not’ – went on so long our neighbours kept flicking their bedroom lights on and off in a really passive–aggressive way, slamming their flat fists against the shared wall that ran over our alleyway.

John never stayed, in the end – ‘Because of the murder,’ I imagine my dad saying, over the pint they eventually shared, at a pub far, far away from our house, and I like to think John was a gentlemanly murderer who waved his hand and said ‘I understand’ – but I always like that my dad even tried it: that he thought a murderer could stay with us, for anywhere between one day and six months, really says a lot about him, his gentle trusting nature and his inability to operate anywhere within the sensible laws of society.

I often imagine how I would do, in prison. Quietly, I think I’d thrive. The Boys there would at first be suspicious of my smart mouth and bookish ways, and look to teach me a violent lesson, but I think after the first two or three beatings they would take a begrudging shine to me – ‘He does reading,’ they will say, proudly, to their bunkmates, ‘He’s helping me write a letter to my lawyer’ – and that, over time, would evolve into a quiet sort of respect. One day a young upstart would try and beat me with a metal pipe on his first day to prove some sort of point, and the more seasoned inmates would jump to my defence – ‘Leave him alone!’ they’d say, ‘He’s just a harmless little soft cunt!’ – and I would say Thank You, Lads, dusting my prison uniform off, going back to my eccentric little hobby of cutting all the red bits out of cards. And then one day, just like Daddy taught me, I’d blow every one of those fuckers up to kingdom come, and sprint off into the night, hooting and hollering with delirium, until the police shot me to death with Tasers. But I still wouldn’t fucking invite a murderer to dinner, would I? Because I’m not mad.

#.

I got to tell you that there is something singularly amusing about watching a Dutch teenager swear in a flurry of American slang. Fucking shit bro, fuck man. Jord is swearing. Fucking shit man, my mom. Jord just got down to the last five of the game – 100 players whittled down to a handful over a grinding 35 minutes – and the circle draws ever tighter, pushing those last few remaining players in, and they are all concentrated on this one small patch of bushgrass, and Jord is just lining up his shot, he’ll go through the back of the head of this guy then hop over and loot his ammo then use it to take out the final two players a little over the ridge, this is a very high tension thing – and then his mum stumbles in and the mic is abruptly muted and we watch, thousands of us, in silent horror, as Jord’s entire head is shot to pieces while he pliantly talks to his mum. He turns back to the screen and sees himself as a mess of blood and ammo. Fuck man, my mom, he explains. Fuck. He rubs his eyes and regains composure. No man, she— I don’t mean that. She means well. Exit to Lobby, new game, the tide washes in with the moon.

OR: JASONR needs to piss. It is midgame – that gauzy time when the initial flurry of desperate gun-hunting and easy-pickings inner-city kills have quietened down, and so now it is a case of picking your way through the expanse, picking up improved helmets and gun sights and vehicles, taking tactical positions up on hills and the roofs of houses – and he is swimming across a small river to get to the other side of the island. But he isn’t: Jason has left his character automatically swimming – ‘I gotta pee, man’ – and everyone in the chat is deliriously tense in his absence. I seen Jason die like this, one chatter says. Another: it’s a long shot but he can take him out. Jason’s teammate, some guy a thousand miles across the country, pings to no one on the audio chat. Jason? Jase. Jase. He’s gone a really, really long time. He bobs in the water. When he returns from his piss I am once again allowed to breathe.

OR: Shroud is falling apart. ‘My eye is twitching guys, I don’t know why.’ The chat moves so fast you can hardly see it: it’s caffeine, the chat says, or you need special blue-lens glasses to play in. Shroud is hardly watching because he is focussing on just ruining the brains of the schoolyard of players who have landed around him, so his fans take it into their own hands: donations of $10 or more get read out over the screen by a robotic voice, and they use it to communicate with their god. ‘I’m not buying those blue glasses,’ he tells one donor. Another message flashes up on screen: you have a magnesium deficiency, it says. You need to buy supplements. Shroud mulls this over while he kills two guys, perfect headshots, boom. ‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘Maybe you’re right.’ He stares at the screen without blinking for five more hours. What sustains him also kills him.

OR: Shroud, again, mid-game, again, and he’s talking about his living arrangement. How he couldn’t rent this place – he gestures around him, the immaculate unfurnished flat wall behind him – because he had no credit history. But it turns out the landlord’s daughter knew who he was, how he made money, how much of it he banked, so they agreed to let the apartment to him, figuring he wouldn’t make much noise anyway. Boom, pshht, headshot out of nowhere. ‘Well, didn’t see that,’ he says, reloading the game all over again. Piss, eyes, moms, rent. Heads exploding without warning. Periodic reminders that our gods are still mortal.

#1.

I have to tell you that I am really into watching people play videogames now. I want to be clear about this: I own the means with which to play videogames myself. I have a console and a controller and a TV and games. I can, if I want to, play the videogames. But that is like saying I have a football in my garden, so why do I have to bother watching Messi. Yes, I can play videogames. I can take back the means of control. But also I am very bad at them, in a way I cannot communicate to you. I can play videogames, but it is actually far better to watch people who are good.

Twitch is a website where you watch other people play games, and I did not understand it until I got Really Into Watching Other People Play Games. The game I am obsessed with watching is Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds, which Jord and Shroud and JASONR are fantastic at, and I am appallingly bad. Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds, in short: a 100-man battle royale set across a digital island, where you parachute in and loot empty buildings until you find enough guns and lickspittle armour to mount an attack on your fellow players. The game’s active area slowly shrinks – this adds a vital layer of urgency to proceedings, to stop people camping out and games lasting eight to nine hours each – until, after about 35 minutes, the once island-sized game map is crushed into the size of a single field, and it becomes a kill-or-be-killed hellscape. The first time I played it I died within one minute and proclaimed the game to be ‘bad’ or ‘shit’ (I forget which). Second time I made it until about three minutes in, before I was cleanly dispatched by an uzi for an overall ranking of around #89. My friend Max then took over, and came #2 overall, after a 40-minute stand-off, a Jeep chase, an exquisite sniper takeout and this one time where he threw a grenade into a room. The final battle saw him and one other fight for supremacy around the edge of a hill, and he was taken out by a single bullet to the side of the head. Here is an impression of me, sat on a computer chair at Max’s shoulder, trying not to breathe too loudly and so put him off his aim: ‘[Hands held over mouth, breath held, voice coming out strangled and high pitched] Fuck! Shit shit shit! Fuck!’ It was the most exhilarating gaming moment I had ever seen. I mean, Christ man. I live a relatively empty life. It was possibly the most exhilarating anything moment I had ever seen. So you see now how instantly I was hooked.

But as we have discussed I am terrible at the game (my simple mind cannot, however way I try, get my head around the W–A–S–D keyboard movement system, and for now PUBG is PC-only), so instead I watch Jord play it on Twitch. Or: I watch Shroud on Twitch, because his American time zone means it’s easier to watch in the evenings (at weekends, when I want to wake up and watch someone playing videogames who isn’t me, I watch American streamers who stay up deliberately late in their time zone to catch the European early morning audience, and they all wear caps and have obnoxious catchphrases, and I universally hate all of them). I watch some guy called JASONR sometimes, and though I don’t like him as a human, I respect him as a player: all three of them have this preternatural reaction time, a kind of hardwired cold-bloodedness and resistance to panic, unerring accuracy with digital rifles even over long distances, and also this relentlessness: they wear their rare losses lightly, so when their heads explode in the middle of a grey-brown field they, instead of wail and gnash with the sting of loss, boot up the game and go again. Essentially: the mindset of highly tuned professional athletes, but in the bodies of slightly awkward nerd teens. Twitch is a curious beast: a YouTube-shaped streaming platform that technically can be used to broadcast anything but is almost exclusively used for showing people playing games, Twitch was bought for $970 million by Amazon in August 2014 and is now worth an estimated $20 billion, with its own sub-currency tipping system – the ‘Cheer’ – slushing around its network. Fans of streamers can pay $1.40 to buy 100 ‘Cheers’ which they then donate to their favourite gamers through various in-chat messages (the gamer themselves will get around $1 for every 100 cheers – Twitch needs to take its vig) and emoticons: for a sneak peek at the future of capitalism, there is a single emoji that costs $140 to enact. Alternatively, fans can donate directly to streamers – tipping the odd $5, $10 here and there, or subscribing for a fee every month, thank you bro, thanks for the sub, thank you guys for the donnoe – with more money going directly to the gamer’s coffers. So to reiterate: Twitch is a website where you can watch someone else play a game and, if you really want to, you can pay the person you are watching to let them let you watch them play a game. At no point in this interaction do you, personally, get to purchase and play the game. You only watch. Some Twitch streamers are multi-millionaires. It has previously been impossible to tap into why.

#2.

I know why, and I and I alone have figured out why. In the adolescence years 13 thru 17 – a four-year long feeling of emptiness and antsiness and crushing, overpowering horniness I am going to nominally refer to as Wanke’s Inferno – I would go to my friend Matt’s house and watch him play videogames. It wouldn’t matter what time I would go over there – 2 p.m., 10 p.m., 2 a.m. – Matt would be awake, and playing videogames. This is because Matt was a goth, and goths are always up playing videogames. Also his mum was a nurse who worked nightshifts so his house was always best to scratch at the window if an existential crisis hit at 1 a.m. and you just needed to be out of your house and in the vague presence of some company, which very often happens when your body is pulsating with the dual needs to i. grow, constantly, in every direction and ii. be so horny your head might explode. Everything seems happy and sad at the same time when you are a teen. Psychically it’s like putting your head in a washing machine, for eight years.

Here’s what the back of Matt’s head looks like: an at-home dye job is growing out, so at the crown of his head is a digestive biscuit-sized circle of his natural hair colour, somewhere between blond and brown, while the rest of his hair was dyed black (see: goth) with a stripe at the front that was electric blue (also see: goth). The stripe didn’t last long, actually – it is hard to maintain an electric blue stripe of hair at the best of times because it requires bleaching the hair and then dyeing over the top of that bleached hair in the colour of your choice, and bright colours wash out quickly, and being a goth on pocket money is the exact polar opposite of the best of times, so after a while the blue fell out and there was just a sort of pale blonde streak remaining. I remember all of this vividly because for an entire summer of my teens I looked fixatedly at the back of Matt’s big goth head while he played Quake 4, Unreal Tournament, and, for some reason, this extended six-week period where we linked a SNES up to an old CRT TV and compulsively played Dr. Mario until the sun came up through the trees.

I mention all this because going to a friend’s house and watching them play videogames is exceptionally nourishing to teen boys. I mention all this because all those half-conversations I would have with the back of Matt’s head while he coldly racked up headshots were some of the best and also least consequential of my life. I would lay on his black bedsheets (goth), play with a skull candle of his (goth), flap at the blackout curtains (goth goth goth), occasionally disassemble an old Warhammer model of his (nerd) or read a comic (nerd) by Jhonen Vasquez (goth), and Matt would still be that, spine curled, hand on the mouse, headshot after headshot, while I unloaded. It was as close to therapy as two teen boys can get: chatting, and chatting, and chatting, every worry and every gripe, every girl we liked and every hope for the future, who we wanted to be, what we feared, how scared we were to grow up: all without a scrap of eye contact, conversation occasionally just falling into a lull, of grunts and occasional laughs, as heads exploded and arms came off in geysers of blood. Occasionally I would fall asleep on a Sonic beanbag on his floor, and have to be wearily stirred awake again at 4, 5 a.m., when I would wander home in my shirtsleeves through the chill. As I grow older, I am more deeply aware than ever that, essentially, a very large part of me has always wanted to retreat back into the nerve-jangling terror womb of adolescence, whether in search of a hard reset, or a time when life was consequence free, or just to be 17 again and actually learn to drive this time. I feel most men, given the option to go back and revisit their teen years with an adult mind, would for some reason jump at the chance. It was a time when your body is lithe and willowy and full of potential, and way less hairy. The most exciting thing that can happen to you is you can distantly see a girl you are in love with – and who is unaware you are alive – at the mall. It is a horrible, terrifying, high adrenaline time to be alive and I miss it with every atom of my body. Watching my friends play videogames emulates that feeling of distorted comfort all over again. Doing so with some Dutch guy called Jord over Twitch allows me to wallow in a black bedsheeted pit of nostalgia from the comfort of my desk at work.

#3.

Twitch taps into a new media landscape that makes absolutely no sense to fucking anyone, but that seems to be the way things are going, and Twitch is only one strange facet of that. Example: I recently had lunch with a friend and he told me about his obsession with Dr. Sandra Lee, or ‘Dr. Pimple Popper’, a woman with an immaculate bedside manner and a preternatural gift for lancing cysts, who lives both in her doctor’s office and also on YouTube. Every video she has ever done goes like this: a floating, eerie mid-zoom of the boil or zit or massive tumour-esque mass she is about to explode, which she prods at with rubber-coated fingers, purring and describing it in a cheerfully clinical tone. Then: then a jump-cut to the boil or whatever swabbed in surgical cloth. And then, using either her fingers or precise metal tools, she slices it open and squeezes out all the yellow gunk inside. It is horrible and fascinating: watching poison ooze out of humans, thick custardy torrents of it, then stitched neatly up and dabbed over with surgical spirit. My friend, a neat freak with OCD, says it taps into his compulsive need for things to be clean, tidied, free of chaos. ‘I watch them while I’m eating my breakfast,’ he says, the maniac. ‘Muesli, yoghurt, zits.’

OR: I found myself in a cab recently having one of those conversations you only seem to have when you’re shouting from one end of the car to another, and in it I was explaining the concept of ASMR. ASMR, or ‘autonomous sensory meridian response’, is this tingling effect some people get in their ears when they hear certain sounds – paper crinkling, soft finger clicking, whispering – something close to synaesthesia. YouTube has thousands of hours of videos dedicated to ASMR triggers, and a small-but-dedicated audience hungry for more, but obviously it’s very hard to just whisper for 30 minutes straight, so you find these performances quickly veer into something very weird – they are all recorded at 4am, when outside static noise is at its lowest, and the performers all do these weird drama class ad-libs, talking to themselves through various whispered scenarios. So like: one guy does this bit where he is an extremely rude waiter, talking down to you about a reservation you didn’t make uninterrupted for 40 fucking minutes. Or: there is this one guy, Toni Bomboni, who looks sort of like a LazyTown villain come to life, and I once watched a video of him in the scenario of ‘a gum store’, where he would chew and taste various bubblegums on your behalf to help advise a very serious gum purchase you (the viewer) were going to make, again something that went on, whispered, for like three-quarters of an hour. So I mean go to TV and say, ‘Hey: I’ve got a half-hour video of a lad chewing gum to himself and urgently whispering. You uh … you want that?’ and TV will say: no thank you. But the Internet has carved out its own weird niche of anti-media. Some people just like watching people do mad and boring shit. Some people like to watch skin erupt, or maniacs whispering. I, for example, I can only relax to headshots.