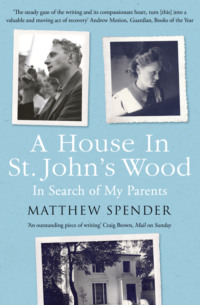

A House in St John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents

Harry Giese was mundane; but Stephen always hoped that one day a working-class crim would produce a poem from his pocket, ‘magical with the mystery of the lights and silver balls of amusement arcades, or smouldering with the passion which chooses a different bed-mate from the pavements every night’.

After Harry, there was a seventeen-year-old Russian stateless boy whom Stephen calls in his letters Georg 101. I have no idea what the 101 stands for, but Georg might have been connected with the school for workers in the Karl-Marx suburb of Berlin where my father taught English for a while.

In 1932 there was a more serious adventure, though it sprang from a ridiculous beginning.

At this point Stephen had been living in Berlin for several months every year next door to Christopher, who was immersed in the material that later became his Berlin stories. But Stephen also kept his presence alive in London, which he visited frequently. Christopher, on one of his rare trips back to England, found that Stephen had been dining out on their Berlin adventures. He panicked. His material was being appropriated. He solemnly told Stephen that Berlin was no longer large enough to accommodate the two of them and their friendship was at an end. Instead of telling Christopher, Don’t be silly, my father was so upset that he ran off to Barcelona to save a German boy who was miserable. They’d never met. Someone at a party in London told Stephen he should go, so off he went.

The boy in question, Hellmut Schroeder, turned out to be a narcissistic former waiter from one of the main hotels in Berlin. He was convinced that he’d been victimized by all the people who’d befriended him. ‘It’s as though all those crowds of people in the square here, and in Berlin, and in the hotels where I have waited, had slimed across me, leaving their tracks like snails.’ The name ‘Hellmut’ means ‘Light-strength’, but in letters written back to Christopher in Berlin, Stephen said he should really be called ‘Dunkelmut’, or ‘Dark-strength’, such was the boy’s melancholia. He’d even become unhappy if Stephen told him he was looking happier today than yesterday.

‘I think that all he needs is to be liked,’ Stephen wrote to Virginia Woolf, ‘so as I like him extremely I shall stay here.’ He preferred the days that were ‘domestic’. Hellmut became gradually less sulky, indeed he attempted to respond to Stephen’s kindness. They began vaguely looking for somewhere to live. House-hunting reassured Hellmut, because it suggested permanence. Yet there was something odd about Stephen’s affection, something that Hellmut felt he had to challenge. ‘We were very affectionate all of yesterday. Yet H. questioned me again, because he is always anxious to prove that I am fond of him, but that my fondness is unlike that of the hundreds of people who have been physically attracted to him.’

Stephen gradually became aware that, in spite of his efforts, he could not become close to Hellmut. He blamed himself. In a rare passage of analysis in his diary, he gives way to self-loathing. ‘I have the stupidity & the intelligence, the openness & the tiresome subtlety of the educated savage.’ There’s a lot of Englishness packed into that one sentence, or at least the Englishness of a certain class and education of the time: ‘The central regret of the person who is intellectual & who realizes that intellectualism has no absolute moral worth is that he is dependent for this realization on his intellect. Therefore he wishes to prostrate himself to a class of people who are unintellectual.’

My father thought that the working class possessed a secret which had been eradicated from the bourgeoisie by education. The working class, having been exploited for the benefit of the bourgeoisie ever since the Industrial Revolution, had managed to keep alive their feelings. Their lack of sexual inhibition was a gift; and sex was the highest form of communication between people. Sex stood at the core of universal brotherhood. Though at an intellectual level he would acknowledge that women also faced the challenge of bringing their sexuality into line with other forms of freedom, to him the sexuality of men was more romantic, more moving. The breadlines consisted of queues of men; women were hardly visible.

In Barcelona, they tried to create a social life. Then Hellmut began to have affairs with other men. At first Stephen was upset, then he was merely bored. He realized he’d been stupid to think he could save him. ‘Hellmut is a nice person, very hysterical, beautiful, uninteresting, sensation-mongering, and second-rate who has the incredibly petit-bourgeois mentality of most German homosexuals.’ Stephen thought that Hellmut was jealous of him, ‘because I am not completely petty and because I live very happily in a world that he cannot reach’.

Enter unexpectedly an alcoholic American writer called Kirk, sent by a friend of Isherwood’s in Berlin. Where Hellmut was difficult, Kirk was impossible. What’s more, they were jealous of each other. ‘Hellmut is a homosexual of the “major unknown authors of our time” type, so that the arrival of Kirk led to all sorts of absurd dramas being performed.’ Somehow the story fumbled its way to a conclusion without any casualties. Kirk eventually went off to Ibiza and Stephen sent Hellmut back to Berlin.

Because it dealt with homosexual acts, it was inevitable that Stephen’s brave novel The Temple would be turned down. On one of these occasions – and there were many – Stephen wrote a revealing letter to his grandmother, who’d become involved in trying to place the book: ‘To me the book has the significance of a vow that I made to my friends. I promised them that I would write absolutely directly about certain things, and I think it is right that I should fulfil my promise. I am writing and working and living for my own generation and, in that sense, being modern is a religion with me.’ The conventional life of the 1850s was dead, he wrote. ‘As regards sexual abnormality, I don’t think that, or any other of the startling symptoms of contemporary society that so shock the English reader, are nearly so important as people imagine. My feeling is that if one loves one’s fellow-beings, one cant be so very abnormal.’

He’s hinting, I think, that The Temple was in some way connected to the stories that Isherwood was writing at the time. If the comparison is worth making, then his novel is more explicit, perhaps more courageous than the ambiguous and undefined ‘Herr Issyvoo’ of the Berlin stories. Christopher read several versions of the book but, having once written a ferocious criticism of a novel by Stephen, he kept his comments to himself.

Deep down, my father must have known that The Temple would never be published. Quite apart from its sex scenes, it was also libellous. I suspect he sustained himself through five rewrites by the fantasy that one day it would come out, and the book would be denounced to the magistrates and banned, and he himself put on trial for obscenity. At Oxford he’d met Radclyffe Hall, the author of the lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, and he’d invited her to speak to the English Society. She’d replied with a letter of touching bravery describing all her troubles with the magistrates, which were long and costly. Stephen also admired unconditionally D. H. Lawrence, whose Lady Chatterley’s Lover had also been banned. If he’d ever been arrested, he would have given a passionate speech in support of freedom of expression along the lines of the letter he’d sent to his grandmother.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги