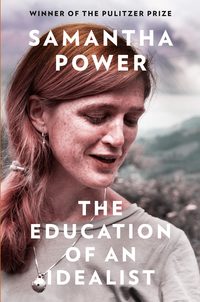

The Education of an Idealist

What I did not know then was how consequential my refusal to take no for an answer—and Marty’s decision to take a chance on me—would prove for my life’s trajectory.

UPSTANDERS

I had heard the saying “You don’t read a book; a book reads you,” but the truth of these words did not sink in until I traveled the country and began meeting people who had read “A Problem from Hell.”

Many had marked it up with yellow highlighters or plastered it with Post-it Notes for quick access to the parts they found most important. Activists told me they were reading the book to think through how they could better influence Washington decision-makers on a host of different issues. Synagogue congregations grappled with the book’s invocation of the false promise of “never again.”

People who hadn’t followed the Rwandan genocide when it happened said to me, with great earnestness, “I should have at least called my congressman.” The book had quoted Colorado congresswoman Pat Schroeder describing the reaction to the Rwandan genocide in her district. “There are some groups terribly concerned about the gorillas,” she had said in 1994, noting that a Colorado research organization studied Rwanda’s endangered gorillas. “But—it sounds terrible—people just don’t know what can be done about the people.” The paucity of domestic political awareness and pressure were key reasons even low-cost US policies went untried.

The reaction I least anticipated came from those who had no connection to the specific countries I wrote about, but who were drawn to questions about the nature of individual responsibility in the face of injustice. I found that readers from all walks of life identified with the quests of Lemkin, Proxmire, Galbraith, and the officials who resigned from the State Department. College professors assigned excerpts in broad survey courses on leadership and ethics. I received numerous emails and letters from people who said that these stories had inspired them to see how to be more active in social causes.

Somewhere along the way, I began describing the book’s protagonists—those who tried to prevent or otherwise “stand up” against genocide—as “upstanders,” contrasting them with bystanders. I noted that very few of us were likely to find ourselves the victims or perpetrators of genocide. But every day, almost all of us find ourselves weighing whether we can or should do something to help others. We decide, on issues large and small, whether we will be bystanders or upstanders.

Thanks initially to teachers who began to use the idea of upstanders to engage their students, the term started to catch on. Many years later, when I was UN ambassador, I was stunned—and profoundly gratified—to be informed by a reporter that the Oxford English Dictionary had added the term upstander, which it wrote was “coined in 2002 by the Irish-American diplomat Samantha Power.” Of course, it proved far easier to coin the term than to know exactly how to be an upstander in my own life.

Beyond the grassroots interest that developed around the book’s themes, real-world events expanded its audience. I was editing the page proofs six months before publication when al-Qaeda terrorists murdered nearly 3,000 Americans on September 11th, 2001. These attacks, and the political reorientation they caused, changed the entire context in which most Americans thought about US foreign policy. The sense of isolation from global threats that the United States had enjoyed for so long had been shattered, and people began to discuss America’s responsibilities around the world in new ways.

The devastation of September 11th was followed by an intensifying domestic debate over whether the United States should go to war with Iraq. Although the crux of President George W. Bush’s argument for removing Saddam Hussein from power was the national security threat posed by his alleged weapons of mass destruction, Bush and others in his administration often seized upon the fact that Saddam had “gassed his own people” as proof of the Iraqi regime’s dangerous tendencies.

Articles assessing the merits of an invasion in the New York Times and The New Yorker cited “A Problem from Hell” in their descriptions of the Iraqi campaign of genocide against the Kurds. I was uncomfortable seeing my writing about atrocities used in a way that might help justify a war. In my interviews, I tried to remind people what I had actually written.

I had made several arguments. First, I noted that when crafting foreign policy, US officials naturally think through the possible economic and security consequences of their choices, but they needed to do far more to factor the human consequences into their deliberations as well.

Second, I emphasized that the United States has a large toolbox when it comes to preventing genocide. I described the many options short of military engagement at the disposal of a powerful country like the United States: public and private diplomacy, public shaming, negotiations, deploying intelligence and technical resources, international peacekeeping, arms embargoes, asset freezes, and more. Although I sometimes heard people describe the book as an extended argument for US military action in response to mass atrocities, I had actually written that the United States “should not frame its policy options in terms of doing nothing or unilaterally sending in the Marines.”

As the New York Times noted a month before the invasion of Iraq, “Ms. Power bridles at critics who interpret the book as a simplistic call for military intervention in cases of humanitarian crises. Her point, she said, is not that the United States failed to intervene in Cambodia, Iraq or Rwanda, but that it failed to do anything at all.”

While Saddam was a merciless dictator, I did not see that as sufficient reason to go to war. I believed that neither the Kurds nor the American people faced an imminent threat of the kind that justified the use of force. Some of our closest allies opposed the war, and I was also concerned about the repercussions of going it alone. These countries would hardly be eager to help rebuild Iraq in the aftermath of a US invasion.

Although I abhorred the prospect of Saddam remaining in power, I ended up speaking out against the Iraq War on a number of occasions. As I told Newsweek in early March of 2003, roughly two weeks before the war began, “[The invasion] will ratify and fuel the bubbling resentment against the U.S., and this anti-Americanism is the sea in which terrorists thrive.”

Yet the coincidence of publishing the book in relative proximity to the start of the war made “A Problem from Hell” liable to misinterpretation. A year after the war began, I again registered my frustration in an interview with the Financial Times, remarking, “The book is the furthest thing from a plea for American military intervention … [or] for unilateral military intervention on a whim or on a subjective set of excuses and justifications.” To this day, however, I am still approached by people who ask how I could have supported the Iraq War.

A MONTH AFTER THE US INVASION, my publisher called and informed me that “A Problem from Hell” had won the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction.

“Are you sure?” I said, my knees buckling beneath me.

I left a message for Mum to call me back and managed to reach Eddie. My voice caught as I said softly, “I just won the Pulitzer Prize.” Eddie had fostered my love of history. He had read and edited easily a dozen drafts of the lengthy book. After its publication, he had traipsed across New York City each week, stopping at various Barnes & Noble stores to move copies from the less visible history section to the displays at the front of the store, hustling to his next location whenever he was caught by a store clerk.

“What?” he said. When I repeated my news, he said, “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph.” Then, clearly in a state of shock, he asked, “For what?”

“What the hell do you think?” I asked, laughing. He told me to call the publisher back: “They need to get the Pulitzer sticker on the paperback!” he exclaimed.

When Mum called from the hospital a few minutes later, I paused before picking up, just to prolong the moment. When I told her the news, she said, “Ahhh, isn’t that just marvelous, Sam. Marvelous. And to think, you were having such a hard time with that bloody article …”

I had talked to her the previous night about my struggles with a magazine piece I was writing. For my mother, a major perk of winning the Pulitzer was that it would cheer me up. But I later learned that she was so excited about the news that she told all of the hospital nurses she worked with, as well as her favorite patients.

IN TRUTH, I FELT a profound disconnect between my personal good fortune and the state of the world. Around the time the American occupation of Iraq began spiraling out of control, the Western media started reporting about mass atrocities in a place called Darfur.

Most notably, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof traveled to the Chad-Sudan border, writing ten impassioned columns in less than a year to draw attention to the massacres being perpetrated by the Arab-led Sudanese government against African ethnic groups. The more I read of Kristof’s reporting, the more I suspected that the Sudanese military and affiliated militia were perpetrating genocide. The Sudanese government, led by Omar al-Bashir, seemed intent not only on crushing a nascent rebellion in Darfur, but also on destroying the lives of many Africans there. I felt compelled to investigate what was happening.

Articles about the atrocities in Sudan frequently quoted a former US official named John Prendergast. John had previously served as an Africa adviser to President Clinton, and was now working as an analyst with the International Crisis Group, the nongovernmental organization that Mort had helped create back in 1995 (and that I had briefly worked for during law school). Although the organization generally tailored its recommendations for policymakers, John seemed more focused on convincing Americans at the grassroots level to pressure their elected officials to take action to stop atrocities. He argued, just as I had in my book, that because genocide was rarely seen to implicate “traditional” national security interests, citizens would need to make political noise if they wanted Washington to do more.

When I finally had the chance to hear John speak at an event in New York, I approached him after the Q&A and asked if he would be willing to give me a tutorial on Sudan. He had first visited the country in 1987 and had traveled there on many occasions, often for months at a time. After establishing that we were both lovers of baseball, we agreed to meet up in May of 2004 for a Kansas City Royals–Boston Red Sox game. Our outing ended up launching what would be one of the most important professional collaborations—and friendships—of my life.

As we sat side by side along Fenway’s third base line, we talked about how our desire to fit in as kids had helped spark our love of baseball. We also discussed the role that tenacity—and serendipity—had played in our respective careers. The son of a frozen-food salesman, John is a six-foot-one former high school basketball player with a perennially unshaven look and shoulder-length hair that began turning silver in his twenties. He moved around a lot as a child and attended five colleges before graduating from Temple University. In 1984, when he saw television footage showing the famine in Ethiopia, he decided to make his way to Africa. Traveling around the continent, John began writing reports for UNICEF and Human Rights Watch on government and militia abuses against civilians.

Over the years, as he documented crimes that powerful perpetrators didn’t want exposed, John was taken hostage in the Congo, survived mortar fire in Somalia, and was imprisoned in Sudan. But he was upbeat when he talked about Africa and its potential. He predicted that we were entering a period in which Americans—especially young people on college campuses—would rise up to demand a different kind of foreign policy from Washington. “It’s all about pressure,” he said. “Governments will do the right thing, or less of the wrong thing, if people make clear that they care.”

We also plunged right into talking about our personal lives, each of us quickly sizing up the other as incurably single. John had a magnetic personality, and I had been advised that women flocked to him. He told me he had ended a short-lived marriage and was now dating several women at once. My most lasting relationship was still with Schu in college, and I saw nothing on the horizon likely to change that. We didn’t verbalize that day what we later realized we had decided: this was a friendship that was going to last forever. We were not going to endanger it with a romance neither of us could sustain.

We did, however, almost immediately begin brainstorming about how we might collaborate. I floated the idea of traveling to Darfur together, telling him about the “X test.”

“If the most we’re able to do is bear witness and use what we see to activate more Americans to care,” I said, “it will be worth it, right?”

John did not need convincing. By the time the final out of the game was recorded, we had decided on a date for the trip.

THE EASIEST WAY TO REACH DARFUR was not via the Sudanese capital of Khartoum, but by crossing the border from neighboring Chad. John and I traveled there during the summer of 2004 and spoke with dozens of Darfuri refugees about the horrors they had endured. The woman who made the deepest impression was Amina Abaker Mohammed, a twenty-six-year-old Muslim mother of six who was a member of one of the three ethnic groups being targeted by the Sudanese government. As John and I sat cross-legged in the sand under the shade of a tree, Amina stoically recounted what she had experienced. What she said defied belief.

Amina lived in a Darfuri farming village near a town called Furawiyah. The previous year, she had begun to hear that the Sudanese government and nomadic Arab bandits known as janjaweed[fn1] had begun attacking non-Arab ethnic groups, including hers.

Amina reported that, six months before, a Sudanese military aircraft had fired four rockets near her home. Although one rocket failed to explode, she said, the others left large craters in the ground. She and her husband refused to abandon their land, but they dispatched five of their six children to the nearby mountains for shelter. Amina’s oldest child, ten-year-old Mohammed Haroun, remained with her to help take care of the family’s precious livestock.

Shortly after dawn on January 31st, 2004, Amina said, she and Mohammed arrived at the wells to draw water for their animals. They heard the sound of approaching planes, and fifteen minutes later, Sudanese aircraft began bombing the area. She and her son were separated. Amina saw Sudanese soldiers come tumbling out of trucks and Land Cruisers, followed by hundreds of menacing janjaweed on camels and horses. Most of the janjaweed wore turbans around their heads and mouths so that only their eyes were visible. In the initial onslaught, she saw dozens of her neighbors and hundreds of animals killed.

Amina scrambled with several donkeys to a red-rock hillock 300 yards away. Though she thought Mohammed had escaped, when she looked behind her, she saw that he had remained at the wells to try to wrangle the family’s panicked sheep. As a circle of several hundred janjaweed tightened around her son, Amina ducked behind the hillock to pray.

By nightfall, the sounds of gunfire and screaming faded, and Amina returned to the spot where she had last seen Mohammed. She found a grisly scene. Rummaging frantically around the wells by moonlight, she saw the dismembered bodies of dozens of people she knew, but was unable to find her firstborn.

Suddenly, she spotted his face—but only his face. Mohammed had been beheaded. “I wanted to find the rest of his body,” she told me. But she was afraid of the janjaweed, who remained nearby, celebrating their conquest with a roast of stolen livestock. She carried what she found of her son to the mountain where her other children were hiding. “I took my child’s head, and I buried him,” she told John and me, dabbing her tears with the tail of her headscarf. A week later, Amina and her five remaining children made the seven-day trek to Chad, where we would meet them.

Although we had only recently become acquainted, John and I hardly had to discuss our next move. We hired a Darfuri driver to take us across the Chad-Sudan border to Furawiyah, where we would do our best to confirm what Amina had told us and assemble proof of the Sudanese government’s crimes.

Advancing at less than ten miles per hour, we drove in 130-degree heat through the inhospitable terrain of western Sudan, where virtually all human life seemed to have been forced into exile or hiding. We felt utterly alone.

As we drove deeper into Darfur toward Amina’s hometown, we passed through the village of Hangala, where we found the charred remains of huts that had been set ablaze. Each had been reduced to stone walls and mounds of ashes. Amid the debris, we came across the remnants of a jewelry box, a bicycle, and women’s slippers. Of the 480 people who lived in Hangala before the attack, we were later told, 46 were murdered. The rest were now homeless, scattered throughout Sudan and Chad.

In the ransacked village next to Hangala, we found a child’s backpack and his “Duckzilla” notebooks, which contained exercises in mathematics, Islamic studies, and Arabic. In another house, we found small packages of beans and nuts, a sign that the inhabitants had fled in a hurry. As we left one hut, where pots had been overturned and valuables looted, we spotted three toothbrushes tucked into the thatch in the roof. Nestled next to them was a sheet of paper that had been folded into a tight square. Upon opening it, we found a few lines of handwritten Arabic script. Our translator told us that it was a prayer from the Koran, urging Allah to keep watch over the family home.

When we finally reached Furawiyah, we asked to be directed to the wells. As a local resident steered us, we passed a large gray rocket that was partly lodged in the sand; this was the undetonated Sudanese Air Force ordnance that Amina had described. We also passed an enormous crater, at least twenty-five feet in diameter and five feet deep, where another bomb had exploded.

“Here are the wells,” our guide said as we pulled up to the area that Amina had depicted on a map she had drawn for us. I saw only more Sahara sand.

“What wells?” I asked.

The guide kept pointing to the same patch of desert, and, frustrated, we stepped closer. There, barely visible beneath the pale-yellow sand, were the faint outlines of the rims of one large stone well and two smaller ones. This was where Amina and her son had watered their animals, and where Amina had later found Mohammed’s severed head.

The janjaweed had stuffed the wells with bodies and buried their victims beneath mounds of sand. In so doing, they had destroyed water sources vital for the survival of people in the area. Among the twenty-five wells around Furawiyah, we learned, only three still functioned—and those would surely dry up soon due to overuse.

The young man who showed us the wells then took us on a short drive outside Furawiyah to the base of a slope. We climbed out of our Land Cruiser and started to ascend on foot. The stench of decomposing flesh hit us before the rotting bodies, in gullies on either side of the hill, finally came into view.

Fourteen men, in bloodied traditional white djellabas or in shirts and slacks, were lying dead in the sand. I counted seventeen bullet casings scattered around them. It looked as though the men had been divided into two groups and lined up in front of the ditches. They had all been shot from behind, except for one man. His body lay not in a ditch, but in the center of the slope. One of his palms was outstretched, as if he had been pleading for mercy.

WHEN JOHN AND I RETURNED to the United States, we publicized what we had learned as widely as possible. He wrote an op-ed in the New York Times, and several weeks later, I contributed a long article to The New Yorker called “Dying in Darfur,” which opened with Amina’s story. Together, we also did a TV segment that aired on 60 Minutes. We each had full-time jobs—I was still teaching at the Kennedy School, and John was writing reports for the International Crisis Group on a broad range of African conflicts. But we joined others in trying to pressure the Bush administration to take meaningful action to do more for the people of Darfur.

Thanks in part to John’s relentless activism, which brought him to college campuses, churches, and synagogues around the country, an unusual coalition of students and religious groups began to coalesce. The US Holocaust Memorial Museum strived to be a “living memorial” that would use the history of the Holocaust to educate—and motivate—future generations. The museum had already hosted me, John, Nick Kristof, and other speakers to talk about Darfur. In July, it officially issued a “genocide emergency” warning on Darfur, the first time it had ever made this designation. The same month, the museum and the American Jewish World Service teamed up to establish a broad network of faith-based, advocacy, and human rights organizations, which eventually included 190 groups and operated under the banner of “Save Darfur.”

John and I donated the children’s schoolbooks and backpack, the toothbrushes, and the crumpled prayer to the Holocaust museum. We were not sure the people who owned these items were still alive, and, if they were, we assumed they would not be returning to their razed homes anytime soon. The museum staff turned our photos and artifacts into a gripping exhibit, which generated additional public interest.

Evangelical Christians had a history of protesting mass atrocities in southern Sudan (which was home to a substantial Christian population), and now they began raising money for Muslim survivors in Darfur. In August of 2004, thirty-five evangelical leaders, representing fifty-one denominations and 45,000 churches, called for “swift action” from President Bush to “prevent further slaughter and death.” When I reached out to a prominent evangelical leader to better understand what was driving the community, I received a refreshingly straightforward response. “Killing is wrong, whether you’re killing a Jew, a Christian, or a Muslim,” he said. “God made the people there in Darfur. For us to ignore them would be a sin.”

Private citizens and students across the country threw themselves into the Darfur campaign. A piano teacher in Salt Lake City donated two weeks’ of her earnings. The pastor of a Methodist church in Ohio asked congregants to spend half as much on Christmas presents as they usually did, and to contribute the rest—raising $327,000 for relief efforts. At Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, a group of students heard reports that a tiny African Union monitoring mission in Darfur didn’t have the budget to afford flak jackets. They raised $300,000 to help equip the beleaguered African Union personnel. Other college students formed an organization called Students Take Action Now for Darfur (STAND), which, within three years, had established chapters at six hundred universities and high schools across the United States.

Back in 2001, I had written an Atlantic article describing the Clinton administration’s inaction during the Rwandan genocide. I later heard from a US official that President Bush had scribbled “Not on my watch” on a memo summarizing the article. Having always hoped to reach senior policymakers with my writing, I was moved by this, even as I wondered what it would mean practically. Inspired by the Livestrong anti-cancer bracelets, a group of activists created green wristbands inscribed with “Not On Our Watch,” which John and I joined thousands of people in wearing in an effort to raise awareness about Darfur. The year 2004 also happened to be the ten-year anniversary of the Rwandan slaughter, and, when the film Hotel Rwanda hit theaters, powerfully telling the story of Paul Rusesabagina, the hotelier who sheltered thousands during the genocide, many viewers looked to apply the lessons of Rwanda to the crisis under way in Darfur.