The End and Other Beginnings: Stories from the Future

It made me feel strange—weightless in places, like I was turning into tissue paper and butterfly wings.

“You think I didn’t care what they thought of me?” I shook my head. I couldn’t let him believe a lie about me, not now. “Of course I cared. I still can’t think about it without blushing.”

“Fair enough,” he said. “But I went to that party sophomore year because I found out you were going and … I wanted to get to know you. I loved this project. I loved everything you did in art class. I felt like you had showed yourself to me, and I wanted to return the favor.”

My cheeks felt a little warm. “You never said.”

“Well, you’ve said before that talking about old projects embarrasses you,” he said, shrugging. “So I never wanted to bring it up.”

“This is what I was worried about, you know,” I said softly. “About the medication. That it would mean I couldn’t do this—art—anymore. I mean, feeling things—feeling intense things, sometimes—is part of what drives me to make things.”

“You think you can’t feel better and do great work at the same time?”

“I don’t know.” I chewed on my lip. “I’m used to being this way. Volatile. Like a walking ball of nerves. I’m worried that if I get rid of the highs, and even the lows—especially the lows—there won’t be anything about me that’s interesting anymore.”

“Claire.” He stood, weaving through the chairs, and crouched in front of me, putting his hands on my knees. “That nerve ball isn’t you. It’s just this thing that lives in your head, telling you lies. If you get rid of it … think of what you could do. Think of what you could be.”

“But what if … what if I go on medication and it makes me into this flat, dull person?” I said, choking a little.

“It’s not supposed to do that. But if it does, you’ll try something else.” His hands squeezed my knees. “And can you really tell me ‘flat’ is that much different from how you feel now?”

I didn’t say anything. Most of the time I was so close to falling into the darkest, emptiest place inside me that I just tried to feel nothing at all. So the only difference between this and some kind of flat, medicated state was that I knew I could still go there if I needed to, even if I wouldn’t. And that place, I had told myself, was where the real me was. Where the art was, too.

But maybe—maybe that wasn’t where it was. I was so convinced that changing my brain would take away my art, but maybe it would give me new art. Maybe without the little monster in my mind, I could actually do more, not less. It was probably equally likely. But I believed more in my possible doom than my possible healing.

“It’s okay to want to feel better.” He touched my hand.

I didn’t know why—they were such simple words, but they pierced me the way music did these days. Like a needle in my sternum, penetrating to my heart. I didn’t bother to blink away my tears. Instead of pulling myself back from them, back from sensation entirely, I let myself sink into it. I let the pain in.

“But how can I feel better now?” I covered my eyes. “How can I ever … ever feel better if you die?”

I was sobbing the way he had sobbed in the car with me, holding on to his hands, which were still on top of my legs. He slipped his fingers between mine and squeezed.

“Because,” he said. “You just have to.”

“Who says?” I demanded, scowling at him. “Who says I have to feel anything?”

“I do. I chose you for one of my last visitors because … I wanted one last chance to tell you that you’re worth so much more than your pain.” He ran his fingers over my bent knuckles. “You can carry all these memories around. They’ll last longer than your grief, I promise, and someday you’ll be able to think of them and feel like I’m right there with you again.”

“You might not be correctly estimating my capacity for grief,” I said, laughing through a sob. “Pro-level moper right here.”

“Some people might leave you,” he said, for once ignoring a joke in favor of something real. “But it doesn’t mean you’re worth leaving. It doesn’t mean that at all.”

I didn’t quite believe him. But I almost did.

“Don’t go,” I whispered.

After that, I carried him back to the ocean, the ripples reflecting the moon, where we had treaded water after jumping off the cliff. The water had filled my shoes, which were now heavy on my feet, making it harder to stay afloat.

“You have makeup all over your face,” he said, laughing a little. “You look like you got punched in both eyes.”

“Yeah, well, your nipples are totally showing through that shirt.”

“Claire Lowell, are you checking out my nipples?”

“Always.”

We laughed together, the laughs echoing over the water. Then I dove at him, not to dunk him—though he flinched like that’s what he expected—but to wrap my arms around his neck. He clutched at me, holding me, arms looped around my back, fingers tight in the bend of my waist.

“I’ll miss you,” I said, looking down at him. Pressed against him like this, I was paper again, eggshell and sugar glass and autumn leaf. How had I not noticed this feeling the first time through?

It was the most powerful thing I had felt in days, weeks, months.

“It was a good story, right?” he said. “Our story, I mean.”

“The best.”

He pressed a kiss to my jaw, and with his cheek still against mine he whispered, “You know I love you, right?”

And then he stopped treading water, pulling us down into the waves together.

When I woke in the hospital room, an unfamiliar nurse took the IV needle from my arm and pressed a strip of tape to a cotton ball in the crook of my elbow. Dr. Albertson came in to make sure I had come out of the procedure with my faculties intact. I stared at her blue fingernails to steady myself as she talked, as I talked, another little dance.

The second she said I could go, I did, leaving my useless sweatshirt behind, like Cinderella with her glass slipper. And maybe, I thought, she hadn’t left it so the prince would find her … but because she was in such a hurry to escape the pain of never getting what she wanted that she didn’t care what she lost in the process.

It was almost sunrise when I escaped the hospital, out of a side exit so I wouldn’t run into any of Matt’s family. I couldn’t stand the thought of going home, so instead I drove to the beach and parked in the lot where I had once brought Matt to see the storm. This time, though, I was alone, and I had that strange, breathless feeling in my chest, like I was about to pass out.

My mind had a refrain for moments like these. Feel nothing, it said. Feel nothing and it will be easier that way.

Burrow down, it said, and cover yourself in earth. Curl into yourself to stay warm, it said, and pretend the rest of the world is not moving. Pretend you are alone, underground, where pain can’t reach you.

Sightless eyes staring into the dark. Heartbeat slowing. A living corpse is better than a dying heart.

The problem with that refrain was that once I had burrowed, I often couldn’t find my way out, except on the edge of a razor, which reached into my numbness and brought back sensation.

But it struck me, as I listened to the waves, that I didn’t want to feel nothing for Matt. Not even for a little while. He had earned my grief, at least, if that was the only thing I had left to give him.

I stretched out a shaky hand for my car’s volume buttons, jabbing at the plus sign until music poured out of the speakers. The right album was cued up, of course, the handbells and electric guitar jarring compared to the soft roar of the ocean.

I rested my head on the steering wheel and listened to “Traditional Panic” as the sun rose.

My cell phone woke me, the ring startling me from sleep. I had fallen asleep sitting up in my car with my head on the steering wheel. The sun was high now, and I was soaked with sweat from the building heat of the day. I glanced at my reflection in the rearview mirror as I answered, and the stitching from the wheel was pressed deep into my forehead. I rubbed it to get rid of the mark.

“What is it, Mom?” I said.

“Are you still at the hospital?”

“No, I fell asleep in the parking lot by the beach.”

“Is that sarcasm? I can’t tell over the phone.”

“No, I’m serious. What’s going on?”

“I’m calling to tell you they finished the surgery,” she said. “Matt made it through. They’re still not sure that he’ll wake up, but it’s a good first step.”

“He … what?” I said, squinting into the bright flash of the sun on the ocean. “But the analytics …”

“Statistics aren’t everything, sweetie. In ‘ten to one,’ there’s always a ‘one,’ and this time, we got him.”

It’s a strange thing to be smiling so hard it hurts your face, and sobbing at the same time.

“Are you okay?” Mom said. “You went quiet.”

“No,” I said. “Not really, no.”

No one ever told me how small antidepressants were, so it was kind of a shock when I tipped them into my palm for the first time.

How was I so afraid of such a tiny thing, such a pretty, pale green color? How was I more afraid of that little pill than I was of the sobbing fit that took me to my knees in the shower?

But in his way, he had asked me to try. Just try. And he loved me. Maybe he just meant he loved me like a friend, or a brother, or maybe he meant something else. There was no way for me to know. What I did know was that love was a tiny firefly in the distance, blinking on right when I needed it to. Even in his forced sleep, his body broken by the accident and mended by surgery after surgery, he spoke to me.

Just try.

So I did, as we all waited to see if he would ever wake up. I tried just enough to get the chemicals into my mouth. I tried just enough to drive myself to the doctor every week, to force myself not to lie when she asked me how I felt. To eat meals and take showers and endure summer school. To wake myself up after eight hours of sleep instead of letting sleep swallow me for the entire summer.

When I spoke to the doctor about my last visitation, all I could talk about was regret. The last visitation had showed me things I had never noticed before, even though they seemed obvious, looking back. There were things I should have told him in case he didn’t wake up. All I could do now was hope that he already knew them.

But he did wake up.

He woke up during the last week of summer, when it was so humid that I changed shirts twice a day just to stay dry. The sun had given me a freckled nose and a perpetual squint. Senior year started next week, but for me, it didn’t mean anything without him.

When Matt’s mom said it was okay for me to visit, I packed my art box into my car and drove back to the hospital. I parked by the letter F, like I always did, so I could remember later. F was for my favorite swear.

I carried the box into the building and registered at the front desk, like I was supposed to. The bored woman there printed out an ID sticker for me without even looking up. I stuck it to my shirt, which I had made myself, dripping bleach all over it so it turned reddish orange in places. It was my second attempt. On the first one, I had accidentally bleached the areas right over my breasts, which wasn’t a good look.

I walked slowly to Matt’s room, trying to steady myself with deep breaths. His mother had given me the number at least four times, as well as two sets of directions that didn’t make sense together. I asked at the nurses’ station, and she pointed me to the last room on the left.

Dr. Albertson was standing outside one of the other rooms, flipping through a chart. She glanced at me without recognition. She probably met so many people during last visitations that they ran together in her mind. When she turned away, I caught sight of her nails, no longer sky blue but an electric, poison green. Almost the same color that was chipping off my thumbnail. A woman after my own heart.

I entered Matt’s room. He was there, lying flat on the bed with his eyes closed. But he was only sleeping, not in a coma, I had been told. He had woken up last week, too disoriented at first for them to be sure he could still function. And then, slowly, he had returned to himself.

Apparently. I would believe it only when I saw it, and maybe not even then.

I set the box down and opened the lid. This particular project had a lot of pieces to it. I took the table where they put his food tray, and the bedside table, and I lined them up side by side. I found a plug for the speakers and the old CD player that I had bought online. It was bright purple and covered with stickers.

Sometime in the middle of this, Matt’s eyes opened and shifted to mine. He was slow to turn his head—his spine was still healing from the accident—but he could do it. His fingers twitched. I swallowed a smile and a sob in favor of a neutral expression.

“Claire,” he said, and my body thrilled to the sound of my name. He knew me. “I think I had a dream about you. Or maybe a series of dreams, in a very definite order, selected by yours truly …”

“Shhh. I’m in the middle of some art.”

“Oh,” he said. “Forgive me. I’m in the middle of recovering from some death.”

“Too soon,” I replied.

“Sorry. Coping mechanism.”

I sat down next to him and started to unbutton my shirt.

His eyebrows raised. “What are you doing?”

“Multitasking. I have to stick these electrodes on my chest. Remember them?” I held up the electrodes with the wires attached to them. They were the same ones I had used to show the art class my brain waves. “And I also want to stack the odds in my favor.”

“Stack the … Am I on drugs again?”

“No. If you were on drugs, would you be hallucinating me shirtless, though?” I grinned and touched one electrode to the right side of my chest and another one under it. Together they would read my heartbeat.

“No comment,” he said. “That’s a surprisingly girly bra you’re wearing.”

It was navy blue, patterned with little white and pink flowers. I had saved it all week for today, even though it was my favorite and I always wanted to wear it first after laundry day.

“Just because I don’t like dresses doesn’t mean I hate flowers,” I replied. “Okay, be quiet.”

I turned up the speakers, which were connected directly to the electrodes on my chest. My heartbeat played over them, its pulse even and steady. I breathed deep, through my nose and out my mouth. Then I turned on the CD player and set the track to the second one: “Inertia,” by Chase Wolcott.

Inertia

I’m carried in a straight line toward you

A force I can’t resist; don’t want to resist

Carried straight toward you

The drums pounded out a steady rhythm, the guitars throbbed, driving a tune propulsive and circular. My heartbeat responded accordingly, picking up the longer I listened.

“Your heart,” he said. “You like the song now?”

“I told you the meds would mess with my mind,” I said softly. “I’m just getting used to them, though, so don’t get too excited. I may hate the album again someday.”

“The meds,” he repeated. “You’re on them?”

“Still adjusting the dose, but yes, I’m on them, thanks in part to the encouragement of this guy I know,” I said. “So far, side effects include headaches and nausea and a feeling that life might turn out okay after all. That last one is the peskiest.”

The dimple appeared in his cheek.

“If you think this heartbeat change is cool, I’ll show you something even more fascinating.” I turned the music off.

“Okay,” he said, eyes a little narrowed.

I stood and touched a hand to the bed next to his shoulder. My heartbeat played faster over the speakers. I leaned in close and pressed my lips lightly to his.

His mouth moved against mine, finally responding. His hand lifted to my cheek, brushed my hair back from my face. Found the curve of my neck.

My heart was like a speeding train. That thing inside me—that pulsing organ that said I was alive, I was all right, I was carving a better shape out of my own life—was the soundtrack of our first kiss, and it was much better than any music, no matter how good the band might be.

“Art,” I said as we parted, “is both vulnerable and brave.”

I sat on the edge of the bed, right next to his hip, careful. His hazel eyes followed my every movement. There wasn’t a hint of a smile on his face, in his furrowed brow.

“The last visitation is supposed to give you the chance to say everything you need to, before you lose someone,” I said. “But when I drove away from here, thinking you were about to leave me for good, I realized there was one thing I still hadn’t said.”

I pinched his blanket between my first two fingers, suddenly shy again.

Heartbeat picking up again, faster and faster. “So,” he said, quiet. “Say it, then.”

“Okay.” I cleared my throat. “Okay, I will. I will say it.”

He smiled, broad, lopsided. “Claire … do you love me?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I love you.”

He closed his eyes, just for a second, a soft smile forming on his lips.

“The bra is a nice touch,” he said, “but you didn’t need to stack the odds in your favor.” He smiled, if possible, even wider. “Everything has always been carrying me toward you.”

I smiled. Reached out with one hand to press play on the CD player. Eased myself next to him on the hospital bed, careful not to hurt him.

He ran his fingers over my hair, drew my lips to his again. Quiet, no need for words, we listened to “Inertia” on repeat.

“I didn’t come here to skewer you,” she said, low and throaty. “Unless you give me a reason.”

She uncurled her fingers so the weapon would retract. It made a click click click as all the gears shifted, but she still heard its low hum as she brought her hands up by her ears to show she meant no harm.

She was in a bar. A dirty, hot one that smelled like smoke and sweat. The floor was covered in a layer of stale peanut shells, and every surface she laid a hand on was sticky. She had busted her way in the locked door a minute or two earlier, since it was much too early for the place to be open to customers, just shy of 10:00 a.m.

The only person inside it wasn’t human—which wasn’t a big deal, unless they were trying to pretend to be one. Right now they were standing behind the bar with a rag in hand, as if it stood a chance against the grime.

“Not afraid of getting skewered by some kid,” they said. If she hadn’t been who she was, she would have called them an average man, even a boring one. Their face was rough with a salt-and-pepper beard, and there was grease under their—very human-looking—fingernails. But they had all the telltale signs of digital skin: flickering when their eyes moved, a still chest, and a shifty quality, like they didn’t belong in their body.

“That’s too bad,” she said. “I find a healthy amount of fear improves somebody’s likelihood of survival.”

Flickering, flickering, as their eyes moved.

“What can we do to improve yours, then?” they said.

She smiled, all teeth. “Why don’t you take off your little costume so I can get a good look at you?”

The ET shrugged. Twice. The first time was a human shrug, a Whatever, if you insist. The second time was a bigger one, to shuffle off its digital skin.

For a time, as a kid, she’d thought the skin was just a projection, like a hologram. But Mom had explained that wouldn’t work—if it was a bigger creature, it would get itself into trouble that way—knock glasses off countertops, hit its head on doorframes, jab people with a spiked tail, whatever. The digital skin was more like … stuffing some of its matter into an alternate dimension. The skin was real, but it also wasn’t. The ET was here, but it was also someplace else.

She didn’t have to understand the science of it, anyhow. She just had to know what to look for.

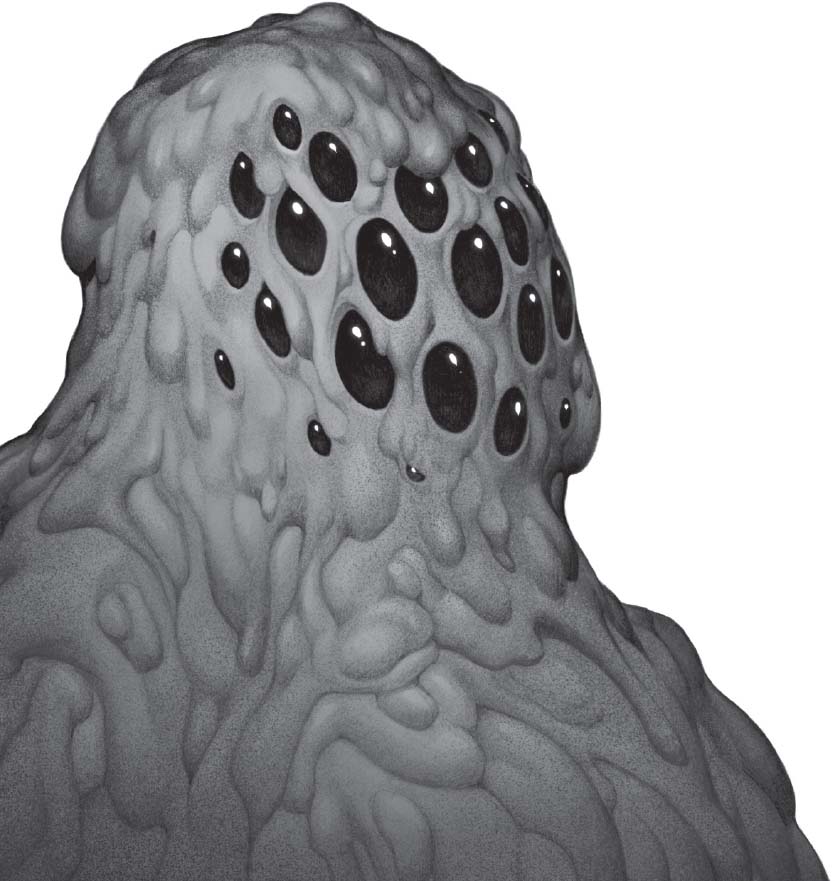

The ET burst out of its skin like stuffing coming out of a busted couch cushion. Matter bubbled up from the split, gelatinous and glowing purple-blue. For a second it just looked like a heap of purple crap, but then it started to take shape, a massive torso that oozed into squat legs, a bulging head without a neck to hold it up. And stuck on the front of that head like sequins from a Bedazzler, a dozen shiny black eyes.

The smell hit her next, like a cross between stinkbug and sulfur. It was lucky Atleigh had come across a few purpuramorphs last year, because she knew to keep her face passive. They were harmless unless you commented on or otherwise reacted to their stench. Then things could get ugly.

Well. Uglier.

“Thanks for obliging,” Atleigh said. “You know, most ETs don’t bother to wear a digital skin unless they’ve got something to hide.”

She lowered her weapon, slow, and slid it back into the holster on her belt.

“What is it that you want, kid?” the purpuramorph asked her, in a low rumble, almost subvocal. Purpuramorphs were one of the few offplanet races that didn’t need some kind of tech to speak like a human. Their vocal cords—buried somewhere in that purple mush—were actually similar to her own, somehow.

Atleigh took her phone out of her pocket and lit it up. On the screen was a picture of a woman with long hair—the same auburn color as Atleigh’s own. She had deep lines in her forehead, and a glint in her murky green eyes, like she was telling you to get to the goddamn point.

“You seen her? She was in here last week sometime.”

A dozen glittering eyes swiveled toward the phone, and Atleigh schooled her features into neutrality as a wave of odor washed over her, so pungent it almost made her eyes water.

“And if I have?”

“I just need to know if you spotted her talking to anybody,” Atleigh said.

“My customers are guaranteed a certain level of discretion,” the purpuramorph said. “I can’t go violating that just because some little girl asks me to.”

Atleigh’s smile turned into more of a gritted-teeth situation.

“First of all, I’m a little girl who can make your insides come out of you before you even notice it’s happening,” she said. “And second, that woman is my mom, and she’s dead now, so if you don’t tell me who she was talking to, I might do something out of grief that we’ll both later regret, get me?”

She rested the heel of her hand on the holster at her side.

“So what’s it gonna be?” she said. “Carrot, or stick? Because I gotta tell you …” She drew the modified gun, hooked her middle finger in the metal loop just under the barrel, and tugged on it so the mechanism extended the needle again. Click click click. “I’m pretty fond of the stick, myself.”

A couple of minutes later, Atleigh slid into the driver’s side of an old green Volvo, patted the urn buckled into the seat next to her, and started the engine. She knew exactly where she was headed next.

Atleigh Kent was a bounty hunter, and her bounty was exclusively leeches.

Not all extraterrestrials were leeches—in fact, 99.9 percent of them weren’t. Most of the ETs who settled on Earth were decent enough, and made things more interesting. When Atleigh saw pictures of the way her planet had been when there were only humans on it, she was always struck by how boring it was, all the same texture, like a bowl of plain oatmeal. It was better now, with beings of all shapes and sizes and colors, hearing half a dozen languages burbling or beeping or buzzing when you walked down the street.