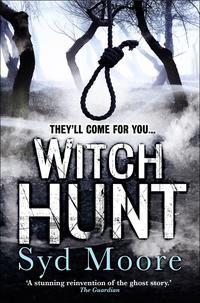

Witch Hunt

‘I’m Sadie, Rosamund’s daughter.’

The door trembled then opened to the length of the

security chain.

The smell of grilling bacon wafted out into the hall.

Dan’s neighbour squinted through the gap. ‘Where’s your mother?’

I gave her a taut explanation and the blue eyes softened a little. ‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘Thank you,’ I said. Standard response.

The woman regarded me with what I assumed was pity, then she sniffed and lowered her head and said, ‘I’ve heard things, you know.’

Most of us tend to gloss over non sequiturs like this but as a journalist, when people come out with lines like that, I’m always straight in there, probing. You usually find they’re spoken in unguarded moments – when the conscious, or the conscience, is struggling with the subconscious mind, and not guarding the ‘truth lobe’.

‘What things? Do you know where Dan’s gone, Mrs … Sorry, I don’t know your name?’

I held out my hand and took a step towards her. It completely backfired. The woman took a step back and her door slammed shut.

I hung about for a couple of minutes, waiting to see if she was going to open it again, then shrugged mentally and put the neighbour’s words down to old age or battiness and left.

As I crossed the ground floor foyer I passed a tall man in a black leather jacket with a remarkably expensive-looking tan, not the kind you get from living in the UK. Or out of a bottle for that matter. And, believe me, I’m from Essex – I know.

He smiled as if he knew me. That kind of reaction wasn’t uncommon: Leigh was a small town, people tended to know of each other, even if they hadn’t yet met. I nodded back.

As I approached the large glass doors at the front, the tall man skipped in front of me. He smiled again, this time revealing perfect white teeth and a pair of intense blue eyes, then he held open the door for me. ‘Ladies first.’ There was an accent there, though the exchange was too brief to pinpoint it.

‘Thank you.’ I stepped through it and continued over to my car expecting him to follow me out.

He didn’t.

As I swung out of the car park I saw him behind the glass door.

I couldn’t swear to it, as I was a fair distance away, but I think he was watching me.

Back at the hospice, I found Sally.

‘I think it’s all right to take them,’ I told her and handed over the bottle. ‘There was another one there of the same. I know Dan usually has a lot of spares in case he mislays the meds. He’s not going to run out for a good while.’

Sally heaved a sigh. ‘It’s all been very stressful for poor Dan. You’re managing to cope, Sadie. You’re young and have friends and your dad. Dan’s pretty much on his own and I think he might not be handling this too well.’

I had been so wrapped up in feeling sorry for myself and Mum that it hadn’t occurred to me what Dan might be going through. Now I saw Sally could be right. I remembered a conversation I had once with him about his medication. He described the drugs as creating a ‘semi-porous wall’ which managed to keep out what he referred to as ‘the dark’. ‘Sometimes,’ he told me, ‘it’s just not strong enough.’

‘What do you do then?’ I asked him.

‘We go back to the doctors,’ Mum interjected.

What with everything that had been going on lately, I doubted very much that Dan had thought about making an appointment.

‘Oh God,’ I said. ‘I never thought of that. It’s been a very difficult time. I’ve been completely self-obsessed.’

Sally’s eyes crinkled into deep lines around the corners of her eyes and across the top of her cheeks.

‘Don’t beat yourself up about it, love. You’ve had your own cross to bear.’ She smiled gently. You could tell she did that a hell of a lot. The pattern of lines was etched deeply into her face through years of usage.

She held the bottle up to inspect then said, ‘Dan might have taken some time out to get his head straight. Then again, he well might have relapsed. If you’re not acting rationally, then you don’t think things through logically. Stress makes people react in different ways.’

‘Yes,’ I nodded. Now Sally was putting it like that, it did seem like the reasonable conclusion – Dan was probably taking a break. Perhaps he was running away. Maybe he was being cowardly. But perhaps that was necessary in order to preserve his own sanity. If I knew Dan, and I thought I did, whatever he was doing, he would have seen it as imperative.

Sally grunted at the pill bottle. ‘Forty milligrams. Not sure about that. Doesn’t look like a forty mil dose. Never mind,’ she shook the bottle and popped it on the shelf behind her. ‘I’ll ask Doctor Jarvis to advise.’

With a sense of unease I said my goodbyes and hurried home.

Chapter Five

The landline answer phone was flashing when I finally got back to the flat. It was a message from my dad, checking in on me to see how I was going. Lots of people were doing that. I didn’t phone many back. It was weird – although I wanted to be able to talk about it, I didn’t want to talk about it. I guess I just needed to know I had the option.

However, I should return Dad’s call at least.

I picked up the phone, hit ringback and got my stepmum, Janet, who informed me Dad was putting the kids to bed and would probably be another fifteen minutes. I said I’d call back in the morning and that, no, it wasn’t urgent.

‘You’re still coming on Saturday though, aren’t you?’ Janet wanted to know.

Saturday, Saturday. What was on Saturday? I reached into my handbag and pulled out my diary. ‘Wouldn’t miss it for the world,’ I told her, still unsure of what I’d committed to.

‘Good, good. I know it’s a fair way. Your dad will appreciate the effort.’

‘Right. Of course,’ I thumbed through to Saturday’s entry – Uncle Roger’s birthday. I groaned.

‘Mercedes?’ Like my father, Janet too had developed the annoying habit of calling me by my full name.

‘Sorry, Janet. I had forgotten. I’m sure he wouldn’t miss me if I didn’t come.’

‘Mercedes, honestly! Don’t say that. Your dad certainly would. You know you’re the apple of his eye.’

I managed to stifle a snort of contempt. This was pretty typical of lovely rosy Janet, but a blatant lie. Dad had always been a remote sort of parent, though not unloved or unloving. But the emotional and physical distance increased when he and Mum split and he moved out of our home back to his native Suffolk. I’m not being self-pitying when I say he never appeared particularly interested in me. True – he did the regular check-up and monthly phone call thing. And true – it didn’t bother me one iota. But then my half-sisters, Lettice and Lucy, came along.

Janet was a homely and family orientated woman. A fair-haired big old farmer’s wife type, who insisted that I got more involved with the family. When I did, I saw that Dad absolutely idolised his new daughters with an affection that was doting. It was different to the parenting style I’d known, for sure. But to be frank, I couldn’t blame him: Lettice and Lucy were cool. Fourteen and eight years old respectively, and completely feral. Borderline punk. I liked their attitude.

I think a lot of their wildness came from living in the country; after he left, Dad bought a row of dilapidated cottages in the middle of nowhere. He did the first one up and moved into it whilst renovating the rest, then sold them on, retaining three of them to rent.

It was a canny move. Over the past couple of decades the ‘middle of nowhere’ had transformed into ‘desirable rural location’, affording him a very comfortable early retirement.

‘Mercedes? Are you still there?’ Janet’s voice brought me into the present. Oh yeah, the birthday party.

I made a snuffling noise.

‘Oh come on, love. Uncle Roger might not be around for much longer. His kidneys aren’t looking good.’

Dad’s rather morose older brother was a permanent downer at any festive occasion.

A small sniff conveyed my cynicism. ‘He’s been saying that for years.’

‘Yes, well now it looks like he’s right.’ Janet made it sound like a final reflection, demanding of compassion.

I sighed audibly. She changed tack. ‘It’d do you good to get away. And everybody’s expecting you. The kids are looking forward to seeing you and you know how upset your Dad will be if you don’t …’

‘Okay, okay. I’ll be there. I’ll only stay for a couple of hours though.’

‘That’s perfect. Thank you. See you Sunday then. One p.m. Try to be prompt.’

I hung up.

It wasn’t that I didn’t like visiting Dad. It was just with everything going on at the moment …

Though I didn’t want to think about any of that. Instead I decided to distract myself with some brain candy so I dumped myself on the sofa and flicked on the TV. Out of habit I surfed through to my preferred twenty-four-hour news channel.

There was some kind of kerfuffle outside County Hall. I couldn’t get what was going on at first then, as the report built up the eyewitness accounts, I sussed that Robert Cutt had been visiting and got an egg in the face from a couple of bystanders protesting about media monopolies.

The mere image of him flashing up on the screen made my stomach tighten. Though he’d moved to England in his thirties, his white-blond hair accentuated a classic American face: fantastic cheekbones, wide jaw, good teeth and eyes that showed hyena-like cunning mixed with the blank dumbness of a circling shark. Sometimes in a certain light, it looked like there was nothing going on behind those startling peepers. Like the man had long said goodbye to his soul.

Yet none of this did anything to detract from the overall effect; even his most vociferous opponents had to admit that Robert Cutt was a very handsome devil indeed. Regrettably the well-groomed exterior and contrived panache concealed a business savvy that was ruthless and pretty unethical in its hunger for power.

I couldn’t help thinking, as I watched the sixty-something politician brushing away the cameras, that despite the egging he looked rather pleased with himself. It was gross: there was something about the man that really creeped me out. It wasn’t just the fact that, a few months ago, he’d been coaxed into revealing in a rather probing and frank interview that he believed that men were infinitely better adapted to leadership than the female of the species. Following on from that another documentary had revealed his friendship with TV evangelist, Pat Robertson.

I knew about Mr Robertson before I had ever heard of Cutt: a friend once bought me a joke present for my birthday. It was a mug that had one of Mr Robertson’s quotes printed on it. It read: ‘The feminist agenda is not about equal rights for women. It is about a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practise witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians.’

Bless his little cotton socks.

After that documentary Cutt did a fair bit of political manoeuvring to put a respectable distance between their camps. Even so, there were similarities; both advocated a stable family should have a mother and father (one of each sex). And there was an insidious suggestion that women should remain within the home, though it wasn’t stated explicitly. Nor was it their conviction that human nature was ever nurtured. It was more about genetics and nature. But that was easy for him to say, coming as he did, from a line of pilgrim Baptists back in the good old US of A. Mr Cutt made a big deal of those roots and set himself up as something of a paragon of ancestral virtue.

God knows how he came to be a political contender in the UK.

And yet, it was none of that that had me reflexing into gag response when I saw his nauseatingly beautiful face. No. It was something about his eyes. The hard grey circles reminded me of someone.

I’d just never been able to put my finger on who.

I almost convulsed with repulsion as the screen showed him ushered by bodyguards into a black BMW: just before he got in, he waved a two-fingered victory sign at reporters.

The scene had dulled my mood, leaving me with a restlessness that I couldn’t counter. I switched channels trying to find some comedy. Unfortunately the smarmy mogul had dampened me, so I cut my losses and retired to bed.

I was just sinking into a light slumber when I heard that noise again: a scratching followed by a creaking of sorts. When I strained my ears, I could tell it was right above me, in the loft.

I groaned and buried my head under the duvet, underlining my mental note to call pest control in the morning.

But it got louder.

I pulled the duvet down from my face and stared at the ceiling. ‘Shut up,’ I yelled at it.

Magically, the shuffling stopped.

Chapter Six

The offices of Portillion Publishing were on level six of the larger umbrella company’s head office. The sleek glassy building had won several architectural awards for innovation and was set in the financial heart of London. I use the term ‘heart’ loosely: it was at the centre of the complex of roads and warrens that calls itself the City of London. I’d never felt comfortable about being in that place, with all those bankers. The lack of vegetation, the inhuman scale of the buildings, the overriding predominance of grey, the uniform of suits, the set pace of walking, all combined to give the impression that when you got off the train at Fenchurch Street, you entered a mechanised world set up purely to produce money. Don’t get me wrong, I didn’t have a problem with the individuals as such – some of my best friends worked in the City – but en masse, the whole set-up was overwhelming.

As I walked towards the river, I had the sense of being swallowed up or, perhaps, it was more like joining in. Whatever, I was almost relieved as I went through the revolving doors of Cutt’s castle.

Portillion Publishing was originally situated in Mayfair, but when the mogul acquired it, the outfit was ‘streamlined’. Accusations of asset stripping and general nastiness were flung around but faded once the concern was relocated to this nerve centre. It was enormous, shaped like a glimmering spire: a cathedral to Capitalism.

The offices came off an inner courtyard that had the full height of the thirty-five-storey structure. Large glass elevators reached skywards to the ceiling where a crystal pyramid capped the top. Chrome fittings and mirrored pillars amplified the light. The effect was dazzling.

A tall, willowy PA in a black designer suit collected me from the reception area. Her chic asymmetric bob and red lipstick were so impressive I felt immediately underdressed in my beloved vintage dress and boots. To cover up my nerves I tried to make small talk as we walked towards the lifts.

‘This is a fantastic building,’ I gestured upwards. ‘So much light.’

Delphine, as she introduced herself, sniffed. ‘Yes. It’s a great place to work.’ Her voice dragged with vague ennui.

‘Is Cutt based here?’ I asked, following the tap-tapping of her kitten heels across the marble floor.

‘Mr Cutt’s office is there,’ she indicated a large tinted glass window that covered the whole of one side of the first floor.

‘All of it?’

Delphine managed to crack a smile. ‘It’s an expansive concern.’

His office directly faced the entrance, security checks and reception. ‘He gets a good view of everybody coming in

and out that way, I suppose.’

‘Oh, Mr Cutt is an extremely energetic man. Not one to drop the ball. Robert likes to keep his eye on things.’

‘Quite literally,’ I said and stitched on a chuckle. ‘He can more or less see everyone from that vantage point.’

She didn’t reply.

The short journey upwards was uncomfortable. We stood either side of the lift doors staring out of the glass sheets. Delphine didn’t speak and I didn’t bother to try any more conversation. She was one tough nut to crack, I thought silently, tension creeping along my shoulders as I contemplated the kind of fella this Felix Knight might be. His email had an old-fashioned jauntiness to it that had me picturing a white-haired man in his fifties, in a sort of geography teacher get-up – leather-elbowed tweed jacket and cords. But after the intimidating pillar of reserve that was his secretary, I was beginning to think he was probably more of a reptilian guy. To command authority over Delphine, he’d surely have to be older, wiser and far, far colder.

Both my visions were wrong. Felix Knight turned out to be a phenomenally friendly sort. My age, or possibly younger. He had fantastically clear skin that gave the impression he was fresh out of the shower. Despite an impeccable tailor, the rest of him was a little unkempt; his hair was a mass of carefree brown curly waves, week-old stubble was spread across a firm jaw. I wasn’t surprised he hadn’t shaved – you could cut yourself on those cheekbones. He had a very very wide smile that wrinkled up the sides of his eyes. Out of the context of the publishing house and out of that suit, he could easily have been an actor or an academic, or, because his build was tall and fairly broad across the shoulders, maybe a young farmer. There was a slap-happy aura about him that immediately put me at ease.

And he was rather attractive too.

We shook hands. His was a firm super-confident grip, his eyes incredibly sparkly.

‘Do come in, Miss Asquith.’ He pulled a chair out and helped me into it. Well-spoken but not intimidating, his body language communicated both bonhomie and impeccable manners. He thanked Delphine and asked her to fetch some coffee, ‘if it is no trouble. Otherwise,’ he said, ‘I’ll hit the canteen.’ Delphine assented with a nod and so Felix slipped round to the other side of his desk and plopped into a high-backed chair. I saw him steal a glance that swept over me from the top of my head downwards, taking in bust size, hips, and legs. For a nanosecond he lost his self-possession, as if surprised by some aspect – I didn’t know what. Was it the vintage dress? Knee-high boots? Leather jacket? Perhaps he’d expected me to rock up in a suit. Well, tough, I thought, that ain’t ever gonna happen. Anyway, it was fleeting: Felix Knight mastered himself so quickly the blunder was barely perceptible.

‘Well,’ he said brightly. ‘I’m so pleased to meet you at

last.’

At last! He only introduced himself yesterday. But then again, the handover from Emma had probably occurred a couple of weeks ago. It was only I, the author, who had learned of Portillion’s plans twenty-four hours ago.

I told him I too was pleased to make his acquaintance and made myself comfortable in a jazzy chrome and leather chair.

The offices of Portillion Publishing were kitted out with an array of gizmos and screens, all carefully selected to compliment the vast oak bookshelves displaying some of Portillion’s top-selling authors.

‘I’m sorry that Emma had to take off so quickly,’ he said once he was seated back behind his desk. I watched him casually cross his legs, his large right hand smoothing over a wrinkle of fabric around the kneecap. He coughed and smiled. ‘These things tend to move rapidly once decided. However let me assure you I am very impressed by your proposal and can’t wait to read the first instalment.’ I liked the way his tongue lingered over the ‘r’s in a breathy maybe Irish, though more likely American style. Unlike other media types I’d encountered who aped the linguistic idiosyncrasies of the Super Power to evoke a cool cosmopolitan image, Felix’s accent sounded genuine. I guessed he was well travelled.

‘That’s great, thanks, Mr Knight.’ I nodded vigorously to match his level of enthusiasm.

He swung his chair and placed his hands on the desk. ‘Oh please,’ he said, lowering eyes and voice simultaneously. ‘It’s Felix.’

Bloody hell – was he flirting? No. Couldn’t be. Not on a first date. I noted my Freudian slip and corrected ‘date’ to ‘meeting’. It must just be that old public school charm offensive.

‘And actually, my friends call me Sadie,’ I said, and squeezed in a little self-conscious grin.

He stroked the skin behind his jaw and regarded me with a grin. ‘So, formalities over – how have you been, Sadie?’

It threw me a little. Was this publishing getting-to-know-you-speak? Or had he heard about my recent loss?

‘Well,’ I squigged myself forwards onto the edge of my seat, so that I could sit up straight and suck in my stomach. ‘I’m very pleased about the publishing deal. It’s come at a good time. You see, my mother passed away a couple of weeks ago …’

‘Oh I’m sorry,’ he said and assumed a concerned bearing; eyes down, head cocked to one side. I’d seen it before. It’s what people did. Felix went a step further and clasped his hands, his eyebrows pointed towards his nose. It was a sincere expression. ‘Was it sudden or … ?’

‘She’d been ill. But well, you’re never prepared for it, are you, no matter how expected?’

He glanced away and back again quickly. ‘Condolences to you and your family. That can’t have been easy …’

‘Thank you, I said and moved on. I wasn’t comfortable with this. I didn’t want to start my new career with negativity. ‘So, as you see, I’m ready to get on with the book right away.’

‘And I am certainly not going to stop you,’ he said, and his face began to shine again. ‘Shall we clear up the formalities and head off for a bite to eat? I don’t know about you, but I’m famished.’ He sat back and touched his stomach. It looked as hard as a board.

‘Starving Marvin, as they say in South Park,’ I said and immediately regretted the crass pop culture reference.

‘Quite,’ said Mr Knight. He reached for a document at the side of his desk. ‘We’re all quite enamoured of your colloquial style. You don’t come across writing like that very often. Wondered if you’d speak like it too. So often you get authors who write in one way and speak in quite a different manner. But you seem to be the genuine article.’

What was that meant to mean? Genuinely working-class? Genuinely Essex? I didn’t want to risk offence by asking for clarification so simply smiled. Felix did too – that wide gleaming grin (no overbite, white pearls verging on perfect), displaying zero visible dental work, evidence of good, strong, well-nourished stock.

He selected a pen and pushed the wad of papers towards me. ‘Let’s get your signature down here. Then we can release the funds.’

The restaurant was Spanish, full of little round tables. Across the walls hung strings of what I first thought were tacky plastic garlic bulbs and chillies, but then realised were the real McCoy.

After signing the contract Delphine popped in to let us know our taxi had arrived and since arriving at the restaurant our conversation had spun away from work into taste in food. It was only after we’d knocked back our first glass of wine that we got down to nitty-gritty book talk.

I explained that I’d already written an introduction about the factors that led up to the witch hunts, then, developing my original proposition, outlined the fact I was planning on setting the work out in three sections: the hunts up to 1644; the Hopkins campaign of terror; and then the decline of prosecutions up to the last known arrest of Helen Duncan, aka ‘Hellish Nell’, who went down for witchcraft in 1944, if you can believe that. Hers was an odd case. She was convicted of fraudulent ‘spiritual’ activity after one particularly informative séance in which she gave out classified information about military deaths. I had to include it. Felix was fascinated. Or at least, he gave the impression of being utterly absorbed; the eyes zoomed in on my face, his mouth set into a line. His expression was neutral, listening, but there was a shadow of a wrinkle across his forehead which betrayed intense concentration.

Enjoying the attention, I went on to explain I had pretty much sketched out the first section and was now focusing on Matthew Hopkins.