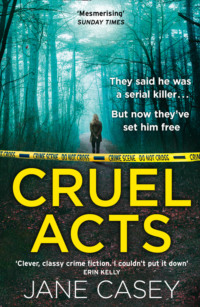

Cruel Acts

He nodded. ‘We only found two bodies but we’re fairly sure there’s at least one more victim. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more out there. He was a nasty piece of work. He was abusive in his relationships, he had convictions for fraud, burglary and theft, and he had a lengthy history of violence towards strangers, as the jury found out.’

‘When is he supposed to have started killing?’ I asked.

‘He got out of prison three years ago after serving five years for burglary. The first murder was a month later – a woman named Sara Grey. It was opportunist. Impulsive. I don’t believe he planned it particularly well but it worked so he tried it again.’ Godley folded his arms. ‘Don’t be misled by the nickname. He was a murderer, plain and simple, but they had to try and make him into something more exciting. They twisted the facts because they wanted to sell newspapers, not because it was true. He saw his opportunity to kidnap women and he took advantage of that. Three women disappeared in similar circumstances, but he was only charged with killing Sara Grey and Willa Howard. And he was convicted.’

‘OK.’ I was trying to read Godley’s expression. ‘But why does that involve us? It was Paul Whitlock’s team who investigated the killings, wasn’t it?’

‘It was, and he did a good job. But Glen Hanshaw was the pathologist who did the post-mortems.’

‘Oh.’ I didn’t need to say any more. I understood the problem now. Glen Hanshaw had been a good friend of Godley’s. He had clung on to his job despite the ravages of cancer, right up to the end. I was starting to see why Godley was so upset.

‘There have been two acquittals in murder trials since he died, largely because he wasn’t there to defend his findings.’

‘And because his findings were shaky,’ Dr Early said. She glanced up at Godley, her face set. ‘He was a fine pathologist but he started making mistakes in the months before he died and he wouldn’t accept that his judgement was impaired.’

‘The pain medication affected him,’ Godley said. ‘He wanted to work – it was the only thing that mattered to him. But he needed to be dosed up to be able to do the job.’

‘He should have known better than to persevere. It was self-indulgent.’ It was professionalism that made Dr Early sound so severe. I knew she had done her utmost to help and support Dr Hanshaw, and that she had mourned him as a mentor, if not a friend. Glen Hanshaw had been a short-tempered misogynist and I’d never really understood Godley’s fondness for him.

Now the superintendent sighed. ‘Whether he should have been working or not, he’s become a target for defence lawyers. If he was involved in a case, you can expect the evidence he gathered to be challenged. And in the case of Leo Stone, the defence team are going to be looking for anything they can throw at the new jury to distract them from Stone’s guilt.’

‘The trouble with retrials,’ Derwent said, ‘is that they’ve heard all the best lines already. If you go back with exactly the same case and run it the same way, the defence know what to expect.’

‘Which is where you come in,’ Godley said. ‘I want to put a stop to the attacks on Glen’s reputation and his work. Dr Early has agreed to review his cases going back to before his diagnosis, and specifically his work on Leo Stone’s prosecution. In the meantime, I don’t want any cases to collapse purely because of his involvement. His reputation matters, and not just because he’s not here to defend himself. If all his decision-making is called into question we are going to see a torrent of appeals, especially from prisoners with whole-life tariffs.’

‘The worst of the worst,’ Una Burt said. ‘And they have nothing better to do than look for grounds to appeal. They’re in for life; they don’t have anything to lose.’

Godley turned to me. ‘Maeve, I want you and Josh to look at the case against Stone. Start from scratch: witnesses, families, the works. I’ll arrange a meeting with Paul Whitlock.’

‘He’s going to be pleased,’ Derwent observed. ‘Nothing like having another team come and take over your case.’

‘He’ll be professional about it,’ Godley said sharply. ‘He’ll understand why I don’t want to take any chances. Whitlock’s priority, and mine, is making sure that the right man is in prison for the murders of Sara Grey and Willa Howard. If that man is Leo Stone, I want him off the streets and behind bars.’

‘So don’t wind them up, Josh.’ Una Burt leaned all the way back in her chair, acting casual although her eyes were bright.

Derwent looked hurt. ‘Why single me out?’

‘Because I trust Maeve to behave herself.’ And I don’t trust you. She didn’t need to say it out loud. I suppressed a wince. Burt didn’t like Derwent, but I was the one who’d suffer for it.

‘Josh, I want you working on this case because I know you’ll do a good job. But Una is right. This is a high-profile investigation and you will be under scrutiny. It’s worth bearing that in mind from the start.’ There it was: the smooth diplomacy I’d missed so much from Godley. Derwent subsided, placated, and yet, from the satisfied expression on her face, Una Burt seemed to feel as if she’d won too. I had missed Godley more than I realised.

‘Can Georgia finish up on your case from last night?’ Burt asked me.

‘She should be able to handle it. We don’t have anyone in custody yet.’

‘I’ll get someone to take over as OIC.’ Burt squinted through the window that gave her a view of the office. ‘Chris Pettifer doesn’t look too busy.’

I didn’t want her to get someone else to take over – it was my case after all – but I knew that it was pointless to protest when DCI Burt had made up her mind. I made my face blank and nodded when Burt told me to brief Pettifer on the case before I went home.

‘You can take the files on the Stone case. Get your head around it before tomorrow.’

Or I could sleep, I thought, since I hadn’t for twenty-four hours. I could have a long bath and a decent meal and sleep.

‘Fine,’ I said.

Derwent stood up and stretched. ‘That’s useful. You do the reading, Kerrigan, and you can give me the highlights tomorrow.’

‘Why can’t you read up on it yourself?’ The question slipped out before I thought about whether it was appropriate for me, a detective sergeant, to ask a detective inspector why he wasn’t doing his job.

‘I’m busy,’ Derwent said coldly.

‘Right,’ I said under my breath, and bent down to pick up the box at my feet. Godley opened the door for me. Because I was tired and not really paying attention I started to move towards it at the precise moment when Derwent was walking past, and collided with him. I stepped back, horrified. He looked down at his shirtfront where a long black streak of mud had suddenly appeared on the immaculate white cotton.

‘Kerrigan.’

‘It was an accident,’ I said quickly.

He gave me the kind of look that he usually reserved for child-killers at the very least, and for a beat I held my breath. Then he lifted the box out of my hands as if it weighed nothing and walked away.

‘I can manage,’ I said to his retreating back, futilely.

‘Thank you, Maeve,’ Una Burt said from behind her desk, and I remembered where I was, and left her to her discussions with Godley and the pathologist.

4

Derwent was always a fast mover. By the time I made it out of Una Burt’s office, he was already on the other side of the room, well out of reach. He set the box down beside Pettifer’s desk with a remark that made the big DS throw his head back and laugh. I started towards them – it was still my case to hand over, I thought with a shiver of irritation – and checked myself as Georgia stepped into my path. She had found a hairbrush and cleaned herself up a bit. She’d managed to find the time to reapply her mascara, I noted.

‘What was that about?’ She nodded towards the office behind me. ‘Is that Superintendent Godley?’

‘Yeah.’ Of course Georgia would have spotted him. She had an extraordinary instinct for career advancement.

‘What’s he doing here?’

‘He had a job for me.’

‘Can I help?’

I raised my eyebrows. ‘You don’t even know what it is.’

‘So?’ Georgia’s blue eyes were unblinking. I could see it from her point of view: a chance to impress the boss before he came back to the team. Get a head start. Make progress.

‘I’m not in charge of this one.’

‘Who is? DI Derwent?’ She swung round, looking for him.

‘You’re going to be working with Pettifer on the Clarke case,’ I said firmly. ‘Once that’s out of the way, we might be able to use you. But at the moment—’

She pulled a face, obviously annoyed. ‘Pettifer can finish the Clarke case on his own.’

‘He could, but he isn’t going to.’ I stared her down for a long moment, daring her to take it further, and in the end she broke first.

‘So what’s the case?’

‘Reinvestigating—’ I broke off to cough. ‘Reinvestigating the Leo Stone case.’

‘The White Knight? Wow. I would love to work on that.’

‘Noted.’ There was nothing to encourage her in my tone of voice.

‘Why did Superintendent Godley want you to work on it?’ Her eyes were narrow.

Derwent leaned in between us. ‘Because he has a soft spot for Kerrigan.’ Georgia laughed.

‘Because he thinks I’ll do a good job,’ I said stiffly.

‘Of course you will.’ Derwent patted my arm.

Instead of arguing the point I walked away from both of them to talk to Pettifer myself. Georgia could try to convince Derwent to let her work on it too. If he wanted her, he’d include her in spite of my objections. If he didn’t want her help, nothing I could say would persuade him. Either way, I didn’t need to hang around.

He caught up with me in the kitchen where I was waiting for the kettle to boil.

‘What’s up with you?’

‘Nothing.’ I coughed again. Shit, I didn’t want to be ill. ‘I’m tired. I’m cold. I want to go home.’

‘My home.’

‘I’m renting it. That means it’s my home. Temporarily, anyway.’ I still wasn’t used to living in a space that I associated so completely with Derwent. For instance, I’d discovered there was no bleach strong enough to take away the mental image of him lounging in the bath.

‘As long as you’re looking after it.’

‘Yeah, I don’t want to piss off the landlord.’

‘Oh, you’ve done that already. Look at me.’

I did, reluctantly. He was holding the sides of his jacket open so I could see the muddy mark that ran across his chest. Not just the shirt: the tie too. ‘I said I was sorry.’

‘No, you said it was an accident.’

‘Well, it was.’ I took a deep breath. ‘But I’m sorry.’

‘Finally. You’re forgetting your manners.’

‘Speaking of which, I could manage the box by myself. You didn’t even ask before you took it.’

His eyebrows went up. ‘Don’t try to pretend that’s why you’re in a mood.’

‘I’m not in a mood.’ I turned and leaned against the kitchen counter, gripping it for courage. ‘I am very annoyed that you decided to stir up trouble by hinting that Godley wanted me to work on this case for any other reason than that he thinks I’m a good detective. You of all people know how unfair it is to suggest he puts professional opportunities my way for personal reasons.’

Derwent gave me his stoniest look. ‘That’s not what I did.’

‘Isn’t it?’

‘No.’

‘Saying he had a soft spot for me?’

‘It’s banter.’

‘It needs to stop. It’s not a joke. Someone like Georgia who doesn’t know any better will take it seriously, and I’ve had enough of it. You know it’s not true and you know there are a lot of people who’d like to believe that it is.’

‘You can’t live your life worrying about what other people think.’

‘Spoken like someone who doesn’t ever have to worry about it.’

‘You don’t have to. That’s my point. You’re choosing to care.’ He shrugged. ‘These people aren’t worth getting upset about. If they want to think the worst of you, they will, whether I say anything or not.’

‘Maybe, but you don’t have to throw fuel on the fire.’ Frustration was a knot in my stomach. It was impossible to explain how I felt to Derwent, and he didn’t have the imagination to put himself in my shoes. The gulf between his life and mine was unbridgeable. ‘You have no idea what it’s like to have to prove yourself over and over again,’ I said at last.

He rolled his eyes. ‘I have a fair idea.’

‘Because I’ve told you before. And yet, here we are, having the same conversation all over again.’ I turned away from him and squashed the teabag against the side of the mug, viciously. When I flicked the teabag at the bin I had the very small satisfaction that it went in first try.

‘I’ll keep it in mind,’ Derwent said at last. He almost sounded sincere. He would never admit he had been wrong, though, and nor would he apologise.

‘Thanks for being so understanding.’ I poured the milk into my tea and watched little white specks bob to the surface. ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, who puts gone-off milk back in the fridge?’

‘Poor Kerrigan. It’s not your day,’ Derwent said, and left, whistling as he went.

I leaned against the wall, defeated. I was tired and cold and fed up. All I’d wanted was a hot bath, a good meal and an early night. Instead I had nothing to look forward to but a long evening on my own, reading about someone else’s investigation and some very dead women. Not my day, not my week, not my year.

5

I had read the files and looked at the photographs until my eyes burned; I had watched the CCTV that the first investigation had painstakingly located and analysed. I knew the circumstances of Sara Grey’s disappearance inside out. Still, as Derwent drove down the Westway, I felt my pulse getting faster. Sara Grey. Victim one, chronologically.

‘Bloemfontein Road is coming up on the left. Not this one, the one after.’

Derwent slowed to make the turn.

‘This was where the tyre gave up.’

‘Puncture?’

I nodded. ‘They never worked out where she picked up the nail. There was nothing forensically interesting about it. Probably bad luck rather than Leo Stone’s planning. We have CCTV of her here, turning into Bloemfontein Road.’

‘Tell me about her.’

‘Sara Grey was twenty-nine at the time of her disappearance. She was engaged to Tom Mitchell, who was the same age as her. She was a primary school teacher; he had his own property development company.’

‘Did they ever check to see if he had employed Leo Stone?’

‘I didn’t see anything about it in the files.’ I scrawled a note to myself to look into it. ‘He was in Latvia on a stag weekend when it happened. Otherwise he’d have been suspect number one.’

‘Being out of the country doesn’t let him off the hook as far as I’m concerned. It’s a bit too convenient.’

‘Poor guy. If he’d been in the UK you’d be even more convinced he was involved.’

‘It’s always the husband. Or the fiancé. Or the boyfriend. Or the ex.’

‘Not this time. The original investigation focused on Tom, though, before her disappearance was linked to the others. They were looking for money worries or secret affairs or any kind of motive. They didn’t find anything.’

Derwent grunted, not convinced.

I leafed through my notes. ‘There was nothing to say Sara was being stalked – no concerns for her safety, no threats. On the day she disappeared no one was following her – at least as far as the investigators could determine.’

Derwent had slowed down to a crawl, creeping down Bloemfontein Road. ‘So what happened then?’

‘She parked just where that Volvo is. It was eleven at night but it was a Saturday, a summer night. There was a lot of traffic on the main road and there were people around. It was a warm evening – there’d been thunderstorms earlier but it was clearing up. When she got out of her car, she was seven hundred and eighty yards away from her home at 37 Haddaway Road.’

Today the light was flat, the clouds brooding over our heads. It was hard to imagine the street wrapped in the dark heat of a humid summer night.

Derwent pulled in a few cars ahead of the Volvo and parked. ‘Then what?’

‘Then she sent a text message to her fiancé telling him what had happened.’ I flipped to the relevant page and read it out. ‘Flat tyre!!! I don’t know what to do.’

‘The poor bloke was in Latvia. How was he supposed to come to the rescue?’

‘She probably just wanted to tell someone what had happened.’

‘No, she wanted to make him feel guilty for being off on a stag weekend instead of here.’

I raised my eyebrows at him. ‘That’s a very jaundiced view, even for you.’

‘She was high maintenance. I have limited patience for that.’

Melissa, Derwent’s girlfriend, was not the sort of person who would be low maintenance. If it had been anyone else I might have said as much, but Derwent had made it clear time and time again that while my personal life was endlessly entertaining, his was not available for discussion. Beside me, Derwent drummed his fingers on the steering wheel, as if he knew what I was thinking. ‘Then what happened?’

‘He replied: “Oh shit. Where r u? How bad is it? Driveable?” Obviously it wasn’t. She checked their AA membership and discovered it had lapsed so she decided to walk home. She sent him a message to that effect at 23.15.’ I showed Derwent the relevant page.

I can’t drive it. Left the car on Bloem Rd and I’m walking home. You can sort it out when you get back tomorrow.

Derwent grimaced. ‘Something for him to look forward to.’

‘He replied, “Typical! Call me when you get in.”’ I flipped the page. ‘According to this, “No further calls were made or received from Miss Grey’s phone and no further messages were sent by her. Mr Mitchell did not hear from his fiancée again after the message sent at 23.14. Cell site analysis revealed the phone remained switched on for a further twenty minutes, at which point it was powered down. Mr Mitchell informed police that it was highly unusual for Miss Grey to turn her phone off.”’

Derwent peered out of the car. ‘It looks like a safe enough area.’

‘It is. And they’d lived here for a year. She knew exactly where she was and she knew the quickest way home was going to be on foot.’

‘She should have been safe here.’ After a moment, he focused on me again. ‘So what route did she take?’

‘We don’t know.’ I pulled out a map I’d printed off. ‘This is Haddaway Road where she was heading. The direct route is along this road here, Haigh Road, leading into Radcliffe Road.’

‘Any reason to think she didn’t go that way?’

‘A bit of her mobile phone handset was found on Radcliffe Road in a hedge.’

‘OK. Sounds promising.’

I flattened the map out and pointed to a star I’d drawn. ‘It was here. Quite a long way from the path. I wonder if it was thrown out of a moving vehicle.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘This sighting of a couple arguing.’ I leafed through the file and pulled out the witness statement. ‘The witness was a Mrs Hamilton. She lives on Cordray Road, here.’ I showed him where it was on the map. ‘She was driving home and happened to glance along a side street in this area – she couldn’t be specific about which street it was but it was somewhere off Simpson Road.’

Simpson Road was about a quarter of a mile south of Haigh Road. ‘That’s way off the route she should have been taking,’ Derwent said.

‘Exactly. It was around the right time though. The investigators spent a lot of time trying to get Mrs Hamilton to remember anything else but she wasn’t a great witness, reading between the lines. She got more and more confused and in the end she said she couldn’t be sure of anything she’d told them. She withdrew her statement.’

Derwent groaned. ‘Good work, lads.’

‘It was a dark night, she was driving, she glanced down a side street and sort of saw two people who might have been arguing. It wasn’t going to make or break the case even if she remembered every detail.’

‘What did she say about the man?’

‘Nothing. He was standing behind a white van. She didn’t see more than the back of his head.’

‘Leo Stone’s pretty distinctive. He’s tall, for one thing. She’d have noticed that, surely.’

‘She said not. All she could say was that he was taller than the woman.’

‘How tall was Sara Grey?’

‘Five two.’

‘Right, so my nan would be taller than her.’

‘Yeah. It wasn’t altogether helpful testimony. Wrong place, right time, few details.’ I tapped my pen on the map. ‘The van, though.’

‘I like the van.’

‘We all like the van. It’s one of the only points of comparison we’ve got, apart from where the body ended up and how it was left, and that’s Dr Hanshaw’s territory.’ I didn’t need to say the rest because Derwent knew as well as I did that if that was called into question, we could lose Sara Grey altogether. The pathologist’s evidence was a big part of what had put Leo Stone behind bars. Without it, he could walk for good.

Derwent opened his door. ‘Let’s follow her route. Work out the timings. What time did Mrs Hamilton see the arguing couple?’

‘Half past eleven.’

‘So how long did she have to get there?’

‘Fifteen minutes or so.’

He looked me up and down. ‘Your legs are about twice as long as Sara Grey’s. You’ll have to take baby steps.’

Even with Derwent slowing me down (‘Oi, giraffe, put the brakes on’) it was possible to walk as far as Simpson Road in fifteen minutes. The area was middle-class, quiet, the houses well kept. It had been two and a half years since Sara Grey disappeared and there was no point in looking for evidence but I imagined her walking home, moving fast, her head down, and I wondered how she could have ended up so far off course. For once, Derwent was thinking the same as me.

‘Why would you go this way?’ He pulled the map out of my hand and studied it, frowning. ‘If we assume Mrs H was right about what she saw.’

‘These are busier roads than the direct route. Maybe she wanted to stay where there were more people around. Alternatively, something was making her uneasy. If someone was following her, she might have taken a different route home, trying to shake them off.’

‘Wouldn’t she have wanted to go straight home? Get indoors where she was safe?’

‘Not if she was concerned about them knowing where she lived. She’d never feel safe again if she led them to her door, even if she made it inside without coming to grief.’

Derwent shook his head and walked away.

‘What?’

‘Just …’ He swung back to face me. ‘What a way to live, that’s all. Working out what risks to take. Who to trust. Walking fifteen minutes out of your way to give yourself a better chance of making it home in one piece.’

‘That’s life, isn’t it? What’s the alternative? Staying at home?’

‘Maybe.’

‘You’re not serious.’ I folded my arms. ‘If anyone should stay at home, it’s men. They’re the ones who cause most of the trouble.’

‘Like that’s going to happen.’

‘Well, women shouldn’t have to hide away either.’

‘It’s for your own good.’

‘You have to live,’ I said quietly. ‘You look over your shoulder. You check who else is in your train carriage. It’s second nature – like looking both ways when you cross the road.’

‘I don’t always look both ways.’

‘I know.’ I had hauled him back onto the pavement out of harm’s way more than once. ‘I can’t decide if it’s male privilege in action or reckless stupidity.’

‘Bit of both.’

I started walking back towards the car. ‘Let’s assume for a minute that Leo is our killer. What was he doing here? He doesn’t seem to have any connection with the area. He didn’t grow up here. He never lived here. So why go hunting here?’