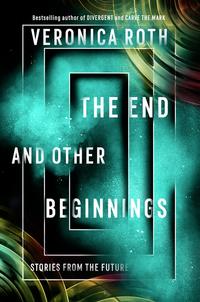

The End and Other Beginnings: Stories from the Future

She mostly dealt in the ones who had something to hide. Digital skin was illegal for a reason—mostly people wore it when they were on the run from something. But leeches …

Well. Leeches were a different story. They were a predatory race. They attached their silvery, centipede-like bodies to a person’s spinal cord and took control of their body and brain. As long as they kept the back of their neck covered, they could pass for human perfectly, absorbing the host body’s knowledge and experiences and integrating it into their new, joint self.

Meanwhile, the host suffered in silence, suppressed by the alien until they apparently fizzled out of existence. If the alien was attached too long, and then detached, the person was just a vegetable. Their bodies could go on living, if cared for, but their minds were gone.

All the alien races were vulnerable to leeches, but none more than human beings, their ideal prey. The easiest hosts to suppress, for whatever reason.

It had happened to Atleigh’s father. He—well, it hadn’t really been him, but they hadn’t known that at the time—had lived among them for weeks, dodging their mother and pretending at fatherhood. Then their mom had discovered the thing on their dad’s neck, and tried to stab it with a kitchen knife, and he had bailed.

They had gone on the hunt, as a family, the two little girls too young to remember much before the endless road trip their childhood turned into. Their mom had learned everything she could about the thing that had claimed her husband. It had taken her years to find him, in a lonely gas station in Iowa. Then she had ripped the thing off his spinal cord and gutted it. But their dad never came back to himself.

Atleigh had helped dig his grave, right there on the side of the road, by the mile marker, so they would always know where to find him. And since that day, she had been determined to save the human race, one leech at a time.

Lacey Kent’s hand went to her throat, to the buttons that fastened her collar closed. Just checking on them, as she had done a dozen times in the past ten minutes as she waited for the shuttle to reach the station.

There weren’t many students on the shuttle from the American Selenic Military Academy, and none that Lacey knew personally. A few teachers—including the famously volatile arachnoid, Mr. Zag—a few parents visiting ailing or troublesome children, a couple of fulguvore emissaries from their home planet, and of course, Lacey herself. She was in her sixth year, a secondary school transfer, so she didn’t quite have the posture that the lifers had—she could stand up straight, sure, but when no one was looking, she sagged like an old tree.

“Headed home, Ms. Kent?” Mr. Zag’s metallic voice asked. Arachnoids spoke through a complex system of pincer-clicking that no human had yet been able to decipher, so Zag had a voice box hanging from his pedicle. Even though the voice was computer-generated, Lacey thought she could hear some judgment in it. After all, she was going home in the middle of a semester.

“Yes, sir,” Lacey said. “My mother just died.”

“My condolences.” Zag’s pincers were clicking. Lacey had never gotten used to the sound. She hadn’t been in Zag’s class since her first year at the academy, but she still shivered when he spoke to her, the response Pavlovian. “Though perhaps it is some relief that you will not have to tell her—”

“I appreciate the sentiment,” Lacey said, cutting him off. She didn’t want to hear about all the things she wouldn’t have to tell her mother now, because it just reminded her of what she wouldn’t get to tell her.

Zag’s multiple eyes blinked at her, but he seemed to get the hint, and fell silent.

Finally the chime went off for docking, and Lacey went to the window to look down at Peoria, Illinois, one of the shuttle’s few stops. Peoria had once been home to a major machinery manufacturer that had later moved to the Chicago area. The population of the city had dwindled almost dangerously until the local government made a bid for one of the space academies. Now, by all accounts, Peoria was booming.

Lacey didn’t care much about the city either way. She wasn’t from there—wasn’t from anywhere, really, unless you counted the back of her mom’s old Jeep. Her official place of birth was a town in Minnesota, and even that was just a word she wrote on official papers, not a place she felt much tied to.

She spotted the wide stretch of the Illinois River, the bridge that spanned across it, and a cluster of low buildings before the shuttle docked at the station. Then she was heaving her bag—packed carefully so nothing would wrinkle—over one shoulder, and walking through the doors to search out her sister.

Atleigh wasn’t hard to find. Most families of human military students were downright proper, moneyed, all pressed collar shirts and shoes that made snapping sounds on tile. Atleigh was wearing dusty black boots—one with the laces fraying so the top of the boot was flappy around her calf—blue jeans, and a red plaid shirt over a gray T-shirt with a few holes in it. She had chopped off all her hair, so it was like a boy’s, with a wave in the front where it was a little longer. She was pretty without meaning to be, freckled by the sun, and taking too big a bite out of a Snickers bar, so it bulged in her cheek.

Nearby, a pair of uptight-looking primusars draped in diamond necklaces were giving her sideways glances—not subtle when you had stalk eyes that swiveled.

When she spotted Lacey, Atleigh grinned, and pulled herself off the pillar she had been leaning against. The two girls collided somewhere in the space between them, Atleigh’s hug “so tight the bears were jealous,” as their mom said.

Well, she wouldn’t be saying it anymore.

The sudden awareness of what she had lost—what they had both lost—kept hitting Lacey out of nowhere. She’d go along feeling all right, and then open a medicine cabinet and wham, her mom’s name was on the bottle of painkillers Lacey took for bad cramps sometimes. Or wham, she pulled on the black running shoes Mom had bought her for school.

The color of Atleigh’s hair, and the creases at the corners of her eyes.

“Wow,” Lacey said. And then, to cover it up: “Your hair’s gone.”

“Yup,” Atleigh said. She had swallowed the giant bite of Snickers, somehow. “Supposed to be a hot summer, so I thought I’d get ahead of it.”

Knowing Atleigh, that had nothing to do with the decision, but Lacey wasn’t going to pry.

“I’d offer to take your bag, but I don’t want to let those military school muscles go to waste.” Atleigh grinned. “C’mon, let’s get going.”

“How’s the car holding up?”

“Had to sell it.”

“What about the Jeep?”

Atleigh snorted. “Not gonna drive that gas guzzler on a perpetual cross-country road trip. It’s parked someplace outside Lansing. You can have it when you graduate, if you want it.”

Lacey followed Atleigh to a green Volvo with a rusty bumper. She opened the back door to throw her bag inside, and saw the urn buckled into one of the seats.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов