The Duffer’s Guide to Painting Watercolour Landscapes

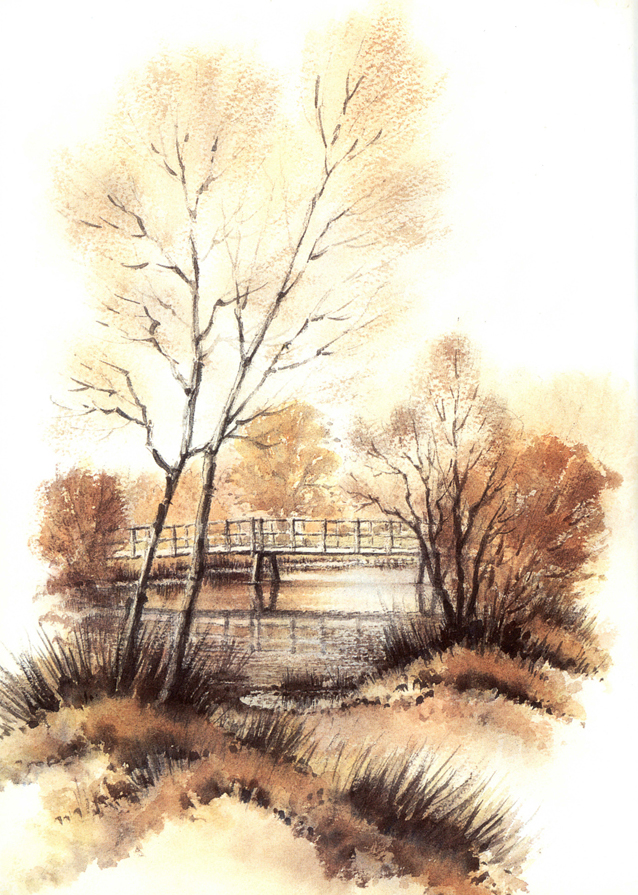

LAKE AT MOORS VALLEY 56 × 37 cm (22 × 14½ in)

Copyright

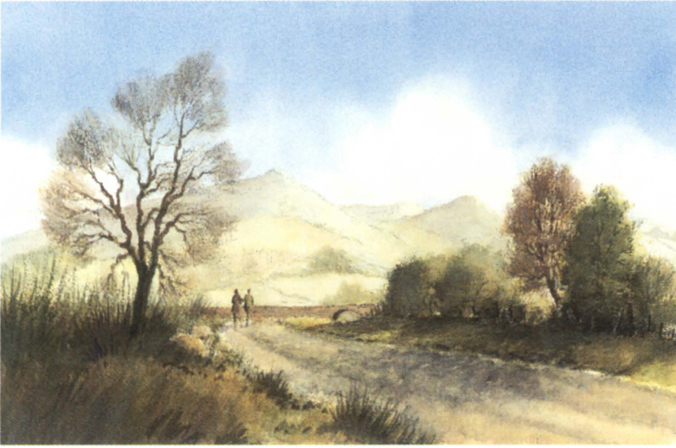

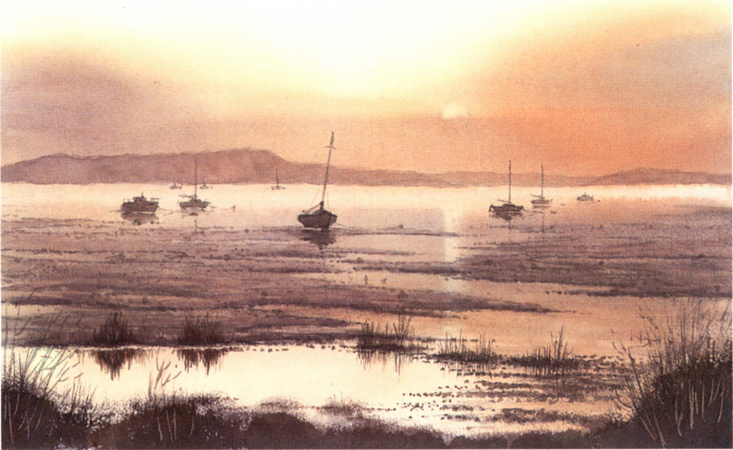

VIEW FROM SHINAFOOT 33 × 51 cm (13 × 20 in)

First published in 2000 by

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is: www.harpercollins.co.uk

Collins is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers Limited.

© Don Harrison, 2000

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Editor: Geraldine Christy

Designer: Colin Brown

Photographer: Nigel Cheffers-Heard

A companion video, entitled The Complete Duffer’s Guide to Painting Watercolour Landscapes, is available from Artyfacts, P. O. Box 2182, Poole, Dorset BH16 6YU

Page 1: EILEAN DONAN 35 × 53 cm (14 × 21 in)

Don Harrison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN 9780004133997

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2019 ISBN: 9780008352431

Version: 2019-03-06

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT

USING COLOUR

FIRST STEPS IN WATERCOLOUR

SIMPLE SKIES

WINTER LANDSCAPES

SUMMER LANDSCAPES

SEASCAPES AND BOATS

MOUNTAINS AND HEADLANDS

BUILDINGS IN THE LANDSCAPE

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

MUDEFORD 37 × 56 cm (14½ × 22 in)

Introduction

Even in this day and age we can still be overwhelmed at the sight of a stunning view. Indeed you may often hear people say, ‘Just look at that. If only I could paint it.’ So why on earth do they not do so? Many people say they have no talent for painting or they cannot draw, or the scene is too difficult, or they will take up painting when they retire. Sadly, they are missing out on one of life’s great pleasures. Even worse, a large proportion of the people who already try to paint often struggle through poor technique and lack of good advice. Some regard themselves as complete duffers and wonder if they will ever improve. This book is intended to change all that and to show just how easy it is to paint effective and realistic landscapes in watercolour.

Here is a basic, but comprehensive, painting course arranged and written in a straightforward, no-nonsense way that is easy to understand. If you have always longed to paint but do not know where to start, here are the answers. The book introduces the materials and equipment you will need and provides a guide to basic colour theory, with advice on laying out your palette and mixing your colours. Techniques are clearly explained, followed by simple exercises to help you put them into practice. Finally, each chapter culminates in a full step-by-step demonstration of a painting.

MORNING SNOW

38 × 56 cm (15 × 22 in)

The heavy overcast sky provides just the right backdrop to the distant snow-covered fields and is painted using the same cold blues and violets that are used for the snow-bound lane and fields. These wintry colours contrast well with the rich, warm browns in the hedges and trees.

HARVEST TIME

37 × 56 cm (14½ × 22 in)

The light fluffy clouds in a blue sky suggest a warm summer’s day and the bright, warm yellows and greens, framed by the dark overhanging foliage, emphasize this feeling. The tractor provides a touch of action and a useful focal point in the painting.

After reading this book you should be able to tackle almost any kind of scene with confidence. But if some of your early efforts are unsuccessful do not worry – remember that you are only spoiling a piece of paper. Even your reject pictures should teach you something useful for future paintings as long as you understand where you went wrong.

When you first start painting the temptation is to reproduce exactly what you see, but the camera can do this much better than you or I. So once you have chosen a subject, try to simplify it and produce a reasonable impression of it without including every detail. When your painting does come out right you will realize what you have been missing all these years.

Your days as a ‘duffer’ are numbered!

MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT

Like most hobbies, painting requires an initial outlay in materials and equipment. It is all too easy to be misled into making a poor choice and many beginners buy huge amounts of materials and equipment when only a few basic items are really needed to get started. In the long run, it pays to use really good-quality materials and ensure that you have the right tools for the job. Then all you need is to learn how to use them to the best advantage – I hope this book will take care of that.

As far as paints are concerned, you will probably read a lot of conflicting advice about how many colours you should have. Most professional artists have their own particular favourites, but make your selection based on common sense and your own preferences. Paper is very much a personal choice and it is worth experimenting to find the surface that suits you best.

STONEHAVEN HARBOUR

38 × 56 cm (15 × 22 in)

This busy harbour was packed with boats, so I simplified the scene, including just enough detail to make it interesting. You can make full use of your range of brushes when painting a complex scene like this.

Paints

Paints are normally sold in tubes or as flat pans. I suggest you avoid pans because it is more difficult to load the brush properly, especially when the pan is hard. Even when pans are soft and moist they still do not offer the flexibility of tubes, which allow you to squeeze out the amount of paint you want when you need it. Most people start off with the old paintbox they used at school with horrid little hard pans of paint and dreadful cheap brushes. If you try using a large brush to pull out a single colour from these pans it is difficult to avoid picking up the colours on either side. There is very little space to mix colours, so the chances are that you will put lots of water into one of the wells and finish up mixing watery colours. Do yourself a favour and throw your old paintbox away.

If you can, buy the best artists’ colours you can afford. They are a pleasure to paint with and give you stronger, more vital colours that will impart more zing to your paintings. Students’ quality may be less expensive, but the colours are often insipid and the pigments lack strength, so you may use more paint in the long run.

I recommend using artists’ tube colours. My preferred starter selection would be Cadmium Red, Alizarin Crimson, Cadmium Yellow, Lemon Yellow, Cobalt Blue, French Ultramarine, Raw Sienna, Burnt Sienna and Burnt Umber.

Palette

My preferred option is a circular plastic palette, offering ample space for mixing and room to fit the colours round the edge. If you arrange them in a set position, it is a simple matter to locate the colours easily without having to think where they are each time. You can use alternatives to this type of palette – for example, an enamel plate or a plastic butcher’s tray. But the important point is to have a large mixing area.

Place generous amounts of your colours evenly spaced around the edge of the palette, leaving a large mixing area in the centre.

Brushes

Duffers often seem to be over-equipped in this area as they are easily swayed by marketing claims of special properties for gimmicky brushes. Experience will prove that you only need a few brushes if you learn how to use them properly. My own collection includes the following brushes.

Hake – 50 mm (2 in). Buy a stitched variety with plenty of body. Good-quality hake brushes do not splay out because the goat hairs bend inwards at the ends, making it easy to form a ‘chisel’ edge. Avoid hakes with metal ferrules – these are more suited to stippling or cleaning your water buckets.

Flat brushes – 25 mm (1 in). Use a smaller one if you find this size hard to handle. A synthetic brush is quite acceptable, but check before you buy that the bristles will form a neat chisel edge without separating when damp.

Medium round brushes. A size 5 or 6 and an 8 are useful for finer work. It pays to buy quality here – Kolinsky sable by choice, as these hold their shape and form a good point for finer work. They should be ‘springy’ when dry.

Large round sable. A size 14 is ideal for large washes. Mine has a blunt end because I do not use this for delicate shapes, so it is unnecessary to have one with a point.

Long-haired size 1 rigger. This is perfect for fine detail and is more controllable than a small round brush for fine work.

Filbert hog brush. Usually associated with oil painting, a bristle brush is ideal for lifting out colour or using with dry paint for foliage or hedgerows.

Goat-hair mop or Squirrel brush (optional). Useful for sky washes and clouds.

These are the brushes that I find most useful for painting watercolour landscapes.

1. Hake 2. 1 in flat brush 3. Round No.5 4. Round No.8 5. Large round sable 6. Long-haired size 1 rigger 7. Filbert hog brush 8. Goat-hair mop 9. Squirrel brushWatercolour paper

Beginners often start with pads or blocks. However, pads are only suitable for sketching as the loose flapping edges make it impossible to keep the paper flat – clipping the sheets together at the corners can help. Most pads and blocks consist of sheets of thin paper, with the result that when you damp the top sheet you also damp the one below. Then they both tend to cockle and it is hard to control the moisture and the paint.

Unless it is stretched, thin paper cockles when water is applied liberally. Instead, use single sheets of good quality 100 per cent rag paper – 400 gsm (200 lb) or thicker. Try out different makes to find the best surface for you. Choose paper with a slightly rough surface, either Not (Cold Pressed) or Rough. Avoid Hot Pressed, which is too smooth. Heavy paper is expensive, but at least you can use both sides. Keep odd pieces of the same paper you use for painting for testing paint consistency and mixtures and for wiping surplus paint or water from your brush.

Other useful items

As well as paper, paints and brushes there are several other items that you will need in the course of painting.

Pencils

Hard, thin-leaded pencils tempt you to draw rigid straight lines and work in a fussy, detailed way. Soft-leaded pencils, ranging from 2B to 7B, will encourage the use of ragged strokes and a looser approach to your work. Avoid holding the pencil like a writing pen, with a rigid forefinger. Hold it higher up and use flowing strokes. Instead of straight lines, move the pencil point up and down a little as you move it to create a jagged line. Leave a few gaps in the line here and there – the viewer will fill them in visually. Think like an artist, not an engraver.

Erasers

Use erasers sparingly to avoid damaging the paper surface – a soft putty eraser is best. Leave the rough pencil outlines on the paper when you are painting, unless they are very heavy.

Sketch pads

Carry a sketch pad around to make quick drawings of any interesting subjects you come across. For colour reference sketches use watercolour pads or small loose sheets. Cartridge paper is fine for sketching, but useless for painting on as it has a poor surface.

Easels

A metal easel is light in weight but stable enough for working on location. I work with the board fairly upright, which discourages the use of excess water. You should be able to tilt the board to a horizontal position when required to control the movement of wet paint. Painting boxes also provide a useful easel. A low-cost alternative is to use wooden blocks to slope the backing board.

A painting box incorporates a lift-up easel. It can also be used to store your painting equipment.

Backing board and clips

It is essential to keep the paper flat while working, so attach it to a backing board cut slightly larger than your selected paper size. Thin plywood or blockboard is ideal. Use spring clips to retain the paper at each corner. This method also allows you to pull the paper flat if it bulges a little after damping. Do not stick masking tape all round the edge of the paper or it will ridge up like a corrugated roof when water is liberally applied to the surface.

Water pots

Always use two plastic water pots or jars – one for rinsing your brush and one for clean water for mixing – or you will never paint fresh-looking paintings. Make sure the top opening is large enough to take your largest brush. Position the pots below the level of your painting to avoid splashing your work.

Don Harrison in his studio. He uses both a lightweight metal easel and a painting box, which allows him to be flexible in his working approach.

Kitchen roll

Use absorbent kitchen roll rather than tissue, which can leave a fluffy residue on your paper.

Palette knife

Widely used by oil painters, a palette knife is an excellent tool for lifting out paint to suggest light stems or trunks of trees. It can also be used flat to the paper for moving paint around to create a textured effects on rocks.

Masking fluid

Masking fluid, or Frisket, is useful for masking off small white areas. Apply it with a damp or soapy brush to make the bristles easier to clean. Only remove the masking when the paper is fully dry.

USING COLOUR

Used in the right way, colours can create visual excitement or a mood of peaceful tranquillity. They can be garish and strident or restful and harmonious, bold and powerful or incredibly subtle. Colours can make or mar a painting, so they are a crucial part of picture making. But for the new painter, choosing the right colours and understanding how to mix them can be a minefield.

The plethora of books, videos and magazine articles simply adds to the confusion, offering an overwhelming amount of conflicting advice. Some suggest a limited palette, while others promote the use of many hues.

Most people require a simple-to-understand, easy-to-remember system for selecting, mixing and adjusting colours. This chapter provides a logical explanation for choosing particular colours, with some simple mixing techniques to help you arrive at the hue you want quickly and easily.

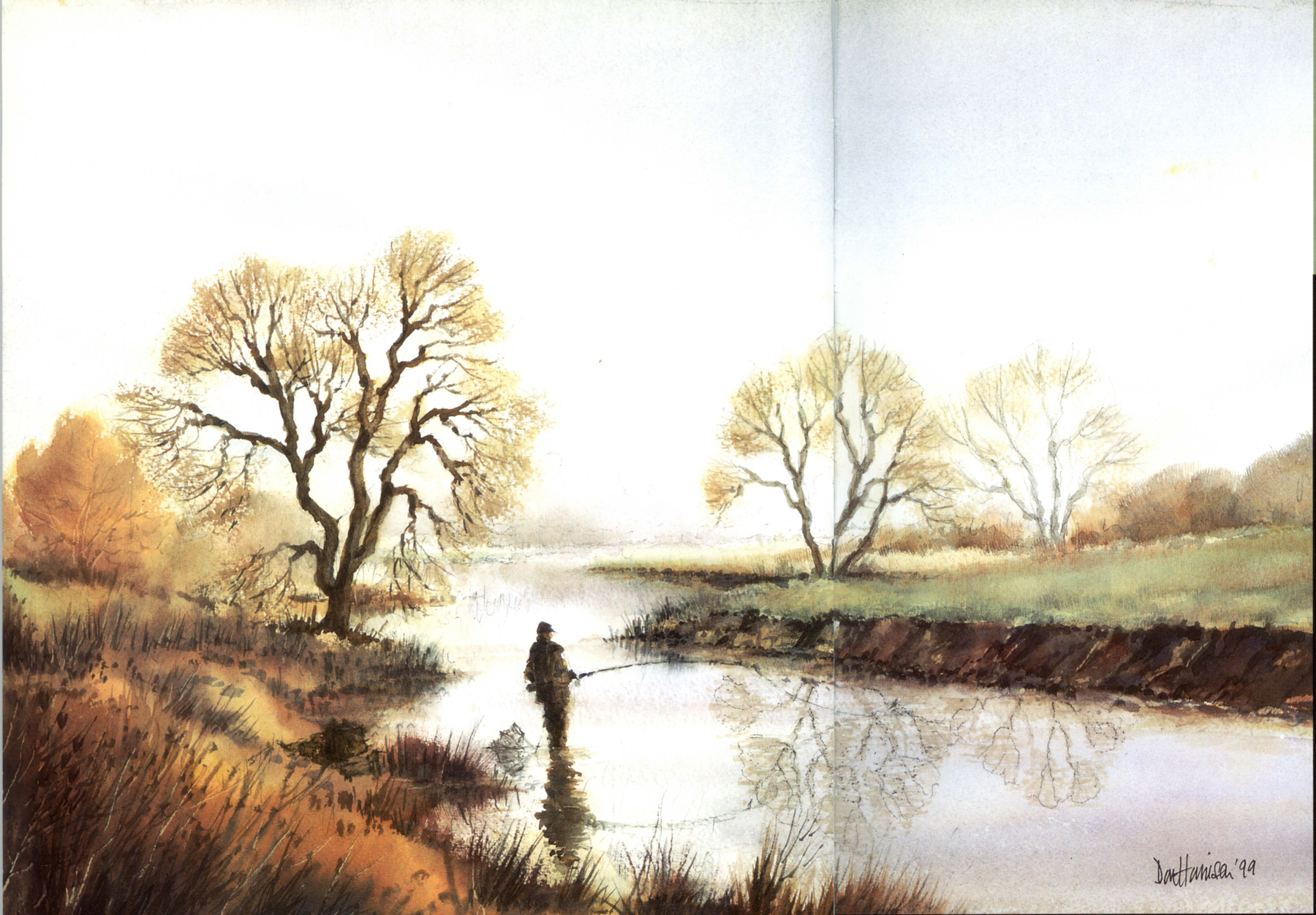

FISHERMAN AT PARLEY

38 × 56 cm (15 × 22 in)

The autumn trees have shed much of their foliage, but the colours are essentially warm. The pale neutral sky and the cool colours of the distant trees contrast well with the warmer colours in the foreground.

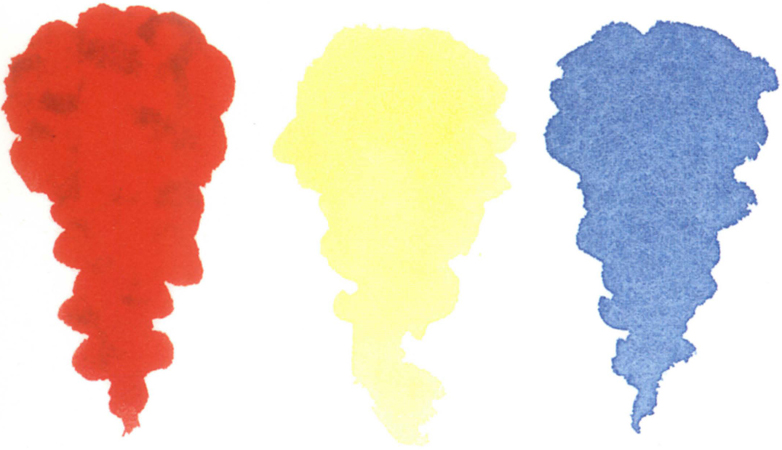

Primary colours

As children, we are taught about colour in simple terms. We are shown how the colours of the rainbow can be formed into a circle to make a colour wheel and told how the primary colours red, yellow and blue cannot be mixed from any other colours. For artists, this basic thoeretical knowledge can help the colour mixing process. Use the order of the colours in the colour wheel as a handy guide for arranging the paints on your palette.

Primary colours – reds, yellows and blues – are so called because they cannot be mixed from other colours. They form the basis for all colour mixing.

Complementary colours

Most of us know what happens when different primary colours are mixed together – red and yellow make orange, blue and yellow give green and red and blue produce violet. By adding the second primary in each case, a secondary colour mix is produced. Logically, if these secondary colours can be mixed from the primaries, there is no need to buy them for your palette.

Each secondary colour, having been mixed from two of the primary colours, is usually referred to as the complementary colour of the other primary. Thus the complementary colour of red is green (a mixture of the other two primaries), the complementary colour of yellow is violet and the complementary colour of blue is orange. So what, I hear you ask? The useful point to remember is that placing complementary colours next to each other makes each of them stand out vividly. On the other hand, mixing all three primary colours together in roughly equal amounts results in dark grey or muddy colours and should be avoided.

Even when you know how to mix these combinations of primary colours, you may still find it difficult to make a particular hue. You would be right in thinking that a few more colours might be useful. But what colours should you choose and in any case why select particular primaries instead of alternative reds, blues or yellows, and what difference will choosing different ones make? Read on!

The standard colour wheel, showing six colours. These are the three primaries – red, yellow and blue – and the three secondary mixes – orange, green and violet.

Warm and cool colours

When we look at colours they have an obvious warm or cool appearance. In fact, we tend to think of violet/blue/green colours as cool and red/orange/yellow colours as warm. This warm or cool look can be used to create a mood or seasonal influence.

If your selected colours include a cool and a warm version of each primary this gives you the flexibility to mix almost any colour you wish. Manufacturers have different names for similar colours, so choose them visually. For example, Lemon Yellow and Aureolin have the greenish yellow appearance of real lemons whereas Cadmium Yellow Deep and Gamboge will both lean towards orange and look like strong custard. Do not buy ready-mixed greens, oranges or violets – these can be mixed from the primaries.

THE VALLEY

34 × 57 cm (13½ × 22½ in)

The warm colours of the foreground grasses and mountains on the right are in stark contrast to the cool blue/green slopes of the other mountains in shadow. Using a juxtaposition of warm and cool colours is an effective way of giving the impression of depth.

Laying out the palette

You may prefer different primaries to the ones I use, but make sure you include warm and cool versions of each and judge their suitability for yourself by eye. My usual primaries are Cadmium Yellow (warm) and Lemon Yellow (cool), Cadmium Red (warm) and Alizarin Crimson (cool), French Ultramarine (warm) and Cobalt Blue (cool). Useful additional colours are Raw Sienna, Burnt Sienna and Burnt Umber. These nine colours are sufficient to get you started and you can add to them later if you wish.

If you place your colours on the palette to roughly match the colour wheel, you can find them easily without having to think. I like to arrange the three pairs of warm and cool primaries first, leaving a good thumb’s width between each primary and leaving an equal gap around the perimeter between the pairs. Squeeze out generous helpings of paint– if you use a tiny squirt it will be difficult to load the brush properly.