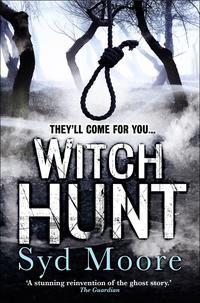

Witch Hunt

I can’t remember what the joke was about but I have a distinct recollection of laughing till I cried.

Which was good, as there was a hell of a darkness on its way.

Chapter Eight

I didn’t stay long at the pub. Usually I don’t work after I’ve had a drink but tonight, the excitement from my meeting with Felix was carrying me through.

I spread out my file of notes. I wanted to go back over the first section of the book to check that I’d got everything I wanted in there.

There was a hell of a lot to cover. The first few trials were pretty small fry, the convicted, either being fined or pardoned. Most of their crimes centred round causing livestock to fall ill, or in several pitiable cases, children. But then there was the Hatfield Peverel outbreak, with Agnes Waterhouse the first person to be put to death as a witch. Her daughter was also accused but turned witness against her mother and was found not guilty. Agnes allegedly confessed to being a witch. Her primary crime was owning a cat, who she talked to often. Its name was Sathan. Not the most sensible choice for an old woman living on her own in sixteenth-century rural Essex.

The hanging of Agnes Waterhouse set a precedent, and soon more and more women were executed. Mostly for ‘bewitching’ people to death. In 1582 in St Osyth fourteen were indicted. Of these, ten were found guilty. Ursula Kempe was accused by her eight-year-old son, whose testimony led to her execution and Elizabeth Bennet’s. In 1921 two female skeletons were found in a St Osyth man’s back garden. They had been pinned into the ground with stakes and iron spikes had been driven through their elbows, wrists and ankles. They were thought to be the remains of the two women and were bought by collectors in the nineties, for exhibition in their private collections. Imagine that – your remains bought and sold, then put on display for the rich to gawp at. I couldn’t imagine the women rested in much peace.

Then there was the sad case of Avice Cony. She and her sister and mother, Joan, were all charged with causing a number of people to die. Avice’s son was made to give evidence against her in the trial and, consequently, praised by the judge. Though he was only ten, his testimony sealed their fate. They were all found guilty. Joan Cuny, Joan Upney and Joan Prentice were executed within two hours of sentencing. Avice declared she was pregnant and was examined. After her claim was validated she was thrown into gaol until she gave birth. Then she was hanged the next day.

It was a shocking story, but one that was repeated time and time again. I noticed that I’d left the date off that last trial and, rather than sift through reams of notes, googled it. 1589. I wrote it in my notebook to insert in a minute.

When I replaced my hands on the keyboard an unwelcome sight greeted me: a private messaging box. Facebook had opened itself.

‘I’m sorry,’ the words in the rectangle read.

I picked up my biro and tapped it on the side of the table. Again, there was no name to note at the top of the box.

‘Little git,’ I thought.

‘Are you there?’ Same question as before.

I knew Joe had told me not to reply but part of me wanted to find out more details so I could trap the teenage tinker. Before my weakling impulse control was able to kick in I saw myself write, ‘How old are you?’

There was a pause, then, ‘You know. 15.’

A teenager in his bedroom. Joe was right. But this prankster was obviously rather thick too. He shouldn’t have responded. Now I had some info about him.

Would he be foolish enough to reveal more?

I tried it. ‘Where are you?’

Another pause. Then, ‘You know.’

The temptation to respond was overwhelming. Perhaps I could draw him out and hand over the details to Joe. ‘I don’t,’ I wrote.

Would he bite?

I waited for a moment then it came up: ‘I’m right here with you.’

A trail of goosebumps crept down my spine.

Hadn’t seen that coming.

I took my cursor to the ‘x’ and shut messenger down, silently cursing myself for playing right into his sweaty hormonal hands.

Still, I had to admit, it was a little unnerving. I pushed back from the table and went to look out the large front windows. There were no houses opposite, only the meandering curve of the grassy hill; the brownish silhouette of the station bathed in the orange half-light of the street lamps. I directed my gaze to the west. From this angle I could just about see a foot or two beyond the periphery of several balconies. To my left, the house next door bulged out. The upstairs windows were dark. I knew the old couple who lived there, Mr and Mrs Frenten. They were in their eighties and totally benign. I couldn’t see them trying to freak me out like this.

I turned back and, from my vantage point by the window, surveyed the room. The table was about four foot away. My laptop was turned into the room, so that when I worked I could take eye-breaks on the view.

There was a thin side window that looked over the flats to the west, but it was further back into the room and so narrow no one could see in. Even so, I had a good look out of it. The view was limited. Directly opposite, a frosted window was fogged up with condensation. A small round opening beside it billowed out steam. Someone was having a late shower.

There was no one who could see me at my computer.

Okay, well, I guessed it was the right time for a break. I got up and went into the kitchen. It was too late for proper coffee so I fixed myself a nice steaming instant and returned to the living room.

I stopped halfway across the room.

It was there again on the screen.

I sucked in some air and walked tentatively to the computer.

‘I’m sorry,’ it read.

Nope. Not having it. I scrolled down and disabled my internet connection. Bugger off.

Then I plonked down my coffee and returned to work. Where was I? Oh yes, 1589. I flipped into Word and inserted the date at the beginning of the paragraph.

The message box appeared on the screen. ‘I’m frightened.’

Quickly I checked my connection. The line was flat. I should be uncontactable.

‘I can feel him here.’ The words tripped across the box. ‘I can smell him.’

I didn’t want to answer it but that familiar sense of pity, alarm, was returning.

I tapped out ‘Who?’

‘The Devil.’

Right, too much. I slapped my laptop closed. Shit. My hands had a shake to them.

Now what? I stood up and took my cup to the mirror above my old seventies fireplace. My eyes were wide. A tight line fixed across my forehead like an arrow.

Screw it. I went to the table and picked up my phone.

Was I being stupid?

Probably.

He was slower to answer than before. ‘Evening.’

My voice was higher than usual, full of restless energy. ‘Hi Joe. I’m sorry to disturb you. I hope it’s not inconvenient, it’s just that, you know what I was talking about the other day? Well, it’s happened again. But,’ I faltered. ‘It’s more threatening now. They said that they’re here with me. And I took my laptop offline but the messaging continued …’ I was speeding through the explanation like a lunatic.

‘Hang on. Slow down. You’re on speakerphone. I can’t hear you.’

I waited a minute then took him through the details, describing the specifics of disconnecting from the internet.

‘That can’t happen, Sadie.’

‘I know.’

The connection cracked and buzzed. A horn blared down the line. He was driving.

‘Look, I’m busy tonight but I can pop round tomorrow afternoon and you can show me. How does that sound?’

I nodded then realised he couldn’t see me. ‘Yes please. I’ll be home by about three. Thank you.’

‘In the meantime, get off your computer and have an early night or something. You sound tired.’

I was. I suddenly so was. I said goodbye and took his advice.

It took a while to get my head down, what with the scratching up above, but once I was gone, I was well gone.

Chapter Nine

Impossible pain racked my abdomen. Coming and going in waves. Blackness all around me. Wind howling. Wet mud. It was coming again. The pain burnt through me like a flame forcing a scream from my lips: ‘No!’

I couldn’t stand it. The spasms were beyond anything I had known before, racking me, taking me, unloosing a howl that came from the depths of my soul.

‘Oh God. Mother. No.’

I woke myself up screaming it.

Another nightmare I couldn’t remember, only the lingering sting of agony.

My hair was plastered against my forehead, nightdress twisted up around me. I pulled it down and saw my hand left a red trail.

Lifting the duvet gingerly I found myself drenched in blood. What? I wasn’t due on for another two weeks. Though I suppose everything had gone a bit haywire after Mum. I hadn’t been eating and I hadn’t been sleeping so well.

It was earlier than I normally got up which was lucky as I had time to bundle my sheets into the washing machine and jump into the shower. Though I couldn’t dawdle: my interview was in North Essex.

I popped a couple of ibuprofen and downed a bitter coffee then dragged my sorry arse out of the flat and into the car, submerging my nightmare in music.

Beryl Bennett was one of those women whose age is hard to determine. She had the manner and wrinkles of a septuagenarian but the sleek brown hair of someone much younger. Her make-up, too, was quite contemporary – subtle beige eyes and a hint of bronzer under the cheekbones. Essex women always take care of themselves. Still, readers liked to know how old people were so I’d have to ask. That’d be tough on her, I thought as she put the kettle on. Though what with one thing and another, I never did find that out.

I knew this wasn’t going to need a lot of effort – it was just a puff piece for the Essex Advertiser on Beryl’s and her son, David’s, fundraising efforts for a children’s leukaemia charity.

I liked these little jobs. Back when I was doing news, up in the Smoke, it was so much harder; the questions more intrusive, the scenes more distressing. Down here in the suburbs and countryside, I found it quite refreshing that they filled up pages with news and events that, however mundane they might appear, actually testified to human compassion and community spirit.

David Bennett sat opposite me at the kitchen table. He was in his late forties. A thickset man with thinning grey hair and a brown jersey pulled over the beginnings of a good beer belly. There was something in the way he moved about the semi-detached house and interacted with his mother that made me feel sure he’d never left home. When I pulled the wooden chair back to take a seat it made a squeaky noise. David made a naff joke about farting and cracked up. He had the kind of unashamed chortle that sounded well practised in the art of laughing alone. Beryl appeared to have given up being embarrassed years ago. Much as she obviously loved her son, she made no attempt to hide an outstanding ability to filter out his crap gags and howlers. Selective deafness, I think they call it.

‘Be a dear,’ she called to David. ‘Fetch out the biscuits.’ He instantly obeyed Mrs Bennett and went to one of the units in the corner, producing a lurid floral biscuit tin, the like of which I hadn’t seen since the seventies.

The kitchen was decorated similarly; a pretty room, with poppy-patterned curtains that hugged a large window to some cutesy rear garden, complete with plastic flamingos. David plonked the tin on the table. ‘Garibaldi, Miss Asquith? Or perhaps a baldy Gari?’ He laughed alone.

I smiled politely. ‘Lovely, thanks,’ and took a biscuit. ‘Please call me Sadie.’

‘Lady Sadie?’ he asked.

‘Just Sadie,’ I told him.

‘Maybe Sadie.’

I said nothing.

The corners of his mouth drooped when he saw I wasn’t picking up the ball with this one. ‘So,’ he said, changing the subject. ‘I’m afraid we haven’t got the big cheque any more. Is that okay? Your photographer came on Monday and took some photos of us holding it.’

I shook my head. ‘No, that’s fine. We don’t need it. This is just for me to ask a few questions for the piece. Make sure I’ve got all the facts right.’

‘Well, we appreciate you coming down, dear,’ said Beryl, setting out a tin tray with cups and saucers. ‘I know John is grateful.’

‘Right,’ I said and took my notepad out of my bag. ‘So that’s John who?’

David leant forwards as he spoke. ‘John Adamms. Two “m”s.’ He watched me write them down.

‘And how does John fit into this?’

‘He’s Polly’s dad,’ Beryl called out as she opened the fridge and took out the milk.

‘I see. And Polly is the little girl that died?’

‘That’s right,’ said David. ‘We were all very moved. That’s why we decided to raise some money.’

Beryl brought the tray over to the table and lifted the cups, milk jug and teapot onto the lace doily in the centre. ‘Tragedy. Life is full of it. Milk and sugar?’

‘Just milk please. And so how do you know the Adamms?’

Beryl heaved herself into a chair. Her thin, wrinkled hands passed me a cup of tea then nudged David’s towards him. ‘They’ve been part of our group for a while now.’

‘And what group is that?’

‘The Hebbledon Spiritualists.’

‘Oh,’ I said and looked up. No one had mentioned anything about nut bags. I’d assumed it would be your usual sponsored walks and coffee mornings. No wonder the staff writers had farmed it out.

Beryl noticed my reaction and grinned. ‘We’re not screwballs, you know. Quite your everyday sort of people. We have accountants in our group, PAs, bus drivers. Bob’s a fireman.’

‘And we have a Postman Pat.’ David grinned.

Beryl smiled at him with the sad acceptance of parental disappointment.

I made a note about the Spiritualist group. ‘So how did you raise the money? It was a fair bit wasn’t it – a thousand pounds?’

David replaced his teacup into the saucer and leant towards me. ‘£1050,’ he said and watched me write it down again. ‘It was £1031.75. I made it up with my own money. People like nice round figures.’ He looked at my notepad. I didn’t write it down.

‘Wow,’ I said to Beryl. ‘Not bad.’

Mrs Bennett tested her tea with her tongue. ‘We’re getting more of the general public coming along to meetings now than ever before. But believe it or not, there are still a fair few people out there who have some odd notions about Spiritualism.’

No kidding, I thought. ‘Really?’ I said. ‘In this day and age …’

‘Yes, I know.’ Beryl made a tutting noise with her tongue and rolled her eyes. ‘So, we thought, well, why don’t we do some open evenings? Get local people in so they could see we were just ordinary people – doing our stuff to help others out. And of course we wanted to raise money for Polly’s charity.’

‘Mum’s a medium,’ David said. ‘Very talented too.’

‘I do my best,’ said Beryl, a proud little grin appearing on her lips.

‘Right,’ I said. ‘Is that what you did then? Er, medium nights? What do you call them?’

Beryl opened her hands and spread them across the table. ‘Evenings of clairvoyance,’ she said in a singsong voice. ‘Yes, we put on quite a few and also ran a series of taster afternoons.’

I wrote that down in my notepad. ‘Which were what?’

‘I call them old skool,’ said David and laughed.

‘He means they’re old-fashioned,’ Beryl said gently. ‘There’s a few of us that have practical skills – reading the tea leaves; auras; dream interpretation, that sort of thing. A young lady, Tanith, from the neighbouring village is one of them Witchens.’

David leant in to correct his mother. ‘She’s a Wiccan.’

‘She does a lovely tarot, don’t she, David?’

Bennett Junior nodded. ‘Very accurate.’

‘So we got together and ran about ten of those. One a month. With volunteers selling tea and cake. And we hosted evenings. All the funds came through suggested donations.’

‘And you raised that much?’ I asked, doing a rough calculation in my head.

‘Some of the recently bereaved can be very grateful when they make contact with loved ones on the other side. It helps, you know.’

I wrote that down in my notepad and then flipped it shut so I could take a gulp of tea. ‘So, do you have practical skills, David?’ I turned slightly to him. He was on my left side facing the door.

‘Numerology,’ he said brightly. ‘Numbers. And astrology.’

‘Right,’ I said, searching for the right word to express limp engagement. ‘Interesting.’ It sounded so disingenuous I asked Beryl quickly, ‘And what about you, Mum? Do you have more skills? Other than clairvoyance of course?’

Beryl nestled into her chair and beamed. ‘Palms. Chiromancy, I like to call it. Always been able to do it. Even before I had the calling to clairvoyance. It’s just something I’ve grown up with.’ She chuckled. ‘I can see in your face that you’d like to have a go.’

‘Oh.’ She wasn’t that great a clairvoyant – I hadn’t thought about it. But the idea had a certain appeal. ‘What, now?’

‘Won’t take a moment, love.’ She patted the chair to her side. ‘Come and take a seat.’

I placed my teacup next to my notebook and swapped chairs. Beryl put her cup down and rubbed her hands. ‘They’re a bit cold, so ’scuse me.’ Then she picked up my right hand. ‘David, love, could you fetch my specs. They’re beside the cooker.’ David scurried over and came back with a small brown case. Beryl popped the glasses over her nose. She examined the skin of my palm and stroked a couple of fingers, then peered down at the left side of my hand.

After a minute she cleared her throat. The smile that hung upon her chocolate lips faded. ‘Were you very ill when you were young, dear?’

She looked over the tops of her glasses at my expression.

‘No,’ I said, blankly. ‘Not that I’m aware of.’

Beryl touched her throat then reached out and picked up the cup of tea. She swallowed hard and returned to my hand.

David was also scrutinising it, drawn in by the attention his mum was giving.

She pummelled the flesh beneath my little finger and grimaced.

‘What is it?’ I asked, trying to grin.

‘Mmm,’ she said slowly and pushed the glasses back up her nose. ‘Sorry to ask this, but you’re not adopted are you?’

I laughed. ‘Definitely not.’

David stood up and gazed over his mother’s shoulder at my palm.

‘I don’t think it’s coming through well today, love.’ Beryl’s voice had risen.

‘Blimey,’ said David. ‘That’s a short one.’

‘What is?’ I asked too quickly.

Beryl sent him a warning look but he didn’t catch it.

He leant forwards and swayed on the balls of his feet. ‘By my reckoning …’ he started to say.

‘David!’ Beryl nudged him sharply in the ribs.

David’s brain didn’t connect with his mouth in time. ‘By my reckoning,’ he said in mock horror, ‘you’re already dead!’

He laughed heartily.

I didn’t.

I had become very cold.

Beryl sucked her teeth in annoyance. ‘David, sit down. Now don’t you go scaring people like that. Honestly,’ she said wearily. The bags under her eyes had darkened into swollen crescents of lilac. At that moment she did look very old indeed. ‘Typical man. No tact. Just like his dad.’ She sighed and pushed my hand away. ‘I’m sorry, love,’ she said, sitting back into her chair. ‘Can’t do any more. I’m not feeling too good.’

‘Oh dear,’ I said, returning to my previous seat. ‘Sorry. I hope it wasn’t anything that I …’

She didn’t reply to me. Instead she addressed the next instruction to her son. ‘Go fetch my pills please, love. They’re on the bedside table nearest the door.’

David got to his feet immediately and dashed out the kitchen.

Beryl was now the colour of ashes. Her make-up seemed only to be resting on top of her skin; beneath the foundation little muscles were flicking and flexing, as if an electric current was running through them.

‘Would you like a glass of water?’ I asked gently.

She rasped a reply I couldn’t understand. Then her eyes fixed on me. All the rigidity and animation seemed to leave her body at the same moment and she slumped back in the chair. For a second her neck went slack and rolled backwards.

I stood up, worried yet completely unsure of what to do. Something was happening to the poor woman but I couldn’t tell what. I simply stood there and watched with growing alarm as Beryl’s neck moved upwards and forwards, pulled by an invisible thread. Her head slowly followed. And what a strange sight that was – the luscious brown hair, obviously a wig, slipped off, revealing a thinning layer of feathery white tufts. When I saw her eyes I very nearly screamed. They had rolled round so that all that poked through the hooded lids were the bloodshot whites. And then the shaking started. Not a sideways motion but a juddering up and down, quick sharp micro-moves.

A horrible creak was coming from inside her mouth. Her jaw slackened and then fell open, making a grating noise, then slowly it appeared to unhinge and drop lower than I ever thought possible without splintering bone.

Despite Beryl’s agonised movements I could do nothing but stare. A terrible paralysis had crept over me. I watched her kindly face disappear into a barely recognisable combination of features in seizure.

Her hands began to scratch at the table and the whites of her eyes fixed on my face, as if something beyond them perceived me.

Beryl’s frame jerked backwards, the upper half of her body shaking uncontrollably.

A gurgling came up from her throat. I could see she was struggling to breathe.

‘Oh God,’ I said, coming to my senses at last, and rushed round to Beryl’s side. ‘What can I do? Beryl? Mrs Bennett, are you okay?’

And then I heard it, coming up through her windpipe: a kind of wheeze; a low-pitched primal scream. Something like, ‘Ashhhh bitten.’ I couldn’t be sure: the word was wrenched out of her, fuzzy with sibilance and choked with phlegm.

Beryl convulsed. Her hand flew to her neck. The body heaved. She coughed once, twice, then gagged. As her face surged forwards to the table, her lips opened wider yet.

I gasped with shock and repulsion as I observed a black moth fly out of her mouth.

‘Shit.’ I was jittering now, backing away from her.

The kitchen door was flung open just as Beryl’s body lolled forwards and she collapsed onto the table.

‘Jesus Christ,’ I said to her son, pointing to his mother’s prone form. ‘I think she’s having a fit.’

David rushed over and lifted his mother’s sagging shoulders back onto the seat.

‘Get some water,’ he barked.

I tore over to the tap and brought back a beaker.

Beryl was coming round.

Her irises had returned to her eyes but there was a dizzy circling going on in them.

David took the water and held it to his mother’s lips. ‘Come on, Mum. Take them down.’ With his fingers he popped a little yellow pill on her tongue.

‘What happened?’ I asked him, looking on anxiously at his mum. ‘Is she going to be all right?’

‘She’ll be fine in a bit,’ he said. ‘Look, if you don’t mind, I’d like to get her onto the sofa for a rest.’

‘Yes of course,’ I said and gestured to Beryl’s arms. ‘Shall I take this side?’

‘No,’ he snapped, knocking my hand away from his mother. ‘Don’t touch her. I’ve got everything under control.’

‘Right,’ I stammered, feeling disproportionately guilty.

‘Please leave, Ms Asquith. You can see yourself out I presume?’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said and gathered up my things super quick. ‘I’ve got everything that I need to put the article to bed. Thank you for your time.’ David Bennett had already picked his mother up and carried her from the room.

I was opening the front door when I heard Beryl call out weakly. ‘Take care, Ms Asquith. Be sure to.’