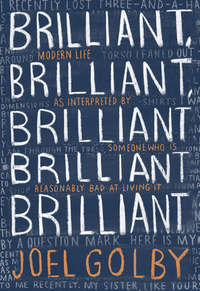

Brilliant, Brilliant, Brilliant Brilliant Brilliant

#4.

As best I can tell there are four or five species of Twitchers (I do not know if ‘Twitchers’ is a word or the accepted term: we are just going to have to assume that it is), which can be categorised as thus:

— Extremely Hyperactive Kid Who You Just Know Got Put Bodily Into Some Lockers At School: these are of course my least favourite Twitchers, because they are boys who fundamentally did not fit in to the intended hierarchy of the world of school or work – they were down at the bottom, punching fodder for jocks and so on, not smart enough to be genuine nerds, not physically dextrous enough to fight anyone off, doomed forever to be henpecked and unhappy – but then who found their niche (streaming videogames to an audience of millions) and so jumped up through their expected social stratas and became as obnoxious as possible in as short a period of time, so they have adopted the sort of bro-y discourse of actual bros, and say things like ‘fam’ and ‘you guys’ and ‘wuh–POW!’ and ‘[every single irritating sound effect a human being can make with their mouth]’, and gurn to the camera, and develop their own little catchphrases and routines, and behind them is a plethora of sort of wide-tyre nerd culture ephemera – anime posters, figurines from popular adult cartoons, Monster-branded green neon-lit mini-fridges, extremely complicated gaming chair/gaming headset set-up – and then they act in front of it, and they are extremely annoying, these people, on the surface, but also very much you can see not even very deep within them to see the vulnerabilities and frailties within, and I just know that every single one of them I could make cry with an accurately timed ‘your momma’ joke, and that’s no way to respect another adult, is it—

— Quiet PhD Student Type Who Just Loves Exploding Digital Heads: these ones are my favourite, because they transcend the idea of performative streaming – i.e. the idea that streaming videogames is about anything other than the videogame and the skill they possess at the videogame – that being a personality is secondary, tertiary, to having quick mouse response times and unerring accuracy with a sniper rifle, and these are the guys who take it closest to a sport. There is a narrative, in sport, of showboaters and not: the lads who have hot new hairstyles, and tattoos, and take selfies on Instagram, and still ascend to the very top of the game (in football: Neymar, Beckham, C. Ronaldo), and they infuriate your dad because of it, and then you have those who don’t, head-down-and-score-a-lot-of-goals lads (again football: Messi, Shearer, Xavi), who your dad adores. That’s the split in sports: that being good at sport – at being one of the five very best people on the planet at kicking a football – but also having ego around that, at being happy to be nearly supernaturally good at something, is somehow profane. In sports, I love these showboaters: when it comes to watching them play shoot-em-ups, they tire me out. Give me a quiet Dutch lad who is killing 40 minutes before he does his homework any day of the week.

— ‘The Character’. Some streamers dress in wigs and wraparound shades and eighties-style leather jackets and the like and maintain all these catchphrases and go-to sayings and stuff like that and in one way I very much admire them for developing a character and sticking to it, unbreakably, like a mid-eighties American shock jock, and in another far deeper way I cannot watch even one minute of them playing videogames, holy jesus, I am never in a thousand timelines going to be wired-out on Red Bull enough to find that funny—

— Girl Streamers, who unfortunately have this horribly uphill battle to Prove Themselves To Be Sincere, the gamer boys who are so primed to watch girls in like calf-high socks and pigtails and full-face anime-inspired make-up kill dudes in battle royale settings and do kawaii peace signs to the camera being sort of bait as well as red rags to these dudes, dudes both wanting very much to sexually conquer them – the chat that runs alongside Girl Gamers being, essentially, pornographically explicit – as well as mad at them for liking their safe little male thing, intruding into their world, so Girl Gamers are seen as a sort of strange curiosity in a male-dominated sport (even for male-dominated sports e-sports is a male-dominated sports), but also I find the associated energy that goes after them fundamentally fatiguing, so I cannot watch them for very long, and that is my cross to bear, sorry ladies—

#5, OR: THE AUDIENCE WILL EAT ITSELF EVENTUALLY

Like religion, the audience makes this something bigger than it is. Without a flock, preachers shout to an empty room, and Twitch is similar: streamers have a symbiotic relationship with their audience, they shape them and are shaped by them, a constant feedback loop with a clear hierarchy, gods and believers. The geography of the classic Twitch screen goes a little like this: down to the left-hand bottom of the screen, you have a fixed three-quarter view of your chosen gamers face, blank with concentration: to the right, a chatbox trickles constantly along. In the middle of the screen, prime real estate, is where the bulk of the gaming action happens, and occasionally our mighty overseers will flick their eyes over to the chat – ‘What we saying, chat? Where’s that sniper at?’ – but mostly they are fixed on their jobs, which is to explode people’s digital heads. And so there is this sub-economy of attention that goes on: for subscribing to their favourite gamer, fans’ names are briefly displayed on-screen, where they often earn a shout-out; by donating five or ten bucks, they can have a message displayed in the middle of the heads-up display, right where their hero is aiming, as close as they can get to god. So here’s where you get these weird little one-sided conversations, as followers yell praise to on high: ‘Thanks Shroud, you’re the best!’ they say. Or: ‘Hey Shroud: what hair product do you use?’ (They want to be him the same way kids want to be Ronaldo, the way men want to smell like David Beckham.) You see how weird humanity can get when left alone for too long in the same room. ‘Hey Shroud,’ one donor says. ‘Noticed your submachine gun shooting rhythm matches the drumbeat to an intro on my favourite anime.’ This person is insane. ‘That deliberate? :)’ Or: you gain insight into who is watching, and where, and why: ‘Hey man,’ one donor writes. ‘Stationed in Afghanistan right now and missing my games. Watching you keeps me going. Rock on.’ In many ways, Twitch is a long-distance friendship simulator, the humming sound of male bonding. A big ding, an animation, a series of catchphrases and in-jokes, long developed with a community that is at once guarded and open: someone has donated $3,100. The gamer reels back in his chair. ‘Wow,’ he says, barely flickering with emotion. ‘Hey man, wow. Thank you.’ Without the audience, the Twitch streamer is nothing, and they run the gamut from fanatical to removed, but always, there, there is this bubbling economy: in a world where artists struggle to sell honest-to-goodness CDs, and where movies are torrents and books are downloaded, Twitch streamers just sit there and shoot, their own little sub-niche of entertainment, and their fans are breathless to hand them money for it.

#6.

And so obviously, I pay to watch a man shoot. I’ve been watching Shroud for weeks, the grace of his movements, the way no ounce of motion is wasted, as slick and refined a professional gamer as it is possible to be. I watch highlight reels when he’s not online and find myself re-watching explicit kills on my lunch break. One day, I see Shroud, midway through a seven-hour stream, do the most audacious move: he throws a grenade from about 200 yards away then runs into the building just as it tinkles to the ground and explodes, slipping through a concrete bunker window and violently wounding the two players inside, who he finishes off with a single one-two pelt from his shotgun. I literally go into work the next day and describe all this to the IT guys as if we were talking about a football game. There is something hypnotic, about it, something soothing – something that takes me back to the womb of adolescence, sitting in a room silent but for the occasional jagged explosion sound, the pierce shrill of digital screaming, a punching noise run through two cheap portable speakers – takes me back to 15, staring at the back of a head, rapt with it. Twitch, on the surface, very much doesn’t make sense – the entire model of it seems wholly unsustainable, like selling one-way tickets into the heart of the sun – and that maybe in five years, or ten, gamers will have to drop their handles, go by their real names, slink into the corporate world of work. Or maybe it’s something else: a weird cusp of a mega-economy, one that will create celebrities and gods for generations to come. All I know is, I sign up to connect my Twitch account to my PayPal account. And that I wait for the right time when Shroud is looking at the screen (a lull between two games, when, after a top-three finish that ends with an outta-nowhere sniper kill, he clicks back to the lobby to reflexively find another game). And then I push the button on donating $10. ‘Hey Shroud,’ I say. ‘Thanks for the headshots.’ And he turns to the screen and reads my name aloud. And I feel like I have been touched by god.

Show me a boy who didn’t once between the ages of 13 and 21 try and suck his own dick and I will show you a liar. My method, which I was convinced was the one to finally crack this case, was to lie on my back lengthways against my bed and, raising my back and my legs against it, slowly push my lower half against the solidity of the bed frame, slowly folding myself in half like a dick-sucking sandwich or falafel wrap. I mean obviously this did not work. All it really did was left a perfectly straight purple bruise perpendicular to my spine that didn’t go away for weeks. But I think I tapped into something, there, in the grey-dark of my bedroom at night, desperately trying to press my dick down into my mouth: I unlocked a certain spirit of adventure, the same one that pulsated through more heroic men before me, the ones that unlocked pyramids and discovered America. The same yearning to push myself to the very limits to see if I could suck myself off is, in many ways, the same urge that first sent man to the moon.

In secondary school my friends and I passed the same tattered biography of Marilyn Manson around between us, because we were all similarly obsessed with the curious black-and-white streak of a man shocking America top-to-bottom at the time. This was around the time Manson released his mainstream-puncturing Tainted Love, which feature him in an electric-blue hot tub – one eye milky and blind, long wan body, jet black bob, arms longer and more slender than any non-horror movie human deserves to be, winding those limbs and hooking them beneath the shoulders of the hottest video girl ever committed to film, a girl who was all kohl eyes and double-Ds and who stuck her pink tongue out luridly when Manson touched her, possibly the coolest and most erotic image I had ever seen, then, and probably still have to date – and we longed both to be him and know all about him. And, too, Manson was the recipient of a rumour that passes like a torch down from generation to generation of schoolkids who just discovered cumming for the first time: that he, surgically and at great expense and cost, had four of his ribs removed so he could better suck his own dick.

A part of me misses the innocent version of myself that could believe this rumour. (Prince, purportedly, did the same thing; Cher supposedly had hers removed to have a smaller waist; if you are a lithe pop star, just know that schoolchildren are going to speculate about the length of your ribcage.) Now I know more about human sexuality and the sheer allure of rock stars and/or anyone famous and creative, I know the truth of the matter was: Marilyn Manson didn’t need to suck his own dick because he had so many people willing to suck his dick for him. Sucking your own dick, conversely, is seen as some great feat of sexual braggadocio, when actually it should be seen as similar to being one of those IT nerds who upgrades his usual handjob technique to work in a Pocket Pussy®: ‘I have given up on convincing another human being to touch my junk,’ the Pocket Pussy® owner is saying, ‘the touch of this rubber fuck toy is the only joy I will ever know.’ A cursory glance at the search string ‘do you have to remove your ribs to suck your own dick’ paints a bleak, stark truth of the rumour. ‘Manson did not get that done,’ reddit user zaikanekochan says plainly. ‘Grow a bigger dick.’

I was at university the last time I tried it – my method this time was to bob my head down towards my crotch at great pace, like a sudden cobra strike, hoping to catch my body off-guard and accelerate straight from head to dick – but sadly, obviously, it didn’t work. I had another realisation, there, stripped to my pants in the grey light of my bedroom, neck cricked down towards my crotch: talk to some girls, maybe, go outside, stop expecting flexibility to somehow secretly develop within you, maybe convince someone else to take this job on. Ribs are there to protect your heart and lungs, obviously, but they also act as a sort of built-in rev limiter: without them, mankind would become a dick-sucking ouroboros, dick to mouth and mouth to dick, and we wouldn’t talk to women, or procreate, or do anything, really. If I could suck my own dick I wouldn’t be writing this, right now, because I’d be too busy sucking my own dick. In the Bible, Adam gave his rib up to create Eve, and there weren’t any explicit passages about her sucking dick but you have to assume it happened at some point. That’s the sacrifice, there: God showed us the way before we even knew it. And, I suppose, this is what I’ve learned about myself: that I’m glad I’m not Marilyn Manson, ribless and pale in the smoked-out back of a 1999-era tour bus. That I’m glad I have so many ribs. And hey: I guess this is growing up.

In no particular order:

I.

Bridges. This one is justified: when I was an early teen I had a sit-bolt-upright-with-the-cold-sweat-dripping-off-you nightmare where – on an old grey concrete bridge that connects Chesterfield town centre proper to the train station nearby, one that runs over an A-road and so is extremely fun to spit over – I was walking along the bridge, in a dream, and then for whatever reason and in a perfect one-two-three motion I put one foot on the kerb of the concrete, grabbed the railing with both hands, jumped off the edge of it and exploded on the road like a melon. In the dream the remaining pulp of me got run over by a truck, one final indignity, and I don’t think it’s unrelated that ever since then I have been very cautious on bridges. This isn’t so bad: I just try my best to walk as close to the exact centre of it as possible, so whatever kamikaze autopilot that spins like a top inside of me at all times doesn’t tilt over and override all sense and logic and I just leap forever off the bridge, to death, but it does make me wary. If you can’t trust yourself, who can you trust? Who can you trust? But yeah: the main takeaway of that nightmare 17 years ago is I’m really very irritating to go for a nice meander along a canal with.

II.

Speaking of nightmares: for some reason the greatest and most frightening nightmare I ever had was when I was five years old and the blood-red velvet curtains that were in my bedroom (apparently I grew up in a fucking haunted Victorian mansion owned by an eccentric doctor and not, like, a normal terrace in a red-brick street in the Midlands?), so yeah the blood-red velvet curtains formed in their wrinkles a face, enormous and frowning, and in a deep voice the velvet face shouted at me for not tidying my room enough and for generally being a Bad Boy. I think it says a lot about my formative neuroticism that the main nightmare I had as a child was not a Frankenstein monster or some vampires but my own curtains telling me off for being naughty, but the result was the same, and that result was: I pissed the bed in fear and woke up screaming. This necessitated a particularly high-stress intervention by my father who had to unhook two heavy velvet curtains from the rings about my bed at 3 a.m. while shouting and surrounded by the ammonia-like smell of fresh piss, plus all the sheets needed changing, and though I’m not saying I’m scared of curtains exactly, I would say I am very careful around them, because I know now what they are capable of.

III.

Dogs. Listen: I am fully aware that dogs are fundamentally perfect wholesome little animals, essentially human hearts full of love and made dog-sized – just pure heart-meat, dogs, right to the core – and that being afraid of them is ultimately absurd when their primary function is to love and adore. I get this. However, when I was a small meek child at my mother’s knee on a rare trip back to London to see the old friends she had left behind there a decade before and introduce them to the grown child that had ruined her life in such a way that she had to leave them to raise it, I was taken to a large grand house where all the adults drank wine and smoked and laughed very loudly, which when you’re a small meek child is a high-stress situation anyway, because all you really have is a box of orange juice and you’re in the kind of adult house where they have absolutely no prearrangement for children (‘Oh you want … something to. Do. Okay: would you like to read this encyclopaedia?’). When I was there, amongst the smoke and the adult cackling, their medium-sized Rottweiler jumped towards me and barked, and I instantly realised that dogs aren’t hearts with fur on at all, they are pure prime muscles constantly ready and prepared to jump up vertically and bite you on the dick, and my instinctive reaction to this was to sob – obviously, I thought, the dog was going to gnaw my dick off in one smooth primal bite, and I would have to live a life without it, a sort of modern eunuch, and they would call me Dog Dick Boy – and then everyone had to stop drinking wine and smoking and instead calm the hysterical child down, and in the cab home there was definitely A Silence between my abruptly sober mother and I, and it was pretty clear that me being suddenly afraid of dogs had entirely ruined the evening, and I’m not sure our relationship ever truly recovered from that, really, and I have been cautiously wary of dogs ever since. Cute, yes, but very capable of biting you on the dick.

IV.

Maybe I just have a fear of losing my dick in some sort of dick accident, actually.

V.

Sudden rushes of fear were an oddly common phenomenon of my childhood. As a kid I deeply loved escalators, almost to the point of mania: every time we encountered an escalator, in a store or mall, I would demand to ride it up then down, then beg to go up then down again, a lone passenger on the world’s lamest rollercoaster. Then, one time at the big M&S in the centre of town, I sprinted towards the escalator filled with glee that quickly turned to horror: watching as my mother went up the machine ahead of me, I realised suddenly escalators were just stairs made of monstrous metal teeth, ferrying you unrelentingly towards the top of them, where you would be crushed and gnawed to death by the spiked outer workings of the machine, at which point I stopped abruptly, foot hovering over the killer belt beneath me, and started both yelling and crying at the same time, a little like this noise: ‘HUAAAAAAAAAH.’ I kept sort of yell-crying while my mother floated up away from me, bent backward screaming ‘WHAT?’ and ‘WHAT IS WRONG?’, until a kindly woman lifted me up above her head and carried me, gurgling and shouting and crying in one perfect triptych howl, to the top of the stairs, and the rest of the shopping trip passed otherwise without incident. Again: I’m not now afraid of escalators exactly, but I am very cautious.

VI.

(Other things I loved deeply as a child to the bafflement of everyone around me: hub caps, the protective-cum-decorative plastic shields on the wheel rims of cars, which I developed an encyclopaedic knowledge of when I was a kid because I liked cars but couldn’t see from my short height any particular part of them other than the wheels, an obsession that led to a point where I would collect discarded hub caps we would come across in the street and I was able to identify vehicle make and models only by their hub caps. Sample conversation from my childhood: ‘Hey Dad! Dad! This Volvo has newer hub caps than the one on our street!’ and my dad would say, wearily: ‘Yes’.) (I have since almost entirely gone off hub caps. They leave me cold.)

VII.

The way other people handle and prepare raw chicken. No judgement – I’m not exactly briefed on the correct code of hygiene around chicken myself – but quite often if I am watching amateur cooking shows I see people do things with raw chicken that strike me as ludicrous or insane, like using a wooden chopping board or rinsing it haphazardly under a tap, and it’s made me constantly on guard about how any chicken I have eaten has made itself to me. A useful question I like to ask before any meal I eat: has anything happened in the preparation of this food that might cause me, violently, to shit myself? It’s not a healthy way to live but it’s the way I choose to.

VIII.

I do fear wardrobes falling onto me and the subsequent coffin-like encasement in them and the obvious analogue for death that comes attached to it, after that time a wardrobe fell on me as a kid and it felt like my end had come. I remember feeling like I had died, but also very much feeling quite calm about that, but it’s made me afraid of precariously balanced wardrobes since, and I think that’s fair: I suppose we are, all of us, constantly shaped and smoothed by the fears we accrue as we age. A lot of our fears are completely justifiable, and as a result we hold them close around us, like rosaries.

IX.

One very specific fear I have is that a number of television personalities who I have spent a lot of my time detesting because of small perceived micro-aggressions against me – the guy from the GoCompare adverts, for example, or Jamie Oliver – are actually incredibly sound in real life and I would get on with them really well, and an ongoing fear fantasy is that I meet Jamie Oliver one day and he’s really nice to me – ‘Cor,’ he says, with that big tongue of his, ‘yeah you’re really sound – let me get you a pint!’ – and not only do I have to sit through the drink with him but I also have to admit, privately, to my biggest critic (myself) that I was wrong all along, and that Jamie Oliver is sound as fuck. I think that’s me projecting a fear, actually: I’m not afraid of Jamie Oliver being sound, am I? That’s simply impossible. I am afraid of being fundamentally, deeply wrong. I am afraid of the embarrassment that comes with backing down on an opinion I have that is only important to me.

X.

At the time of writing (Oct., 2k17) I am in the midst of a break-up, and while largely that is good, I suppose one enduring fear is the main one that comes with break-ups, i.e. the fear not that a person you shared tender words and embarrassing little nicknames and fragile plans for the future with now keeps texting you to call you a ‘dick’ or ‘dickhead’, but that the break-up – the final, actual act of breaking the bond of the relationship you are in – has now actually severed and deleted various alternative timeline futures for you, and the one you are left in is the one where you never know happiness again. So for example: one alt-universe timeline that has shot off into the infinite void was the one where you were happy and became married and had two perfect little cherub-faced children, and you spent your weekends barbecuing and doing maths homework with a toddler that looked like you both. Or: so for example the future where you both grew old and gnarled and knew each other perfectly because you had over the years hewn gaps out of each other that only the other could fit in, one bulbous old ying and one haggard old yang, so that in this (now deleted, forever) future you could communicate with each other without even words, just with gentle looks and hand touches and knowing nods, and you would die together, ancient hand in ancient hand, watching the gauzy sun set beyond you, rocking back and forth gently in armchairs on a porch. The fact is that there are now a hundred thousand timelines gone – holidays you had, drinks you enjoyed, expensive meals and cheap ones too, Christmases you will no longer have, birthdays that go uncelebrated, dogs and cats that lived entire wholesome lives within your joint care – because you basically had one argument over Netflix that got a bit out of hand. It is just you, now, alone as alone can be, that all future companionship has been deleted forever, from this point in your life onwards – so yes going off-piste a little but that prospect seems like a low-hum kind of constant soaring fear—