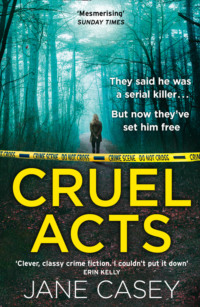

Cruel Acts

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Jane Casey 2019

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (forest and yellow tape)

Jane Casey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008149031

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008149055

Version: 2019-02-13

Dedication

For Sinéad and Liz, my wise women

Epigraph

The investigator should pursue all reasonable lines of enquiry, whether these point towards or away from the suspect.

Code of Practice for Investigators

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Jane Casey

About the Publisher

1

The house was dark. PC Sandra West stared up at it and sighed. The neighbours had called the police – she checked her watch – getting on for an hour earlier, to complain about the noise. What noise, the operator asked.

Screaming.

An argument?

More than likely. It’s not fair, the neighbour had said. Not at two in the morning. But what would you expect from people like that?

People like what?

A check on the address had told Sandra exactly what kind of people they were: argumentative drunks. She’d never been there before but other officers had, often, trying to persuade one or other of them to leave the house, to leave each other alone, for everyone’s sake. It was depressing how often she encountered couples who had no business being together but who insisted, through screaming rows and bruises and broken teeth, that they loved each other. Sandra was forty-six, single and likely to remain so, given her job (which was a passion-killer, never mind what they said about uniforms) and her looks (nothing special, her father had told her once). Generally, she didn’t mind. It was peaceful being on her own. She could do what she wanted, when she wanted.

Sandra had a look in the boot of the police car and found a stab vest. Slowly, fumbling, she hauled it around her and did it up. It was stiff and awkward, made to fit someone much taller than Sandra. Still, it was in the car for a reason. She walked up the path to the front door. Everything was quiet. Hushed.

Maybe one of them had taken the hint and left before the busies arrived. Sandra shone her torch over the window at the unhelpful curtains, then bent and looked through the letterbox. A dark hallway stretched back to the kitchen door. It was quiet and still.

A screaming argument that ended with everyone tucked up in bed an hour later? Not in Sandra’s experience. She planted her feet wide apart, knowing that she had enough bulk in her stab vest and overcoat to intimidate anyone who might need it. Then she rapped on the door with the end of her torch.

‘Police. Can you open the door, please?’

Silence.

She knocked again, louder, and checked her watch. God, nights were hard work. It was the boredom that wore you down, that and the creeping exhaustion that was difficult to ignore when you weren’t busy. She wasn’t usually single-crewed but some of her rota were off sick. She never got sick. It was something she took for granted – the colds and viruses and stomach bugs all passed her by. It made her wonder if everyone else was really sick or if they were faking, and whether she was stupid not to do the same. She tried to suppress a yawn with an effort that made her jaw creak. It was tempting to call it in as an LOB. Sandra smiled to herself. It wasn’t what they taught you at Hendon, but every police officer knew what it stood for: Load of Bollocks. Then she could get back into the car and go in search of refs. She hadn’t eaten for hours, her stomach hollow from it. Knowing her luck, she’d be about to bite into what passed for dinner and her radio would come to life.

The trouble was, there was a kid in the house. You couldn’t just walk away without finding out if the kid was safe. Not when there was a history of domestic violence and social services being involved. Chaotic was the word for it: not enough food in the house, patchy attendance at school, the boy needing clean clothes and haircuts and a good bath. How could you have a kid and not take responsibility for him? OK, Sandra’s parents had been short on hugs and they hadn’t had a lot of money to spend on her and her brothers, but they’d been reliable and she’d never once gone hungry. Nothing to complain about, even if she had complained at the time.

She bent down again and peered through the letterbox, moving the torch slowly across the narrow field of view this time. It cast stark shadows in the kitchen and across the stairs. But there was something … she squinted and changed the angle of the torch, trying to see. There, on the bottom step: light on metal. And again, two steps up. And again, three steps above that.

Knives. Kitchen knives.

They were stuck into the wood of the stairs, point first. All the way up, into the darkness at the top.

Sandra wasn’t an imaginative person but she had an overwhelming sense of fear all of a sudden, and she wasn’t sure if it was her own or someone else’s.

‘Hello? Can you hear me? Open the door, please, love. I need to check you’re all right.’

Silence.

Oh shit, Sandra thought, but not for her own sake, despite being scared at the thought of what might confront her inside the house. Oh shit something very bad has happened here. Oh shit we probably can’t make this one right. Oh shit we should have come out a lot sooner.

Oh shit.

She got on her radio and asked for back-up.

‘With you in two minutes,’ the dispatcher said, and Sandra thought about two minutes and how long that might be if you were scared, if you were dying. She’d asked for paramedics too, hoping they’d be needed.

The second police car came with two large constables, one of whom put the door in for her. His colleague went past him at speed, checking the rooms on the ground floor.

‘Clear.’

Sandra was halfway up the stairs, listening to her heart and every creak from the bare boards. The torch was slick in her hand.

‘Hello? Anyone here?’

The thunder of police boots on the steps behind her drowned out any sounds she might have heard. Bathroom: filthy in the jumping light from her torch, but no one hiding. A bedroom, piled high with rubbish and dirty clothes. No bed, but there was a pile of blankets on the floor, like a nest. A second bedroom was at the front of the house. It was marginally tidier than the other one, mainly because there was almost no furniture in it apart from a mattress on the floor. Shoes were lined up neatly in one corner and a collection of toiletries stood in another.

The woman was lying across the mattress, half hanging off the edge, a filthy blanket draped across her. Her head was thrown back. Dead, Sandra thought hopelessly, and made herself smile at the small boy who crouched beside the body.

‘Hello, you. We’re the police. Are you all right?’

He was small and dark, his hair hanging over his eyes. He blinked in the light, his eyes darting from her to the officer behind her. He wasn’t crying, and that was somehow worse than if he’d been sobbing. Sandra was bad at guessing children’s ages but she thought he could be eight or nine.

‘What’s your name?’

Instead of answering he huddled closer to the woman. He had pulled one bruised arm so it went around him. It reminded Sandra of an orphaned monkey clinging to a cuddly toy.

‘Can I come a bit closer? I need to check if this lady is all right.’

No reaction. He was staring past her at the officer behind her. She waved a hand behind her back. Give me some room.

‘Is this your mummy?’ she whispered.

A nod.

‘Is your daddy here?’

He mouthed a word. No. That was good news, Sandra thought.

‘Was he here earlier?’

Another nod.

Sandra inched forward. ‘Did you put that blanket over your mummy?’

‘Keep her warm.’ His voice was hoarse.

‘Good lad. Good idea. And you put something under her head.’

‘Coat.’

‘Brilliant. Can I just check to see if she’s all right?’ Sandra stretched out a gloved hand and touched the woman’s ankle. Her skin was blue in the light of the torch, and even through the latex her skin felt cold.

‘He hurt her.’

‘Who did, darling? Your dad?’

The boy blinked at her. After a long moment, he shook his head slowly, definitely. It would be someone else’s job to find out who had done it, Sandra thought, and was glad it wasn’t her responsibility. The closer she got to the woman on the mattress, the more she could see the damage he’d done to her. And the boy had watched the whole thing, she thought.

‘All right. We’ll help her, shall we?’

His huge, serious eyes were fixed on Sandra’s. She wasn’t usually sentimental, but a sob swelled up from deep in her chest and burst out of her mouth before she could stop it. She held out her arms. ‘Come here, little one.’

He shrank into himself, turning away from her towards his mother. Too much, too soon. She bit her lip. The sound of low voices came from the hall: the paramedics at long last.

‘I’m sorry, but you can’t stay here. We’ve got an ambulance for your mummy. We need to let the ambulance men look after her.’

‘I want to stay. I want to help.’

‘But you can’t.’

The boy gave a long, hostile hiss, a sound that made Sandra catch her breath. The paramedics crashed into the room, carrying their equipment, and shoved her out of the way. She leaned against the wall as they bent over the figure on the mattress. It was as if Sandra had come down with a sudden, terrible illness: her stomach churned and there was a foul taste in her mouth. A cramp caught at her guts but she couldn’t go, not in the filthy bathroom, not in what was going to be a crime scene. She clenched her teeth and prayed, and eventually the pain slackened. A greasy film of sweat coated her limbs. She lifted a hand to her head and let it fall again. What was wrong with her?

The boy had scrambled back when the paramedics crashed into the room. He crouched in the corner of the room among the shoes, those round solemn eyes taking everything in. Sandra watched him watching the men work on his mother’s body, and she shivered without knowing why.

2

It was a day like any other; it was a day like they all were inside. Time pulled that trick of dragging and passing too quickly and all that happened was that he was a day further into forever.

He sat on his own, in silence, because he’d been allocated a cell to himself. It was for his protection and because no one wanted to share with him. He wasn’t the only murderer on the wing – far from it – but he was notorious, all the same.

That wasn’t why no one wanted to share with him. His health wasn’t good, a cough rattling in his chest all night long. That was more of a problem than the killing, he thought. But he’d taken his share of abuse for the murders, all the same. No one liked his kind.

He shifted his weight in the cheap wooden-framed armchair, feeling it creak under him. He had never been a fat man but prison had pared away at his flesh, carving out the shadow of his bones on his face.

The room was fitted out like a cheap hostel – a rickety wardrobe, a small single bed, a desk against the wall. There were limp, yellow curtains at the window. At a glance you might not notice the bars across the same window, or the stainless steel sink, or the toilet that was behind a low partition. That was one good thing about being on his own. He’d shared cells before, when he was younger. You never got used to the smell of another man’s shit. Of all the smells in the prison – and there were many – that was the worst.

He picked up the envelope that he’d left lying on his desk. It was open. A screw would have read it before he ever saw it. That was standard. Small writing, black ink. He wasn’t used to seeing it: his name in that writing. He turned it over a couple of times. Nothing important in it or he’d never have seen it. But no one writes a letter without saying something, even if they don’t mean to say anything at all.

He ripped the envelope getting the letter out of it. The paper was flimsy, the words on the other side bleeding through. He wasn’t a great reader at the best of times. His eyes tracked down the centre of the page, the scrawl transforming itself into phrases here and there. Don’t forget we’re all trying … I know you can … easy for me to say … coming to see you … your appeal … lose heart … forget what happened … start again … have hope … your son.

‘Fuck you.’ It was a whisper, inaudible above the banging and shouting and echoing madness of a prison in the daytime. With a wince, he got to his feet and crossed to the toilet. He stood over it, tearing the letter in half and half again, ripping the paper until it was a handful of confetti. He dropped it into the bowl. He’d imagined the ink would run but it didn’t. The paper sat on the surface of the water, the black writing burning itself onto his retinas. He pissed on it in a stop-start trickling stream, annoyed by that as much as the way the paper stuck damply to the sides of the toilet. He flushed, and waited, and grimaced at the scattered, dancing fragments that remained in the water.

He had a whole life sentence stretching ahead of him but that wasn’t what made him bitter.

If by some miracle he got out, he would never be free.

3

The lift doors closed and I shut my eyes, then forced them open again. It took about half a minute to go from the ground floor to our office: thirty seconds wasn’t quite long enough for a cat nap, even for me. The weight of the box I was carrying pulled at the muscles in my shoulders and arms but that was fine; it distracted me from the wholly unpleasant sensation of mud-soaked boots and trouser legs. I didn’t need to glance in the lift’s mirror to see how bedraggled I was after a long night and a cold morning at a crime scene in a bleak, muddy yard. I only had to look to my left, where Detective Constable Georgia Shaw was hunched inside a coat that was as saturated as mine. Her usually immaculate fair hair hung around her face in tails. Like me, she was holding a heavy cardboard box filled with evidence bags and notes.

‘We drop this stuff off. We do our paperwork.’ I paused to cough: the chill of the night had sunk into my chest. ‘We finish up and we go home.’

Georgia nodded, not looking at me.

‘Nothing else. Home, hot baths, clean clothes, get some sleep.’

Another nod.

‘If anyone manages to track down Mick Forbes and he gets arrested we’ll have to come back to interview him.’ Mick Forbes, a scaffolder in his fifties, the chief and only suspect in the murder of his best friend, Sammy Clarke, who had been battered to death in the muddy yard where we’d spent the night.

Georgia sniffed.

‘So get some rest while you can.’

‘OK.’ Her voice was a whisper.

The lift doors opened and I strode out, trying to look as if it was normal for my feet to squelch as I walked through the double-doors into the office. Head high, Maeve.

A quick scan of the room was reassuring: a handful of colleagues, mostly concentrating on their work or on the phone. A few raised eyebrows greeted me. An actual laugh came from Liv Bowen, my best friend on the murder investigation team, who bit her lip and dragged her face into a serious expression when I glowered at her. But for a brief moment, I allowed myself to feel relieved. I’d got away with it this time. I’d rush through the paperwork and then escape, unseen by—

DCI Una Burt opened the door of her office. ‘Maeve? In here. Now.’

I stopped, caught in the no man’s land between her door and my desk. Common sense dictated I should put the box down rather than carrying it into her office, but that meant leaving my evidence unattended. ‘Ma’am, I’ll be with you in a minute—’

‘Right now.’ The edge in her voice was serrated with irritation and something more unsettling. The box could come with me, I decided, and trudged through the desks to Burt’s office.

My first impression was that it was full of people. My second was that I would rather have been just about anywhere else at that moment, for a number of reasons. The pathologist Dr Early sat in a chair by the desk, tapping her fingers on a cardboard folder that was on her knee. She was young and thin and intense, rarely smiling – which I suppose wasn’t all that surprising, given her job. Today she looked grimmer than usual. Standing beside her, to my complete surprise, was a man who was tall, silver-haired and catch-your-breath handsome. My actual boss, although he was currently supposed to be on leave: Superintendent Charles Godley.

‘Sir.’

‘Maeve.’ He smiled at me with genuine warmth as I put the box down at my feet. ‘You look as if you had an interesting night.’

‘Not the first time she’s heard that. But I’ll give you this, Kerrigan, you don’t usually look as if you spent the night in a sewer.’ The inevitable drawl came from the windowsill where a dark-suited man lounged, his arms folded, his legs stretched out in front of him so they took up most of the room. Detective Inspector Josh Derwent, the very person I had been hoping to avoid. I could feel his eyes on me but I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of reacting. Instead I smiled back at Godley.

‘It wasn’t the most pleasant crime scene, but I’ll live. It’s good to see you, sir.’

‘You too.’

‘Are you coming back to us?’ I had sounded over-enthusiastic, I thought, and felt the heat rising to my face. Una Burt wouldn’t like it if I was too keen to see Godley return. She had only been a caretaker, though, standing in for him while he was away on leave.

‘Not quite. Not yet.’ The smile faded from his face. ‘I’m here for another reason. I’ve got a job for you.’

‘For me?’

‘For you and Josh.’ Una bustled around to sit behind her desk, pausing until Derwent moved his feet out of her way. She sat down, pulling her chair in and leaning her elbows on the desk – the desk she had inherited from Godley. He was much too polite to react, although I knew he would have recognised it as her marking her territory. Currently, he was a visitor in her office and she wanted him to know it.

‘What sort of job?’ I asked, wary.

‘Leo Stone,’ Godley said. ‘Our latest miscarriage of justice.’

I frowned, trying to place the name. ‘I don’t think I know—’

‘Yeah, you do.’ Derwent’s voice was soft. ‘The White Knight.’

That sounded more familiar to me. Before I’d run the reference to earth, though, Godley snapped, ‘I don’t like that name. I don’t like glamorising murder. We’re not tabloid journalists so there’s no need to use their language.’

Derwent shrugged, not noticeably abashed. Before he could say something unforgivable and career-threatening, I spoke up.

‘You said a miscarriage of justice.’ I didn’t know why I was distracting Godley from Derwent. If the situation were reversed he would sit back and enjoy my discomfort. ‘What’s happened?’

‘He was convicted last year, in October. He’s been in prison for thirteen months now. One of the jurors in his trial has spent that time writing a book about the experience, and self-published it without running it past a lawyer. In it, he happens to mention how he and another juror looked up Stone on the internet, against the judge’s specific instructions, during the trial.’ Anger made Godley’s voice clipped, the words snapped off at the end. ‘They discovered Stone’s previous convictions for violence and told all the other jurors about it.’

‘I think my favourite line is, “We left the court to discuss the evidence we’d heard, but it was just a pretence. We had already decided he was guilty, because of what we’d found out for ourselves.”’ Burt leaned back in her chair. ‘Exactly what you don’t want a jury to say. But instead of making his fortune selling his book, he’s earned himself a two-month sentence for contempt of court.’

‘So Stone’s appealing.’ It wasn’t a question: there wasn’t a defence lawyer in the world who would let an opportunity like that slip through their fingers.

‘He is. At the end of this week. And the appeal will be granted,’ Godley said.

‘Right.’ Lack of sleep was making my head feel woolly. ‘Well, there’ll be a retrial. The problem was with the jury, not the evidence.’

‘There should be a retrial. But that’s the issue I have.’ Godley looked at me, his eyes even bluer than I’d remembered. ‘What do you know about the case?’

‘A little. Not much more than I read in the papers.’ I tried to remember the details I’d gleaned. ‘They called him the White Knight because he seemed to be rescuing his victims. He kidnapped them and killed them, either immediately or later. By the time we found the bodies they were too decomposed to tell us much about what he’d done.’