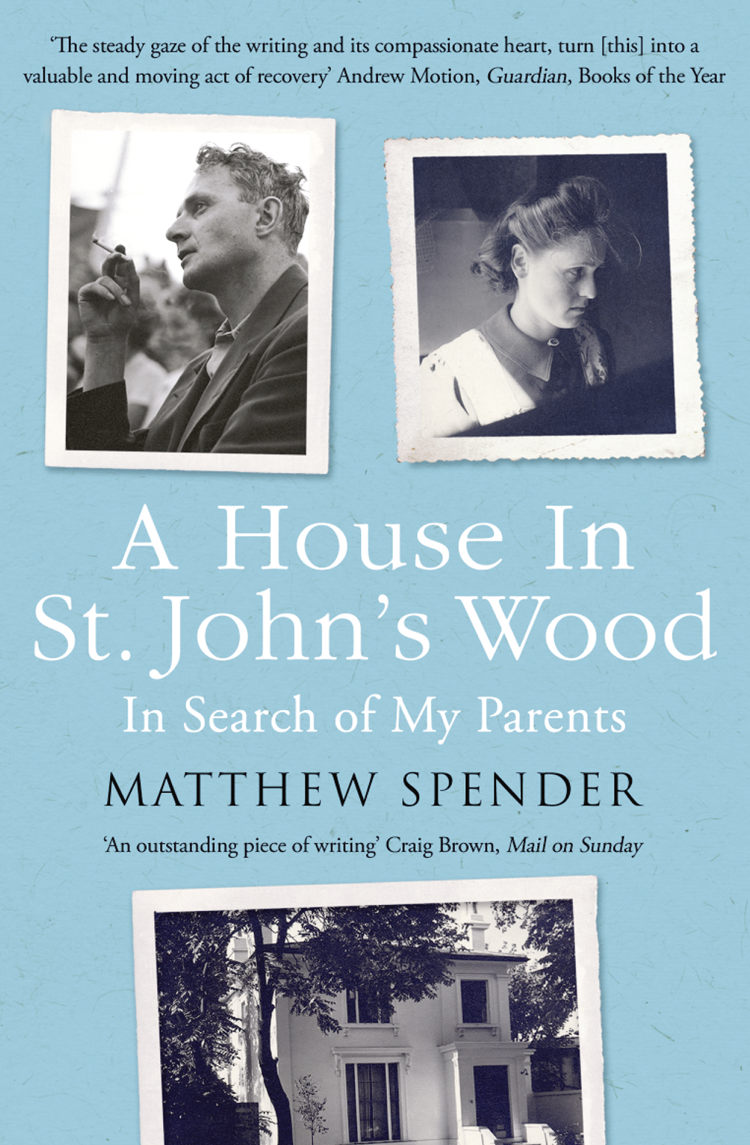

A House in St John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents

My father and me in 1957.

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Matthew Spender 2015

Matthew Spender asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover images © Lizzie and Matthew Spender Collection (photographs), except for (top left) by W. Eugene Smith/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; Shutterstock.com (background texture and picture frames)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008132064

Ebook Edition © August 2015 ISBN: 9780008132071

Version: 2016-05-24

Dedication

To my grandchildren: Cleopatra, Aeneas, Ondina and Marlon

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Natasha’s Last Wishes

Chapter 1: A worldly failure

Chapter 2: Without guilt

Chapter 3: Suicide or romanticism

Chapter 4: A sly Shelley

Chapter 5: Mutual renaissance

Chapter 6: Fires all over Europe

Chapter 7: The purity was hers

Chapter 8: America is not a cause

Chapter 9: Your sins of weakness

Chapter 10: Don’t you ever tell a lie?

Chapter 11: Dreaming one’s way through life

Chapter 12: Scandalous gossip

Chapter 13: The irresistible historic mixed grill

Chapter 14: The kindest face

Chapter 15: A strong invisible relationship

Chapter 16: Barrenness and desolation

Chapter 17: Too ambivalent

Chapter 18: You’re unique

Chapter 19: Without banquets

Chapter 20: Over-privileged?

Chapter 21: Might just as well be married

Chapter 22: A nice little niche

Chapter 23: Trust

Chapter 24: Killing the women we love

Chapter 25: Your father will survive

Chapter 26: Romantic friendships before all

Chapter 27: The right to speak

Chapter 28: Guileless and yet obsessed

Picture Credits

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

NATASHA’S LAST WISHES

MY MOTHER DIED on 21 October 2010, at eleven in the morning, in her bedroom on the top floor of 15 Loudoun Road, the rented house in St John’s Wood where she’d lived for the previous sixty-nine years. I heard the news on my cellphone driving along a back road in Tuscany. I rushed home, collected my passport and flew to London, where I arrived at about seven in the evening.

The house had been neglected since my father’s death in 1995. A large crack ran down the external wall to the right of the front door. Squirrels nested in the roof next to the water-tank, and they’d reopen their hole every time we patched it up. I’d offered to make major repairs on condition that I’d be reimbursed after her death, but the lawyer told me, ‘It won’t happen. Buy her an umbrella.’

Downstairs in my father’s study, my mother’s attempt to organize his papers had replaced the creative untidiness of work in progress with the sepulchral untidiness of boxes ready to be taken to an archive. In the music room her Steinway was shrouded and the scores were shelved. In her last years she’d actually forgotten how to play. The back door from the kitchen to the garden, squeezed by subsidence, had been planed so many times to make it fit the frame that it was no longer a rectangle. The house was a tomb long before her death added an aura of absence to the surreptitious creak of decay.

Her live-in minder had packed a rucksack and was waiting with her boyfriend in the hall. As I kissed her cheek, I smelled the excitement of a witness who’d seen someone die. I wondered if the experience was as thrilling as observing a birth.

My wife was waiting for me in the piano room. We phoned for the undertaker. Then I went upstairs to say my goodbyes. I took a sketch-pad with me to make some drawings of my mother as she lay there. I’d done the same with my father and it had been a fascinating experience, but this time it didn’t work. The drawings came out angrier and angrier. Was this my feeling, or hers? She herself just looked exhausted. The anger was in the drawings.

By her bedside lamp lay a curl of papers. In a desultory way I straightened them out. They were documents designed to exclude me from my father’s literary inheritance. A covering letter showed that she’d arranged to sign these in front of the lawyer a few days later.

She’d been talking about this for years and I’d always told her she should do whatever she thought best. Would she or wouldn’t she? There was an element of sadism in my detachment. In the background lay a battlefield. She knew I disagreed with her interpretation of my father’s life. To her, he’d always been a pillar of integrity, and anyone who questioned this was despicable. I agreed about his integrity, but everything else about my father’s life made me want to qualify her pure idea of him with the confusion of reality.

I’d always expected her to change her mind about cutting me off, but here we were. Dutifully, I took the documents to the lawyer the following day. Were we obliged to honour her wishes? The lawyer flipped through the papers and asked, ‘Where’s the signature?’ I said that she’d planned to sign them in his presence – let’s see – tomorrow afternoon. ‘A lot of old ladies leave things just a bit too late,’ he said. And casually he dropped them in the trash.

All other aspects of her Will were fine. She’d left everything to my sister Lizzie and myself. She hadn’t created a foundation dedicated to protecting her husband from my interpretation of his life. The lawyer added soothingly that, as we were our parents’ sole heirs, the literary executorship was of minor importance. So I calmed down.

It took us ten days to organize the funeral. Lizzie had just flown from London to Sydney and she needed time to recover before she’d fly back.

While I waited, I sat alone in the piano room listening to the shuffling of the masonry. I looked through the boxes next door but they contained nothing that interested me. Then I tried the door of the tiny room downstairs where my father used to store all the papers that he felt he couldn’t throw away.

It was still untidy, but no longer the impenetrable chaos it had been during my father’s lifetime. The correspondence had been sorted into slim files stored in alphabetical order. Among them I found two packages marked in my mother’s handwriting, ‘to be destroyed without opening after my death’. One was shut with a strip of Sellotape. The other had also been shut, but somebody had sliced it open. I took them upstairs to the piano room. After an hour of dithering, I began to read the contents of the open file. They were letters from Raymond Chandler to Mum. After reading two or three, I realized they were passionate love letters.

I rang the lawyer and asked if we had to obey her wishes. ‘No,’ he said. ‘She had the right to destroy her property, you don’t. You could, but if I were you I wouldn’t.’

Raymond Chandler’s supposed passion for my mother had become one of the great ‘causes’ of her old age. A biographer had come across some evidence in Chandler’s archive and he believed that an affair had actually taken place. My mother went wild. Friends were asked to intervene. She who was so frugal spent hundreds of pounds on solicitors. In the end, the biographer gave in and the evidence was written up as a fantasy, but the letters I was reading in the piano room showed that their friendship hadn’t been quite as limpid as she’d always maintained.

While my mother was alive, I’d accepted her assertion that she was in charge of the past. She was the keeper of the flame, my father’s life belonged to her. She was obsessed by the thought that bad books would be written about Dad and lurk on library shelves waiting to ambush the innocent reader. Now, all those neat files would enter an archive. Wasn’t it my duty to present my parents’ lives in the best possible light, before hostile biographers started plundering them?

That’s what I thought, but a month after I’d started writing, my mother came to me in a dream. She was furious. ‘What makes you think you can write a book about us? For instance, what do you know about—’ and here she mentioned someone I’d never heard of. I mumbled an answer. ‘There you are,’ she said triumphantly. I explained hesitantly that if a book is well written, whether or not it’s the actual truth, it acquires a truth of its own.

In the background, my father sniggered. She asked, ‘And what are you laughing at?’ ‘Well,’ he murmured apologetically, ‘it only goes to show what he thinks of literature.’ I said that they were both dead, so they couldn’t be offended. The dead have no feelings, I said. My father stopped laughing and I woke up.

I lay there thinking how curious it was that they should behave in character, even in a dream. When they were alive, if my mother was determined about something, my father always backed down. But I wasn’t sure I understood what he meant about my thoughts on literature.

My father thought that literature should tell the truth. His poems were always built upon specific moments when life had been revealed to him in all its simplicity and nakedness. The poem had to bear witness to that vision and transcend the mere sentences of which it was made. The idea of truth was very important to him. In politics, which occupied a great deal of my father’s attention, ‘the truth’ meant one must never tell lies in the name of a higher cause, or sacrifice the rights of an individual in the name of the collective good.

These truths are complicated. Both, I think, involve ideas about England. But since I left England forty-five years ago, and since I refused to discuss any aspect of my parents’ lives with them while they were alive, what chance do I have of chasing the truth now?

At this point a memory comes back to me of my father’s study while he lived: the books and articles finished at the last possible minute, stuck together with tape and paperclips. The galley proofs, the glossy sparkle of the published version. To write a book is to embark on a quest, and if in this instance I’ve made mine more difficult, so much the better.

1

A WORLDLY FAILURE

IT WAS W. H. Auden who taught me about adjectives. He stayed with us whenever he came to England. I was nine years old. Scene: 15 Loudoun Road, my parents’ house in St John’s Wood, eight-thirty in the morning. I was late for school. Wystan, with an air of having already been up for hours, was smoking at the breakfast table, bored or thoughtful, looking out of the window at the tangled ferns of the basement area. Mum and Dad were still in bed, in their bedroom with a large dressing-table on which lurked strange hairbrushes sold recently to Dad by a sadistic hairdresser who had persuaded him he was losing his hair.

I was in a panic over a test due that morning on what an adjective was.

Wystan looked surprised.

‘An adjective is any word that qualifies a noun,’ he said.

‘I know how to say that,’ I said. ‘But I don’t understand what it means.’

He looked around the table, discarded the cereals and found among the debris of the night before a bottle of wine. One object more memorable than the others.

‘Ah … you could say, the good wine,’ he said firmly. ‘Its goodness qualifies the wine.’ Then he thought for a moment, peering at the bottle. ‘The wine was good,’ he said, correcting himself; and added in a tragic voice, ‘now all we have left is an empty bottle.’

That summer, my sister and I had been abandoned on an island off the coast of Wales. I’d liked it. Lots of puffins, a few cormorants and numerous placid sheep. On top of the hill in the middle of this island were three grass tombs of long-dead Vikings, and Bardsey Island had left me with an obsession with barrow-wights and the sinister mystery of Norse ghost stories. Hearing about this later that year, Wystan sent me from New York the Tolkien trilogy, The Lord of the Rings. I read it straight through.

Auden used to say that he knew where every detail of this trilogy came from and one day he’d write about it. Dad tried it once but he found Tolkien tremendously boring.

Once, Wystan and I wrote Tolkienish poems together, still over breakfast but a few years after the adjectives. I collected them and copied them into a notebook that I decorated with a heraldic crest ‘with whiskers’, as that kind of shading was called at school. Here are a couple of verses:

God knows what kings and lords,

Had their realms on these downs of chalk,

And now guard their bountiful hoards,

One night you may see them walk.

They walk with creaks and groans

Cloaks fluttering as they go by,

They ride on enormous roans

Which block out the stars and the sky.

Lines two and four of each verse are Auden’s. ‘Can I use them?’ ‘Of course.’ I got the impression that words could be seized out of the air and given generously from one person to another.

My frequent readings of The Lord of the Rings always featured Wystan in there somewhere. The kind but didactic Wizard. In this earliest phase of knowing Wystan I intuitively grasped his own self-image as a young man, which was that of ‘Uncle Wiz’, an eccentric Victorian vicar with a bee in his bonnet about the Apocrypha. He didn’t want to be taken seriously every inch of the way. He liked to pontificate, but he also wanted be teased about it in return. It was part of his longing for universal love, a very strong need he had.

Wystan knew a great deal about our family. There’s a story of him running round and round the aspidistra at our house in Hampstead when he was a little boy. He was my uncle Michael’s friend at Gresham’s, Holt, the school they both attended. They were two years older than Stephen, who only met Wystan when they were undergraduates at Oxford.

At Gresham’s, Michael and Wystan had sat through a memorable occasion when Harold Spender came down to give the boys a pep talk. My grandfather read the parable of the Prodigal Son, and when he came to the words, ‘But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him,’ Harold looked lovingly at his son Michael, perched at the keyboard of the organ in full view. I think Wystan must have remembered this story because, without intending to, Harold had for a moment become ‘camp’. Anyway, it was Wystan’s story. My father was at the under-school of Gresham’s at the time so he did not witness this memorable scene.

Having thus embarrassed his eldest son, my grandfather continued with a stirring sermon along the lines of ‘On, and always on!’ (It’s the title of the last chapter of his autobiography.) There was a boy-scout element to Harold and he wanted to inspire these youngsters with manliness. But it did not go down well. It was just after the First World War during which many former pupils had lost their lives. Their names glowed freshly on the oak panels behind him.

‘You killed him, my dear,’ said Wystan over supper at Loudoun Road, around the time when we wrote the Tolkien poems together. And when Dad started laughing, he said firmly, ‘You killed him by ignoring him.’ Dad stopped laughing and looked annoyed. He’d never believed Auden’s theory that sickness, or even death, comes from damage to the psyche: that heart disease comes from an inability to love, that cancer comes from ‘foiled creative fire’. He called this aspect of Auden’s imagination ‘medieval’. In this case Wystan – smiling at Dad with benign condescension – was saying that the young Spender boys had killed their father with snubs.

I don’t know why my father had such difficulties with his parents, but it might have had something to do with the anger of young people towards the older generation, which they held collectively responsible for the disaster of the First World War. How could anyone believe in the world of ‘clean thoughts in clean bodies’ after that? Stephen hated his father. He thought he was a failure. He was only seventeen years old when Harold died, so his relationship was frozen in an adolescent image where Harold was the hieratic statue that had to be toppled from its pedestal. If ‘killing the father’ is an essential part of growing up, Stephen did his early.

It was easy to mock this man who could never earn enough money to keep his family going and who yearned for unattainable positions of power. But the bitterness with which Stephen writes in his novels and his poems about ‘failure’ meant that, at some level, he subscribed to Harold’s romantic notion of life as a series of peaks, of challenges, of high aspirations and magnificent achievements. ‘Failure’ was Stephen’s way of defeating his father, but it also kept alive Harold’s scale of values.

When Stephen was twelve, Harold stood as a Liberal candidate in a general election. My father remembered being hauled around Bath in a pony-carriage with his two brothers, each with a placard round his neck saying ‘Vote for Daddy’. Harold lost, and the effect on Michael and Stephen was traumatic. Michael said: ‘When they are very young, the children of a public man worship their father for being famous – a kind of god: but it’s extraordinary how soon they get to realize it if he’s a public failure.’ Michael developed a stammer. He decided that his father was ‘inefficient’, which in his eyes was the worst thing a man could be. Stephen, instead, just couldn’t stop crying. It confirmed his suspicion that his father was a windbag whose exhortations of ‘on and ever on’ were meaningless.

Harold Spender’s wife, my grandmother Violet Schuster, came from a successful Jewish family that had emigrated from Germany to England in the 1860s. At the time of their marriage, the Schusters established a trust for Violet and her children – a long document camouflaging the fact that Harold wasn’t allowed to touch it.

Violet was a delicate woman who gave birth to four children in four years, one after the other. She died in 1921, at home, on the kitchen table, after an operation to remedy complications deriving from a hysterectomy. For years she’d struggled with a condition that could not be named. Her death was a great shock. Until then she had been able to run the house (peremptorily) and accompany her husband on his frequent trips to Europe and America.

My father’s dominant memory of her was of her complaints. Too much noise was coming from the children’s room; they’d given her a headache. Because the details of her state of health were never discussed, he probably assumed that his mother was more neurotic than was the case. ‘Hysteria’, in Aristotelian terms, means blood boiling in the womb, and I’m sure that my father’s incapacity, indeed terror, of anything resembling a woman’s lack of control over her body stemmed from an unhealed memory of his mother’s sufferings.

They all spent a fortnight in the Lake District during the First World War. Violet was in a bad state because of the death of her much loved brother in the trenches. The war was present even in this beautiful place. She noticed that Keswick had been emptied of its men, leaving behind only those who were working on the farms. She saw several Scottish soldiers on the train drinking desperately at the thought of having to go back to the front. ‘A thin match-boarding separates us all from some terrible thing dimly known.’

In spite of her dark state of mind, they enjoyed this moment of escape. It was one of the few times when they were together as a family. Stephen chased butterflies, Humphrey collected crystals that glittered on the paths leading up into the hills behind the farm. When it rained, slugs sailed down the paths like barges on the Thames. Michael bonded with Harold and learned how to row a skiff on Derwent Water. Harold also taught Michael about climbing, and gradually they formed a team from which the others were excluded. Harold was a great climber. His guide to the Pyrenees is still read. There’s even a recent translation into Catalan.

For the rest of his life, Stephen wrote and rewrote his memories of Skelgill Farm. A key moment took place when he overheard Harold reading Wordsworth’s Prelude to Violet as they rested in deckchairs looking at the sunset. They were in deepest Wordsworth country; it was a predictable book to choose. Stephen, aged eight, understood ‘Wordsworth’ or ‘Worldsworth’ to have something to do with his father’s metaphorical symbolism: the world was a word, and the word had worth – was valuable.

Stephen asked his mother why Wordsworth was a poet, and what a poet was. She said:

Wordsworth was a man who, when he was a child, ran through the countryside and felt himself to be a living part of it, as though the mountains were his mother, his own body before he was born. And when, in later life, while he was still young, he came back from many journeys to the lakes, he felt all those memories, which were one with the scenery, surge through his arms and legs and his whole body on his walks here, and come out through his fingers that held a pen, as words that were his poems.

After Violet’s death in December 1921, Harold went into a decline. The finances of the household were now controlled by his mother-in-law, Hilda Schuster, with whom Stephen formed a conspiratorial relationship based on books and trips to the theatre and long conversations of a kind that Harold’s self-righteousness precluded. Stephen’s hatred of his father could have derived from a subconscious conviction that Harold was responsible for his wife’s death, but in the many texts my father left, he stresses only the absurdity of his father’s grief. ‘I am a broken man,’ said Harold over lunch, blinking at his children. ‘You are all that your poor old father has left.’

In his autobiography, my father writes: ‘it is no exaggeration to say that at the end his unreality terrified me’. In 1940, writing his novel The Backward Son, Stephen returned to his father’s reaction to his wife’s death. Harold’s lack of reality has become a caricature. ‘He saw what he had never seen – that he was a fool, and that she had a touch of genius. “The divine fire of Parnassus breathed on her,” he thought, automatically trying to make this thought unreal.’ (Harold published Violet’s poems soon after she died, but he never claimed that she was an unrecognized genius.) ‘It was she, he now realised, who had saved him; it was she who had made him, in spite of everything – he could grasp it now – a worldly failure. For he knew now that he would never succeed, he would never be in the Cabinet, he would lose his seat in the House, he would be despised.’ (In this novel Harold is an MP, a role he never achieved in life.) ‘His one saving grace which he could secretly cling to for the rest of his life was his sense of failure.’